AMRAVATI

Architecture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Architecture of Prominent Sites

Amravati district’s architecture reflects a layered history shaped by shifting dynasties, regional traditions, and evolving religious and cultural influences. Forts, stepwells, mandirs, and tombs across the district reveal a confluence of styles, ranging from indigenous hill fort architecture to Persian-inspired Indo-Islamic designs. Each site marks a different facet of Amravati’s past: the military stronghold of Gavilgarh Fort, the water management ingenuity of Mahimapur Chi Vihir, the royal funerary landscape of Bebah Bagh, the distinctive tower of Hauz Katora, and the labyrinthine religious spaces of Datta Mandir. Together, these structures trace the district’s architectural journey, offering insights into its diverse historical contexts, religious continuities, and adaptations over time.

Gavilgarh Fort

Gavilgarh Fort (Gavilgadh) is a historic hill fort located north of the Deccan Plateau near the Melghat Tiger Reserve in the Amravati district. Constructed by the Gavli community, who were rulers of the shepherd community in the 12th–13th century, the fort later came under the control of the Gonds, followed by the Mughals.

The fort’s architecture includes three gateways, two water tanks, and remnants of defensive walls and bastions. Notable features include finely carved panels depicting elephants, bulls, tigers, and lions, as well as inscriptions in Hindi, Urdu, Arabic, and Persian. Murtis of Bhagwan Hanuman and Bhagwan Shankar are situated within the complex, reflecting its religious significance. Ten surviving cannons, crafted from iron, copper, and brass, testify to its military history.

Designated as a protected monument by the Archaeological Survey of India, Gavilgarh Fort today attracts visitors for its architectural heritage and panoramic views of the surrounding Melghat region.

Mahimapur Chi Vihir

Mahimapur Chi Vihir follows a multi-storeyed stepwell architectural style influenced by the Yadava, Bahmani, and Nizam Shahi periods. Located in Mahimapur village of Daryapur taluka, the stepwell is believed to date back to the 13th century, with later additions possibly from the Mughal period. It was likely built to address water scarcity and provide shelter to travelers.

Mahimapur Chi Vihir is a square-shaped stepwell measuring about 40 meters by 25 meters and around 80 to 100 ft. deep. The structure features seven levels connected by 85 to 88 stone steps, each floor marked by stone arches resembling fort gateways. The entrance spans 250 sq. ft. and is decorated with two carved stone flowers. The well’s construction primarily uses colored stone, with rare black stone sections said to have been sourced from Bahiram (a village that lies on the borders between Amravati and the Betul district of Madhya Pradesh). Inside, the design allows visitors to walk and sit along the four sides of the well, with the bottom resembling a riverbed.

A distinctive feature of the stepwell is the Sopan (resting area) located between the 10th and 12th steps. The final nine steps, arranged in an A-shape, lead to a small Mandir dedicated to Devi Mahimamai, the Devi after whom, according to locals, the village is named. Archaeological finds, including pillars and a Nandi statue, are believed to date back to the Yadava period. The stepwell is also noted for having twelve doorways and intricate carvings that add to its architectural richness.

Mahimapur Chi Vihir is a state-protected monument, though it remains minimally documented and lacks active conservation efforts, with only a plaque by the Archaeological Department marking the site.

Bebah Bagh

Bebah Bagh, also known as Shahi Qabristan, exemplifies the Indo-Islamic architectural style with strong Persian influences. Located in Achalpur’s Sarmaspura area, around two kilometers from Hauz Katora, it was originally established as a royal cemetery during the Nizam Shahi period approximately 250 years ago. The site later evolved into a landscaped garden, possibly giving rise to its current name.

Bebah Bagh is characterized by intricately carved tombs, latticed windows, and arched doorways adorned with floral and geometric motifs. These features reflect the refined craftsmanship associated with Nizam Shahi architecture. The arched entrances, with their delicate stone carvings, stand as key examples of the site’s architectural style. Although many original elements remain intact, the garden’s layout and surroundings have undergone significant changes over time.

