Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Rishi Kardam & the Legend of Tulja Bhavani

- Ter - a Trading Centre during the Satavahana Period

- The Spread of Buddhism and the Fall of Ter

- Rashtrakutas and Jain Excavations at Dharashiv Leni

- Shilaharas and their Possible Connection to Ter

- Chalukyas & the King Nal of Naldurg

- Yadavas & Hemadpanthi Mandirs

- The Tulja Bhavani Mandir and the Kadamb Lineage

- Sant Gora Kumbhar

- Medieval Period

- Rule of the Delhi Sultanate in the Deccan Region

- Bahmani Rule and Administrative Reorganizations

- Local Governance under Khvaja Jahan at Paranda

- Naldurg under Siege (1580-81)

- Paranda and the Campaigns of Burhan Nizam Shah

- The Rise of Malik Ambar and Paranda as the New Capital

- Sustained Resistance and Mughal Annexation

- Aurangzeb’s Campaign for Paranda Fort

- Shivaji and the Legend of the Bhavani Talwar

- Afzal Khan’s Campaign and the Attack on Tuljapur

- Capture of Naldurg and Mughal Military Gains

- The Battle Near Tuljapur, 1690

- The Jagir of Bhoom

- Osmanabad as Sarf-e-Khaas Territory under the Nizams

- Battle of Palkhed and Maratha Revenue Rights

- French Intervention and the Tussle Over the Deccan

- Maratha–Nizam Engagements in Tandulja and Udgir

- Treaty between the Nizam and the British, 1792

- The Nizams of Hyderabad Under British Paramountacy

- Local Administration

- The First War of Indepence, 1857

- Rohilla Raids and Suppression

- Bhalki Conspiracy of 1867

- Administrative Reform under Salar Jung I

- Land Tenure and Agriculture Under the Nizam’s Rule

- Language and Education

- Restrictions on Press and Assembly

- The National School of Lohara

- Arya Samaj

- Post-Independence

- Marathwada Mukti Sangram Din

- Killari Earthquake, 1993

- Sources

DHARASHIV

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Dharashiv (formerly known as Osmanabad district), situated within the Marathwada region of the Deccan, is a district of considerable antiquity and historical significance. Among the numerous archaeological localities therein, Ter, a small village, is particularly noteworthy. It was formerly a centre of much importance and appears to have had commercial significance in early historical periods. Excavations at the site have uncovered northern black polished ware, coins attributed to the Satavahana period, and terracotta figurines, indicating a settlement of long habitation and prosperity. Interestingly, certain finds suggest contact with foreign traders, most notably from the Roman world.

In subsequent centuries, Dharashiv passed through the hands of several powers. After the decline of Mughal authority in the Deccan, the district came under the rule of the Nizams of Hyderabad, wherein it acquired a particular status as part of the sarf-e-khaas, or the Nizam’s crown lands. In this arrangement, all local revenues were administered directly by the Nizam's household, and the expenditure of the district was met from the privy purse. In the modern period, Dharashiv played a noteworthy role in resisting the British administration and later figured prominently in the Marathwada Mukti Sangram, the movement that sought integration with the Indian Union.

Etymology

The district takes its name from the Dharashiv Caves, which are located within its limits and date to the 6th or 7th century CE. Multiple explanations exist regarding the origin of the name. One commonly accepted account attributes it to Shiv Raja, a local ruler from the nearby settlement of Ter, who is believed to have discovered the caves. According to this tradition, a stream once flowed near the site, and the name is thought to derive from a combination of Dhara (stream) and Shiv (the ruler’s name). Dr. Somnath Rode, who undertook a doctoral study of the site, supports this theory, suggesting that the naming followed the identification of a reliable water source in the area.

An alternative explanation is offered by Mahadevshastri Joshi, who posited that the name derives from two individuals, Dhara and Shiv, said to have been assigned as guards to the caves. Before the association with the caves, the region was referred to in local tradition as Nagesh Nagari.

In the 18th century, during the rule of the Nizam of Hyderabad, the district was renamed Osmanabad in 1904, after the 7th Nizam of Hyderabad, Mir Osman Ali Khan, who reigned from 1911 to 1948. On 26 February 2023, the Maharashtra government officially changed the district’s name back to Dharashiv.

Ancient Period

Rishi Kardam & the Legend of Tulja Bhavani

There are many legends set in a time of great antiquity in Dharashiv. Among them, the tale tied to the manifestation of Bhavani Devi at Tuljapur is of particular significance. According to one account, mentioned in the District Gazetteer (1972), a Rishi named Kardam once lived with his wife, Anubhuthi, and their young child near the banks of the Mandakini river. After Kardam's passing, Anubhuthi, left alone, is said to have begun a fierce penance, calling upon a divine force to protect her son. As she meditated, deep in the forested hills, a rakshas named Kukur appeared and began to torment her, seeking to disrupt her devotion.

It was then that the Devi is believed to have emerged, powerful and unyielding. She struck down the Rakshas and, at Anubhuthi’s request, chose to remain on the hill as a guardian and mother to all who sought her protection. From that moment on, she came to be known as the Bhavani of Tuljapur or Tulja Bhavani.

Another account, which also links the Devi to the site of the Tulja Bhavani Mandir, describes her encounter with a rakshas who had taken the form of a buffalo, Mahishasur. After defeating him, the Devi is believed to have taken shelter on Yamunachala hill, part of the Balaghat range, where the present-day Mandir in Tuljapur now stands.

Ter - a Trading Centre during the Satavahana Period

The early political history of Dharashiv district is difficult to reconstruct, as little is known about it. However, when considered within the broader territorial and administrative shifts of the Deccan and Marathwada region, a general outline can be drawn.

The earliest known signs of a political power in the region may be traced to the Maurya Empire, which, according to the revised district Gazetteer (1972), held sway over many parts of the Deccan region approximately between 185 BCE and 149 BCE. Ashoka’s Fifth and Thirteenth Rock Edicts make reference to local polities such as the Rashtrika-Petenikas and Bhoja-Petenikas, groups who are believed by scholars to have held control over territories extending to Pratisthana (modern Paithan) and possibly across parts of present-day Maharashtra.

Following the decline of the Mauryas and the subsequent Shunga dynasty, the region entered a period of fragmented rule until it came under the dominion of the Satavahanas, a dynasty whose influence extended across large swathes of the Deccan. It was under the Satavahana administration that the district, and particularly the settlement of Ter (which lies in the district), entered a phase of pronounced prosperity. In ancient times, what is now a quiet village was once a thriving trade center with links that extended as far as Rome.

In recent years, Ter has become an increasingly important site for archaeologists and historians. It has been mentioned in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea [1st-century Greco-Roman trade manual] as a major inland trading center alongside Pratisthana (historic city, modern-day Paithan in Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar district). Its role in early trade networks is described in the district Gazetteer (1972), where it is noted that: “Its antiquity can be traced as far back as the Puranas wherein it is referred to as Satyapuri and in the ancient period of our history as Tagarnagar.”

The rise of the Satavahana dynasty (early Deccan rulers, 1st century BCE–3rd century CE) contributed significantly to Ter’s development as a major trading center. The settlement is believed to have reached its peak of prosperity during this period, supported by expanding territorial control and increased commercial activity.

