Contents

- Ancient Period

- Remains of Dinosaurs, Fossils, and Early Human Life at Wadadham

- Megalithic Burials & the Gond Madias

- Associations with the Mahabharat

- Early Dynasties in Eastern Vidarbha and the Satavahana-Era Settlement at Mulchera

- Vairagad Fort and Its Earliest Epigraphic Reference

- The Mana Dynasty and Fortification of Vairagad (7th – 10th Century CE)

- Yadava Dynasty & Vairagad

- Rise of the Gond Kingdom

- Medieval Period

- Transition of Gond Control in Eastern Territories

- Documentation in the Ain-I-Akbari

- The Legend of Puram Sah and the Fall of Tipagad

- General Harachandra & his Religious Patronage

- Late Gond Period and the Role of Rani Hirai

- Maratha Incursions into Vidarbha

- Raghunath Singh’s Rebellion & the Fall of the Chanda Kingdom

- Under the Rule of the Bhosales of Nagpur

- Rise of the British & the End of Maratha Control

- Colonial Period

- The First War of Independence, 1857

- Early Nationalist Activity and the Formation of the Chandrapur District Association

- Post-Independence

- Red Corridor & Naxalite Movement

- Social Developments & Community-Based Programs

- SEARCH (Society for Education, Action, and Research in Community Health)

- Mendha Lekha & the Forest Rights Act

- Sources

GADCHIROLI

History

Last updated on 11 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Gadchiroli district, located in the eastern part of the Vidarbha region, has a rich and layered history. Fascinatingly, one of the earliest records of its history dates back to the Mesozoic Era, commonly known as the “Age of Dinosaurs,” which makes the district unique in many ways. Archaeological evidence also indicates human habitation in the area as far back as the Early Stone Age (5,00,000 BCE – 10,000 BCE).

The district was once part of the Gond kingdom, with the present-day town of Gadchiroli marking its northern boundary. Interestingly, the district's name might be linked to this historical background. It is believed to originate from the words ‘Gad’ and ‘Chiroli', where Gad means fort and Chiroli likely comes from Chirodi, a thorny shrub common in the region; this could possibly reflect its position along the outer edge of the Gond kingdom. The region came under Maratha control in 1751, when Raghuji Bhosale of Nagpur expanded his rule into this area. After Nagpur was annexed by the British in 1853, it fell under colonial administration and was part of Chandrapur district. Gadchiroli stayed within Chandrapur district until 1982, when it was officially established as a separate district.

Ancient Period

Throughout history, the region that now forms the Gadchiroli district has been under the influence of various political and cultural powers. Little is currently known about its early history; however, archaeological remains and scattered references in literature offer some insights into the region’s past. These are better understood when placed in the context of Chandrapur and the eastern Vidarbha region, to which Gadchiroli has long been linked politically, administratively, and culturally.

Remains of Dinosaurs, Fossils, and Early Human Life at Wadadham

Wadadham is a small village that lies in the Sironcha taluka of Gadchiroli district. One of the earliest traces of life in Gadchiroli and perhaps even in the wider region of India can be tied to this place. The village is home to Maharashtra’s first fossil park and holds considerable geological and paleontological importance.

It lies within the Godavari-Pranhita river system, beneath which researchers have identified a fossilized forest bed, believed to date to the Mesozoic Era. Some of the fossilized trees found here include types that are now extinct, like Glossopteris and Dadoxylon. The dinosaurs that lived in these forests include sauropod species such as Barapasaurus and Kotasaurus. Fossils of ancient fish have also been found, showing that this region was once home to a rich and diverse ecological environment.

One of the most important discoveries at the site came in 1959, when a nearly complete dinosaur skeleton was found near the Godavari basin. Since then, more fossil sites have been identified and notably, a total of 24 in the Sironcha region alone. What makes Wadadham especially rare, as many paleontologists point out, is that fossils of both plants and animals from the same period have been found together and are well-preserved.

In recent years, stone tools attributed to the Paleolithic period (c. 5,00,000 – 10,000 BCE) have also been found in the vicinity, suggesting that early human populations inhabited or passed through the region long after the extinction of the dinosaur fauna. These findings place Wadadham among the few sites in central India where both paleontological and archaeological remains are found in close proximity.

Megalithic Burials & the Gond Madias

Another trace of Gadchiroli’s past comes from the megalithic monuments found in different parts of the district. These are large stone structures built in various forms, such as dolmens (stone slab tombs), menhirs (standing stones), and cromlechs (stone circles with central stones) which are typically associated with burial or memorial traditions.

Many scholars, such as Ganesh Halkare (2005-6), have pointed out that “the eastern fringe of Vidarbha [where Gadchiroli lies]” is home to a concentration of many “ancient megalithic monuments.” Many of these sites are believed to date back to the Iron Age, roughly between 1500 BCE and 200 BCE. Gilgaon village in Chamorshi, and Arsoda in Gadchiroli district are home to some of these sites.

Aside from the fact that these monuments provide valuable insights into the social and cultural life of communities that inhabited the region thousands of years ago, what makes them even more interesting is that some of these practices have not disappeared. Halkare (2005-6) notes that the Gond Madia community, who make up a considerable demographic in Gadchiroli, maintain the tradition of raising memorial stones for the dead. These stones, called Kalbanda and said to echo the construction of ancient menhirs, are placed upright in memory of deceased individuals and often arranged in family groups.

Excavations at ancient megalithic sites in Gadchiroli have also revealed that objects like earthen pots, tools, ornaments, and weapons would be buried with the dead . Notably, similar customs exist among the Madia community today. For instance, it is said that a sickle is buried with a woman as part of the funeral custom. The resemblance between ancient and current customs has drawn the attention of many researchers, who find this continuity of tradition very striking.