Hauz Katora

The Hauz Katora reflects the Pathan architectural style popular during the Imad Shahi dynasty (1490–1572 CE). Situated along Bhilona Road in Achalpur, this 16th-century octagonal tower was built of brick, mortar, and sandstone, rising around 80 feet from the remnants of what was once a 300-foot-wide circular tank.

The structure’s distinctive design—with stairs connecting only the second and third floors, but not the first and second—has intrigued historians and researchers alike. Some locals suggest the tower functioned as a summer retreat, while Dr. Vaibhav Mhaske in an ETV interview in 2024 suggested it once served as a nauka vihar (yachting center), drawing visitors from across Western Maharashtra and South India. Historically, water possibly reached the level of the first floor, allowing boats to dock directly beneath the second floor which explains its unique staircase arrangement.

Architectural features of Hauz Katora include open arch-shaped doors on all eight sides and intricate creeper motifs carved along the interior. Originally believed to have five stories, only three remain today; upper levels were dismantled by a Nawab for building materials. Although the surrounding tank has since silted up and lost its form, the tower stands as a fascinating remnant of Achalpur’s medieval history.

Datta Mandir

Datta Mandir in Sultanpura is notable for its unique labyrinthine design, a feature that has earned it the local nickname “Bhool Bhulaiya” or maze mandir. Its architectural style blends traditional mandir design with an intricate layout of interconnected pathways leading to shrines dedicated to various Devis and Devtas, including Ganesh, Shiv, and Ram-Sita.

The Mandir’s interior features a wooden framework and arches. The Mandir also showcases ancient paintings and sculptures that highlight its enduring religious and cultural significance. Among its most distinctive artifacts is a century-spanning calendar, covering the years 1923 to 2023, which chronicles key milestones in the Mandir’s history.

Residential Architecture

In Amravati, each structure carries the imprint of local history, community life, and a distinctive cultural identity. As modern structures replace them, remnants—like ornate doorways or decorative windows—remain as glimpses into past ways of life and building traditions.

These architectural elements not only preserve physical remnants but also carry deeper meanings about how past societies understood and experienced their living spaces - insights that are perhaps becoming increasingly distant from modern ways of living.

An 18th Century Residential Space at Malipura

Malipura is a small village that is situated in the Achalpur taluka of Amravati district. The settlement here is believed to be at least a century old. Within the village stands a single-storey house, estimated by locals to be around 250 years old. The house is part of a dense cluster of wadas and havelis (traditional mansions built from locally sourced mud and wood).

These homes, shaped by an older architectural language, offer a striking contrast to the new concrete buildings that now define much of the village’s growing landscape. Yet, in this quiet juxtaposition, they offer a rare, and increasingly important, insight into the architectural heritage of the village.

The house is positioned along one of the narrow lanes characteristic of the village’s settlement pattern, where homes are tightly packed together. Small aangans (courtyards) in front of the homes often serve as the only open spaces within this dense arrangement.

The street itself carries a sense of intimacy, with its narrow width encouraging social interaction among residents. Yet, within this close-knit setting, the 250-year-old residence makes a dramatic architectural statement through its imposing entrance gate. At 6.5 to 7 ft tall, and crowned with arches, the gate conveys a sense of grandeur and dominance that stands in striking contrast to the humble scale of its surroundings. According to the homeowner, this design follows a tradition from 150 to 200 years ago when large gates were used to symbolize royalty and high social status. The towering entrance remains a visual reminder of a family’s elevated position within the community.

Interestingly, however, the inner doors of the residence tell a different story from the grandeur of the outer ones. Measuring only 4 to 4.5 ft. in height, these interior doors require one to bow while passing through. This design is deliberate, the elder matriarch of the house suggests, and carries a deep cultural meaning.

