Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Harishchandragad

- Bhairavgadh

- Sant Dnyaneshwar's Dnyneshwari at Nevasa

- Medieval Period

- Ahmadnagar Sultanate

- Ahilyanagar City as the capital of Nizam Shahis

- Consolidation under Burhan and Hussain Nizam Shah

- Murtaza Nizam Shah I and the Expansion of State Power

- Marathas in the Court of the Nizam Shahis

- Maloji Raje Bhosale

- Shahaji Raje Bhosale

- Lakhuji Jadhav Rao

- Chand Bibi and Mughal Invasions

- Malik Ambar and the Revival of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate

- Shri Sai Baba of Shirdi

- Revenue System

- Local Resistance

- Marathas

- Battle of Kharda (1795)

- Colonial Period

- Annexation of Ahmednagar

- First War of Independence, 1857

- Local Libraries

- Female Educational Advancement

- Ahmednagar Sarvajanik Sabha

- Journalism

- Struggle for Independence

- The Quit India Movement, 1942

- Ahmednagar Fort as a Political Prison

- Post-Independence

- Technological Progress

- Cavalry Tank Museum

- Sources

AHILYANAGAR

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Ahilyanagar district is home to a rich and varied history that spans thousands of years. Many of its historical sites, though not always in the spotlight, provide valuable insights into the region’s connections with ancient civilizations and the cultural developments that have shaped it over time. Interestingly, the district has been inhabited since the Lower Paleolithic era, giving it roots that go back to prehistoric times. Over the centuries, it developed into an important hub for trade and administration, with ancient dynasties like the Satavahanas significantly influencing its cultural and political landscape.

Building on this long history, the district took on even greater significance in the 15th century when Malik Ahmad Nizam Shah I established it as the capital of the Nizam Shahi dynasty in 1494. The present-day city of Ahilyanagar became the political nucleus of the region during this period. One of the most prominent structures from this era is the Ahmednagar Fort, which later came under British control and was used to imprison several Indian nationalists, including Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and Jawaharlal Nehru. The district is also associated with several other figures linked to modern Indian history and politics. This extensive legacy, in many ways, reflects Ahilyanagar’s continued relevance across different periods of Indian history.

Etymology

In 1494, Malik Ahmad I, the founder of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, established a city on the left bank of the Sina River. In a rather personal touch, he named the city after himself, calling it Ahmednagar.

In 2024, the district was officially renamed Ahilyanagar in honor of Rani Ahilyabai Holkar of Indore, who is an influential figure in Maratha history, and one of the most admired women in Indian history. Born on 31 May 1725 in Chondi village within the district, Rani Ahilyabai became a prominent ruler of the Malwa Kingdom. In an era when it was uncommon for women to receive an education, she defied the norms and was taught by her father, a foundation that helped her rise to power and lead with great wisdom and vision.

Ancient Period

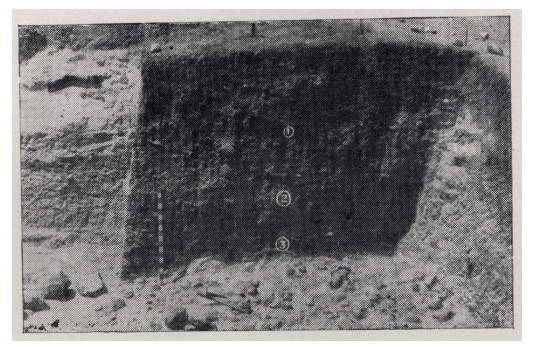

Ahilyanagar has a much older history than what is commonly known. Many sites connected to early human history and ancient civilizations have been uncovered and can be found in the region. One of these is the Chirki-Nevasa archaeological site, located about 3 km north of Nevasa town, which has revealed significant evidence of early human habitation. Excavations have uncovered Acheulian-era stone tools, such as handaxes and cleavers, dating back to the Lower Paleolithic period (approximately 6,00,000–3,00,000 years ago). According to archaeologists Z.D. Ansari, M.L.K. Murty, and R.S. Pappu (1976-77), these artifacts suggest early humans (hominins) lived in the region, utilizing resources from the Pravara River basin. The site's stratigraphy (layer analysis of soil) shows that these tools were recovered from the basal rubble gravel layer (lowest deposit of coarse stones), suggesting they are of considerable antiquity.

The Pravara River basin has also revealed evidence of later ancient settlements. Near Daimabad, on the river’s left bank, remains linked to the Late Harappan phase of the Indus Valley Civilization have been uncovered. These findings indicate that the cultural reach of the Indus Valley extended into the Deccan Plateau, connecting the district to broader ancient cultural networks.

As time progressed, this region witnessed the development of settled agricultural societies. The Daimabad site, further downstream along the Pravara River, marks this transition. Here, archaeologists identified a cultural sequence that spans the Salvada culture, the Late Harappan phase, and several regional ceramic traditions including Malwa, Buff and Cream Ware, and Jorwe. These communities, active from roughly 2300 to 700 BCE, built permanent homes, practiced farming, and created distinct pottery, showing increasing social organization and technological skill.

Daimabad drew national attention in 1974 with the discovery of four bronze sculptures: a bull-drawn chariot carrying a human figure, along with separate depictions of an elephant, rhinoceros, and buffalo. This remarkable find sparked renewed excavations, which revealed seals and pottery marked with signs resembling those of the Indus Valley Civilization. While located well beyond the Harappan core area, Daimabad’s material culture suggests contact—whether through trade, migration, or shared symbolic systems—between the Deccan and northwestern South Asia.