Situated along strategic inland trade routes, the settlement connected the Western Indian ports of Bharuch (Gujarat) and Sopara (Palghar district, Maharashtra) with interior markets and administrative centers like Pratisthana (present-day Paithan, Sambhaji Nagar, Maharashtra). Goods such as cotton, jowar (sorghum), and locally produced textiles were transported through Ter and formed part of a vast transregional exchange extending to the Mediterranean world. These goods formed part of a larger exchange network that connected South Asia with the Western world.

The evidence of Ter’s commercial and cultural importance has been uncovered through extensive archaeological efforts. Numerous coins from the Satavahana period, as well as inscriptions written in Brahmi script, have been found in the area, confirming Ter’s role as a key trade hub. Symbols of elephants and corn, found on some of these coins, hint at the importance of agriculture and animal trade during the time.

Many of the artifacts recovered from Ter are today housed in the K. Ramlingappa Lamture Government Museum (Ramling Appa Lamture Shasakiya Vastusangrahalay), which was established to preserve the antiquities and material culture of the ancient village. The museum exhibits include mirror handles, ceramic vessels, tools, and coins, offering a glimpse into a settlement that once stood as a node of commerce and culture in the ancient Deccan.

The Spread of Buddhism and the Fall of Ter

The development of Ter as a trading settlement during the Satavahana period coincided with the growth of religious activity in the region. Among the traditions represented during this time, Buddhism appears to have had a significant presence.

Buddhism had been spreading across the Deccan since at least the 3rd century BCE, aided by both the patronage of many Satavahana rulers and mercantile support. Excavations at Ter have revealed remains of structural stupas. These findings suggest the presence of an active monastic establishment and likely indicate that Ter served as both a residential and transit point for monks, especially those travelling between the western ports and interior cities.

Archaeological excavations at Ter have brought to light the remains of structural stupas, along with terracotta figurines, ritual objects, and pottery commonly linked to early Buddhist use. These finds suggest the existence of an active monastic establishment and point to Ter’s role as both a residential site for monks and a transit point on overland routes connecting the western ports to interior towns and administrative centers.

Another trace that connects Ter to its Buddhist past lies in its name. The origin of the name "Ter" is uncertain and has been the subject of multiple theories. One local theory proposes that the name Ter may have evolved from Ther, possibly referencing a Buddhist teacher or monastic title, especially given the numerous early Buddhist shrines and relics in the vicinity. While this theory remains unproven, it reflects the enduring cultural memory of the region’s Buddhist past.

Despite its former prominence, Ter began to lose its importance sometime after the 3rd century CE (which coincides with the decline of Satavahanas). The reasons for this decline are not fully understood. Local legends suggest episodes of flooding or natural disasters, while modern scholars have pointed to more structural causes such as the shifts in trade routes and the emergence of rival centers. What many scholars say, however, is that by the time new powers emerged in the western Deccan, Ter appears to have lost much of its former commercial and religious vitality.

The period following the Satavahanas saw the rise of the Abhira dynasty in parts of western Maharashtra. The revised district Gazetteer (1972) notes that the most significant source confirming Abhira rule is an inscription of Rajan Isvarasena, found in a cave at Nashik, which marks the beginning of the Kalachuri-Chedi era around 250 CE.

While no inscriptions or coins of the Abhiras have been discovered yet in Dharashiv district, their presence in neighbouring regions, including Nashik, Sambhaji Nagar, and parts of the Khandesh region and Gujarat, suggests that some level of Abhira influence or control may have extended into the district during this time. The nature of this presence, whether administrative or military, remains uncertain.

Following the decline of the Abhiras, political authority in the Deccan appears to have shifted toward the Vakataka dynasty, which rose to prominence in the early 4th century CE. Founded by Vindhyasakti I and later expanded by Pravarasena I, the Vakatakas established their base in Vidarbha, with capitals at Nandivardhana and later Pravarapura (identified with Nagpur and present-day Pavnar, near Wardha, respectively).

Their expansion into eastern Maharashtra and parts of the western Deccan suggests that the district may have come under their indirect control or influence during the 4th and 5th centuries CE. The Gazetteer notes that after 415 CE, the Vakatakas gradually superseded other smaller powers in the region, including the Traikutakas, who had replaced the Abhiras in some areas.

By the late 5th century CE, the Vakataka state had begun to weaken. According to the Gazetteer, the kingdom was invaded by Bhavadattavarman, a ruler of the Nal dynasty, though control of the region was eventually restored by the Vatsagulma branch of the Vakatakas, whose capital lay in Washim district.

Interestingly, traces of the presence of Buddhism appear again in the district during this period. On the outskirts of the present-day town of Dharashiv, a group of rock-cut caves, which are now known as the Dharashiv Leni, were excavated. Scholars generally date the initial excavation of the caves to the 5th century CE, though some suggest earlier origins likely during or shortly after the Satavahana period (circa 1st century BCE – 3rd century CE).

The earliest caves, Caves 1 to 3, contain Buddhist architectural features, including a chaityagriha, viharas, and a garbhagriha housing a seated image of Gautama Buddha in padmasana. These features have led many scholars to connect the site to a wider network of religious and monastic activity in the Deccan. The layout and carving style bear similarities to other cave complexes such as Ellora and Ajanta, suggesting that the site may have also served as a waypoint for traders, monks, and travellers moving through the region.

Additions or modifications to the caves are believed to have taken place during the Rashtrakuta period (8th to 10th century CE). The Rashtrakutas, who were major patrons of Jain and Hindu architecture, likely oversaw or permitted the reuse of the site. As a result, Jain and Brahmanical elements are also present in the later phases of the complex, reflecting a layered history of religious use.

Another aspect of note in connection with the caves is the figure of Shiv Raja, whose name is preserved much in oral tradition. As discussed earlier in relation to the site’s name, Shiv Raja is remembered as a ruler from Ter, associated with the creation of the caves. The name “Dharashiv” is believed by some to combine the words “Dhara” (stream) and “Shiv” (referring to the king), linked to a stream once said to have flowed near the site.

Interestingly, near the caves, a tamarind tree stands beside a raised platform bearing a vermilion-smeared murti of Maruti (Hanuman). Adjacent to it are three samadhis, which some locals identify as the resting places of Shiv Raja’s mother, sister, and wife.

Rashtrakutas and Jain Excavations at Dharashiv Leni

Following the decline of the Vakatakas in the early 6th century CE, new powers emerged in the western Deccan, among them the Chalukyas of Badami. Also referred to as the Early Chalukyas, they established rule over a broad region from c. 543 to 753 CE, during which time parts of what is now Dharashiv district likely fell within their extended zone of control.

The Rashtrakutas, who displaced the Chalukyas of Badami around c. 753 CE, became a major force in the Deccan for the next two centuries. Their influence extended into large parts of present-day Maharashtra and perhaps even parts of the present-day district.

It is during the 8th and 10th centuries CE that several architectural modifications are believed to have taken place at the Dharashiv Leni caves, located near the present-day town of Dharashiv. While the original excavation of the caves may date to an earlier time, scholars have suggested that later additions, including Jain and Brahmanical features, were carried out during the Rashtrakuta period.

Shilaharas and their Possible Connection to Ter

By the 8th century CE, the Shilahara dynasty emerged as a significant regional power in western India. The Shilaharas were a dynasty of Kanarese origin who ruled in western India from the 8th to the 13th century CE. There were three main branches: one ruled in North Konkan, another in South Konkan, and a third in the southern Maratha region, including parts of modern Kolhapur and Belgaum districts. They initially served as feudatories of the Rashtrakutas, before asserting greater autonomy in the centuries that followed.

