Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Kachargadh Caves

- Early Iron Age Agrarian Settlement at Malli

- Early Empires and the Spread of Buddhism

- Trade under Satavahanas

- Political Shifts and Dynastic Transitions

- Medieval Period

- The Gondwana Kingdom

- Gondia under Mughal Relations

- The Rise of the Bhosales

- The Bengal Campaign and Strategic Use of Bhandara

- Internal Conflict Among the Marathas

- British Influence and Subsidiary Alliance

- Kamtha Revolt and British Suppression

- Colonial Period

- Famine & Railways in Gondia

- Satyagraha and the Freedom Movement in Gondia

- Post-Independence

- Tibetan Settlement in Gondia

- Sources

GONDIA

History

Last updated on 11 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Gondia district lies in the Wainganga region of eastern Maharashtra, close to the borders of Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. Archaeological findings point to continuous human settlement for thousands of years, placing it firmly within the early historical landscape of central India. In ancient times, the area fell under the Maurya and Satavahana empires, whose reach extended across much of the Deccan and central Indian plains.

By the medieval period, Gondia became part of the Nagpur Kingdom, ruled first by the Gond dynasty. It later came under the control of Bakht Buland Shah and was eventually absorbed into the Maratha state under the Bhosale rulers of Nagpur. These shifts, in many ways, reflected broader changes in regional power across eastern Maharashtra. During the colonial period, Gondia remained under British administration as part of Bhandara district, a structure that continued after independence. In 1999, the region was formally established as a separate district, marking the latest chapter in its evolving political identity.

Etymology

The origin of the district’s name is particularly interesting, as it is rooted in the Gond community, who have for long inhabited the region. According to local accounts, the community was associated with the collection of lak (sealing wax) from the Palas tree and gum from the Babul tree. In Hindi, this gum is known as gond, which is believed to have influenced the naming of the area.

Ancient Period

Gondia district has been inhabited since ancient times. Although written records from these early periods are scarce, archaeological remains and several ancient sites across the area provide important insights into its prehistoric past and early cultural development.

Kachargadh Caves

One of the earliest indicators of human presence in the region comes from the Kachargadh Caves, located in Darekasa village. Archaeological evidence traces habitation here to the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic periods (c. 5,00,000 BCE to 10,000 BCE). This era, classified as the Early Stone Age, was marked by cave-dwelling communities who used basic stone and bone tools, including crude axes, to hunt birds and wild animals.

Excavations at the site have revealed stratified remains from both Palaeolithic phases, leading many to regard it as one of the largest natural cave complexes in Asia with Stone Age remains.

In addition to its archaeological importance, the site holds enduring cultural value for the Gond community, who believe the caves are home to the shrine of Devi Kali Kankali. Today, the site continues to attract many yatris annually from various Indian states.

Early Iron Age Agrarian Settlement at Malli

Another significant site in the district is Malli, located in Tirora taluka, which provides insight into the Early Iron Age period (c. 1500 BCE to 200 BCE). Excavations conducted by the Department of Archaeology, Maharashtra, have unveiled Malli to be a “single culture site” (an area that is not bounded by political borders but practices a single culture).

Among the most notable findings at the site is the presence of nearly 400 megalithic burials, suggesting that Malli functioned both as a settlement and a burial ground. The number and organisation of these burials point to a stable, socially structured community.

In addition to burial practices, archaeobotanical analysis from Malli reveals important aspects of the local economy. Grains such as rice, millets, and pulses were cultivated and consumed, with rice appearing as the dominant crop. This provides insight into both seasonal agricultural cycles and dietary patterns of the time.

Incidentally, the prominence of rice cultivation observed in the Early Iron Age has continued into the present. Gondia today remains a major rice-producing region.

Early Empires and the Spread of Buddhism

Gondia gradually became part of larger political formations. While written records from the earliest phases remain limited, archaeological evidence from across Vidarbha, including Gondia, reflects a steady shift from isolated settlements to organised rule under successive dynasties. Over time, this area was drawn into wider patterns of administration, trade, and cultural exchange that connected it to neighbouring regions in India.