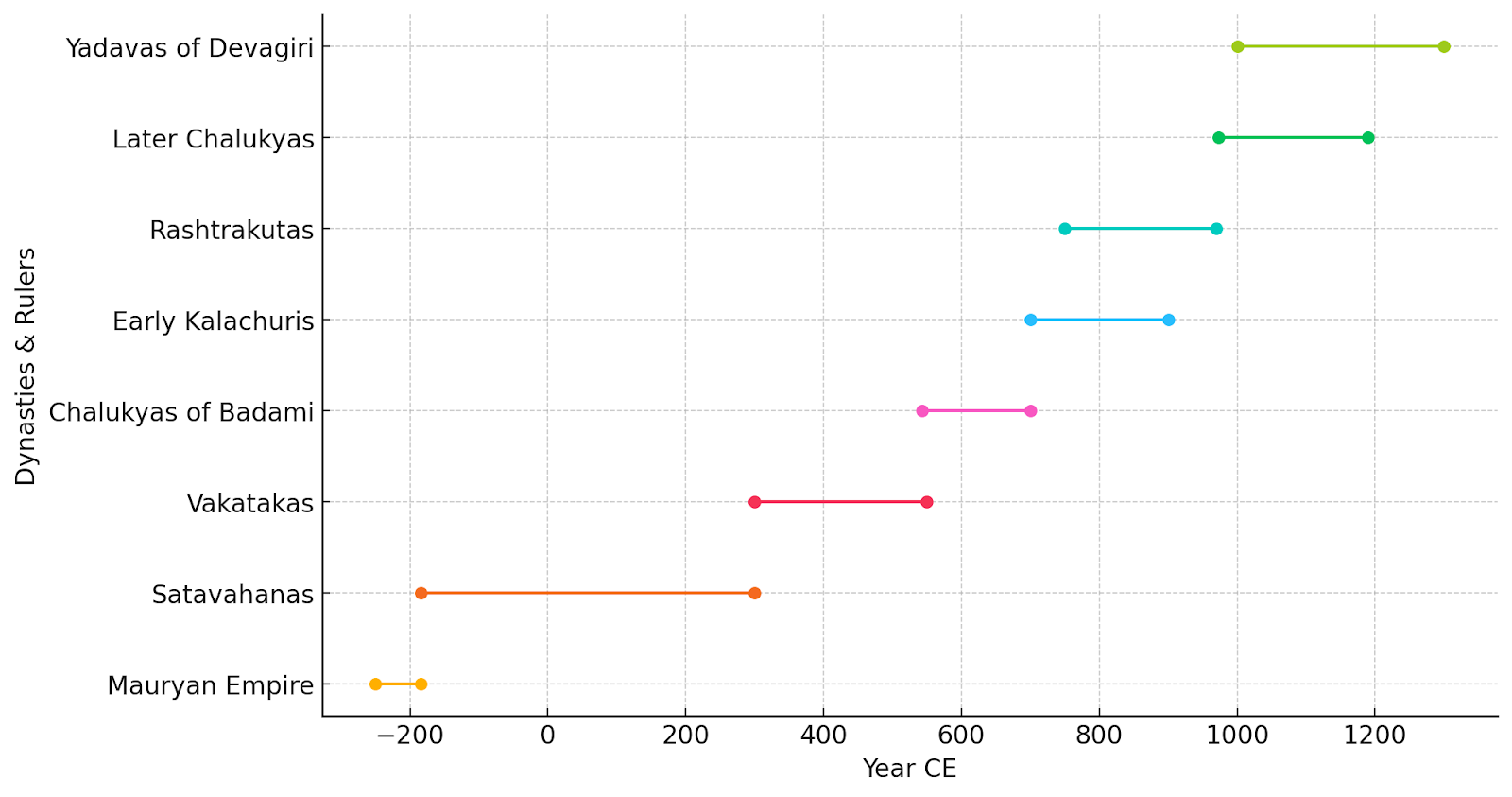

Together, Chirki-Nevasa and Daimabad provide a rich picture of human history in the Ahilyanagar region. Later, Diverse dynasties and rulers have also shaped the history of the district over the centuries. The district was historically part of key ancient dynasties, including the Mauryan, Satavahana, and post-Mauryan empires.

According to the district Gazetteer (1976), Buddhism likely reached the Ahilyanagar region during the Mauryan period, as suggested by Ashokan edicts found at Sopara (Palghar district) and Deotek (Chandrapur district). These inscriptions indicate the extent of Ashoka’s influence in Maharashtra. The Mahavamsa, a Buddhist chronicle, further records that the missionary Dharmarakshita was sent by Ashoka to this region.

The Satavahanas, who succeeded the Mauryas around 184 BCE, ruled much of Deccan, including Ahilyanagar District. Gautamiputra Satakarni recovered Western Maharashtra (including Ahilyanagar) from the Kshatrapas, as recorded in the Nashik Prashasti (inscription of his mother Gautami Balashri). The Satavahana kingdom included Rishika (present-day Khandesh), Ashmaka (covering present-day Ahilyanagar and Beed districts), and Mulaka (present-day Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar district). Excavations at Nevasa unearthed Satavahana coins and inscriptions. The Dhodeshwar caves in the district dates back to this period, showing the influence of Buddhist rock-cut architecture. With their capital at Pratishthana (Paithan), just north of the present district boundary, the Satavahanas likely governed the Ahilyanagar region between the 1st century BCE and 3rd century CE as part of their wider Deccan dominion.

From around 4th – 5th Century CE, the district was possibly under the rule of Vakatakas. The Pandarangapalli plates of Adividya, a Vakataka ruler, mention their conflicts with Rashtrakutas over Vidarbha and Ashmaka (Ahilyanagar). Ajanta Caves, excavated during the Vakataka period, show their patronage in Maharashtra, and the Ahilyanagar region is believed to have been influenced by their rule.

During the 6th and 7th centuries CE, the Ahilyanagar region witnessed a power transition from the Vakatakas to the Chalukyas of Badami and later the Rashtrakutas.

In the mid-6th century, the Vakatakas, who controlled much of Vidarbha and northern Maharashtra, started to decline around 550 CE. Their last known ruler, Harishena, expanded the kingdom, but soon after his death, the empire fragmented. The Ahilyanagar region, which was part of Ashmaka, likely came under local feudatories for a brief period.

The Chalukyas of Badami (present Karnataka region) took control from 6th to 7th Century CE. Pulakeshin I (543–566 CE) established the Chalukya dynasty at Badami. His successor, Kirtivarman I (566–597 CE), defeated the remnants of the Vakatakas and expanded Chalukya rule into Maharashtra, likely including Ahilyanagar. Pulakeshin II (610–642 CE), the greatest Chalukya ruler, extended his power further north, defeating Harsha of Kannauj. His victory against the Kalachuris of Mahishmati secured western Maharashtra, including Ahilyanagar. The Kalachuris of Mahishmati (also known as the Early Kalachuris) were based in present-day Madhya Pradesh and governed large parts of present-day Gujarat, and Maharashtra during the period likely around the 8th - 9th centuries. However, Pulakeshin II was eventually defeated and killed by the Pallavas in 642 CE, which weakened the Chalukyas considerably.

Around mid-7th century CE, the Rashtrakutas, initially feudatories of the Chalukyas, started gaining power. Subsequently, Dantidurga, the founder of Rashtrakuta power and his successors controlled Karnataka, Gujarat, and Maharashtra, including Ahilyanagar from 8th – 10th Century CE. Copperplate inscriptions from Sambhajinagar and Nashik suggest Rashtrakuta rule in the surrounding areas.

Later the Yadavas (spanning the 10th to 13th centuries CE) established their rule under Bhillama V, a Yadava king who founded the capital at Devagiri (modern Daulatabad), located near present-day Ahilyanagar. According to the district Gazetteer (1976), places such as Kalasa and Sangamner are mentioned in grants issued by Bhillama II around 1000 CE. Further evidence of Yadava administration is found in the Kalas Budruk plates dated to 1025 CE, discovered in Ahilyanagar. It is noted in the Gazetteer that “on the rise of the Later Chalukyas, Bhillama transferred his allegiance to them. The next king was Vesugi, who married a Shilahara princess, the daughter of Goh, the successor of Jhanjha, ruling over north Konkan. His son was Bhillama II, whose Kalas Budruk plates dated in Shaka 948 (BCE 1025) were found in the Kaloa taluka of Ahmednagar district.”

Harishchandragad

Many historical sites that are believed by many to be ancient in the district. Among the more prominent historical sites in the region is the hill-fort of Harishchandragad, situated in the rugged terrain of the Malshej Ghat. The fort is believed to date from the early medieval period, with architectural and sculptural features suggestive of construction during the 8th or 9th century CE.

While definitive records of its origin remain scarce, the site is frequently associated by scholars with the Kalachuris of Mahishmati, a dynasty whose political influence, though centred in the Narmada valley, is thought to have extended into parts of western Maharashtra during their ascendancy. The Kalachuris, however, did not maintain lasting control over the region; their decline coincided with the expansion of the Chalukyas of Badami, whose dominion eventually encompassed much of the Deccan.

Throughout the fort, numerous caves are scattered, adding to its historical significance. The surrounding caves within the fort complex are believed to have been carved out around the 11th century under Yadava Rajas. The caves housed the Mandir of Bhagwan Vishnu. The architectural layout resembles a citadel and multiple fort complexes.

In the cave complex, Harishchandreshwar Mandir is another important religious site. It is dedicated to Harishchandreshwar (Bhagwan Shiv), and it showcases the Hemadpanthi style of architecture unique to Yadavas. It is characterized by the use of black stone and lime without mortar, employing the technique of mortise and tenon joints. This Mandir has been painstakingly carved out of a single massive rock. It stands as a magnificent example of the 12th century Yadava dynasty's art of stone sculpting.

It is popularly believed that in the 14th century, the revered Sant Changdev Maharaj (see Jalgaon for more), journeyed to this location for meditation.

Saptatirtha Pushkarni is a meticulously constructed lake situated east of the Harishchandreshwar Mandir. It is believed that, adjacent to the lake, there was once a mandir-like structure containing a pratima of Bhagwan Vishnu, which has since been relocated to the caves.

Nearby, lies the Kedareshwar Mandir. While its exact origin remains unknown, it is speculated to be another ancient relic in the district. This cave houses a five ft. tall Shivling positioned amidst ice-cold water. The water level reaches approximately waist-high, making access to the Shivling. Intricate sculptures adorn the cave, adding to its allure. It is popularly seen that during the monsoon season, accessing the cave becomes even more difficult due to a substantial stream obstructing the path. Additionally, an intriguing aspect is the daily seepage of water through the mandir’s four walls.

Before the Mughals assumed control of the region, including Harishchandragad, it is widely believed that the fort was likely managed by the Koli community. The carvings of Nageshwar within the Mandir, and in the cave of Kedareshwar are believed to be associated with the Mahadev Koli community. Eventually, the fort fell under Mughal control until it was brought under Marathas in 1747.