Interestingly, in their inscriptions, the Shilaharas often mention that they came from a place called Tagara. This place has been identified in several ways, but the most widely accepted view today is that it refers to the town of Ter in present-day Dharashiv district. According to the Maharashtra State Gazetteers (Chapter 8: The Shilaharas of Western India), “The most plausible identification is with the village Ter in the Osmanabad [Dharashiv] district of the Marathwada Division of Maharashtra.”

There is no evidence that Ter was ever a Shilahara capital, and according to the Gazetteer, it seems instead that the name Tagara was used to give prestige to the family line. In some grants, the rulers are called “Tagarapura-var-adhisvara”, a phrase that means “the lords of the city of Tagara.” This suggests that by that time, Ter was still seen as a place of importance.

The name continued to carry importance into the 11th century, when local feudatories such as the Modhas of Samyana adopted similar titles. In the Cincani plates of Prince Vijjala, dated Saka 975 (1053 CE), the ruler refers to himself as “the lord of Tagarapura”, alongside other honorifics borrowed from the Shilaharas.

Chalukyas & the King Nal of Naldurg

After the decline of the Rashtrakutas in the late 10th century CE, power in the western Deccan passed into the hands of the Chalukyas of Kalyani, often referred to as the Later Chalukyas. They remained influential in the region for over a century, and an inscription found in the nearby Latur district suggests that this part of Marathwada was likely under their control.

Notably, one structure often associated with their presence is the Naldurg Fort, a large medieval stone fort located in Tuljapur taluka. The fort, situated along the Bori River, is considered one of the largest land forts in Maharashtra.

The origins of the fort are traditionally linked to King Nal, who is said to have ruled the region before the conquests of the Delhi Sultanate in the Deccan region. Local guides often claim that Nal built the fort after defeating the Vakataka dynasty (c. 250–500 CE). However, much of its early history remains unknown.

In the district Gazetteer (1972), an account by British officer Colonel Meadows Taylor, stationed in the district between 1853 and 1857, is noted, where he writes that:

“Nuldroog held a memorable place in local history. Before the Muslim invasion in the 14th century, it belonged to a local Rajah, who may have been a feudal vassal of the great Rajahs of the Chalukya dynasty, whose capital was Kalyani, about 40 miles away. However, I never could trace its history with certainty…”

The region came under the Badami Chalukyas (c. 543–753 CE) and later the Western Chalukyas, who maintained control until the arrival of the Bahmani Sultanate in the mid-14th century. During this period of early fortification, the site began to take shape as a military stronghold in the Deccan. The fort is notable for its extensive stone walls, moats, Indo-Islamic architecture, and strategic military role throughout the Deccan's medieval history.

Yadavas & Hemadpanthi Mandirs

Following the decline of Chalukya power in the western Deccan, the Yadavas of Devagiri emerged as the dominant regional authority by the closing years of the twelfth century CE. Formerly feudatories of the Western Chalukyas, they asserted independence around 1187 CE and established their capital at Devagiri (modern Daulatabad, Sambhaji Nagar). Their territory extended across many parts of the Deccan, and they maintained their rule until the early fourteenth century.

Their rule left behind notable architectural remains. Among these are Mandirs constructed in what has come to be known as the Hemadpanthi style, a form associated with Hemadri (Hemadpant), a minister at the Yadava court. This style is marked by the use of locally quarried black stone, precise dry masonry, and angular, star-like plans.

One such Mandir survives at Mankeshwar in the district, which lies on the banks of the Vishwakarma River. Built in the Hemadpanthi style, the structure is carved from a single block of black stone and follows a star-shaped layout. At the centre is a sabha mandap supported by four intricately carved pillars, featuring lotus motifs and images of Nataraj Shiv (cosmic dancer form of Shiv).

The Tulja Bhavani Mandir and the Kadamb Lineage

Another religious site of note during the Yadava period was the Tulja Bhavani Mandir, located at Tuljapur, on the slopes of the Balaghat range. The Mandir has long held an important place in the religious, cultural, and political landscape of the region and is one of the four major Shaktipeeths in Maharashtra. It is dedicated to Devi Bhavani, who is regarded as a fierce form of the Devi Durga and is deeply venerated across the region.

The Mandir is traditionally believed to have been constructed in the 12th century CE by a Maratha figure named Mahamandaleshwar Maraddev (Mahadev) Kadamb. Notably, it is still managed by the descendants of the Kadamb Bhope clan, who are entrusted with its upkeep. The site would go on to acquire greater significance, even political, in later centuries (see more below).

Sant Gora Kumbhar

Sant Gora Kumbhar, also known as Goroba, was a revered Hindu saint of the Bhakti movement and a prominent figure in the Varkari tradition of Maharashtra, India. A potter by profession and a devoted follower of Lord Vithal, he composed and sang numerous Abhangas (devotional hymns) alongside other saints of the movement.

Tradition holds that Gora Kumbhar lived in the village of Satyapuri—now called Goraba Ter—in the Dharashiv district of Maharashtra. He is believed to have been a contemporary of Sant Namdev and lived approximately between 1267 and 1317 CE. In his honor, a small temple bearing his name stands in his native village and continues to attract devotees and pilgrims.

Medieval Period

Rule of the Delhi Sultanate in the Deccan Region

After the Yadavas, the Khiljis (under the Delhi Sultanate) administered Osmanabad and its surrounding areas for a brief period. This changed in 1294 CE, when Alauddin Khilji, a commander under the Delhi Sultanate, invaded the Deccan and forced the Yadava ruler Ramachandra to pay tribute. Although the Yadavas continued to rule for some time under this arrangement, their independence gradually declined. By 1318 CE, their kingdom had been fully annexed into the Sultanate's territory.

After this annexation, Dharashiv came under the control of the Delhi Sultanate. The Sultanate divided its Deccan territories into four provinces, each governed by an official appointed from Delhi. These governors acted on behalf of the Sultan and were responsible for maintaining law and order, collecting revenue, and overseeing military matters.

The period of Sultanate rule in the Deccan was marked by some instability. Heavy taxation, often collected with force, placed great strain on the local population. Resentment against the governors grew, and in several areas, rebellions broke out. In an unusual move, some parts of the Deccan were briefly promised to the Mongol Empire during a period of political pressure from the north.

By the mid-14th century, central authority in Delhi had weakened, particularly after the troubled reign of Muhammad bin Tughlaq. This created an opening for local leaders to assert their independence. In 1347 CE, one of the Sultanate’s former military commanders, Hasan Gangu (later known as Alauddin Hasan Bahman Shah), declared himself ruler and established the Bahmani Sultanate. By 1351, most of the Deccan, including Dharashiv, had passed out of the Delhi Sultanate’s control.

Bahmani Rule and Administrative Reorganizations

The Bahmani Sultanate was the first independent Muslim kingdom in the Deccan. It was established in 1347 CE by Alauddin Hasan Bahman Shah, who, as noted earlier, was a former officer in the army of Muhammad bin Tughlaq. Some accounts claim he had once served as a court noble, while others describe him as having humble origins, possibly in the service of a Brahmin astrologer. Regardless of his background, Bahman Shah successfully consolidated control over large parts of the Deccan, including the area now known as the Dharashiv district.