The small doors, she notes, serve as a reminder to bow before the higher power for all the blessings they have given in one’s life. This architectural choice perhaps reflects a broader cultural practice, where physical posture is used to express respect and gratitude. Intriguingly, this architectural feature is, as locals say, a common characteristic of many homes across the region, illuminating how cultural values are integrated into the very design of spaces.

The residence follows a T4 typology (a technical term for four room houses). Though renovated in 1996, including updates to flooring, plaster, and paint, the residence maintains much of its original character.

The structure features a distinctive design, characterized by a diverse use of materials that contribute to its unique character. The exterior walls are built with brick, while the stairs and verandah are crafted from slate stone. This blend of materials provides a striking contrast and a sense of permanence to the building.

Inside, the residence features wooden roofing supported by sturdy wooden pillars. Notably, the district Gazetteer (1968) notes that Achalpur, the taluka to which Malipura belongs, “had a reputation also for wood-carving and stone-work.” This legacy can perhaps be seen in the intricate wooden details on the doors and other elements of the structure.

Mosaic tiles have recently been laid down in place of the original earthen floor, marking an update to the home’s interior.

The exterior of the residence is finished in white and earth tones, while the interior features soft pastel shades. Locals mention that this color scheme is widely adopted throughout the village and some parts of the district.

The doors of the residence are predominantly made up of wood, each featuring distinct carvings with geometric or nature-inspired motifs. All of the doors are double doors, each has decorative borders, trims, and a central divider, a design repeated in other doors around the house.

Additional exterior doors on the property also showcase the signature geometric and leaf motifs seen throughout the house, creating a sense of cohesion. However, each door has its own distinct variation.

For instance, one door features an arch-like structure with elaborate embellishments, while another maintains a simpler, more understated design. These variations subtly contribute to the overall architectural diversity in the house. Additionally, the interior doors, as mentioned above, are smaller in size compared to the exterior ones.

The windows in the residence are said to be fewer in number than the doors, with the size of each varying based on location. Many feature double-door designs, mirroring the door construction, though they lack a uniform symmetry or style. Some windows are adorned with arches and motifs, which add an extra layer of charm to the space. A number of them feature metal railings, which were likely added during renovations. Interestingly, some of the windows are positioned lower than usual, possibly to improve ventilation.

The windows feature wooden frames, and each is separated by a sill that creates a distinct boundary between interior spaces and the window openings.

