KOLHAPUR

Architecture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Architecture of Prominent Sites

Kolhapur’s architectural landscape is a reflection of its rich cultural and historical heritage, where Maratha, Islamic, and colonial influences converge. From the sturdy military structures of Panhala Fort to the intricate designs of Bhavani Mandir, the city’s architecture reveals the region’s strategic importance and religious diversity. The fortifications and temples, such as the Mahalaxmi Mandir, showcase a blend of indigenous Maratha styles with Islamic decorative elements, while the New Palace illustrates how European styles like Gothic Revival, Renaissance, and Italianate architecture were adapted into royal residences during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Colonial-era buildings across Kolhapur often reflect this stylistic fusion, incorporating arched facades, symmetrical planning, and ornate detailing rooted in European design sensibilities. Together, these architectural forms trace Kolhapur’s transformation under shifting political powers and cultural exchanges.

Mahalakshmi Mandir

Mahalakshmi Mandir is a notable example of medieval Indian mandir architecture. Believed to have been constructed around 700 CE during the Chalukyan era, it is representative of the Hemadpanthi architectural style, characterized by mortarless construction with precisely cut stone blocks. This technique, which involves the meticulous fitting of large stones without the use of mortar, allows the structure to endure the passage of time. The Mandir is predominantly built from black basalt stone, sourced locally, enhancing its connection to the surrounding landscape and reinforcing its durability.

![The Mahalakshmi Mandir is an example of Hemadpanthi architecture, constructed from black basalt without the use of mortar, showcasing the precision and durability of medieval Indian stone craftsmanship.[1]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/architecture/the-mahalakshmi-mandir-is-an-example-of_70UsYDY.png)

The Mandir’s exterior is adorned with intricate carvings and sculptures, showcasing the craftsmanship of the era. The Devi Mahalakshmi stands as a focal point within the Mandir, and the surroundings are embellished with various ornamental details, including precious stones and diamonds. The Mandir features five Shikharas, which are triangular or conical in shape, painted in pale lemon yellow with saffron outlines. The tallest of these is positioned above the garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum). The Shikharas, which appear to be a later addition to the original structure, are a significant architectural element, giving the Mandir its distinctive silhouette against the sky.

![The exterior of the Mahalakshmi Mandir features detailed carvings and sculptures. Notably, the sculpture of Bhagwan Krishna is painted in vibrant colors.[2]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/architecture/the-exterior-of-the-mahalakshmi-mandir-_bd5oxgp.png)

The layout of the Mandir is well-planned, with strong masonry walls surrounding the complex. Inside, the Mandir is divided into several sections, each serving a different function, including the main garbhagriha, antaral, and multiple mandaps dedicated to various Devis and Devtas. The Kirnotsav festival, a festival of sun rays, is celebrated in the Mandir during which sunlight directly falls on the Devi Mahalakshmi, which exhibits careful architectural considerations.

Kopeshwar Mandir

The Kopeshwar Mandir, located on the banks of the Krishna River in Khidrapur, is a significant example of early medieval temple architecture in the Deccan region in the Bhumija architectural style. Though construction began in the 7th century CE, it is said that frequent conflicts between regional powers delayed its completion. It was eventually finished in the 12th century by the Shilahara ruler Gandaraditya and later supported by the Yadava kings. The Mandir is dedicated to Bhagwan Shiv, who is worshipped here in the form of Kopeshwar.

Notably, the Kopeshwar Mandir is celebrated as one of the finest examples of Bhumija-style architecture. Bhumija (meaning earth-born) architectural style, which originated in the Malwa region, is a branch of the Nagara tradition and is characterized by the Mandir’s shikhara rising directly from the ground without a distinct base structure. Another hallmark of Bhumija design is the star-shaped or stellate plan, created by rotating a square on its axis and pausing it at regular intervals. The Kopeshwar Mandir follows this structure and includes all the primary components typical of the style: Garbhagriha (sanctum), Antaral-Kaksha (vestibule), Sabhamandap (assembly hall), and Swargamandap (hall of heavens). The Mandir also reflects influences from other regional styles of its time, including those of the Yadava, Hoysala, Solanki, Chalukya, and Kadamba traditions.

![The Kopeshwar Mandir in Khidrapur, built in the Bhumija style, is constructed entirely from black basalt stone and features finely cut masonry and sculptural bands.[3]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/architecture/the-kopeshwar-mandir-in-khidrapur-built_p3IUAx4.png)

The Swargamandap is one of the Mandir’s most distinctive elements. This circular hall functions as the ceremonial entrance, although access is also possible through the Sabhamandap. It is supported by 48 elaborately carved stone pillars arranged in three concentric circles. Each of these pillars transitions in form from top to bottom, shifting through circular, square, hexagonal, and octagonal profiles. At the centre of the ceiling is a circular opening known as the Brahmarandhra, symbolising the cosmic axis or gateway to the heavens. This oculus may also have served a functional purpose, allowing smoke from yajnas to escape. The layout and detailing of the Swargamandap demonstrate the advanced planning and spatial clarity of Bhumija architecture.

The Sabhamandap is a square hall directly connected to the Swargamandap and accessible from the north and south as well. It is supported by 60 intricately carved pillars, each bearing depictions of mythological scenes, floral patterns, and deities. The large, open design of the hall would have allowed for rituals, gatherings, and communal activities. The acoustic quality and symmetrical arrangement of the pillars suggest an understanding of both spiritual and spatial dynamics.