To govern the newly formed kingdom, the Bahmani state was divided into four large provinces, or tarafs. Dharashiv was included in the Gulbarga province, which was named after the capital city of the Sultanate. The administration relied on provincial governors, who were responsible for local defence, tax collection, and maintaining order. During this period, several important military structures were built or reinforced in the region, most notably the forts at Paranda and Naldurg, both of which later became sites of strategic importance.

Despite these developments, many events took place which made life under Bahmani rule often difficult for the ordinary population. Heavy taxation remained a source of grievance, particularly during times of natural crisis. The region was struck by several devastating famines, including the Durgadevi famine (1396–1407 CE) and another in 1421–22 CE, following two consecutive years of failed rains. In response, the state offered limited relief: land was temporarily given rent-free, and grain was distributed to ease the burden on farmers and cavalry. Even so, many continued to suffer. A later famine, remembered locally as the Damaji Pant famine, further deepened rural distress.

In the early 15th century, as part of a wider administrative reform, the Bahmani rulers reorganised their provinces, expanding the number from four to eight. Dharashiv remained under the Ahsanabad (Hasnabad) division, centred around Gulbarga. Around this time, governance of the district was handed over to two officials: Zain Khan and Khvaja Jahan. The latter would go on to become a key figure in Dharashiv’s political history, especially in relation to Paranda fort, which served as his base of power.

Toward the end of the Bahmani rule, the kingdom came under increasing pressure from neighbouring states. The Sultanate of Gujarat, allied with the Vijayanagar Empire, attacked from the west and south. In one of these campaigns, they captured parts of the Dharashiv region, including the fort at Naldurg. These events signalled the beginning of the Bahmani kingdom’s fragmentation, leading to the rise of smaller, independent states that would dominate the Deccan in the 16th century.

Local Governance under Khvaja Jahan at Paranda

After the Bahmani Sultanate broke apart in the late 1400s, the Deccan region was ruled by three smaller kingdoms: the Nizam Shahis of Ahmadnagar, the Barid Shahis of Bidar, and the Adil Shahis of Bijapur. During this time, Dharashiv district was divided between these powers and often changed hands in battle.

One important figure in this period was Khvaja Jahan, who controlled Paranda and its surrounding areas. Although he had earlier served the Bahmani rulers, he gradually became a semi-independent governor. He ruled over five and a half districts from Paranda fort, which had become an important military and administrative centre in the region.

In 1490, after Malik Ahmad Nizam Shah declared the independence of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, the Bahmanis sent Khvaja Jahan to attack him. The Nizam Shahis fought back and won, with help from the Gujarat Sultanate. Khvaja Jahan withdrew and later joined the Nizam Shahi side. In return, he was allowed to keep control of Paranda.

In 1495, Khvaja Jahan fought alongside another Nizam Shahi officer named Dastur Dinar, but they were defeated. Even so, Khvaja Jahan remained on good terms with the Nizam Shahi rulers and continued to govern from Paranda. About ten years later, in 1504, the three major Deccan kingdoms went to war. Amir Barid, a ruler in Bidar, captured nearby Gunjoti (Umarga taluka, Dharashiv district), and Malik Ahmad Nizam Shah demanded that the Adil Shahis return Naldurg fort to him.

When Malik Ahmad died in 1510, the Adil Shahis used the opportunity to attack. Khvaja Jahan lost control of several districts, although he held on to Paranda. Control of nearby forts was also shifting. Ismail Adil Shah, still a minor, ruled Bijapur under the guidance of his regent Kamal Khan. Kamal Khan allied with Amir Barid I and divided the region: Naldurg and nearby forts went to Amir Barid, and other areas stayed under Kamal Khan’s control.

Despite these changes, Khvaja Jahan continued to rule Paranda for several years. At one point, he switched sides again, attacking Bijapur troops with Deccan cavalry and killing around 300 archers. In 1528, a joint invasion by the Nizam Shahis and Barid Shahis into Bijapur failed. Khvaja Jahan was captured and imprisoned, and Paranda was partially lost. After Khvaja Jahan’s capture in 1528 during a failed campaign against Bijapur, his political role diminished. By 1542, however, the Nizam Shahis had regained strength and gave some nearby districts back to Khvaja Jahan after a campaign in Solapur. In 1549, Burhan Nizam Shah again tried to attack Bijapur, this time with help from a Vijayanagar king. Ahmadnagar troops briefly captured Paranda fort before the gates could be shut.

In 1551, the Nizam Shahis strengthened ties with Khvaja Jahan by marrying a royal family member to his daughter. Paranda was finally brought fully under the Ahmadnagar Sultanate’s control. Around the same time, the Adil Shahis captured Naldurg and launched fresh attacks between Solapur and Paranda. As the rivalries between the Sultanate continued, Jahan’s position as a semi-autonomous ruler of the region, in many ways, remained significant throughout this tumultuous period.

Naldurg under Siege (1580-81)

By the 1580s, tensions between the Nizam Shahis of Ahmadnagar and the Adil Shahis of Bijapur had once again intensified. Around 1580, the Bijapuri forces launched an attack on Dharashiv but were pushed back. However, they succeeded in occupying Naldurg, where they stationed their troops, while the Ahmadnagar army remained positioned nearby.

In response, the Nizam Shahis captured Naldurg fort, briefly reclaiming it. Their hold on the fort, however, was short-lived. The Ahmadnagar forces soon withdrew, allowing Bijapur to regain control.

The following year, in 1581, the Nizam Shahis, now allied with the Qutb Shahis of Golconda, launched a joint campaign to take Naldurg once again. According to the Gazetteer (1909), the two armies surrounded the fort and called on its commander to surrender. When he refused, the walls were breached and the fort was attacked. Despite this effort, the operation failed, and the defenders successfully repelled the siege. The fort remained in Bijapuri hands.

Paranda and the Campaigns of Burhan Nizam Shah

In 1590, Burhan Nizam Shah II ascended the throne of Ahmadnagar. In 1594, he allied with Venkatadri, a ruler from Vijayanagar, and turned his attention toward Bijapur. His forces successfully captured Solapur and advanced toward Paranda, which, as illustrated above, was a strategically important town in Dharashiv district.

However, the Bijapuri forces retaliated with strength. Burhan’s army was defeated, forcing him to retreat. The loss marked a setback in the Sutanate’s efforts to reclaim territory in southern Dharashiv. Following Burhan’s retreat and death, his successor Ibrahim Nizam Shah ruled only briefly.

The Rise of Malik Ambar and Paranda as the New Capital

In 1600, the Mughal Empire, under Emperor Akbar, captured Ahmednagar (present-day Ahilyanagar), which was the capital of the Nizam Shahis. The death of Chand Bibi, the regent who had led the defence of the city, marked a turning point. However, resistance in the Deccan did not end with the fall of the capital.

In the aftermath, several Nizam Shahi nobles refused to submit to Mughal authority. Among them, Malik Ambar, an Abyssinian-born military commander and statesman, emerged as the dominant figure. He declared Murtaza Nizam Shah II, a child of the royal family, as the nominal ruler and took charge as the de facto head of state.