The earliest known political influence in the broader region traces back to the Mauryan Empire under Emperor Ashoka. While little is known about Gondia during this period, archaeological findings from nearby Bhandara suggest that the area may have been within the Mauryan sphere of influence. Buddhist stupas and railing pillars found at sites like Pauni suggest active religious and cultural exchange, likely supported by trade routes connecting northern and southern India. Given Ashoka’s role in promoting Buddhism, it is also possible that the religion began to spread through this region during his reign.

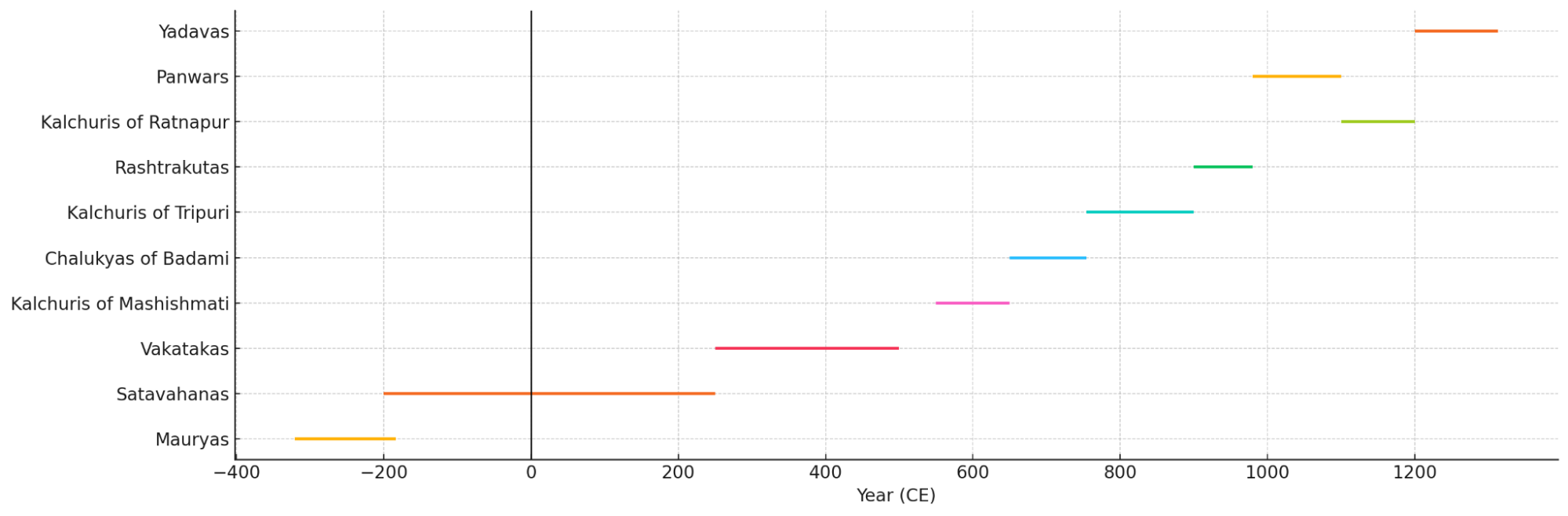

After the fall of the Mauryan Empire, it is said that the region briefly came under the Shunga dynasty. By around 200 BCE, Vidarbha came under the control of the Satavahanas, who ruled for nearly 400 years. This era saw significant economic and commercial growth, supported by the introduction of a standardized coinage system and the expansion of internal trade. Archaeological and historical evidence points to increased commercial activity in Vidarbha under Satavahana rule.

Trade under Satavahanas

Considering the interconnectedness of regions during this time, it is plausible to infer that the economic expansion observed in Vidarbha would have had a similar impact in Gondia. At Pauni, in present-day Bhandara district, excavations have uncovered Satavahana-era coins and urban remains, indicating that it was a significant settlement, possibly with administrative and trade-related functions.