Bhairavgadh

Bhairavgadh is perhaps built during ancient period as well. Although it’s not conclusive who built it, it is a significant historical site in the district and is known for its architectural marvel and strategic significance. It has two big caves, one of which hosts a small Mandir of Bhairavnath, and another which was used as a residence. The broken steps found on the fort are thought to be the aftermath of a historical conflict or event that resulted in its partial destruction. It is widely believed that these damaged steps were likely caused by actions undertaken by the British during their occupation of the fort. The fort is accessible from Shirpunje village and Ambit village and is part of the Kalsubai-Harishchandragad Wildlife Sanctuary currently.

Sant Dnyaneshwar's Dnyneshwari at Nevasa

Sant Dnyaneshwar wrote the Dnyaneshwari at a place called Nevasa, in Ahliyanagar District, around 1290 CE. The scripture was composed by Sant Dnyaneshwar, while he was seated next to a pole that still exists today at this location, which is sometimes called the "Pais Khamb". The place is also known as Pravara Sangam because the river Pravara flows into the Godavari at this particular place.

Medieval Period

From 1318, Maharashtra was governed by Delhi-appointed governors stationed at Devagiri (present Daulatabad), and in 1338, Muhammad bin Tughluq made Devagiri his capital, renaming it to Daulatabad.

In 1351, Alauddin Hasan Gangu Bahmani, claiming independence from Delhi Sultanate, unified the Deccan region under his rule. According to the district Gazetteer (1884), his approach was characterized by a liberal and friendly approach towards local chiefs and authorities. As a result, he successfully brought all parts of the Deccan that were previously under the rule of the Delhi Sultanate, under his control.

During this period, the Koli community of the western Ahilyanagar hills gained a significant level of independence. In 1346, one of them, Papera Koli, was appointed as the chief of Jawhar area in the North Konkan (see Palghar district for more on Jawhar) by the Bahmani king. According to the Gazetteer, the Jawhar territories initially included a substantial portion of the district, comprising 22 forts and generating a yearly revenue of £90,000 then. The Bahmani kings allowed the Kolis to remain largely independent under their own chiefs as long as they maintained peace.

The western Ahilyanagar and Pune regions were divided into 52 valleys, each under a hereditary Koli chief with the rank of a noble in the Bahmani kingdom. The head of the valleys, Sar Naik, was a Muslim based in Junnar (in present-day Pune city). In 1357, Alauddin Hasan Gangu Bahmani divided his kingdom into four provinces, with Ahilyanagar under the charge of the king's nephew.

The administrative structure that prevailed under the Bahmanis in this region remained intact for several decades and would form the institutional and territorial framework upon which the Ahmadnagar Sultanate later emerged.

Ahmadnagar Sultanate

The establishment of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate in the closing decade of the fifteenth century marked one of several emergent Deccan powers arising from the disintegration of the Bahmani Confederacy. Malik Ahmad, a former noble in the Bahmani court and the son of Malik Hasan Bahri—a Brahmin convert who had risen to the title of Nizam-ul-Mulk—declared independence in 1490, assuming the title of Ahmad Nizam Shah I. The new state was founded in a period of considerable instability, and its early shape was defined as much by opportunism as by deliberate statecraft.

At this time, Malik Ahmad had already secured the confidence of the Bahmani Sultan Mahmood Shah Bahmani II, having served as Malik Naib and, briefly, as Prime Minister. His early governance over the region corresponding to the present-day Beed and Daulatabad districts provided a base for expansion, and once independence was declared, he first established his capital at Junnar.

Ahilyanagar City as the capital of Nizam Shahis

However, in 1494, he moved his seat to a newly founded city on the left bank of the Sina River. According to the Gazetteer (1884), within two years of its establishment, the city is said to have matched the grandeur of Baghdad and Cairo in magnificence. It was from here that the Nizam Shahis ruled their kingdom and the city served as a capital, making the present-day district a major center for this dynasty.

The selection of the site was determined by its proximity to the established trade routes of the western Deccan, as well as its defensibility. Soon after establishing the city, Malik Ahmad undertook the construction of the Ahmadnagar Fort, which was to serve as the principal military outpost of the state.

In addition to this Ahmad Nizam Shah I secured control over the strategically vital fortress of Daulatabad in 1499. This act not only confirmed the military viability of the fledgling sultanate but also placed it in direct contention with its neighbours—particularly the Sultanates of Bijapur and Berar—who viewed the consolidation of Ahmadnagar with growing concern. Malik Ahmad’s reign thus laid the architectural and administrative foundation for a dynasty that would endure, albeit in varied form, for nearly a century and a half.

Chronology of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate (1490–1636)

- Malik Ahmad Nizam Shah I (1490–1510)

- Burhan Nizam Shah I (1510–1553)

- Hussain Nizam Shah I (1553–1565)

- Murtaza Nizam Shah I (1565–1588)

- Burhan Nizam Shah II (1591–1595)

- Ibrahim Nizam Shah (1595–1596)

- Ahmad Nizam Shah II (1596–1600)

- Chand Bibi (Regent) (1596–1599)

- Murtaza Nizam Shah II (1600–1610)

- Burhan Nizam Shah III (1610–1631)

- Hussain Nizam Shah III (1631–1633)

- Murtaza Nizam Shah III (1633–1636)

Annexed by the Mughal Empire in 1636.

Consolidation under Burhan and Hussain Nizam Shah

On the death of Ahmad Nizam Shah I in 1510, the throne passed to his seven-year-old son, Burhan Nizam Shah I. During the early years of his reign, actual authority was exercised by Mukammal Khan, a trusted officer, and his son. The regency continued until the young Sultan attained majority, by which time the central institutions of the sultanate had taken a more stable form. Burhan Nizam Shah’s reign is particularly notable for the formal adoption of Shi‘a Islam as the state creed, following his instruction under the renowned religious teacher Shah Tahir Husaini. This shift would prove consequential, setting Ahmadnagar apart in its sectarian alignment within the Deccan and further distinguishing it from its Sunni neighbours.

Burhan’s rule extended over four decades, during which the sultanate navigated both internal consolidation and external threats. By the time of his death in 1553, the dynasty had matured into a durable polity, although the seeds of future instability had already begun to be sown. His son, Hussain Nizam Shah I, succeeded him and reigned until 1565. Hussain continued the administrative and religious policies of his predecessors. His reign concluded on the eve of a new phase in Deccan politics, heralded by the rise of a capable and ambitious heir.

Murtaza Nizam Shah I and the Expansion of State Power

The accession of Murtaza Nizam Shah I in 1565 introduced a period of remarkable administrative expansion and cultural consolidation. Being a minor at the time of his father’s death, the affairs of state were managed under the regency of his mother, Khanzada Humayun Sultana, whose role, though often overlooked, was critical in preserving the autonomy of the sultanate during the early years of his reign. When Murtaza came of age in 1572, he quickly moved to assert his authority. One of his first major undertakings was the annexation of Berar, a feat that extended Ahmadnagar's northern frontier and brought it into direct alignment with Mughal interests in Khandesh.

At this time, considerable resources were also directed toward architectural projects intended to symbolise dynastic prestige. Chief among these was the construction of the Farah Bagh palace at Morchudnagar. Begun in 1576 and completed by 1583, the palace adhered to a Persianate architectural grammar: a domed central hall rose from an octagonal plinth and was encircled by a three-storey verandah. Its name, Farah Baksh, meaning "joy-bestowing," reflected its intended function as a garden-retreat for the sovereign.

There is an interesting anecdote behind the creation of Farah Baksh Bagh. Early in his reign, Nizam Shah assigned Niamat Khan Simnani to oversee the creation of a magnificent garden-resort. Sayyid Ali Tabatabai (A Persian chronicler, who wrote about Bahmani Sultanate), in his work Burhan-i Masir records that,

"At this time, Niamat Khan Simnani, who had been raised from the corner of humility to the summit of honour, was ordered to lay out a garden and dig a water-course. In a short time, he laid out a splendid garden and built in it a fine palace."

Yet, upon visiting the site, the Sultan expressed dissatisfaction with the design. As Muhammad Qasim Firishta records:

"When Murtaza Nizam Shah went to that garden for amusement, it did not appeal to him. He at once dismissed Niamat Khan from the superintendence of that garden, and instructed Salabat Khan to pull down the building (on which immense money had been spent), and construct another in its place."