To reorganise the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, Malik Ambar shifted the capital to Paranda, a fortified town in Dharashiv district. From 1600 to 1607, Paranda served as the centre of their political and military resistance. During this period, Ambar reorganised the army, introduced a new land revenue system (regha), and built a mobile, efficient administration. Though the capital was later moved to Khadki (present-day Sambhaji Nagar) in 1607, Paranda remained a strategic centre well into the later 17th century.

Sustained Resistance and Mughal Annexation

Even after the capital shifted, Malik Ambar continued to direct resistance against the Mughal forces. His leadership delayed Mughal consolidation in the Deccan for nearly three decades. Dharashiv, with its forts at Paranda and Naldurg, remained a crucial zone of defence throughout this period.

In 1626, Malik Ambar died, and the Nizam Shahi dynasty weakened significantly. A year later, in 1627, a devastating famine struck the Deccan. With the rains failing and diseases spreading, Dharashiv district faced heavy depopulation and economic decline. These pressures hastened the collapse of local resistance.

By 1636, the Mughal Empire formally annexed the remaining Nizam Shahi territories. The Daulatabad Subah was created as part of a new four-province structure in the Deccan, which included Berar, Khandesh, and Telangana. Dharashiv was incorporated into Daulatabad Subah, and Mughal officers were posted to forts and administrative centres in the district.

Though the region was now officially part of the Mughal Empire, control over individual forts remained contested. Under the reign of Shah Jahan, a treaty was signed with the Adil Shahis of Bijapur, which forced them to surrender several forts, including Paranda. However, the Bijapuris did not fully withdraw, and Paranda continued to be held by local Bijapuri officers, leading to intermittent conflict.

Aurangzeb’s Campaign for Paranda Fort

After several years of tension, Aurangzeb attempted to secure Paranda fort from Bijapur through military and diplomatic pressure. He initially sent one of his subedars to capture the fort, prompting the Bijapuri forces to respond by mobilising at Naldurg. During this campaign, Mir Jumla, a senior Mughal commander, urged Aurangzeb to send his son to Paranda to press the claim more forcefully.

Aurangzeb also tried negotiating directly with the killedar (fort commander) of Paranda, urging him to surrender the fort. However, the killedar refused. When further Mughal troops were sent, Bijapuri resistance held firm, and Paranda remained under their control.

At this point, Mir Jumla, a senior Mughal officer, urged Aurangzeb to dispatch his son to press the claim on Paranda. Aurangzeb tried diplomatic means first; he persuaded the killedar (fort commander) of Paranda to surrender, but the offer was refused. Further Mughal troops were sent, but the Bijapuris held firm.

As political affairs in the Delhi court grew more complex, Aurangzeb negotiated peace, allowing the Adil Shah to retain Paranda and other territories. Still, internal rifts weakened the Bijapuri position. Ghalib Khan, the Bijapuri commander stationed at Paranda, received little support from his overlords and was pressured to surrender. Eventually, Mughal generals took command of the fort in 1673, but only after a prolonged and uncertain struggle.

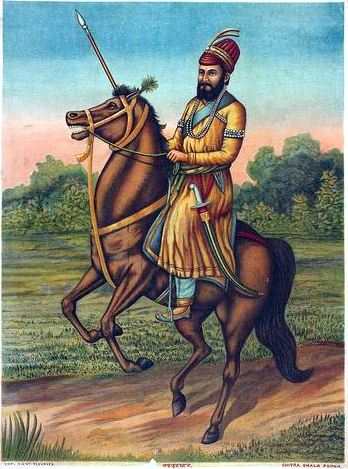

Shivaji and the Legend of the Bhavani Talwar

In the 1670s, Chhatrapati Shivaji, founder of the Maratha state, led a series of military campaigns across the Deccan. His efforts during this period were focused not only on expanding Maratha influence but also on recovering territory previously lost under treaties with the Mughals, especially following the Treaty of Purandar in 1665.

In 1666, a Mughal army advanced into Bhoom, a town in present-day Dharashiv district, where it remained stationed for nearly three months before continuing toward Sambhaji Nagar and Beed. The following year, Adil Shah entered into short-lived treaties with both Shivaji and the Mughals. But by 1670, tensions had reignited.

That April, Shivaji’s forces are said to have plundered more than 50 villages across Ahilyanagar, Junnar, and Paranda. At the time, Paranda Fort was still held by the Bijapuris, but its position, close to Maratha supply lines and contested frontiers, made it increasingly vulnerable.

Dharashiv held importance for the Marathas and Shivaji, not only for its forts and strategic location, but also for its religious significance. The region is home to the Tulja Bhavani Mandir in Tuljapur, dedicated to the Bhavani Devi, who was the kulswamini (family deity) of the Maratha rulers.

According to tradition, Shivaji received the Bhavani Talwar, a divine sword, from the Devi. This act is viewed as a blessing to support his efforts in establishing swarajya (self-rule) and facing military challenges. Over the years, the Bhavani Talwar came to represent Shivaji’s authority and the idea of divine support for his rule. As a result, the Mandir came to be seen as both a place of worship and a symbol of Maratha power.

Afzal Khan’s Campaign and the Attack on Tuljapur

Perhaps this significance is why Tuljapur also became the target of an attack by Shivaji’s rivals. In 1659, the Bijapur Sultanate launched a military campaign against Shivaji Bhonsale, who had begun consolidating territory across parts of the Deccan. The responsibility for this mission was given to Afzal Khan (Abdullah Bhatari), a senior noble and general in the Bijapur court. At the time, the Sultanate was facing both administrative and fiscal challenges and allocated a force of around 10,000 cavalry to accompany Afzal Khan.

Afzal Khan set out with the stated objective of bringing Shivaji to submission, by negotiation if possible, or by force. As part of this campaign, he marched through key locations in Dharashiv district, including Tuljapur, which was home to the Bhavani Mandir. During his passage, Afzal Khan ordered the desecration of the Mandir. The larger murti of the Devi was destroyed, though it is said that the pujaris managed to conceal the original murti in a water source.

From Tuljapur, Afzal Khan moved on toward Pandharpur, where further mandirs were damaged. Along the way, he issued letters to local deshmukhs, asking them to demonstrate allegiance to the Bijapur Sultanate. Afzal Khan’s objective was to force Shivaji into a meeting near Jawali, which lies in the present-day Satara district. Multiple letters were exchanged, and an envoy, Krushnaji Bhaskar, was sent to mediate the proposed terms of peace. Shivaji eventually agreed to the meeting, but military preparations were simultaneously put in place across the hill forts of the region, including Pratapgad.

The encounter between the two leaders on 10 November 1659 resulted in Afzal Khan’s death. His death was followed by Maratha attacks on the Bijapuri camp. This incident is considered a major turning point in the military engagements between Shivaji and the Bijapur Sultanate.

Capture of Naldurg and Mughal Military Gains

In 1673, the Mughal Empire launched an offensive in the region. At Umarga, Bijapuri general Bahlol Khan was defeated in battle, weakening Bijapur’s position in Dharashiv.

Three years later, in 1676, under direct orders from Aurangzeb, the Mughals intensified their southern campaign. Bahadur Khan, the Nawab of Balaghat, successfully captured Naldurg Fort, a vital military site. Other contingents moved quickly to secure the marketplace at Paranda. For a brief period, both Paranda and Naldurg were brought under Mughal command, though their control remained contested in the decades that followed.