Associations with the Mahabharat

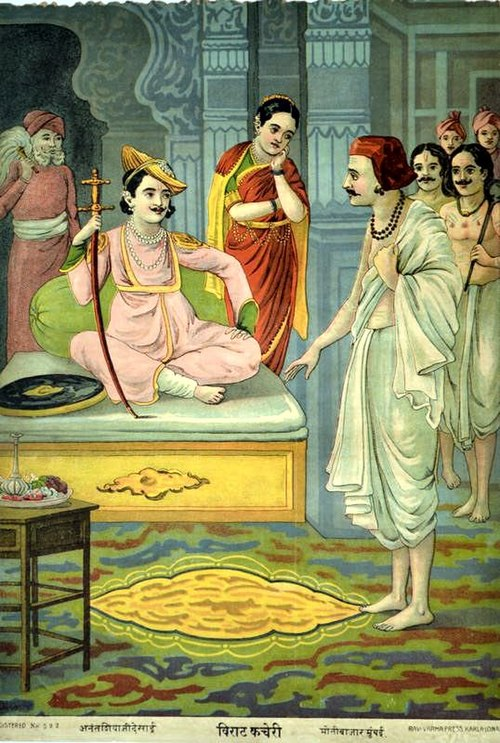

Several places in the present-day Gadchiroli district are locally believed to have associations with events described in the ancient Indian epic, the Mahabharat. Among these, the town of Vairagad is prominent. According to the Chandrapur district Gazetteer (1973), Vairagad is traditionally believed to have been founded “in the Dvapara Yuga by a king of the family of the moon, who called it Wairdgad after his own name Vairocan.”

This town is identified by some with Viratnagari, the city where the Pandavas are said to have lived during the thirteenth year of their exile. Local belief further holds that the region was once ruled by King Virata, the ruler of the Matsya Kingdom, who is mentioned in the epic and is associated with the Vedic period. (The historical significance of Vairagad within the district is considerable and is discussed in greater detail in subsequent sections).

Another site associated with the epic is the location of the Lakshagriha, or “House of Lacquer”, which was, in the epic, constructed to entrap the Pandavas by burning them alive. While various locations across India claim this site such as Barnava in Uttar Pradesh, local tradition also places it within the Gadchiroli district.

Early Dynasties in Eastern Vidarbha and the Satavahana-Era Settlement at Mulchera