Political Shifts and Dynastic Transitions

After the decline of the Satavahanas, the influence of the Western Kshatrapas extended into parts of the broader region. A memorial pillar attributed to Mahakshatrapa Rupiamma, found near Pauni, suggests their presence in Vidarbha during the 2nd to 3rd centuries CE, though the extent of their control over Gondia remains unknown.

In the latter half of the 3rd century CE, the Vakatakas rose to power in Vidarbha and ruled for over 250 years. During the reign of Narendrasena, the sixth Vakataka ruler, it is said that his capital was relocated from Nandivardhan (present-day Nagardhan in Nagpur) to Padampur, near present-day Amgaon in Gondia district, due to foreign invasions in East Vidarbha. This move underscores the political relevance of the Gondia region during this period.

Further traces of the dynasty’s presence is the discovery of a 1,500-year-old brick Shiva Mandir in Shenda village of the district, attributed to the Vakataka era, reflecting both religious and architectural developments of the time.

Following the decline of the Vakatakas, the Kalachuris of Mahishmati, ruling from present-day Maheshwar in Madhya Pradesh, gained control over parts of Vidarbha. Their territory extended into western Maharashtra, including areas once held by the Vakatakas.

Around the mid-6th century, the Kalachuris of Mahishmati, based in present-day Madhya Pradesh, expanded into Vidarbha. In the early 7th century, the Chalukyas of Badami advanced into the region from the south. Their rule lasted until the mid-8th century, but their hold in eastern Vidarbha, including areas like Gondia and Bhandara, appears to have been limited. Here, they were displaced by the Kalachuris of Tripuri, who, according to the Bhandara district Gazetteer (1908), likely controlled this territory during the period.

By the 10th century, the Rashtrakutas had emerged as a dominant power in the Deccan and expanded into eastern Vidarbha. The Gazetteer also notes that the Panwars may have ruled the area briefly toward the end of the century. In the 12th century, the region once again came under the territory of the Kalachuris of Ratnapura.

By the mid-13th century, the Yadava dynasty had extended its control over parts of the Vidarbha region. Their rule is associated with the development of Hemadpanthi architecture, a distinctive style named after Hemadpant, a minister in the Yadava court. The Yadavas remained in control until they were defeated during Alauddin Khilji’s Deccan campaign in the late 13th century.