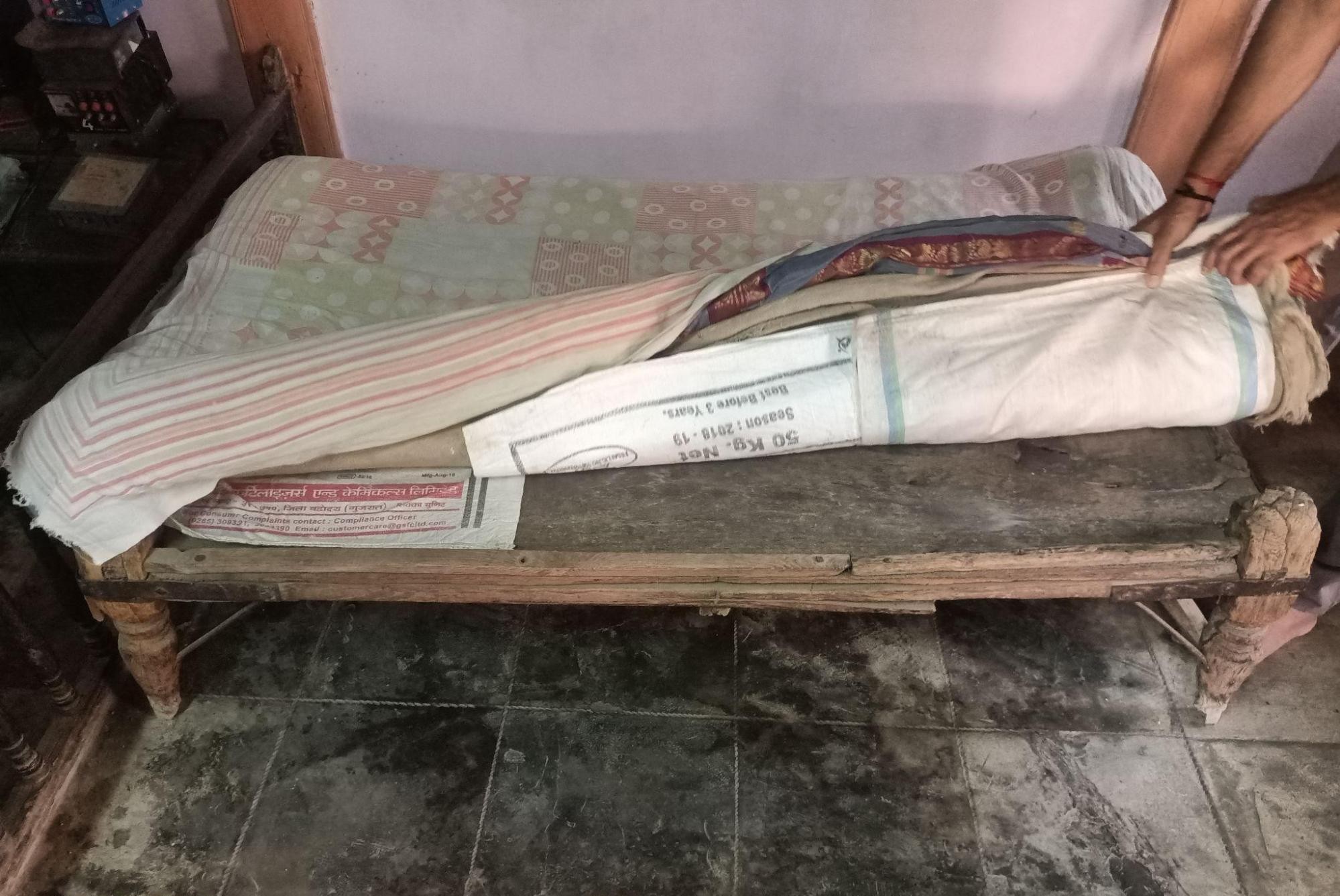

The residence contains a variety of traditional furniture and tools that reflect the local culture and heritage. These items are characterized by their specific regional nomenclature and practical functions. Though many of these objects are less commonly used today, they remain a significant part of the household’s history and identity.

For instance, a storage chest, colloquially referred to as Munimji Chi Peti was once commonly used for securing valuables and household essentials and today serves as a practical remnant of the past. Similarly, the Takhatposh, a traditional wooden bed, was widely used in earlier times but is now a rarity. These pieces, along with others found in the home, provide a window into domestic life of earlier periods, reflecting both utility and regional craftsmanship.

Foldable seating options, such as the Baithak and Aaram Khurchi, were common in the past and are still preserved here. Additionally, Kanode (shelves) are built into the walls of the residence, demonstrating a functional approach to space.

In addition to the traditional furniture, the structure of the residence incorporates several architectural elements that exemplify thoughtful design and environmental responsiveness. Central to these features is the chowk, a key architectural component that serves both functional and environmental purposes.

Positioned at the center of the terrace, the chowk functions as a light well, channeling natural light into the interior spaces. Simultaneously, it supports a traditional water harvesting system, reflecting a sustainable approach to managing natural resources. This integration of passive lighting and water management illustrates the careful consideration of environmental factors in historical residential architecture.

The chowk is complemented by jharoke or wawne, traditional ceiling apertures that function as skylights. These architectural elements, found throughout the house, seem to allow natural light to enter while contributing to air circulation. Such features suggest how regional architectural practices might have inculcated solutions for climate control and interior illumination before the advent of mechanical systems.