The Battle Near Tuljapur, 1690

However, rather than dissolving, Maratha leadership reorganized under Rajaram, who escaped to Jinji in present-day Tamil Nadu. In the years that followed, Dharashiv district emerged as a key zone of conflict in the broader Maratha–Mughal struggle, with repeated clashes, raids, and military operations in and around Tuljapur, Bhoom, and Paranda.

In 1690, the area surrounding Tuljapur became the site of a lesser-known but notable military engagement. At the time, Rao Dalpat Bundela, a Mughal commander trusted by Aurangzeb, had been transferred from Naldurg Fort to oversee the road between Sambhaji Nagar and Tuljapur, a crucial stretch for Mughal troop movement and supply lines.

A battle soon broke out between Mughal and Maratha forces near Tuljapur. According to the District Gazetteer (1972), despite being vastly outnumbered, with the Mughals numbering around 800 and the Marathas estimated at 12,000, the Mughal detachment successfully repelled the Maratha offensive. At the time, Maratha forces were also active in the surrounding region, including Tembhurni, Naldurg, and Gunjoti.

Following this period of intensified conflict, Dharashiv was administratively divided into two districts: Paranda and Naldurg. Each became the headquarters of their respective territories and were incorporated into the Aurangabad and Bijapur Subahs of the Mughal Empire.

The Jagir of Bhoom

Among the notable territorial units of the region during this period was the jagir of Bhoom, which remained under Maratha control throughout the latter half of the 17th century. In the year 1717, Sambhaji II of Kolhapur conferred this estate upon Senakhaskhel Yashwantrao Thorat, a commander of considerable repute, in recognition of military service rendered to the Kolhapur State. Yashwantrao administered the estate until he died in 1719, during which time the foundations were laid for what would grow into one of the more substantial jagirs within the Maratha sphere.

In due course, the estate was elevated to the status of a saunsthan, enjoying a degree of internal autonomy under the suzerainty of the Maharaja of Satara. This status was formalised in the wake of the Treaty of Warna, which clarified territorial claims between the rival houses of Kolhapur and Satara. The Thorat family, recognized for their continuing loyalty and military utility, were further honored with the jagir of Walwa (which lies in present-day Sangli district), upon which the hereditary title of “Dinkarrao” was conferred.

Interestingly, in the 19th century, although Bhoom was formally absorbed into the dominions of the Nizam of Hyderabad, the Thorat family continued to exercise effective control over local administration. Under the Hyderabad State, they functioned as autonomous jagirdars, retaining hereditary authority and overseeing the internal management of the estate throughout the period of British paramountcy. The successors of the Bhoom Jagir are noted to be as follows.

- Shrimant Senakhaskhel Yashwantrao Thorat

- Shrimant Senakhaskhel Narayanrao Thorat

- Shrimant Senakhaskhel Dattajirao Thorat

- Shrimant Senakhaskhel Vijaysinh Thorat

- Shrimant Senakhaskhel Amarsinh Thorat

Osmanabad as Sarf-e-Khaas Territory under the Nizams

After the decline of Mughal authority in the Deccan, power passed into the hands of the Asaf Jahi dynasty, the Nizams of Hyderabad, who declared autonomy in 1724. What distinguished Dharashiv during this period was its inclusion in the Nizam’s sarf-e-khaas (crown lands). These territories were directly managed by the Nizam himself, and their revenue and administration were reserved for the royal household.

Battle of Palkhed and Maratha Revenue Rights

The early years of Nizam rule were marked by contests with the Marathas, who had been asserting their revenue rights across the Deccan region. In 1728, Peshwa Baji Rao I launched a swift campaign against Nizam-ul-Mulk, culminating in the Battle of Palkhed. The Marathas demanded the right to collect chauth and sardeshmukhi (customary taxes) from six subahs of the Deccan, among them Aurangabad, which then included Dharashiv.

The Nizam’s defeat at Palkhed forced him to recognize Maratha claims over revenue collection. Though the region remained nominally under the Nizam, the Marathas began exercising real influence, stationing troops, appointing local agents, and intervening in administration. This influence became more visible in 1732, when Baji Rao personally travelled to Latur (which lies near the Dharashiv district and was also a part of it for many centuries) for negotiations at Rohe Rameshwar.

French Intervention and the Tussle Over the Deccan

After the death of Nizam-ul-Mulk in 1748, the Nizam’s sons fought for the throne. One of his sons, Nasir, was backed by the British, and his other son, Salabat Jung, was helped by the French. Salabat Jung became the Nizam, but he was known to be a puppet emperor. The Deccan was mainly administered by a French general, De Bussy, who governed Pondicherry during the time. Interestingly, the Nizam fought with General Bussy to dismiss him from his position. However, the Nizam’s forces were defeated.

The Peshwas viewed the Nizam’s defeat as well as the rupture of the alliance between the Nizam and the French as an opportunity to gain control of the Deccan. When Bussy was away, the Peshwas waged a four-day battle against the Nizam and took control of the Deccan territory. This included giving up control of the Naldurg fort. In this way, the Marathas commanded control over some of the Nizam’s areas.

Maratha–Nizam Engagements in Tandulja and Udgir

Once the French were defeated by the English, Nizam Salabat Jung was left with a weak army and no alliances to support him. Again, the Marathas viewed this as a golden opportunity to capture more territory belonging to the Nizam.

In 1760, the Maratha army (consisting of 40,000 men) overpowered the Nizam’s army, which consisted of only 22,000 men. This battle took place at Tandulja, which now lies in the nearby Latur district. The fort of Udgir (which was a part of Dharashiv and a strategic geographical location for the Nizams; now a part of Latur) was surrounded by Marathas. The Nizams lost the battle and were forced to give up a lot of territory, and subsequently, the Naldurg and Udgir forts fell into the hands of the Marathas.

The Nizam’s fortunes briefly reversed after the Maratha defeat in the Third Battle of Panipat (1761). After the death of Salabat Jung, his younger brother took over. In 1761, the Marathas fought the Afghan army in the battle of Panipat and suffered defeat. Nizam Ali decided that this was the perfect time to reclaim lost territories from the Marathas. He fought against the Maratha army in 1761 and won control of the Udgir fort. However, in 1763, when the Nizam attacked Pune, the Marathas defeated him. This time, the Nizam had to give away even more territory.

Treaty between the Nizam and the British, 1792

During the Third Anglo-Mysore War, the Nizam, the Marathas, and the British joined forces against Tipu Sultan. The war ended in 1792 with Tipu’s defeat, but the alliance altered power dynamics in the Deccan.Notably, this alliance cemented the relationship between the Nizam and the British; however, the relationship between the Marathas and the Nizam worsened.

After the war ended, the Nizam and the British signed an agreement. According to the agreement, the British would provide the Nizam with 6,000 soldiers and money to maintain the Nizam’s army. In return, in 1800, the Nizam promised to help the British in times of conflict. Moreover, the Nizam also promised a considerable number of soldiers and horses to the service of the British. The Nizam also gave up previously held territories in the Deccan to the British, which included Dharashiv. The district briefly came under company rule and was later returned to the Nizam’s administration under a subsidiary alliance.

The Nizams of Hyderabad Under British Paramountacy

Under the Raichur Doab Treaty of 1853, Osmanabad was again transferred to British control. The British agreed to maintain 5,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry in the region. According to the treaty, the British paid for the maintenance of the forces, and the Nizam did not have to contribute anything to their maintenance. In 1860, however, the territory was restored to the Nizam of Hyderabad, after which it remained under princely administration.