The reasons for this drastic reversal appear not to have been purely aesthetic. Astrological beliefs of the time held that edifices erected under the influence of Mars were inauspicious, associated with conflict and disorder. In light of the Sultanate's strained relations with its neighbours, Murtaza is believed to have opted for demolition despite the expense.

Later tradition holds that Shah Jahan, during a period of political exile, may have drawn inspiration from the aesthetic principles of Farah Bagh in the eventual construction of the Taj Mahal. Though now much weathered, its presence stood as a testament to the sultanate’s sophistication in court architecture and its visual aspirations of grandeur.

Marathas in the Court of the Nizam Shahis

The latter half of the sixteenth century also witnessed the increasing presence of Maratha chiefs in the court and military of Ahmadnagar, which many scholars notably believed to be a distinctive trend in the Deccan region. Of these, the most prominent were Maloji Bhosale and Lakhuji Jadhav Rao, both of whom held important commands and were granted substantial jagirs including Pune, Supe, Chakan, and Shivneri. Maloji Bhosale of Verul and Lakhuji Jadhav Rao of Sindkhed emerged as the most notable Maratha commanders in Ahmadnagar. Both men were entrusted with substantial jagirs, including Pune, Supe, Chakan, and the strategic fort of Shivneri. Notably, historian Sam Dalrymple (2025) observes, “Ahmadnagar embraced Marathi cultural and administrative traditions, integrating local chieftains (Marathas) into governance and military structures.”

This integration was visible not only in personnel but also in the arts. Architectural forms of the period, such as the rectangular framing of arches in Nizam Shahi tombs, borrowed from local temple design, producing what later scholars have called “proto-Maratha” architecture.

In language, too, Persian court idioms were gradually supplemented by Marathi usage in administrative contexts, creating a syncretic style that anticipated the cultural complexion of the early Maratha state under Shivaji.

Maloji Raje Bhosale

Long before the rise of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj (see Pune district for more), the Bhosale family’s ascent began with his grandfather, Maloji. An ambitious Maratha noble, Maloji rose to prominence in the late 16th century through his service in the Ahmadnagar Sultanate.

Maloji was born in 1552 in Verul (now Ellora), a village near the Ellora Caves in present-day Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar district, Maloji belonged to the Bhosale clan, a Maratha lineage that gradually advanced in status through service in the Deccan sultanates and would later play a significant role in regional politics.

According to Balkrishna (1932), Maloji initially served under the Jadhav family of Sindkhed, military retainers of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate. His growing reputation, along with that of his brother Vithoji, led to their direct enlistment by the Nizam Shahi ruler in campaigns against the Bijapur Sultanate. Their success in these engagements earned them recognition and they were rewarded with the jagirs of Pune and Supe along with forts of Shivneri and Chakan. Under Nizam Bahadur Shah (1595-1600) (the 8th Nizam), he was given the prestigious title of Raja.

Shahaji Raje Bhosale

After Maloji’s passing, the jagir was passed onto his son Shahaji, the father of Shivaji. Shahaji, served as a junior commander in Malik Ambar's army. According to Oturkar (1956), by 1625, Shahaji had risen to the prestigious rank of Sar Lashkar (major general). Shahaji became a vital figure in defending the Sultanate against the relentless advance of the Mughal Empire in the early 17th century. However, as the tides of power shifted and the Ahmadnagar Sultanate fell in 1636, Shahaji pragmatically aligned himself with the Bijapur Sultanate to continue his political and military career. Post-1636, after the fall of Ahmednagar Sultanate, Shahaji entered the service of the Bijapur Sultanate (one of the Deccan Sultanates), continuing his military career until his death in 1664.

Shivaji later rose to prominence by establishing the Maratha Empire, perhaps inspired in part by his father's legacy and experience in Deccan politics.

Lakhuji Jadhav Rao

The Jadhav Rao family of Sindkhed Raja (present-day Buldhana district) was another pillar of Nizam Shahi military strength. Lakhuji Jadhav Rao, known for his boldness in the field, was father-in-law to Shahaji and thus grandfather to Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. The Buldhana District Gazetteer (1976) records his reputation for military innovation, including tactics that some scholars believe influenced early Maratha guerrilla warfare.

Lakhuji’s career saw significant victories, including the capture of Daulatabad Fort and success in the Khandesh War, earning him the title “Maharao of Khandesh.” His position brought him a mansab (rank) of 10,000 under the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, later raised to 24,000 by Mughal Emperor Jahangir in 1621 as part of a political alliance. However, his rising influence provoked the suspicion of Burhan Nizam Shah III, who had Lakhuji and his family executed at Daulatabad Fort in 1629.

Chand Bibi and Mughal Invasions

The increasing involvement of Maratha chiefs in Ahmadnagar’s service would, in the years ahead, be marked by frequent shifts in allegiance, a trend which is rooted in a pivotal moment during the Mughal advance at the close of the sixteenth century. The last years of the sixteenth century brought Ahmadnagar into sustained conflict with the Mughal Empire. In 1595, following the death of Sultan Murtaza Nizam Shah II, the regency fell to Chand Bibi (also known as Chand Sultana), daughter of Hussain Nizam Shah I and great-granddaughter of the dynasty’s founder. Acting on behalf of her minor nephew, Bahadur Shah, she faced an immediate threat from a Mughal army commanded by Khan-i-Khanan Abdur Rahim and Prince Daniyal.

The siege of Ahmadnagar Fort that followed became the episode for which Chand Bibi is chiefly remembered. Outnumbered and short of supplies, she nonetheless organised a defence that held for several months, forcing the Mughals to negotiate. The resulting treaty ceded Berar to the Empire but left Ahmadnagar otherwise intact—a temporary safeguard of its independence.

In 1599, amid renewed hostilities, Chand Bibi was killed, it is said by her own retainers, who suspected her of intending to surrender. Her death removed one of the most capable figures in the Deccan resistance to Mughal expansion, and she remains emblematic of the region’s opposition to imperial absorption.

Malik Ambar and the Revival of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate

Following the death of Chand Bibi in 1599 and the Mughal capture of Ahmadnagar Fort, the Nizam Shahi dynasty seemed on the brink of collapse. Yet the sultanate endured for another quarter-century under the leadership of Malik Ambar (1600–1626), an Ethiopian-born former slave who rose to be regent to the young Sultan Murtaza Nizam Shah II.

From his new capitals—first Paranda, then Junnar, and finally Khadki (later Aurangabad)—Malik Ambar rebuilt the state’s authority. He expanded the cavalry from a mere 150 to 7,000 within a short span, eventually commanding a force of 10,000 Habshis (Abyssinians) and 40,000 Deccanis. By appointing pliant sultans, he retained real power while maintaining the legitimacy of the dynasty, and used these resources to repel repeated Mughal invasions.