The residence also contains various tools and artifacts from earlier times. For instance, the presence of defensive implements, including wall-mounted spears and swords, provides insight into domestic security concerns of earlier periods.

The presence of a British-style mirror from the 1880s points to how households naturally accumulated and integrated objects from different historical periods, each adding to the evolving material culture of domestic spaces.

Traditional elements such as jhumbars (hanging fixtures) and a designed paath in the kitchen area represent typical decorative and lighting features through different periods.

The exterior features of the structure include functional elements that reveal attention to daily needs of its residents. Water storage systems, being an essential component of traditional homes, are integrated into the structure.

The building has parapet walls, known locally as mundale, along its perimeter, while ventilation features appear throughout the exterior walls, suggesting consideration for air circulation.

The presence of decorative cornices to both exterior and interior walls indicates attention to architectural detailing characteristic of the period it might have been built in.

In addition to this, the residence includes traditional decorative or design elements that can be commonly found across the country. A bangayee or jhula (traditional swing) and a tulsi-vrindavan near the entrance door represent common features of traditional Indian homes, where they serve both functional and cultural purposes.

The property also features significant ancillary spaces that support its primary functions. Ancillary spaces, as scholars Aarti Verma and Abhijit Natu (2020) note, are such structures when it comes to “residential architecture,” that “primarily facilitate leisure activities.” Such spaces could be private gardens, storage rooms or more. The ancillary space within this residence includes a garden space which was previously utilized as a gai wada (cow shelter).

Today, this space has been repurposed for growing lemon and seasonal fruit trees, showing how spaces within historical homes continue to serve the needs of their residents.