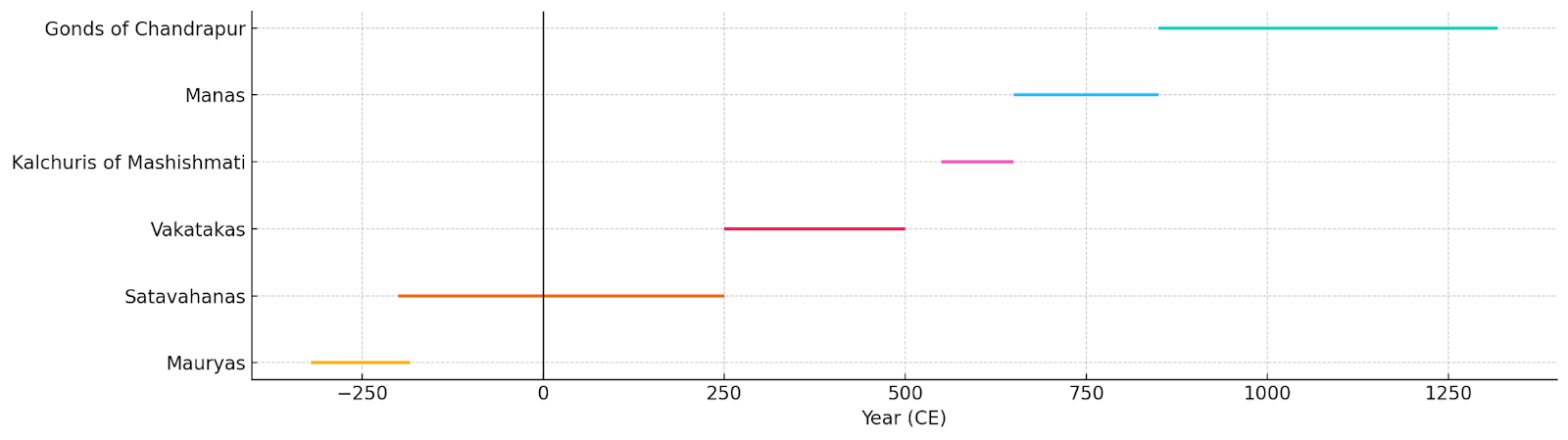

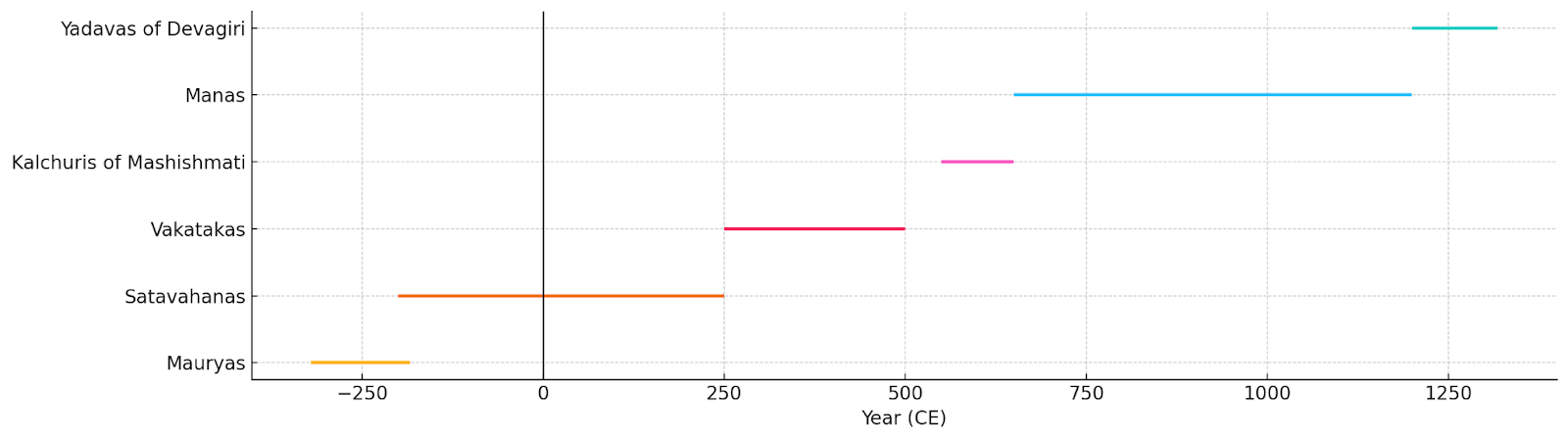

The earliest known political power to hold much influence and power over the Eastern Vidarbha region ( where the present-day Gadchiroli lies) was the Maurya Empire, around the 3rd century BCE. Their influence extended across large parts of the Indian subcontinent, including Vidarbha. With the decline of Mauryan control, the Shunga dynasty came to power in the region around 184 BCE, though for a comparatively brief period.

By 200 BCE, control passed to the Satavahana dynasty, whose rule over Vidarbha continued for nearly four centuries. Under the Satavahanas, the region witnessed significant developments in trade, religion, and urban settlement.

In Gadchiroli district, archaeological evidence of Satavahana-era occupation was uncovered at Mulchera, where excavations by the Archaeological Survey of India revealed structural and material remains. The ASI report (1988-89), on the excavation, notes:

“Stamped red ware, plain red ware and black ware, iron nails, roof tiles, a coin bearing letters in Brahmi characters and copper objects used in worship were found during the course of excavation. The structure seemed to be a temple built during the late Satavahana period which continued to be used in early Vakataka period.”

This discovery points to continuous habitation of the area in the late Satavahana period and into the early Vakataka phase, indicating that the region formed part of an active cultural and religious landscape during this time.

Vairagad Fort and Its Earliest Epigraphic Reference

As mentioned above, Vairagad Fort holds enduring significance in the historical narrative of Gadchiroli district. While the site is regarded as ancient in local tradition, its earliest known mention appears in the Hathigumpha inscription, located near Bhubaneshwar (Odisha) and dated to the 2nd century BCE.

The inscription records the military campaigns of King Kharavela of the Mahameghavahana dynasty of Kalinga, who is said to have advanced as far as the Krishna and Venna rivers, and to have married Princess Ghusita of Vairagad. This early reference suggests that Vairagad might have been a political centre at the time.

Vairagad would go on to assume further importance in the region’s history during the rule of the Mana and Gond dynasties (which will be discussed in the following sections).

The Mana Dynasty and Fortification of Vairagad (7th – 10th Century CE)

In the later half of the 3rd century, the Vakatakas ruled over Vidarbha for over 250 years. After the decline of their authority, power in this part of the Deccan plateau shifted to a dynasty known as the Kalachuris of Mahishmati around 550 CE.

The Kalachuris, whose capital was located in what is now Maheshwar town in present-day Madhya Pradesh, extended their rule into parts of present-day Maharashtra, including areas west of Vidarbha. However, by the 7th century CE, the Kalachuris’ influence here started fading, creating conditions that allowed local powers to emerge.

According to the Chandrapur district Gazetteer (1909), the second half of the 7th century saw the rise of the Mana dynasty, an indigenous political formation that gained prominence in the region now encompassing the districts of Chandrapur and Gadchiroli. The Mana rulers established control over these areas and governed them for a significant duration. The Gazetteer (1909) estimates their rule to have lasted from approximately 650 CE to 850 CE.

Alternative scholarly perspectives, however, suggest a longer period of Mana authority. For example, the Indian historian Shashishekhar Gopal Deogaonkar proposes that the dynasty remained in power until around 915 CE. During their reign, the Mana rulers undertook the construction and fortification of settlements, most notably at the site of present-day Vairagad. This location served as a key administrative and possibly military center, and its defensive structures are attributed to the efforts of Mana rulers.

Accounts of the dynasty’s decline vary. The colonial district Gazetteer (1909) attributes the end of Mana rule to Bhim Ballal, who is considered the founder of the Gond dynasty in the region. According to this version, Bhim Ballal overthrew the last Mana king and established Gond authority. Supporting this narrative is a genealogical record compiled by Major Lucie Smith, a British settlement officer in 1865. Drawing on local oral traditions, Smith’s record suggests that the Gond rulers governed continuously from the 9th century to the 18th century. However, the dating in his account has been questioned over time. Notably, the same 1909 Gazetteer that included Smith’s list also critiqued its accuracy, pointing out inconsistencies—particularly in the dates of key rulers. For example, Smith placed the reign of Khandkiya Ballal Shah between 1242 and 1282 CE, but inscriptional evidence cited in the Gazetteer revises this to 1437–1462 CE.

The revised Gazetteer (1972) supports the critiques and changes, however it also challenges the earlier timeline. This later version asserts that the Mana dynasty continued to rule until the 13th century CE and was eventually defeated not by the Gond rulers, but by the Yadava dynasty who were based in Devagiri. Thus, there exist two conflicting historical timelines regarding the duration and end of the Mana dynasty.