Local Administration

By the early 20th century, the district was organized into six talukas: Osmanabad (Headquarters), Kalamb, Tuljapur, Ausa, Paranda, and Naldurg (later merged with Tuljapur). Two major parganas, Gunjoti and Lohara, and jagir estates like Bhoom and Wandewadi formed part of the landholding system. In 1905, reorganization merged Wasi into Kalamb and Naldurg into Tuljapur, leaving five talukas.

According to the 1909 Gazetteer, at the time, 89% of the population were Hindus in the district, with 84% speaking Marathi. Other spoken languages likely included Kannada, Telugu, and Urdu, due to their proximity to Karnataka and Telangana. The population in the district declined from 6,49,272 (1891) to 5,35,027 (1901) largely due to severe famines in 1897 and 1900.

The First War of Indepence, 1857

During the rising of 1857, when rebellion had spread across large parts of Northern India, the Hyderabad State remained loyal to the British under the administration of Prime Minister Salar Jung. However, despite the Nizam’s official position, signs of resistance still surfaced in different parts of the state, including Dharashiv district. In 1858, Hyderabad’s own contingent forces were deployed to the northern parts of the state to suppress these growing disturbances. It was during this time that a significant “conspiracy” came to light, which is said to have involved several local figures.

At the center was a man named Rang Rao (see more on him in Beed district), who is said to have been acting on the instructions of Nana Saheb, who was among the most prominent leaders of the 1857 uprising in the North. Rang Rao moved across present-day Maharashtra, including through Umarga in Dharashiv, carrying letters from Nana Saheb and attempting to gather support for the rebellion. He aimed to raise men, secure alliances, and open a southern front in the larger struggle.

He was arrested near Umarga before the plan could take shape. Letters found in his possession revealed a wider network of contacts and a deliberate attempt to spark unrest in the region. Several individuals were arrested and brought to trial. Rang Rao was sentenced to life in prison and sent to the Andaman Islands, where he died in 1860.

Rohilla Raids and Suppression

Around the same time, some parts of the district experienced raids by Rohillas, members of a Pashtun-origin community who had earlier established power in Rohilkhand (in present-day Uttar Pradesh). Following the collapse of the rebellion in the north, bands of Rohillas migrated southward, looting villages along their route.

In February 1859, a group of approximately 150 Rohillas looted the village of Nelingah (present-day Nilangaha, in Latur district, then part of Dharashiv). A combined force from the Hyderabad Contingent and British officers was sent in pursuit. Captain Murray (stationed at Udgir) and Captain Grant (at Gangakhed, Parbhani) led the operation, capturing the group near Udgir. Investigations revealed that the patels (village headmen) of Harali (which lies in present-day Dharashiv) had sheltered the Rohillas. Letters found in the village tied the incident to the larger conspiracy involving Safdar-ud-Daulah and other rebel sympathizers.

By the end of 1859, most signs of armed resistance in the region had been brought under control by the combined efforts of the British and the Nizam’s forces. As a gesture of recognition, a new treaty was signed in July 1860 (noted earlier). Through it, the districts of Raichur (now in Karnataka) and Dharashiv were returned to Hyderabad, and a loan of ₹50 lakhs owed to the British was formally cancelled.

Bhalki Conspiracy of 1867

Even so, traces of unrest remained. In 1867, nearly a decade after the uprising, the Bhalki Conspiracy unfolded, which is often seen as the last major attempt to revive rebellion in Hyderabad State. It was led by Ram Rav, also known as Jung Bahadur or Madhu Rav, who claimed to be a descendant of the Maratha royal family and took on the title of Chhatrapati of Satara.

Between 1866 and early 1867, Jung Bahadur travelled through parts of Dharashiv district, including Dharashiv town, Tuljapur, and Nilanga (then part of the district). He issued appointment letters (kaulnamas), gathered followers, and raised funds through informal promissory notes (hundis), all while speaking openly of his intent to overthrow British rule in the Deccan. His circle of supporters extended to Ausa and Latur (both also within Dharashiv at the time), where efforts were made to recruit men and collect weapons.

At one stage, he occupied a small fort at Ashti (in present-day Bidar district), hoisted a saffron flag, and declared it his base. Witness statements and letters recovered later from his associates showed plans to capture strategic towns such as Ausa, Udgir, and Naldurg. The documents also revealed appeals for military support sent to local landholders (patels and deshmukhs), some of whom responded with offers of men and money. Seals found on his papers bore the royal title “Chhatrapati.”

Eventually, Jung Bahadur and his associates were arrested near Bhalki. Their testimonies revealed a detailed and well-organized conspiracy, but the uprising was suppressed before it could begin. This event is widely viewed as the final echo of the 1857 rebellion in the region.

Administrative Reform under Salar Jung I

The conclusion of this period of disorder was followed by systematic administrative reform under Salar Jung I. In 1867, the zilebandi system was introduced, dividing Hyderabad State into five divisions and seventeen districts. Dharashiv was placed under the Gulbarga Division. Salaried officers were appointed at district and tahsildar levels, and departments such as judiciary, education, revenue, and public works were reorganized.

Land Tenure and Agriculture Under the Nizam’s Rule

During this time, landholding in the district was regulated by the Ryotwari system. It was through the 1883 Land Settlement that British-administered reforms were later implemented to standardize land tenure, taxation, and agricultural productivity. The British government, under the Nizam of Hyderabad’s rule, conducted the settlement to improve revenue collection while encouraging efficient land use among tenant farmers (ryots).

In the district during the early 20th century, land tenure was primarily divided into Khalsa (Crown Land), which was directly administered by the government, and Jagir (Estates), granted to landlords and nobles who collected revenue from peasants. According to the Gazetteer (1909), out of the 2,627 square miles of Khalsa and Crown lands, 1,813 square miles were under cultivation, though only 96 square miles were irrigated, making agriculture heavily dependent on rainfall.

The region’s location in the Deccan Trap zone influenced its soil composition. Black soil predominated in talukas such as Osmanabad, Kalamb, Wasi, and Paranda and was well-suited for rabi crops like wheat and pulses. In other parts of the district, red and sandy soils supported kharif crops, mainly jowar, which was the most widely cultivated crop, accounting for around 70% of the sown area. Other crops included bajra, rice, cotton, and limited areas of sugarcane.

Soils were locally categorized as:

- Musat, a mix of red and white soil, is considered better suited for wheat and cotton.

- Bhanda, a coarser soil used mainly for grazing or low-yield crops.

The 1883 British land settlement, in many ways, significantly impacted farming practices by restricting land expansion and encouraging tenant farmers (ryots) to maximize yield through improved techniques. The Kunbis (Marathas) were the primary landowners, and while agriculture employed most of the population, the lack of irrigation and unpredictable rainfall made farming challenging. Despite these difficulties, farmers adapted to the terrain, ensuring that Dharashiv remained an essential agricultural district within Hyderabad State.

Language and Education

In 1884, Urdu replaced Persian as the official court language in the Hyderabad State. In the schools of the region, including those in present-day Dharashiv district, Urdu was introduced into the curriculum from Standard V. Students who failed the Urdu examination were required to repeat the academic year. Naitik Shiksha (moral instruction) was compulsory for all pupils, while Dharmik Shikshan (religious instruction) was compulsory for Muslim students.