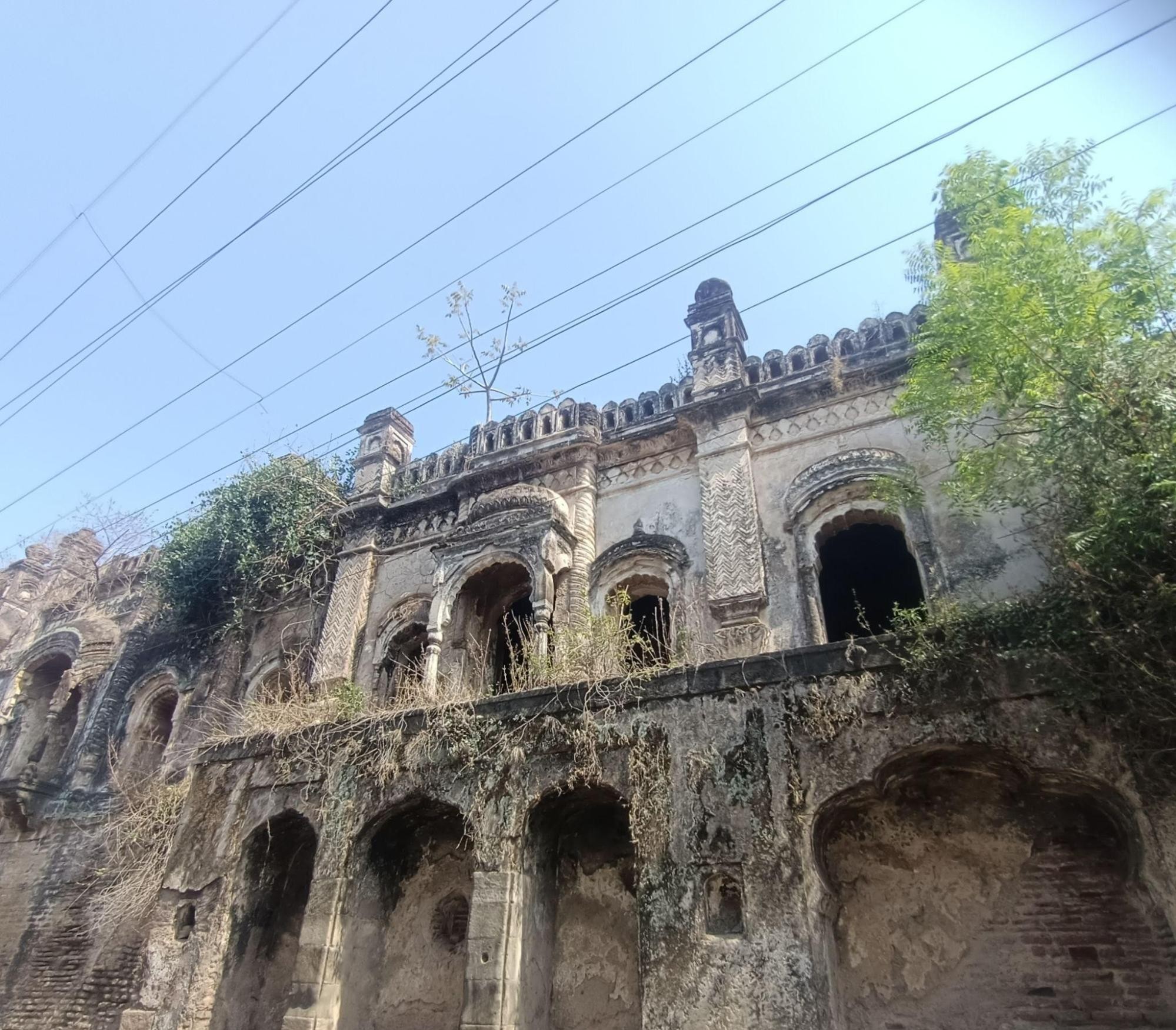

A 20th-Century Residence in the Sultanpur Fort Precinct

Sultanpur fort, while lesser-known in the district, lends its name to the village that surrounds it. In a Durgbharari article, it is noted that the fort was likely built by a chieftain for personal security at least 300 years ago. Today, the fort stands in a deteriorating state, its former structure diminished by time.

Within this historic precinct stands a residence built approximately 85 years ago. The structure, following a T3 typology (a dwelling that typically comprises three rooms), rises two storeys and underwent renovations in 2013 that included updates to flooring, painting, and wall plaster.

The residence occupies a corner plot formed by the intersection of two lanes. The left side opens onto a residential street characterized by houses built two to three decades ago. While many neighboring structures have been renovated, medieval influences remain visible in their design. Nearby stands the prominent Datta Chakabhuli Mandir, notable for its bhool bhulaiya (maze-like) design.

What makes this residence particularly interesting is its composition of two distinct structures - one dedicated to private living spaces and the other to social and utilitarian functions. The most captivating aspect is how one of these structures contrasting facades at its corners. This distinction, notably, is created through the use of different materials where one facade showcases traditional brickwork while the other reveals elaborate wooden elements.

The composite structure of both spaces comprises brick walls bonded with a limestone and fine sand mixture, with this same limestone mixture extending to the wall finishing as plaster. The interior construction showcases extensive woodwork in its pillars, ceiling, and flooring. The color palette transitions from pastel exterior finishes to purple and pink interior walls in the hall and kitchen respectively.

The residence features three main entrance gates. The doors are crafted predominantly in wood, with each displaying distinctive carved motifs of geometric patterns. These double-doored entrances are characterized by decorative borders, trims, and central dividers. Fascinatingly, the design of these dividers shares similarities with those in the centuries-old residence in Malipura documented above, pointing to perhaps domestic woodworking style and traditions in the region.

The windows, though different in size, all follow the same double-door design, with metal safety rails that were perhaps added more recently.

As noted earlier, the property's corners present contrasting facades through their distinct materials. This material distinction extends to the upper-level barriers - featuring wooden railings with latticed panels on one corner, while the other corner employs a cement parapet wall with geometric jaali work, maintaining the building's distinct material vocabulary.