Medieval Period

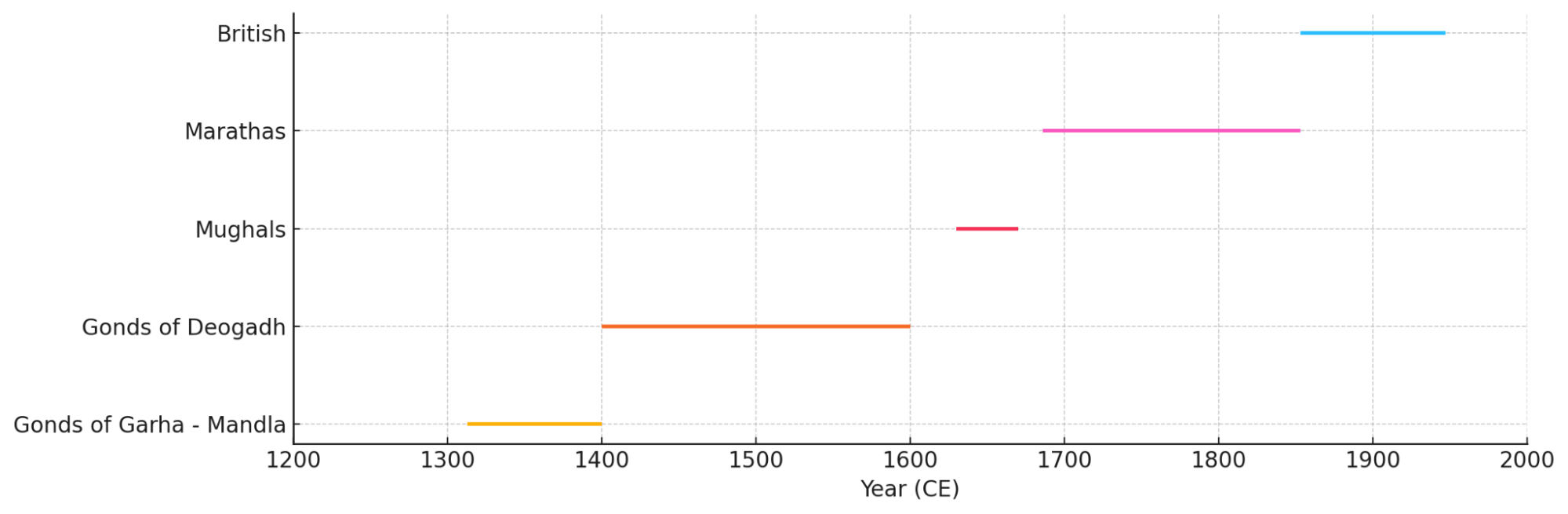

The political history of Gondia district enters a new phase in the medieval period, beginning with the annexation of Central India by Alauddin Khilji in the early 14th century. This initiated a broader pattern of political realignment in the Deccan, leading to the emergence of kingdoms such as Gondwana, which would come to include the area now known as Gondia.

The Gondwana Kingdom

The Gondwana kingdom emerged between the 14th and 15th centuries, with the Garha-Mandla kingdom (present-day Jabalpur–Mandla in Madhya Pradesh) marking its first major centre. Gondia district formed part of this political entity, though detailed records on its administration, economy, and society remain scarce.

In the 15th century, King Jatba founded the kingdom of Deogarh (present-day Chhindwara), carved from Garha-Mandla. His domain included large parts of central India, such as Nagpur, Betul, Bhandara, and parts of Seoni and Balaghat, encompassing Gondia. The Bhandara Gazetteer (1908) identifies Jatba as the first historically documented leader of the mountain Gonds, though little is known about his early rise to power.

Gondia under Mughal Relations

During Akbar’s expansion into the Deccan, the Mughals did not fully annex the Kingdom of Deogarh. Instead, it remained semi-autonomous under the Gond ruler Jatba, who paid regular tribute to the Mughal Empire. This arrangement is documented in the Ain-i-Akbari by Abul Fazl, which states that Deogarh paid an annual tribute and maintained a military force of “2,000 horses, 50,000 foot soldiers, and 100 elephants.” These details highlight the strength and regional influence of Jatba’s rule, which likely included areas now part of Gondia.

After Akbar’s death, however, the stability of the Deogarh kingdom declined. According to the Bhandara district Gazetteer (1908),“between 1637 and 1670, the kingdom faced multiple invasions by the Mughals, primarily due to its inability to meet the obligations of the annual tribute.” The cumulative impact of these invasions, compounded by the ongoing burden of tribute payments, weakened the kingdom’s economy and exhausted its resources. Since Gondia was part of the Deogarh domain, it can be reasonably inferred that it experienced a similar fate during this period of adversity.

Furthermore, it is noted in the Bhandara district Gazetteer (1908) that “the centre and east of the district were covered by dense forest and tenanted only by wild animals and forest tribes.” This suggests that Gondia had limited political or economic importance at the time, with much of the area remaining forested and sparsely inhabited.

Deogarh’s later history had little direct relevance to Gondia until a significant turning point occurred with the incorporation of Bhandara, including present-day Gondia, into the Nagpur Bhosale kingdom as part of Prant Wainganga.

The Rise of the Bhosales

Bakht Buland, a Gond king who initially ruled from Deogarh (near present-day Chhindwara in Madhya Pradesh), later shifted his capital to Nagpur, which he began developing into a major political center. He was succeeded by his son, Chand Sultan. After Chand Sultan’s death around 1738, the Gond kingdom was thrown into political turmoil, with rival claims to the throne. To secure power for her son, Chand Sultan’s widow, Rani Ratan Kuvar, appealed to Raghuji Bhosale I, a rising Maratha leader of the Bhosale dynasty (see Nagpur for more).