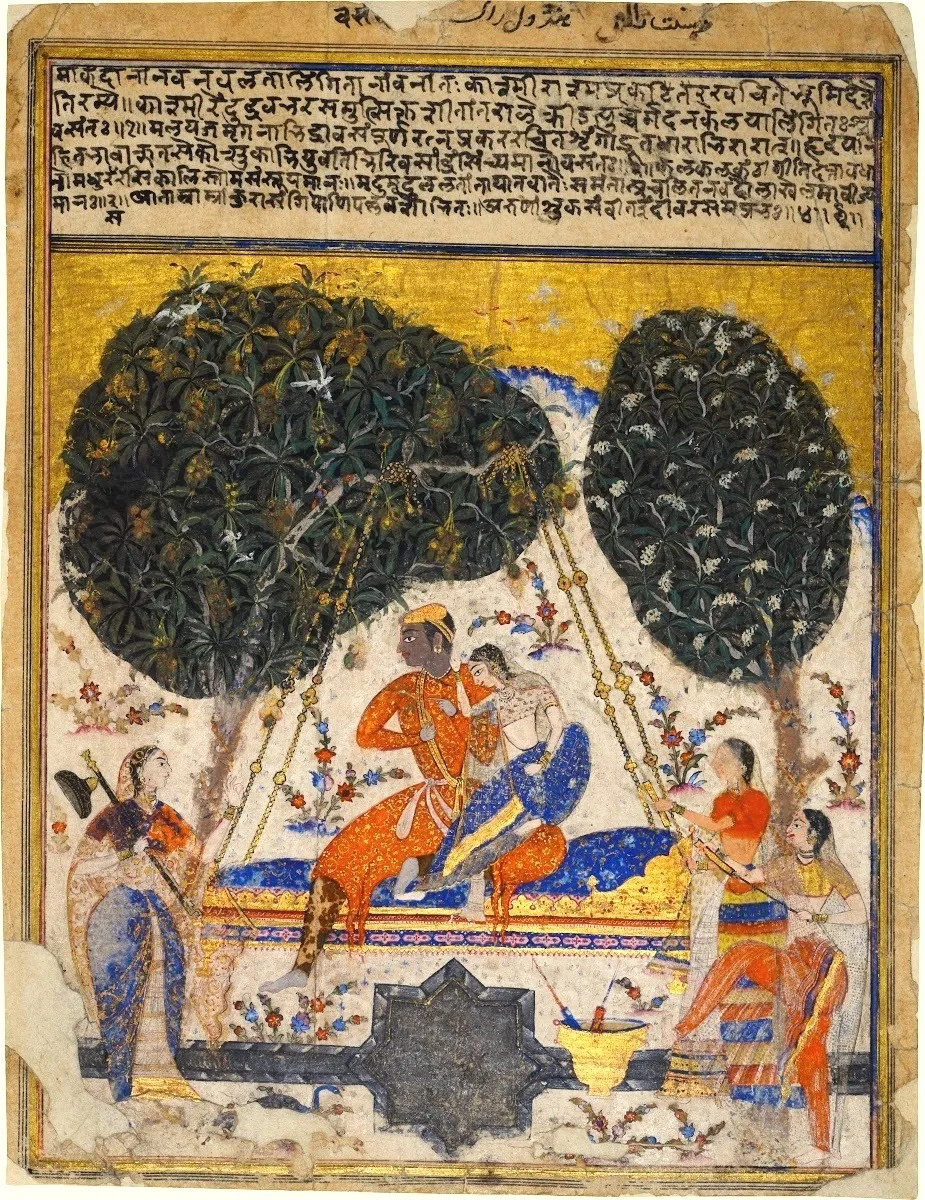

A master of guerrilla tactics, Malik Ambar repeatedly frustrated Emperor Jahangir’s armies, earning the Emperor’s deep enmity. Jahangir referred to him in court records as “ill-starred” and “black-fated,” and even commissioned a painting by court artist Abu’l Hasan in 1615 showing himself firing arrows at Ambar’s severed head. Despite such animosity, Malik Ambar proved resilient. By 1610, he had restored much of the lost territory and reputation of the Ahmadnagar state.

Shri Sai Baba of Shirdi

Shirdi Sai Baba was an Indian spiritual master widely revered as a saint by both Hindu and Muslim devotees during his lifetime and beyond. His teachings centered on the realization of the self and the rejection of attachment to material and transient things. Sai Baba advocated for a moral and spiritual code founded on love, forgiveness, compassion, charity, contentment, inner peace, and devotion to both God and Guru. He firmly opposed discrimination based on religion or caste and maintained an inclusive approach that transcended sectarian boundaries.

Sai Baba’s philosophy seamlessly integrated elements of Hinduism and Islam. He named the mosque in which he resided Dwarakamayi, performed rituals from both faiths, and conveyed his teachings through symbols and expressions drawn from both religious traditions. According to the Shri Sai Satcharita, many of his Hindu followers regarded him as a divine incarnation (Purna Avatar) of the deity Dattatreya.

Revenue System

He is also known to have introduced significant reforms to the district's revenue policy. Resisting the Mughal incursions, he successfully held the Sultanate for a period. One of the key transformations during his rule was the adoption of Akbar's renowned revenue system, implemented by his influential finance minister, Raja Todar Mal. This system, inspired by Raja Todarmal's reforms in Northern India and parts of Gujarat and Khandesh subahs, categorized lands based on their fertility. It took several years to accurately assess the average yield of these lands.

According to the Gazetteer (1884), under this system, revenue farming was abolished, and initially, the revenue was fixed at two-fifths of the actual produce in kind. However, later on, cultivators were allowed to pay in cash, approximately equivalent to one-third of the yield. Although an average rent was established for each plot of land, the actual collections varied based on crop conditions and fluctuated from year to year.

Another significant Mughal reform introduced in the Deccan was the implementation of the Fasli, or harvest year. Instituted by Akbar during his reign (1556-1605), the fasli, based on the solar calendar, commenced with the onset of the southwest monsoon in early June. However, as there was no effort made to synchronize the fasli with the lunar Mohammadan year, it gradually deviated from the traditional lunar year by more than three years every century.

Local Resistance

The implementation of this new system faced resistance from the Kolis of West Ahmednagar. They found the measurement of lands and establishment of rents under this new system to be burdensome. The Gazetteer (1884) records that the leader, Kheni, rallied the chiefs to pledge to revolt at the first opportunity against Mughal rule. The ensuing uprising was met with harsh reprisals, including the execution of the Koli leader's family. These events further affected the relationship between the Koli community and the Mughals.

By the early 17th century, the Ahmadnagar Sultanate fell to the Mughals. The decline of the Sultanate created a power vacuum in the Deccan, leading the Maratha Empire under Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj to rise in the mid-17th century.

Marathas

In the 1660s, Shivaji conducted military activities , particularly targeting areas under Mughal control in Ahilyanagar. According to the Gazetteer (1884), during the rainy season of 1662, under the guidance of Moropant, Shivaji's minister or Peshwa, Shivaji's infantry seized several strongholds north of Junnar (present Pune). As soon as the land dried up, his cavalry, led by Netaji Palkar, pillaged the Mughal districts. Netaji was tasked with looting villages and extorting contributions from towns. However, he went beyond these orders, occupying the countryside near Aurangabad (Sambhaji Nagar), moving swiftly from place to place. In response to this military advancement, Shaista Khan, appointed as the viceroy succeeding Prince Muazzam, was ordered to punish Shivaji's forces. He led a large force from Sambhajinagar, taking the route via Ahilyanagar and Podgaon to Poona.

In 1663, while Shaista Khan was in Pune, Netaji Palkar was conducting raids near the district. Netaji and his men were intercepted by Shaista Khan. Despite being wounded, Netaji narrowly escaped capture, thanks to Rustum Zaman, the Bijapur general, who facilitated his evasion. During the rainy seasons of 1664 and 1665, Netaji continued to advance inland with great success. In August 1665, it is said that Shivaji himself advanced towards the town of the district.

The eighteenth century was marked by a more complex struggle, with the Nizam of Hyderabad emerging as the principal rival to Maratha power in the Deccan. In 1759, the Nizam’s commandant Kavi Jang surrendered the fort of Ahmadnagar to the Peshwa, precipitating war. The Marathas captured Pedgaon Fort on the Bhima River and in 1760 won a decisive victory over the Nizam at Udgir (see Latur district), compelling him to cede Ahilyanagar, Daulatabad, and other territories.

The setback of the Third Battle of Panipat in 1761 enabled the Nizam to counterattack, burning the temple at Toka, where the Pravara meets the Godavari, and marching towards Pune. The Peshwa was forced to restore some of the districts lost in 1760, though the Marathas retained most of Ahilyanagar.

By the 1790s, instability within the Maratha Confederacy created opportunities for ambitious leaders. In 1796, Daulat Rao Scindia of Gwalior secured control of Ahmadnagar Fort and its surrounding lands, using them as a base for his faction’s influence in the Deccan.

Battle of Kharda (1795)

The closing years of the eighteenth century witnessed one of the last combined operations of the Maratha Confederacy against the Nizam of Hyderabad. In early 1795, disputes arose when the Nizam refused to pay the chauth demanded by the Peshwa. The Maratha forces, led by Sawai Madhavrao Peshwa, advanced into Nizam territory. On 11 March 1795, near the village of Kharda in present-day Ahilyanagar district, the two armies met in battle.

The Maratha victory was decisive. The Nizam’s forces were outmanoeuvred, and his lines broken after sustained cavalry and artillery assaults. The subsequent treaty imposed a large indemnity, estimated at thirty million rupees, and required the cession of territory, including a share of the revenues from Berar to the Nagpur Bhosales.