Yadava Dynasty & Vairagad

Archaeological and inscriptional evidence indicate that East Vidarbha, encompassing Gadchiroli and Chandrapur, was likely under the dominion of the Yadavas during the 13th century. Notably, inscriptions from the reign of Ramachandra, the last known ruling king of the Yadava dynasty were discovered in the contemporary towns of Ramtek (Nagpur district) and Lanji (Madhya Pradesh). They suggest the extension of Yadava influence into the eastern territories of Vidarbha and their possible influence over Gadchiroli.

Additionally, a 1939 report published in Epigraphica Indica by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) refers to a site called Vajrakara, identified as present-day Vairagad Fort. It records that Ramachandra deposed the ruler of Vajrakara, pointing to Yadava influence over the fort and surrounding areas.

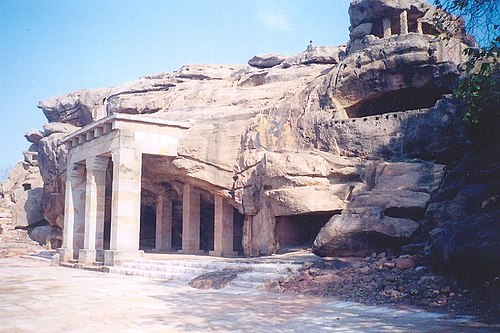

Another possible expression of Yadava influence in the region is the Markanda Deo Mandir, also known as Markandeshwar, located in the Chamorshi taluka of Gadchiroli district. Built between the 8th and 13th centuries CE, the Mandir is constructed in the Hemadpanthi architectural style. This distinctive style flourished under the Yadavas and is attributed to Hemadri Pandit (also called Hemadpant) who was a respected scholar and minister in their court.

The Mandir complex is not only significant for its architecture but also for its association with spiritual and religious figures. It is named after the Rishi Markandeya Maharshi, who, according to local legend, performed penance at this very site on the banks of the Wainganga River.

Rise of the Gond Kingdom

As discussed above, historical accounts differ on the precise timeline of Gond rule in Chandrapur. Still, according to later sources, the establishment of the Gond kingdom is closely linked to Sirpur, a village in present-day Chimur taluka of Chandrapur district. The revised district gazetteer places the foundation of the kingdom around 1320 CE, under the leadership of Bhim Ballal Singh. From this early nucleus, Gond influence extended steadily across eastern Vidarbha, encompassing areas that now form the Gadchiroli district.

Medieval Period

The medieval history of Gadchiroli district is closely tied to the fortunes of the Gond kingdom of Chandrapur. While the political centre of the region lay in present-day Chandrapur, several key developments directly shaped the history of Gadchiroli.

Transition of Gond Control in Eastern Territories

Among the earliest significant figures in the Gond Kingdom was Surja Ballal Singh, the ninth Gond ruler, known for his resistance against a military force dispatched by the Delhi Sultanate. His act of sheltering the daughter of Rajput chief Mohan Singh earned him the honorific “Ser Sah,” a title that would be adopted by subsequent Gond monarchs as a mark of valor and continuity.

Following the death of Surja Ballal Sah, the Gond kingdom passed into the hands of his son, Khandkya Ballal Sah, who is traditionally credited with founding the city of Chandrapur and initiating the construction of the Chandrapur Fort. The relevance of Chandrapur’s events to the Gadchiroli region becomes particularly notable from the reign of the 12th Gond Kings, Bhuma and Lokba, who are recorded to have jointly ruled.

According to the Chandrapur district Gazetteer (1909), a portion of the eastern territories was relinquished to the chief of Amravati in exchange for a gift of high value. It is believed that during this time, control over Vairagad Fort (mentioned above), situated in the present-day Gadchiroli, may have passed out of Gond hands.

Documentation in the Ain-I-Akbari

Further clarification on Gond territorial expansion in Gadchiroli is found in the Ain-i-Akbari, an important administrative text from the reign of Emperor Akbar. This source references Babji Ballal Sah, the 11th ruler of the Gond dynasty, whose reign was placed by the Chandrapur district Gazetteer (1909) between 1570 CE and 1595 CE.

According to the Ain-i-Akbari, Babji Ballal Sah regained control of the Vairagad Fort during his reign, with assistance from Puram Sah, a local ruler based in Tipagad (Gadchiroli district), who acknowledged Gond authority by paying tribute. This account suggests that by the latter half of the 16th century, Gadchiroli had once again come under the administrative reach of the Gond kingdom.

It is important to note that while many regional powers in Vidarbha had by this time entered into tributary relations with the Delhi Sultanate, the Gond polity maintained a degree of independence during much of this period. However, Babji Ballal Sah eventually entered a tributary relationship with Akbar, indicating the growing influence of the Mughals on the political and economic structures of the region.

The Legend of Puram Sah and the Fall of Tipagad

A notable episode in the early history of Gadchiroli centers on Puram Sah, the ruler of Tipagad, whose role in the region gained significance during the late 16th century. Following the Gond conquest of the Vairagad Fort, which as mentioned above was achieved with the support of Puram Sah, Ballal Sah is said to have entrusted him with its administration. As Puram’s authority expanded, his growing influence is believed to have provoked opposition among several contemporary chiefs, particularly in the Chhattisgarh region.

This tension culminated in a conflict at Kotgal, located in present-day Gadchiroli taluka. During the battle, a sandal adorned with embroidery is said to have slipped from Puram Sah. A soldier from the opposing Chhattisgarh side retrieved the sandal and presented it to the queen, inadvertently sparking a tragic misunderstanding. Mistaking the sandal as proof of Puram Sah’s death, the queen is believed to have taken her own life by drowning in a nearby lake.