Raghuji agreed to intervene and launched a military campaign eastward. He successfully captured the fort of Pauni in present-day Bhandara district and eventually took control of Deogarh, ending Gond rule in the region. Although historical records offer limited details on the specific impact of these events on Gondia, it is likely that by the mid-18th century, following the Maratha conquest of Nagpur and its neighboring areas, regions such as Bhandara and Gondia came under Bhosale administration. The Marathas integrated Gondia into their administration, making it a part of the Nagpur Subha (province).

The Bengal Campaign and Strategic Use of Bhandara

Raghuji Bhosale and Peshwa Bajirao I both aimed to expand Maratha influence eastward. Over the course of nearly a decade, both leaders launched military campaigns into the eastern territories. This effort culminated in 1751, when Raghuji Bhosale successfully annexed Cuttack (in present-day Odisha) and secured the right to collect chauth from Bengal and Bihar.

Its location, flanked by dense forests to the north and south, provided a relatively secure passage for the movement of troops and supplies. Although historical records do not detail Gondia’s exact role in these campaigns, it is reasonable to assume that, as part of Bhandara district at the time, it was likely part of the broader logistical network supporting these movements.

Internal Conflict Among the Marathas

After the death of Raghuji Bhosale I in 1755, the Bhosale kingdom experienced a period of internal instability due to disputes over succession. His eldest son, Janoji Bhosale, eventually succeeded him and assumed the title of Sena-Sahib-Subha. However, Janoji’s tenure was marked by continued tensions with the Peshwas and shifting alliances with regional powers. According to the Bhandara District Gazetteer (1908), Janoji was known for changing loyalties, at times aligning with and later opposing both the Peshwa and the Nizam of Hyderabad. This political uncertainty affected administrative regions under Bhosale control, including Bhandara and present-day Gondia, which were integrated into the Nagpur kingdom.

Following Janoji’s death, another succession conflict emerged. His adopted son, Raghuji II, was still a minor, leading to a power struggle between Janoji’s brothers, Madhoji and Sabaji. The conflict concluded with Madhoji gaining control of the kingdom. After Madhoji's death in 1788, Raghuji Bhosale II assumed the throne and governed during a period of prosperity and administrative expansion.

However, this period of prosperity was short-lived. By the early 19th century, the East India Company had begun to assert increasing control across the Deccan. Their growing influence marked a significant shift in the political landscape of the region, steadily eroding the authority of regional powers such as the Bhosales. For Gondia, this era signaled the beginning of a new chapter shaped not by local rulers, but by the expanding reach of British colonial power.

British Influence and Subsidiary Alliance

The early 19th century brought increasing pressure from the East India Company. After Raghuji II’s death in 1816, internal power struggles weakened the Bhosale kingdom. The new ruler, Appasaheb, entered into a Subsidiary Alliance with the British in 1818.

Kamtha Revolt and British Suppression

In 1818, during the final phase of the Third Anglo-Maratha War, disturbances broke out in the region as a result of Appasaheb Bhosale’s revolt against the British. One of the key centres of this uprising was Kamtha village (in present-day Gondia district), where the local zamindar, Chimna Patel, offered crucial support to the Maratha cause.

The Kamtha Fort became a focal point of resistance, from which the Marathas attempted to extend their influence into surrounding areas. The conflict also spread to nearby regions, including Lanji (now in Madhya Pradesh), located about 50 km from Gondia.

The Bhandara District Gazetteer (1908) quotes Colonel Valentine Blacker from his Memoir of the Maratha War of 1817–1819, offering a first-hand British account of the events. He writes that the hostilities began with “an attack on the Kamavishdar of Lanji (a local revenue officer) and a party of sebandis (armed retainers or sepoys),” during which Chimna Patel’s forces captured the official and dispersed his escort. In response, the British dispatched a detachment under Captain Walliam Gordon, composed of auxiliary cavalry, men from the Nagpur Brigade, and the 6th Cavalry.