Contemporary records mention the participation of several notable commanders: Sardar Mansing Khalate (Nikam), Sardar Maloji Ghorpade of Mudhol with his grandson Narayanrao Ghorpade, the Dagars under Sonusingh Bias, cavalry leaders Naik Ramchandra Bhosale and Borkhedkar, and artillery under Yesaji Waibhat. Their combined efforts ensured a swift conclusion to the campaign.

Although Kharda confirmed Maratha supremacy over the Nizam, it also proved to be the last occasion when the Confederacy acted in unity. In the years that followed, internal rivalries and the growing influence of the British East India Company would steadily erode Maratha authority in the Deccan.

Colonial Period

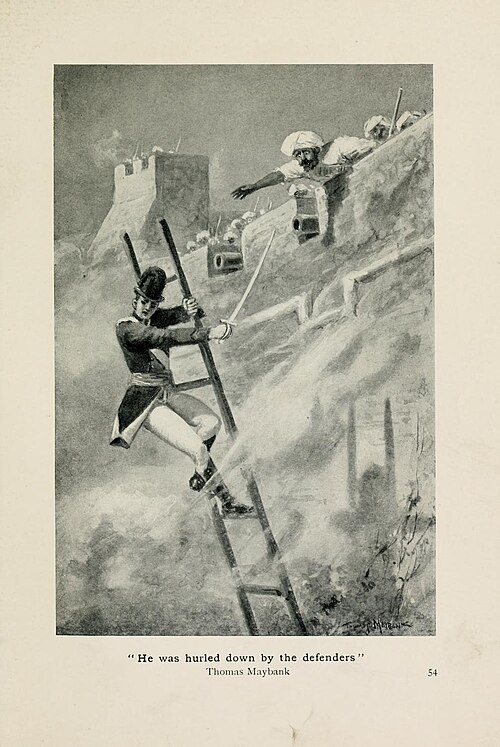

The British East India Company (EIC) captured Ahilyanagar during the Second Anglo-Maratha War (1803–1805). The Ahmadnagar Fort, a stronghold under the control of the Scindia faction of the Marathas, became an early target for the British. On 8 August 1803, the British laid siege to the fort under General Arthur Wellesley (later the Duke of Wellington). After a brief but intense bombardment, the British successfully breached the fort's walls using artillery and stormed the stronghold. The fort fell to the British on 12 August 1803. The fall of Ahmednagar gave the British a strategic advantage in the Deccan region and disrupted the Maratha Confederacy’s territorial control.

Annexation of Ahmednagar

Following their defeat in key battles, including the loss of Ahmednagar (present-day Ahilyanagar), the Scindias signed the Treaty of Surji-Anjangaon with the British East India Company in December 1803. Under this treaty, Daulat Rao Scindia ceded significant territories to the British, including Ahilyanagar and other strategic regions in western India.

Although the British gained control of the district after the treaty, the region remained politically unstable due to resistance from other Maratha factions. During the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1818), the British decisively defeated the Maratha Confederacy, including the Peshwas. After the fall of Baji Rao II (the last Peshwa) in 1818, the British formally annexed all remaining Maratha territories, including Ahmednagar, into British India. Following the defeat and exile of Peshwa Baji Rao II, the British dissolved the Maratha administrative system and integrated Ahilyanagar into their governance structure. Under British administration, Ahilyanagar became an important military and administrative center, remaining as a part of the Bombay Presidency until India's independence in 1947.

The district gradually came under full British control through negotiated territorial cessions rather than a single conquest. According to the Gazetteer (1884), in 1822, the Nizam ceded 107 villages to the British through a treaty dated 12 December 1822. These villages were distributed across Nagar, Jamkhed, Shrigonda, Karjat, and Shevgaon. In 1861, Scindia ceded 120 villages to the British in exchange for other lands. These villages were located in Nagar, Parner, Shrigonda, Karjat, Nevasa, Shevgaon, and Kopargaon. In 1868, Holkar ceded three villages in Shrigonda on 30 December 1867. Additionally, one village in Kopargaon was ceded 28 November 1868. In 1870, the Nizam ceded two villages in the Nagar sub-division in exchange for other lands on 22 July 1870.

In the administrative history of the Ahilyanagar district, the year 1869 stands out significantly. This is because in that year, parts of Nashik and Solapur that were previously part of Ahilyanagar district were separated. This division resulted in the formation of the present-day Ahilyanagar district, signifying a notable administrative and territorial change.

First War of Independence, 1857

Evident in the events of 1857, the local communities were assertive in their position against British rule. The locals’ active involvement in the struggle, under the leadership of renowned freedom fighters, indicated a strong determination to resist British dominance and fight for their freedom.

During the revolt of 1857, the district witnessed significant unrest. It is recorded that approximately 7000 individuals from the Bhil community, led by Bhagoji Naik, actively participated in the struggle. The hilly regions and areas like Parner, Jamgaon, Rahuri, Kopargaon, and Nashik became the site of contestation. However, despite their efforts, all attempts to overthrow British rule ultimately failed, leading to the continuation of British domination.

Local Libraries

In the 1880s, Ahilyanagar had few libraries underlining the town's commitment to intellectual pursuits, and the preservation of its literary heritage amidst changing socio-political dynamics.

Ahmednagar City Library: Established in 1838, the library faced periods of closure due to lack of support but has remained open since 1847. It is housed in a former mosque, and has a collection of 1533 books, primarily in English but also includes Marathi, Sanskrit, and Persian literature. In 1882-83, it had fifty members paying yearly subscriptions ranging from Rs. 3 to Rs. 24. The annual revenue of the library amounts to about Rs. 420, with Rs. 300 collected from subscriptions and Rs. 120 granted from municipal funds. The library subscribes to several English and vernacular newspapers, and magazines.

Sangamner Library: Despite its small size, this library had its own building. It housed a collection of seventy books, mainly in Marathi, with a few in Sanskrit and Gujarati. In 1882-83, there were 34 subscribers paying yearly subscriptions ranging from Rs. 1.5 to Rs. 12. The annual income of the library is approximately Rs. 118, with Rs. 48 contributed by the Sangamner town municipality and the remainder, by subscribers.

Female Educational Advancement

Significant expansion in girls' education in Ahilyanagar is recorded, demonstrating a growing awareness and importance placed on female literacy and schooling. According to the Gazetteer (1884), the first girls' school was established in Ahilyanagar in 1840.

Perhaps, it was the same endeavor that was overseen by American missionary Cynthia Farrar, who was active in the district at the time. Farrar served as a teacher and established the girls' schools in both Bombay (present day Mumbai) and Ahmednagar (present day Ahilyanagar). She was among the first single American women recruited as missionaries to work abroad.

In 1826, the Marathi Mission of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions requested the deployment of a single female missionary to direct schools for girls in Mumbai, relieving the wives of male missionaries from this responsibility. Despite previous reluctance from American missionary societies to send single women missionaries abroad, Farrar was recruited as the Superintendent of Girls' Schools. Departing from Boston on 5 June 1827, as part of a missionary group bound for India, Farrar assumed her duties in Bombay on 29 December 1827.

In 1839, Farrar was assigned to Ahilyanagar to establish and oversee schools for girls. In 1848, Jyotiba Phule (one of the freedom fighters) visited Farrar's school in Ahilyanagar and was inspired to establish a girls' school in Pune. This marked the first-ever school for girls founded and operated by an Indian.

One of her notable students was Savitribai Phule (wife of famous social reformer Jyotiba Phule), a pioneering Indian feminist and educator, who enrolled in an education and teacher training program under Farrar's guidance. Savitribai later began teaching a small group of girls with Farrar's assistance. Farrar continued her work in Ahmednagar until her passing in 1862.

According to the Gazetteer (1884), by 1868, there were 59 enrolled students with an average attendance of 25.2. Between 1872-1878, an additional school was opened, bringing the total number of pupils in both schools to 148. In the subsequent years, from 1882-1888, the number of schools increased to 19, with 1123 enrolled students and an average attendance.

Ahmednagar Sarvajanik Sabha

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the intellectual and political currents of the Bombay Presidency began to manifest in the district. In 1871, under the influence of the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, the Ahmednagar Sarvajanik Sabha was established. Although little documentary evidence survives regarding its sustained activity, it was likely intended to serve a similar function—that is, to act as an intermediary body between the colonial authorities and the local populace, particularly with respect to agrarian concerns.