Unaware of these events, Puram Sah returned victorious from the battlefield. On learning of the queen’s fate, he is said to have entered the same lake in grief. According to local accounts, this sequence of events led to the gradual decline of Tipagad, which eventually became deserted.

General Harachandra & his Religious Patronage

Following the demise of Puram Sah, the administration of Vairagad Fort passed into the hands of General Harachandra. His tenure is associated with the construction of several religious structures across Gadchiroli. These included seven Shiv Mandirs namely the Bhandareswar, Nandikeswar, Pataleshwar, Dubaleshwar, Akaleshwar, Rameshwar, and Mahabajeswar Mandirs; of which the Bhandareswar Mandir at Vairagad still stands today.

In addition, he is credited with building mandirs in and around the area, including the Shiv Mandir at present-day Armori.

Late Gond Period and the Role of Rani Hirai

Following the reigns of Dhundya Ram Sah and Krishna Sah, both of whom left little documentary trace with regard to Gadchiroli, the throne passed to Bir Sah. His queen, Rani Hirai, notably, during his reign, emerged as a pivotal figure in the cultural life of the region. It is mentioned in the Gazetteer (1909) that:

“The seventeenth century was an age of faith. Construction of a mandir, a tank or well, a rest house or any building of public utility in the eyes of the public was considered an act of piety, and therefore a matter of achievement. Hirai's place, therefore, as a builder in the history of Candrapur is the same as that of Ahilyabai Holkar in the eighteenth century India.”

She constructed and renovated multiple mandirs across Chandrapur and Gadchiroli. At Vairagad, she constructed the mandir of Goraja.

The governance of the Chandrapur kingdom was later passed to her adopted son, Ram Sah, who ruled from 1691 to 1735. His reign was increasingly challenged by the growing power of the Marathas.

Maratha Incursions into Vidarbha

During the end of the 17th century, the Maratha empire was gaining prominence in the Deccan. The empire was founded by Chhatrapati Shivaji in 1674 CE and expanded into a full fledged empire in the 18th century under the leadership of Peshwa Bajirao (the minister of Shivaji’s grandson Shahu). Overtime, the position of the Peshwa became hereditary and the Maratha State became a confederacy of five chiefs (Peshwas, Bhonsles, Holkars, Gaekwads and Scindias) under the nominal leadership of the Peshwa at Poona (present Pune) in western India. Out of these, the Bhosales established power in East Vidarbha, including Gadchiroli by the 18th century.

Parasoji Bhosale, son of Mudhoji Bhonsle, died in 1709 and was succeeded by his son Kanhoji Bhosale. The nature of Kanhoji’s involvement in Chandrapur remains unclear. Some accounts suggest he launched expeditions, while others cast doubt on their extent. The Gazetteer (1909) advises caution regarding these reports, noting: “the account of Kanhoji's invasion of Chanda too has to be taken with a grain of salt.”

By 1720, however, the Marathas had secured from the Mughal emperor the right to collect Chauth and Sardeshmukhi from Berar, which included parts of present-day Gadchiroli.

After Kanhoji’s death, Raghuji Bhonsle, nephew of Kanhoji, became Sena-Saheb-Subah in 1728. He continued to assert Maratha influence in the east, including the Chandrapur and Gadchiroli regions. While these districts were not annexed outright, they became tributaries of the Maratha administration.

Raghunath Singh’s Rebellion & the Fall of the Chanda Kingdom

In the mid-18th century, while Raghuji I Bhosale was engaged in military campaigns in Bengal, unrest emerged in the Gond kingdom of Deogarh. The Gond kings, who had ruled parts of central India for centuries, governed with the help of high-ranking officials, among whom the most powerful was the Diwan, or chief minister. In this case, the Diwan, Raghunath Singh, a key figure in the Deogarh kingdom’s administration, attempted to assert independence from Maratha influence.

Raghunath Singh allied with Nilkanth Sah, who is regarded as the last King of the Chanda Kingdom, in a bid to overthrow Maratha authority. Sensing the threat, Raghuji I diverted his attention from Bengal and marched on Deogarh in 1748 CE. The rebellion was swiftly crushed, Raghunath Singh was killed, and Nilkanth Sah was defeated.

A treaty followed in 1749 CE, under which Nilkanth Sah was forced to surrender two-thirds of his kingdom’s revenue to the Marathas. Strategically important forts such as Vairagad were ceded to Raghuji’s control. This marked a turning point in local governance as the Gond dynasty, which had maintained authority for centuries, was gradually replaced by a Maratha administrative structure.

Under the Rule of the Bhosales of Nagpur

Following the consolidation of Maratha power in the region, Raghuji I Bhonsale ruled until his death in 1755 CE. His passing led to a succession dispute between his sons, Janoji and Mudhoji, which introduced a period of political instability that extended beyond the central court to the outer territories, including Chandrapur and its dependency, Gadchiroli.

In an effort to restore order, the Peshwa in Pune intervened, temporarily resolving the conflict by assigning Janoji to Nagpur and Mudhoji to Chandrapur. However, the settlement proved fragile. Mudhoji continued to pursue control over Nagpur, and his ongoing political maneuvering—with both the Peshwa and rival factions within the Bhosale family—resulted in prolonged administrative uncertainty.

As a consequence, governance in peripheral regions like Chandrapur and Gadchiroli appears to have suffered neglect. Development stagnated, and local administration remained weak during this turbulent period.