Several educational institutions were established across the state during this time, particularly in major urban centers. These included the Hyderabad Medical College (1844), the Engineering College (1870), and the Nizam Vidyalaya (1887). Though located outside the present-day boundaries of Dharashiv district, these institutions likely offered opportunities for residents of the region to pursue higher education.

Within Dharashiv, educational development was concentrated primarily at the primary and secondary levels. The Imperial Gazetteer (1909) notes that in 1903, the district had 44 public educational institutions: 12 operated by the state and 32 managed by local boards. It should be noted that records concerning privately managed schools are not included here, and the figures pertain to the district as it was then constituted, encompassing both present-day Dharashiv and Latur.

Restrictions on Press and Assembly

During the same period, the Hyderabad government issued a circular regulating the press. Editors were instructed not to publish criticism of the Nizam or his officials. According to the district Gazetteer (1972), the Urdu newspaper Soukat-ul-Islam refused to comply with this directive and was subsequently shut down.

By the 1930s, several nationalist and religious reform movements began to emerge within the Hyderabad State, and new restrictions were imposed along with this. The Arya Samaj, which had established itself in Hyderabad in 1892, greatly expanded its educational and social presence across the region during this time. Although initially religious and reform-oriented, its activities increasingly came under scrutiny by the Nizam’s government, especially as it became involved in political protests and campaigns challenging the administration.

Consequently, in 1934, the Hyderabad administration introduced additional restrictions targeting educational and cultural gatherings, banning institutions such as vyayamshalas (gymnasiums), satsangs, and pravachans. These venues were perceived by the authorities as potential sites for political mobilisation or dissent.

The National School of Lohara

In 1921, amid this atmosphere, a National School was established at Hipparga (Rava) in Lohara taluka of the district. The school was founded by Venkatrao Deshmukh and Anantrao Kulkarni, with the support of Vishwanath Honalkar and Anandrao Patil. It operated outside the state’s educational system and drew attention for its independent methods and affiliations. From its early years, it was associated with ideas of national self-rule and quiet opposition to the Hyderabad State government.

Notably, several prominent figures became closely associated with the school in its later years. In 1923, Swami Ramanand Tirth joined as principal. Under his leadership, the institution expanded in both size and influence. By 1924, its activities had drawn the attention of both the Hyderabad administration and British authorities. A police post was established nearby, and surveillance increased.Despite these pressures, the teaching staff continued to promote ideas of self-rule and resistance to state authority.

By 1941, the school was hosting an annual gathering (Snehsammelan), with well-known guests such as the writer V.S. Khandekar invited to speak. In the years that followed, political tensions deepened. It is said that school administrators were harassed and required to report regularly to local authorities, while teachers were also subjected to scrutiny. The emergence of the Razakar militia, along with a local outbreak of plague, further contributed to instability in the region. The school eventually closed in 1946. Years later, a new institution, named Swami Ramanand Tirth Vidyalaya, was established at the same site in 1986.

Arya Samaj

In the mid-20th century, the influence of Arya Samaj spread across the region, including to Gunjoti in Umarga. The organization took a firm stance against religious conversions and expressed concern over the treatment of Hindus under the Nizam’s rule. Arya Samaj also opposed the push for the formation of a separate state, which became a major point of political debate at the time. These ideological differences contributed to rising tensions and frequent clashes between the Arya Samaj and the Nizam’s administration.

During these years, the Marathwada Mukti Ladai (Marathwada Liberation Movement) emerged as a broader struggle involving various groups, including Arya Samaj, in opposition to the Razakars, a volunteer force aligned with the Nizam’s regime.

Post-Independence

Marathwada Mukti Sangram Din

At the time of India’s independence in August 1947, Dharashiv district, along with the rest of Marathwada, remained under the rule of the Nizam of Hyderabad and did not immediately join the Indian Union. It was only after “Operation Polo”, the Indian military action to integrate Hyderabad State, that the region was merged with the rest of the country. The formal accession took place on 17 September 1948, thirteen months after India’s independence. This date is now observed annually across the region as Marathwada Mukti Sangram Din (Marathwada Liberation Day).

Following the merger, Dharashiv became part of the Bombay Province. Subsequently, with the passage of the Bombay Reorganisation Act, 1960, the Bombay State was divided, and Maharashtra and Gujarat were formed as separate linguistic states. Dharashiv, then still officially known as Osmanabad, was included in Maharashtra. At the time, the district also encompassed what is now Latur district, which was carved out later in 1982.

Killari Earthquake, 1993

On 30 September 1993, a 6.2 magnitude earthquake struck and devastated the district and its adjoining areas. The earthquake occurred in the early hours of the morning and destroyed more than 50 villages in the region. The Umarga taluka in the district is said to have faced the most devastation.

The earthquake caused widespread damage; according to official estimates, at least 10,000 people lost their lives, and over 30,000 were injured. In several parts of Dharashiv, especially in rural areas, physical traces of the damage remain visible even today.

The cause of the earthquake has been the subject of speculation. Some observers have linked it to the construction of a reservoir on the Terna River. Relief and rehabilitation efforts were carried out with assistance from both state and central governments, as well as international agencies. The World Bank provided significant financial support toward reconstruction, and numerous villages were rebuilt under planned resettlement schemes.

Sources

Akshardhool Stories. The Ancient Trade Hub of Tagar – Part I. Akshardhool Stories.https://akshardhoolstories.blogspot.com/p/th…

Azhar Mallick and Mohd Alfaz Ali. 2025. “Marathi history shouldn’t forget Malik Amber, the Muslim leader who united Deccan forces against Mughals.”The Indian Express.https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/co…

Chavan, A. 2018. The Goddess Who Went to Nepal. Live History India.https://www.livehistoryindia.com/

Dhaval Kulkarni. 2018. DNA Exclusive: Khichdi Was Around Even 2,000 Years Ago, Says Study. DNA India.https://www.dnaindia.com/india/report-dna-ex…

Durgbharari. Naldurg. Durgbharari.https://durgbharari.in/naldurg/

Imperial Gazetteer Of India Provincial Series Hyderabad State. 1909. Superintendent Of Government Printing, Calcutta.https://www.irfca.org/docs/history/hyderabad…

L.G. Rajwade ; G.A. Sharma; P. Setu, Madhava Rao et al. eds. (1972), Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Osmanabad District. Govt. Press, Bombay.

Lakshmi Subramanian. 2021."On the History Trail: Wagh Nakha and the Battle of Pratapgad."Sahasa.https://sahasa.in/2021/03/19/on-the-history-…

Lokmat. 2021."Throwing Dust in Eyes: Nizam National School Created Revolutionary." Lokmat. https://www.lokmat.com/dharashiv/throwing-du…

O’Royal Archives. "Bhoom."O’Royal Archives. https://oroyalarchives.com/bhoom/

Swati Goel Sharma and Mayur Bhonsale. 2023.The Mother and the Sword: A Visit to Tulja Bhavani Temple in Maharashtra. Swarajya.https://swarajyamag.com/culture/the-mother-a…

ThePrint. 2022. Dharashiv: New Name for Osmanabad Dates Back to Eighth Century, Expert. ThePrint.https://theprint.in/india/dharashiv-new-name…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.