Journalism

In the 1880s, the district was known for its local Marathi newspaper publications. There were three Marathi newspapers printed in Ahmednagar. These include:

- Nyayasindhu or Ocean of Justice: a lithographed paper (lithography is a printing technique that involves creating an image on a flat stone or metal plate and transferring it onto paper) that was circulating for eighteen years.

- Nagar Samachar or Nagar News was in circulation for about ten years.

- Jagaddarsh or Mirror of the World was in circulation for two years.

Struggle for Independence

The district holds historic significance in India's struggle for independence, serving as a site for several prominent local leaders. When Lokmanya Tilak spearheaded political movements across India until his imprisonment by the British government, the district actively participated. After his death in 1920, Mahatma Gandhi assumed leadership and organized Civil Disobedience Movements, encouraging thousands to participate in Satyagraha and face arrest. Satyagraha movements occurred multiple times between 1920 and 1941.

The Quit India Movement, 1942

The most intense phase of local participation occurred during the Quit India Movement, initiated by the All India Congress Committee on 9 August 1942. In Ahmednagar and its surrounding talukas, spontaneous protests, processions, and acts of civil defiance took place.

Among the notable individuals active in this period was Madhav Ganpat Kohokade, born in 1919 in Rahuri village. Affiliated with the Congress Gram Seva Dal from 1937 to 1940, Kohokade was involved in grassroots political organisation. In August 1942, he led a rally at the Rahuri Tehsil office in support of the Quit India resolution. He was subsequently arrested and sentenced to six months' imprisonment at Yerawada Central Jail in Pune. During his confinement, Kohokade reportedly raised concerns regarding prison conditions and maintained his commitment to Gandhian principles.

Another figure of local significance was Bhika Tukaram Palande, born in 1912 at Dadh Budruk. During the upheaval of 1942, Palande provided refuge to underground activists on his farmland and collaborated with Bhaskarnana Durve, a regional leader of the movement.

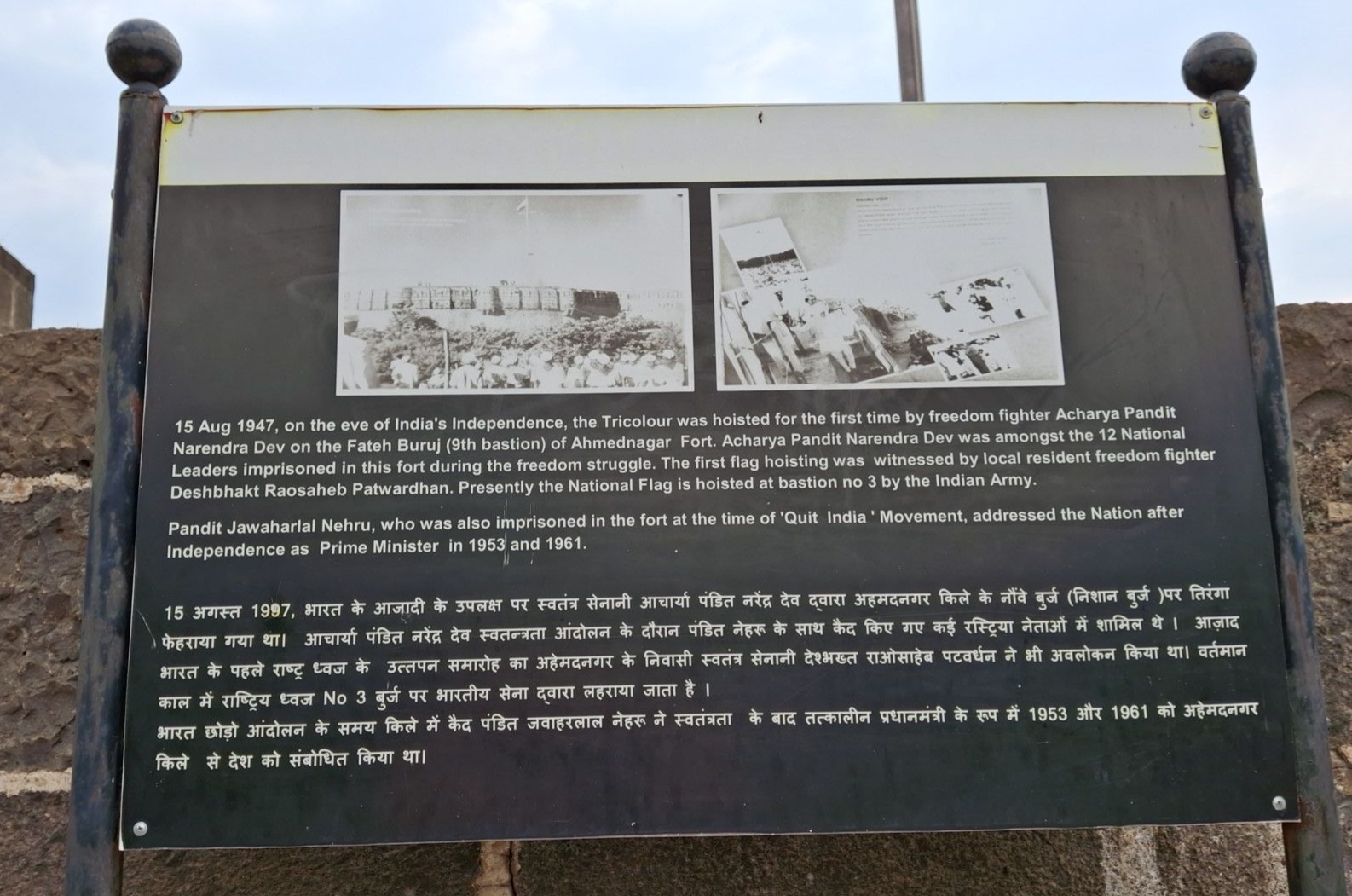

Ahmednagar Fort as a Political Prison

It was during this same movement that the Ahmednagar Fort, which had previously served as a battleground between various dynasties (mentioned above) assumed a more symbolic role in the national consciousness. Several leading figures of the Indian National Congress—including Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel—were detained within its walls between 1942 and 1944.

During the Quit India detention, the inmates were kept in separate quarters but were permitted to correspond with family, read selected newspapers, and convene for discussions. Their days were marked by intellectual activity, writing, and occasional recreation. Health concerns were common among the detainees, attributed in part to age and limited medical facilities.