The residence features traditional Mangalore tile roofing with overlapping clay tiles. The roofing structure is supported by an exposed wooden framework of rafters and battens, visible from the interior. These wooden members, arranged in a triangular configuration, form the structural support for the clay tiles above.

While most of the roof uses traditional materials, some sections incorporate metal sheet roofing, indicating later modifications to the original structure. This combination of roofing materials - traditional clay tiles and modern metal sheets - reflects the building’s evolution over time. It demonstrates how the residence has adapted to changing materials and needs through different periods.

A Traditional T1 Dwelling in Wastapur Village

Wastapur is a village that was formed after its residents were relocated due to the Melghat Tiger Project. The fertile land that surrounds Wastapur plays a crucial role in shaping both the livelihood of its people and the character of its built environment. Dairy farming, the primary occupation here, influences how homes are laid out, with many designed to accommodate cattle alongside living spaces. The architectural landscape of the village is one in transition. Traditional homes and newer cement houses create a patchwork along its streets.

Many recent dwellings, constructed under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana – Gramin (PMAY-G) scheme, mark a departure from the village’s traditional building practices.

Amidst this changing landscape stands a 55-year-old house built in the T1 typology (a one-room dwelling). This home preserves much of its original character while continuing to serve its residents’ daily needs. Its presence quietly honors the region’s older housing traditions as newer architectural forms reshape the village.