After Janoji’s death in 1772 CE, his adopted heir, Raghuji II, assumed power in 1775 CE, with Mudhoji acting as regent. This helped restore a degree of stability to the Nagpur dominion. By 1830 CE, Raghuji III, son of Raghuji II, was formally recognized as the ruler of Nagpur and its territories, which continued to include Chandrapur and the area now known as Gadchiroli.

Rise of the British & the End of Maratha Control

The early 19th century brought another shift in authority. In 1816 CE, Appasaheb Bhonsale of Nagpur entered into a Subsidiary Alliance with the British East India Company. This diplomatic agreement granted the British increased influence over Nagpur and its outlying territories, including Chandrapur and Gadchiroli.

After a failed rebellion against the British, Appasaheb lost direct control. By 1818 CE, the British had established effective control over Chandrapur district. When the British suspected that the fugitive Peshwa might attempt to take refuge in Chandrapur Fort, they marched toward it, encountering and defeating local Gond resistance along the way. This conflict, though focused elsewhere, also disrupted life in Gadchiroli, which lay along strategic routes and shared administrative ties with Chandrapur.

During the period between 1818 and 1830, the region was administered under a British protectorate. Several Gond chiefs in the interior areas, including parts of present-day Gadchiroli, expressed opposition to the new administration. Isolated instances of resistance were reported, particularly in forested zones where local leadership structures remained intact. In response, British officials initiated a process of political consolidation and concurrently, efforts were made to stabilize agricultural production and settlement patterns. Abandoned villages were resettled, irrigation systems were repaired, and land assessments were revised. Gadchiroli was gradually brought under a new administrative framework, with Chandrapur serving as the district headquarters (see more below).

In 1830 CE, upon the coming of age of Raghuji III, the Bhonsales were restored to power in Nagpur and its territories, including Chandrapur and Gadchiroli, under British supervision. When Raghuji III died without an heir in 1853 CE, the British implemented the Doctrine of Lapse, annexing the entire Nagpur Province, including Chandrapur and Gadchiroli, into British India. From this point forward, Gadchiroli became part of the Central Provinces, administered directly by the colonial government.

Colonial Period

Prior to 1854, the boundaries of Chandrapur (then Chanda) district remained ill-defined. In that year, formal delineation of the territory was carried out by the British authorities and Chandrapur was established as a distinct administrative district under British rule.

At the time of its formation, the district comprised three primary tehsils: Mul, Warora, and Brahmapuri. Subsequent territorial reorganization led to the addition of four more tehsils, with administrative headquarters established in Sironcha, located in the southern part of what is now Gadchiroli District.

Further adjustments to the administrative structure occurred in 1905, when a separate Gadchiroli tehsil was created. A tehsil headquarters was established at Gadchiroli town, marking the beginning of its emergence as a local administrative centre. From this period onward, Gadchiroli’s administrative role within the larger Chandrapur District steadily expanded, setting the foundation for its future development as a district in its own right.

The First War of Independence, 1857

Within three years of establishing British administration in Chandrapur (then Chanda District) in 1854, the region experienced the reverberations of the Revolt of 1857, commonly referred to as India’s First War of Independence. In its wake, an organized uprising took shape in the forested and zamindari-held regions of present-day Gadchiroli and Chandrapur districts.

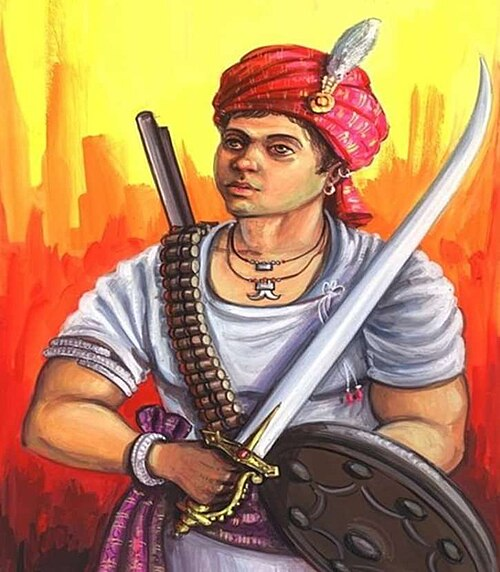

This uprising marked one of the earliest coordinated resistances to colonial rule in the region. It was led by Baburao Sedmake, Zamindar of Molampalli (which comprises parts of what is now Etapalli taluka of Gadchiroli). Belonging to a Gond zamindar family, Sedmake was born in Kishtapur village (Aheri) in 1833, and emerged as a prominent local leader during the rebellion.

In early 1858, he mobilized a force of approximately 500 combatants, comprising individuals from the Gond, Maria, and Rohilla communities. With this force, Sedmake launched a series of armed engagements against British detachments across the region, initiating a phase of active resistance from the interiors of Gadchiroli.

On 13 March 1858, Sedmake’s forces engaged British troops near Nandgaon, in present-day Chandrapur district, and are said to have succeeded in repelling them. He was subsequently joined by other zamindars, including Vyankat Rao of Adpalli and Ghot (now Allapalli and Ghot villages in Gadchiroli). Together, they assembled a combined force of over 1,200 men and gained control over parts of the Rajgad pargana, extending the rebellion to a wider territory.

In the following weeks, confrontations continued. Battles were fought at Saganapur on 19 April and at Bamanpet on 27 April, both located in present-day Chamorshi tehsil. During this phase, rebel forces also attacked a British telegraph camp at Chinchgundi on the Pranhita River, disrupting lines of communication. These coordinated actions, largely centered in Gadchiroli’s forested interior, posed a sustained challenge to British operations in the region.