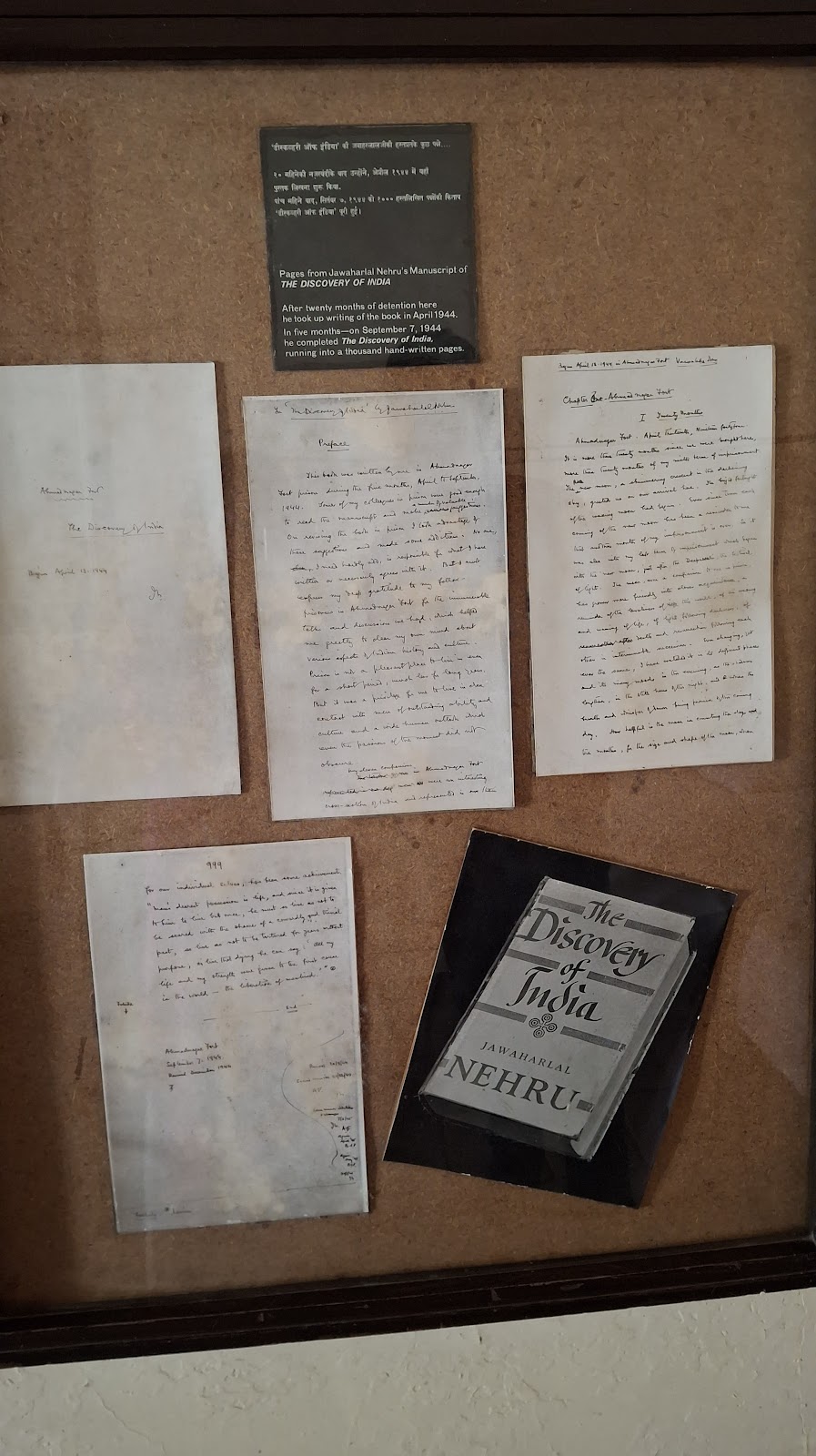

It was within the Leader’s Block that Pandit Nehru composed his seminal work, The Discovery of India, between April and September of 1944. The room he occupied remains preserved, with furnishings and layout left undisturbed, and is now accessible to visitors.

Post-Independence

When India gained independence on 15 August 1947, the Bombay Presidency, including Ahilyanagar, became part of the Bombay State. However, on 1 November 1956, the State underwent reorganization under the States Reorganisation Act, based on linguistic lines. This reorganization absorbed various territories, including the Saurashtra and Kutch States, which ceased to exist. Then, on 1 May 1960, Bombay State was dissolved and split along linguistic lines into two separate states: Gujarat, with a Gujarati-speaking population, and Maharashtra, with a Marathi-speaking population.

Technological Progress

The district emerged as a center for research and development in the field of vehicles and automotive technology. Post-Independence, Vehicle Research & Development Establishment (VRDE) was relocated to Ahilyanagar and renamed Technical Development Establishment (Vehicles) or TDE (V). Originally, it was established in 1929 with the Chief Inspectorate of Mechanical Transport (CIMT) at Chaklala, which falls in Pakistan.

Further developments occurred in 1965 when the activities were divided into research and inspection, leading to the creation of two separate establishments: VRDE and Controllerate of Inspection Vehicles (CIV), later known as Controllerate of Quality Assurance Vehicles (CQAV). A detachment of VRDE was established in Avadi, Madras in 1966 to assist in tank production, eventually leading to the formation of Combat Vehicles Research and Development Establishment (CVRDE).

VRDE has evolved from vehicle modifications and technical evaluations to developing futuristic vehicles. It houses the National Centre for Automotive Testing (NCAT), which caters to testing and evaluation needs of defense services and the automotive industry. Additionally, VRDE established India's first and one of the world's largest Automotive Electro-Magnetic Compatibility (EMC) test facilities, also known as EMC Tech Centre. The establishment is also working on projects such as the Energy Research Centre and the National Centre of Excellence for Combustion and Gasification (NECG).

Cavalry Tank Museum

In 1994, a unique Cavalry Tank Museum was established by the Armored Corps Centre and School. It was a significant milestone in the preservation and celebration of military history.

The museum showcases approximately 50 exhibits of vintage armored fighting vehicles. Among the exhibits, the oldest is the Silver Ghost Rolls-Royce Armored Car (Indian Pattern), dating back to the First World War era and having served on battlefields such as Cambrai, the Somme, and Flanders. The collection also includes vehicles from the Second World War period.

Notable exhibits feature British Valentine and Churchill Mk. VII infantry tanks, a Matilda II tank, an Imperial Japanese Type 95 Ha-Go light tank, a Type 97 Chi-Ha medium tank, a US Sherman Crab mine-flail tank, a British Centurion Mk. II main battle tank (MBT), a Nazi German Schwerer Panzerspähwagen light armored car, and an Indian Vijayanta MBT. Additionally, the museum displays a British Archer tank destroyer, a Canadian Sexton self-propelled artillery vehicle, US M3 Stuart and M22 Locust light tanks, an American M3 Medium Tank, and various armored cars from different conflicts and eras.

A notable artifact is the Nazi German 88mm anti-aircraft/armor field-gun, captured from the German troops, possibly belonging to the 15th Panzer Division of the Afrika Korps, as indicated by the divisional markings on the artillery-piece.

The museum also houses war-trophy tanks acquired from the Pakistani military during the Indo-Pakistani Wars of 1965 and 1971, including an American-made M47 Patton medium tank, WWII-era Chaffee, and Cold War-era M41 Walker Bulldog light tanks. Additionally, it features an Indian AMX-13 light tank of French origin from the 1950s and a PT-76 amphibious/light tank from the same period. The museum's Memory Hill is dedicated to housing souvenirs from all regiments of the Indian Army's Armored Corps.

Sources

BalKrishna. 1932.Shivaji the Great: Volume 1. D. B. Taraporevala Sons.

Charles Augustus Kincaid; Dattatraya Balwant Parasnis. 1918.A history of the Maratha people. H. Milford, Oxford University Press.

Disha Ahluwalia. 2024.Daimabad was home to skilled agriculturalists—even before Harappans’ cultural influence.ThePrint.https://theprint.in/opinion/daimabad-home-to…

ETOnline. 2023.Ahmednagar renamed as Ahilya Nagar: Maharashtra Cabinet approves name change. The Economic Times.https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/in…

Frank Moraes. 2007.Jawaharlal Nehru. Jaico Publishing House.

H. Nanjudiah, P. Setu Madhava Rao et. al . 1976.Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Ahmadnagar District.Bombay, Department of District Gazetteers.

Herbert Hope Risely. 1911. Imperial Gazetteer of India. Vol. 2. The Bombay Government Press.

Husbandman. 1884.Gazetteer Bombay Presidency Ahmednagar. Vol.1. The Bombay Government Press.

James, Edward T. James, Janet Wilson, and Boyer, Paul S.Notable American Women, 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary,Volume 2, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971.

Lakshmi Subramanian. 2020.Kedareshwar Cave at Harishchandragad, Ahmednagar, Maharashtra. Sāhasa.https://sahasa.in/2020/08/17/kedareshwar-cav…

Nanjundiah, H., et al. 1976.Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Buldhana District. Bombay: Department of District Gazetteers.

Nayana Jambhe.Harishchandragad Trek. IndiaHikes.https://indiahikes.com/documented-trek/haris…

Patil, Vishwas (2016).Sambhaji. Pune: Mehta Publishing House.

Pradeep P. Barua.The State at War in South Asia. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

R. V. Oturkar. 1956. “A study of the movements of Shahaji (Shiwaji's father) during the period of 1624-30”.Proceedings of the Indian History Congress,19.

Radhey Shyam. 1966. The Kingdom of Ahmednagar. Motilal Banarsidass.

Satish Chandra. 2005. Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals. Har-Anand.

Unsung Heroes Detail. n.d.Lt. Madhav Ganpat Kohokade.https://amritmahotsav.nic.in/unsung-heroes-d…

Z. D. Ansari, M. L. K. Murty, R. S. Pappu. 1976-77. The Acheulian Horizon At Chirki-Nevasa And Its Chronological Implications. Vol. 36, Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute.https://www.jstor.org/journal/bulldecccollre…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.