Blacker reported that “the enemy were in possession of the fort of Kamtha, from whence they overran all the neighbouring country.” As Gordon advanced toward Nowargaon (modern-day Navargaon, in Chandrapur district), he encountered about 400 men, described as “Musalmans, Gosains, and Marathas,” positioned behind a deep ravine near the village of Nowargaon (present-day Navargaon in Chandrapur district). The confrontation resulted in relatively minor British casualties, while the opposing side were reported to have lost around 150 men.

Following these engagements, the forts of Lanji and Hatta were surrendered. Chimna Patel was captured, confined to Kamtha Fort, and later held on parole in his villages of Navargaon and Zilmili.

After the conflict ended, the British assumed administrative control over the district, which continued until 1830, when Raghuji Bhosale III was restored to power upon reaching maturity. After his death in 1853, the territory was annexed under the Doctrine of Lapse, marking the formal end of Maratha sovereignty in the region.

Colonial Period

The formal beginning of British colonial administration in the Gondia region can be traced to the aftermath of the 1857 uprising, often referred to as the First War of Independence. The widespread unrest across northern and central India compelled the British to rethink their administrative structure. In particular, the British sought greater control over regions that had shown instability or strategic importance.

As part of this response, the British government restructured several provinces and princely territories, leading to the formation of the Central Provinces in 1861. This new administrative unit combined the Saugor and Nerbudda Territories (from present-day Madhya Pradesh) with the recently annexed Nagpur Kingdom, which had come under British rule in 1853 through the Doctrine of Lapse.

The newly defined Nagpur Territory within the Central Provinces included the districts of Nagpur, Chanda, Bhandara, Chhindwara, Raipur, and Sironcha (now part of Gadchiroli), along with the dependent regions of Bastar and Kuronda (present-day Karaunda in Chhattisgarh). Since Gondia was part of Bhandara district, it became a part of this reorganized structure, marking the start of its integration into the colonial bureaucracy and governance system that would shape the region for the next several decades.

Famine & Railways in Gondia

The latter half of the 19th century was marked by recurring famines in the Central Provinces. In response, the British government implemented recommendations of the Famine Commission, leading to the construction of the Nagpur–Chhattisgarh State Railway (NCR) starting in 1878. This line, completed by 1887, passed through Darekasa in Gondia district en route to Dongargarh in present-day Chhattisgarh.

The Gondia Railway Station was inaugurated in December 1888, connecting the region to key trade and administrative centers. This railway infrastructure significantly enhanced economic activity in Gondia, strengthening existing trade routes and encouraging further commerce and settlement. In 1887, the Bengal Nagpur Railway (BNR) was formed to manage and expand the railway network. By 1902, a new line connected Gondia (Maharashtra) to Jabalpur (Madhya Pradesh), with additional branches extending to Mandla (Madhya Pradesh), Seoni (Madhya Pradesh), and Chhindwara (Madhya Pradesh). These developments contributed to the region’s economic growth and its integration into broader colonial trade and transport networks.

Satyagraha and the Freedom Movement in Gondia

In the 1940s, Gondia district saw its own share of participation in the national struggle for independence. As noted in the Bhandara district Gazetteer (1979), the district was actively involved in the broader wave of non-violent resistance against British rule. During the Salt Satyagraha, Gondia witnessed a week of intense activity that included public gatherings, speeches, and workshops. These events led to the arrest of several Congress leaders and marked a period of visible civil disobedience in the region. For a time, local merchants also boycotted the sale of foreign cloth in protest against colonial policies, aligning the district with the wider Gandhian call for swadeshi and non-cooperation.

Beyond these moments of collective protest, Gondia was also home to several individuals who contributed to the freedom struggle and efforts at social reform. Among them were Ganpatlal Pandey, Jawaharlal Sharma, Durgadas Rahangdale, and Hiraman Tikde. These individuals were not only involved in anti-British resistance but also played roles in social reform, focusing on uplifting marginalized communities.