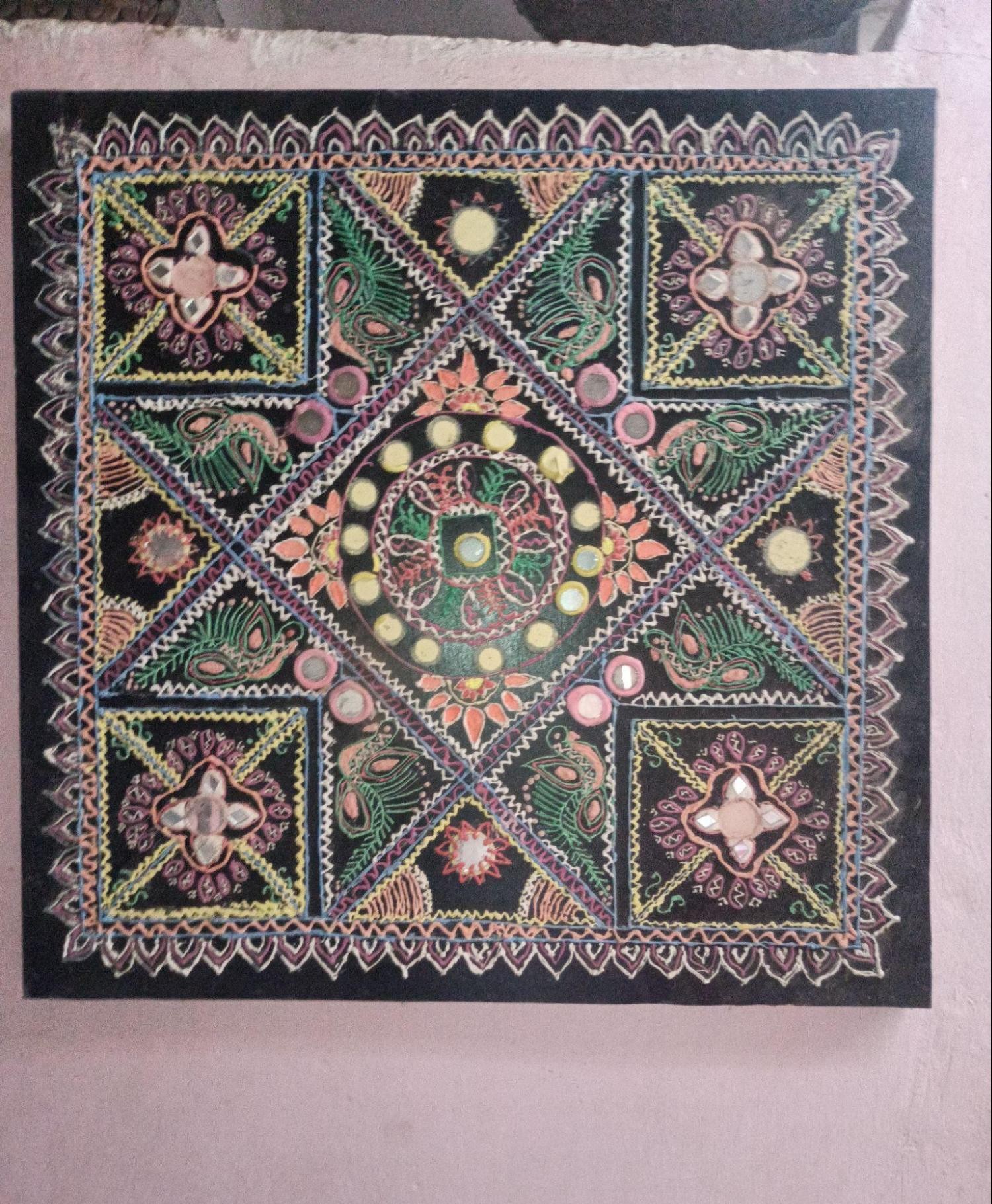

The architectural elements within the residence offer a glimpse into the layered history and evolving design traditions of the village. These traditions are particularly evident in the doorways and entrances. The main entrance, for instance, is flanked by red-painted niches, each with carved or embossed writing above—likely the name of the owner or family. This decorative treatment of the entrance is a distinctive feature of the residence.

The house has traditional wooden double doors throughout. While all maintain basic solid wood construction with paneled designs, their decorative elements vary considerably. These different styles, along with varying states of preservation perhaps point to renovations made during different periods.

Most of the windows in the house appear to be ventilation windows or clerestory windows. The windows have vertical planks divided into two sections (upper and lower panels), separated by wooden plank and metal frame.

Both windows appear to be designed for ventilation purposes, with a simple plank construction.

The roofing system of this residence features a traditional timber construction, with rafters and purlins placed to support the structure from within. The design incorporates a sloped roof, a characteristic common in regions that experience substantial rainfall. The absence of a false ceiling leaves the structural members exposed, showcasing the intricate framework of the roof. This open design allows natural light and ventilation to permeate the interior space.

The timber beams, aged with time, add character to the space. Some gaps in the roofing allow daylight to stream in, connecting the interior to the surrounding environment.

Sources

Aarti Verma, Abhijit Natu. 2020. Integral Elements of Residential Liveable Environments: Private Gardens.Vol 9, no 1. International Journal of Architecture, Engineering and Construction.http://dx.doi.org/10.7492/IJAEC.2020.005

ETV Bharat. 2024. 500-Year-Old Historic Hauz Katora Building in Achalpur, Amravati. ETV Bharat. Accessed March 17, 2025.https://www.etvbharat.com/mr/!state/500-year…

Explore with Dr. Jayant Wadatkar. 2018. Mahimapur Step Well. Youtube.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bhuRks0Vc2Q

Incredible India. Gawligadh Fort. Incredible India. Accessed March 17, 2025.https://www.incredibleindia.gov.in/en/mahara…

Lokmat News Network. 2022. There is a mysterious well from the 13th century in Mahimapur, Amravati district. Lokmat. Accessed on May 9, 2025.https://www.lokmat.com/amravati/mahimapur-in…

Maharashtra State Gazetteer. 1968. Amravati District. Directorate of Government Printing, Stationary & Publications, Mumbai.

Maharashtra State Gazetteer. 1977. Amravati District. Directorate of Government Printing, Stationary & Publications, Mumbai.

Sultanpura.Durgbharari. Accessed 22 Jan 2025..https://durgbharari.in/sultanpura/

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.