In response, the British administration, under Deputy Commissioner R.S. Crichton launched multiple expeditions to suppress the uprising. Failing to subdue the rebellion through direct military action, Crichton turned to local intermediaries. He issued a warning to Rani Lakshmibai of Aheri, a regional zamindarini, that her estate would face punitive measures if she failed to assist in Sedmake’s capture.

In July 1858, Lakshmibai’s forces apprehended Sedmake at Bhopalpatnam. Though he briefly escaped with the help of his guards, he was recaptured on 18 September 1858 and brought to Chandrapur for trial.

On 21 October 1858, Sedmake was tried and convicted on multiple charges, including armed rebellion, obstruction of British forces, and looting of government camps. He was sentenced to death and executed the same day in front of Chandrapur Jail. His estate was confiscated under Act XIV of 1857.

Vyankat Rao, Sedmake’s associate, fled to Bastar but was eventually handed over by the Raja of Bastar and sentenced to life imprisonment in 1860. His sentence followed negotiations led by his mother, Nagabai.

For her role in aiding the British, Lakshmibai of Aheri was rewarded with the zamindari of Adpalli and Ghot, comprising 67 villages. Deputy Commissioner Crichton was honored with the title Companion of the Bath.

Early Nationalist Activity and the Formation of the Chandrapur District Association

The spirit of resistance and the desire for local autonomy did not end with the suppression of the 1857–58 uprising. By the early 20th century, Gadchiroli began to experience the ripple effects of the emerging Indian nationalist movement, which was gaining strength across the Central Provinces. In response to this growing political consciousness, British authorities introduced stricter measures in 1913 to curb dissent throughout the region, including Chandrapur district, of which Gadchiroli was then a part.

That same year, the Chandrapur District Association was established as a platform for organised political engagement. Drawing support from across the district, the Association reflected the emergence of a middle-class leadership committed to voicing the concerns of both urban and rural communities, including those in Gadchiroli.

The Association took up a range of issues through legal petitions, appeals, and correspondence. These included:

- Petitions from peasants seeking tax relief during famines or surplus years.

- Requests for re-assessment of crops, particularly when revenue officials were suspected of inflating estimates.

- Complaints from local merchants, which were formally submitted to government authorities for redress.

Though operating within a constitutional and non-violent framework, the Association’s activities laid the foundation for deeper political consciousness in the district. It functioned during a period often referred to as the pre-Gandhian phase of India’s freedom struggle, influenced in part by the ideas of leaders like Lokmanya Tilak.

It is noteworthy that from the late 19th century to the early 20th century, Gadchiroli also saw the emergence of numerous political leaders. These leaders played active roles in the independence movement, engaging with national and regional organizations such as the Congress, the Swarajya Party, and Chandrapur's municipal council. Their contributions marked a significant period of political and social mobilization in the region.

Post-Independence

Following India’s independence in 1947, Gadchiroli remained a part of the larger Chandrapur district in the Central Provinces and Berar, which became part of Madhya Pradesh. With the reorganization of states in 1956, it was included in the Bombay State. After the linguistic division of Bombay in 1960, Chandrapur district, including Gadchiroli, became part of the new state of Maharashtra.

In 1982, Gadchiroli district was created through the separation of the Gadchiroli and Sironcha tehsils from Chandrapur. The formation of the district was driven by administrative considerations and the need for more targeted development in the region.

Still since its formation, Gadchiroli has consistently ranked among Maharashtra’s most underdeveloped districts. Despite its wealth of natural resources, including minerals, forests, and river systems, the district has faced significant barriers to socio-economic progress. A large proportion of the population depends on the primary sector, particularly agriculture, forestry, and subsistence activities, with limited access to higher education, industry, or large-scale employment.

Red Corridor & Naxalite Movement

Gadchiroli district forms part of the area officially designated as the "Red Corridor," a term used by government agencies and security bodies to describe districts in which Naxalite–Maoist activity has been reported at scale.The movement in the district began in the 1980s, expanding from neighbouring areas of Chhattisgarh and Telangana. It drew support from long-standing issues including land alienation, restricted access to forest resources, limited state services, displacement due to infrastructure and mining projects, and the absence of regular administrative outreach in interior areas.

Maoist groups established themselves in remote and forested parts of the district, where state institutions and infrastructure were often limited or absent. In response, the government deployed security forces and launched coordinated counter-insurgency operations. Gadchiroli is currently among the most securitised districts in Maharashtra.

The prolonged conflict has significantly impacted local communities. Civilians have been affected by the activities of both armed insurgent groups and state security forces. Reports of violence, arrests, restricted mobility, and surveillance have emerged from various parts of the district. Prateek Goyal (2019) in his article illuminates on how individuals involved in land rights movements and forest governance initiatives have, in some cases, been detained under anti-insurgency laws. The ongoing conflict continues to shape patterns of livelihood, mobility, and governance across the district.

Social Developments & Community-Based Programs

SEARCH (Society for Education, Action, and Research in Community Health)

Gadchiroli has also been the site of several community-driven initiatives aimed at improving public health, promoting local governance, and fostering sustainable development. Among the most notable of these is SEARCH (Society for Education, Action, and Research in Community Health), which is widely recognized as a model for grassroots public health innovation.