Post-Independence

After India’s independence in 1947, Gondia continued as part of Bhandara district in the Central Provinces. The States Reorganization Act of 1956 resulted in the transfer of Vidarbha, including Bhandara, to the Bombay State. In 1960, with the formation of Maharashtra, Bhandara officially became part of the new state. Later, in 1999, Gondia was carved out as a separate district, marking a new chapter in its administrative history.

Since independence, agriculture has remained a central component of Gondia district’s economy, undergoing significant changes over the decades. The expansion of agro-based industries, particularly rice mills, has contributed to the district’s economic activity and supported local employment.

In addition to economic developments, Gondia district has seen the introduction of various government schemes and legislative measures targeting Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and marginalized groups. These have included financial assistance programs for families affected by caste- or tribe-based violence. The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006) has also been implemented in the district, providing a legal framework for recognizing land and forest use claims by the indigenous communities. Such policies form part of broader state and national efforts to address social disparities alongside economic planning.

Tibetan Settlement in Gondia

One of the more distinctive developments in Gondia’s post-independence history was the establishment of the Norgyeling Tibetan Settlement at Gothangaon in 1972. It was created to accommodate Tibetan refugees fleeing following the Chinese occupation of Tibet, and remains the only Tibetan settlement in Maharashtra.

Located near the Itiadoh Dam, the camp was initially planned to support around 3,000 people. Early residents lived in tents, with permanent housing and basic services gradually developed over time. Over the years, a distinct community took shape, marked by traces of Tibetan culture and daily life. The settlement includes a monastery (Sera Jey Thekchenling), a primary school (Sambhota Tibetan School), and agricultural land provided by the state.

Much of the settlement’s infrastructure was built with international aid. To this day, it operates under the Central Tibetan Administration, and its residents remain stateless, without Indian citizenship. Now over fifty years old, the settlement reflects a lesser-known aspect of Gondia’s post-independence history, connected to India’s broader role in the Tibetan refugee crisis.

Notably, some locals have pointed out that the camp’s location may be linked to the district’s ancient Buddhist past. If so, the choice of site may hint at Gondia’s earlier regional significance and connect the district’s present to an earlier chapter in its history.

Sources

Kartik Lokhande. 2022. Gothangaon Camp: 50 years of grit, challenges, and hope. The Hitavada.https://www.thehitavada.com/Encyc/2022/3/14/…

Maharashtra State Gazetteers. 1979. Bhandara district. Directorate of Government Printing, Stationary & Publications, Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai.

Mayuri Pralhad Patankar. 2018. Kachargarh Pilgrimage of the Gond Adivasis. Sahapedia.https://www.sahapedia.org/kachargarh-pilgrim…

N S Kasturi Rangan and Saibal Bose. The Roaring Journey: Nagput Chuttesgurh Railway to South East Central Railway. South East Central Railway.https://secr.indianrailways.gov.in/uploads/f…

Poulami Ray. 2023. Visualising Region in History: Analytical Study of Evolution of Vidarbha as a Region. Athena. Vol 7.

R.V Russel. 1908. Central Provinces District Gazetteer: Bhandara District, Vol A, Descriptive. Pioneer Press.

Rusty Kiolbassa. 2015. “Contribution of Railroads in Colonial India and Mexico,” Edges of Empire: Ways of Knowing, Southern Methodist University.https://people.smu.edu/knw2399/2015/03/26/co…

Satish Naik, Virag Sontakke. 2022. Plant economy from Early Iron Age site of Malli, Gondia district, Maharashtra, India. Current Science. Vol. 123. No. 7.

Shantaram Bhalchandra, Deo and Jagat Pati Joshi. 1972. Pauni Excavation, 1969–70. Nagpur University, Nagpur.

Virag Sontakke. 2020. Malli: An Early lron Age Site, Gondia District, Vidarbha Region, Maharashtra. Man and Environment. Indian Society for Prehistoric and Quaternary Studies.

Websites Referred: District Court, Gondia, Gondia District: Official Website, Shri Ramakrishna Satsang Mandal, Gondia, Wikipedia.

Last updated on 11 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.