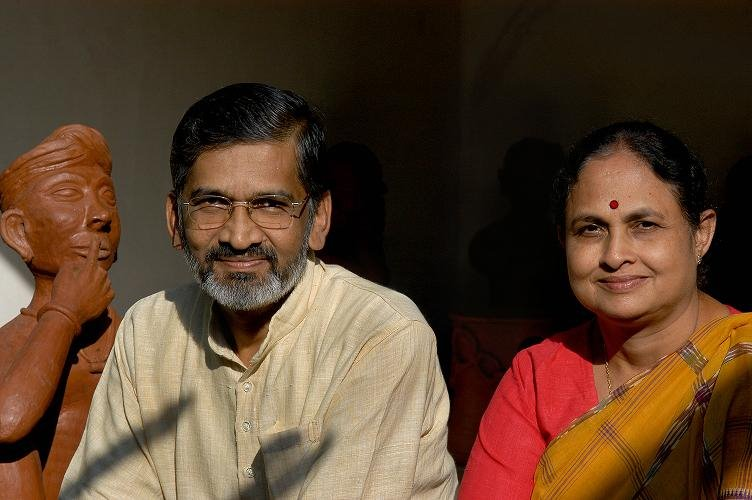

Founded in 1986 by Dr. Abhay Bang and Dr. Rani Bang, SEARCH was established with the goal of addressing the healthcare needs of marginalized rural and tribal communities in the district. Over the years, the organization has played a significant role in transforming healthcare delivery in the region and has influenced public health approaches across Maharashtra.

One of SEARCH’s flagship efforts is the Gadchiroli Project, which emphasizes community-based healthcare delivery. The organization has set up health and wellness centers that provide essential services such as maternal and child health care, basic medical treatment, and preventive health education. A core aspect of the initiative is the training and empowerment of local community health workers, equipping them to address health issues directly within their communities.

SEARCH is also involved in field-based research, examining health trends and socio-economic conditions affecting the region. Its findings are used to design programs tailored to local needs. SEARCH also manages Maa Danteshwari Dawakhana, a rural hospital facility in the district.

Mendha Lekha & the Forest Rights Act

In addition to health and welfare initiatives, community-led efforts have also influenced land and forest governance within the district. One such development occurred in the village of Mendha Lekha, situated in Dhanora taluka, which in 2009 became the first village in the country to receive Community Forest Rights (CFR) under the provisions of the Forest Rights Act (2006).

Under this arrangement, the gram sabha of Mendha Lekha was granted collective rights over approximately 1,800 hectares of forest land. The village assumed responsibility for the management and regulated sale of bamboo and other non-timber forest produce. A locally administered tendering system was introduced, and revenue generated—reported to exceed ₹1 crore in a single season—was allocated to development works, including road maintenance, soil conservation, the construction of wildlife waterholes, and training programmes for local youth.

The village follows a governance model based on swayamshasan (self-rule), with decisions undertaken through open assemblies and consensus-based deliberation. It is also registered for taxation and holds a Permanent Account Number (PAN), thereby operating within both traditional and statutory administrative frameworks.

While the recognition of Mendha Lekha’s rights in 2009 received national attention, the broader implementation of the Forest Rights Act across the district has remained inconsistent over time. As of 2012, over 700 Community Forest Rights (CFR) claims had been recorded in Gadchiroli since the Act came into force in 2006. However, as noted by Subramaniam (2012), only a limited number of villages had, by that point, secured functional control over forest resources. Subsequent observations suggest that progress has continued to be slow. Factors cited include procedural complexity, administrative reluctance, and inadequate dissemination of information among eligible forest-dependent communities.

Sources

Amit Bhagat. 2019. Baburao Sedmake: Adivasi Hero of 1857. Peepul Tree.https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindi…

Amit Sopan Bhagat. 2019. Recent Discovery of Megalithic Sites in Chandrapur, District of Maharashtra. Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology. Vol. 7.

Ankush Dahat. 2019. Discovery Of New Megalithic Burials In Gadchiroli District (Vidarbha), Maharashtra. Department of Ancient Indian History Culture and Archaeology, Rashtrasant Tukdoji Maharaj Nagpur University, Nagpur.

Anusha Subramanian. 2012. Mendha Lekha is the first village to be granted community forest rights. Business Today.https://www.businesstoday.in/magazine/featur…

Dr. V.V. Mishra, P. Setu Madhava Rao, G. A. Sharma, et al. 1972. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Chandrapur District. Mumbai.

Ganesh V. Halkare. 2005–06. Extinct and Living Megalithism in Vidarbha. Vol. 66. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress.https://www.jstor.org/stable/44145958

Kartik Lokhande. 2023. Vairagad Fort: A Story of Neglect. The Hitavada.https://www.thehitavada.com/Encyc/2023/10/3/…

Lakshmi Subramanian. 2021. Markandeshwar Temple, Gadchiroli.https://sahasa.in/2021/01/22/markandeshwar-t…

M. C. Joshi ed.1993.Indian Archaeology 1988–89: A Review. Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi.https://nmma.nic.in/nmma/NAS1/nmma_doc/IAR/I…

Ministry of Road Transport & Highways. 2020. PIB Mumbai.https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.as…

N.P. Chakravarti. 1963. Epigraphia Indica. Archaeological Survey of India. Vol. 25.

Neetu Gode. 2021.Rural Development Programmes: A Case of Gadchiroli, Maharashtra.International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology. Vol. 8. Issue 4.

Prateek Goyal. 2019. ‘A life without fear of security forces and Naxalites, can any party promise us that?’ The News Laundry.https://www.newslaundry.com/2019/04/09/gadch…

Russel V. ed. 1905. Central Provinces District Gazetteers: Chanda District. Pioneer Press, Allahabad.

Shashishekhar Gopal Deogaonkar. 2007. The Gonds of Vidarbha. Concept Publishing Company.

The News Dirt. History of Gadchiroli: From Ancient Settlements to a Tribal District Facing Conflict and Change.https://www.thenewsdirt.com/post/history-of-…

Vijay Pinjarkar. 2016. Paleolithic tools discovered in Sironcha’s fossil park. Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/nag…

Last updated on 11 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.