![The Sabhamandap of Kopeshwar Mandir is supported by 60 intricately carved pillars.[4]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/architecture/the-sabhamandap-of-kopeshwar-mandir-is-_UY7mQSf.png)

The Antaral-Kaksha, or vestibule, connects the Sabhamandap to the sanctum. This square-shaped space is enclosed on three sides and creates a visual and spatial transition from the larger halls to the inner sanctum. The Garbhagriha is square in plan but features a conical superstructure, housing the twin Lingas, Kopeshwar and Dopeshwar. The sanctum is cool, dimly lit, and peaceful, with minimal ornamentation on the inside, guiding focus toward the central deities. Though the original shrine was destroyed in the later medieval period, a reconstructed brick version now stands in its place.

The entire Mandir is constructed using black basalt stone, which is believed to have been transported from southern India via the Krishna River. The precision of the stonework and the fact that such heavy material was moved over long distances reflect the high degree of planning, labour organisation, and technological knowledge at the time. Despite subsequent destruction and mutilation during later invasions, much of the Mandir’s original structure and carvings remain intact.

The exterior of the Mandir is richly decorated with sculptural bands. The Adhisthana (plinth) features the Gaja Patta, a frieze of 92 elephants, each uniquely carved and adorned. These elephants symbolically carry the weight of the Mandir and are often accompanied by small figures of Devis or Devtas standing over them. Above the elephant frieze is the Nara Patta, or strip of men, featuring finely carved figures of dancers, musicians, attendants, and even Persian traders, an indication of active trade relations during the period. The faces of these figures display distinct expressions, and their garments and ornaments are rendered with striking detail.

![The Adhisthana of the Kopeshwar Mandir featuring the Gaja Patta, a frieze of 92 carved elephants, symbolizing strength and spirituality.[5]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/architecture/the-adhisthana-of-the-kopeshwar-mandir-_nxDUGBc.png)

The Mandir walls are further decorated with sculpted depictions of a wide range of animals (bulls, lions, monkeys, boars, tigers, horses), birds (peacocks, swans), reptiles (snakes, crocodiles), fruits (grapes, bananas, sugarcane), and floral motifs, particularly the lotus. Inside the Mandir, 108 stone pillars are carved in a variety of geometric forms, including square, hexagonal, circular, and octagonal shapes. The geometric variation in the pillars adds both structural rhythm and visual complexity to the interior.

Despite centuries of damage, the Mandir retains its architectural grandeur. Much of the exterior and pillar carvings remain intact, and efforts are currently underway to preserve the structure.

Panhala Fort

Panhala Fort, an example of medieval military architecture, is located atop the Sahyadri Range, at an elevation of 2772 ft. above sea level. It was built during the 12th and 13th centuries, with several additions made during the reign of the Bijapur Sultanate and later by the Marathas. The fort is known for its extensive fortifications, which include massive walls, strategically positioned bastions, and carefully designed gates. The location offers a panoramic view of the surrounding valleys and plains, providing a strategic advantage for military defense.

Panhala Fort is an excellent representation of military engineering, with features designed to withstand sieges and facilitate defense, including water storage systems, concealed escape routes, and well-planned bastions. The fort’s architecture combines elements of the Bijapuri style with Maratha military needs, reflecting the fort’s long history of use by various rulers.

![Panhala Fort is an example of medieval military architecture, blending Bijapuri style with Maratha military engineering.[6]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/architecture/panhala-fort-is-an-example-of-medieval-_4Rzdak8.png)

Among its key architectural features is the Teen Darwaza, or Konkani Darwaza, a significant gateway located on the western side of the fort. This gateway, constructed from black stone, was the only access point from the west and is known for its imposing structure. The entrance is adorned with intricate carvings, particularly of the Sharabh motif, symbolizing strength. The large, robust arch design is said to be typical of Bijapuri military architecture, allowing for defensive capabilities in addition to the aesthetic. Its craftsmanship ensures that this gateway serves not only as a passage but as a strategic defense point, equipped to resist attempts at forced entry.

![A view of the Teen Darwaza (Konkani Darwaza) from the inner fort side, showcasing its imposing black stone structure and strategic military design.[7]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/architecture/a-view-of-the-teen-darwaza-konkani-darw_NGOe2O9.png)

Nearby, Sajjakoti stands as another notable structure within the fort’s layout. This open pavilion was built by Ibrahim Adil Shah in the early 16th century. Located at a commanding position within the fort, Sajjakoti was used for strategic observation and administrative functions. The pavilion’s design, incorporating open balconies and expansive views, allowed for monitoring the fort's periphery while also serving as a recreational space. The architecture incorporates Bijapuri stylistic elements, with large, open spaces that highlight both the fort's defensive needs and its administrative function. The pavilion is constructed with stone, featuring tall columns and a flat roof that provides shade, enhancing both utility and comfort.

![The exterior of Sajjakoti showcases its balcony section, with arched openings, designed for strategic observation and ventilation.[8]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/architecture/the-exterior-of-sajjakoti-showcases-its_QiAWbMs.png)

Another essential feature of the Fort’s defensive architecture is the Andhar Bavadi, a unique three-story underground well. It was constructed to provide a hidden water source during long sieges, ensuring the fort's self-sufficiency when external supplies were cut off. The well is accessed by a winding staircase, leading deep below the surface to a reservoir. The design incorporates multiple chambers and concealed exits, allowing for effective water storage while maintaining security.

Furthermore, the Ambarkhana, a set of three granaries built within the fort to store provisions, ensures that the fort could withstand prolonged sieges. These granaries, constructed in the Bijapuri style, feature vaulted ceilings and large, domed chambers designed to protect the stored food from spoilage. The granaries, named after Hindu rivers (Ganga, Yamuna, and Saraswati), are built with thick stone walls to maintain a stable internal temperature. The Ganga Kothi, the largest, could store approximately 25,000 khandis of grain. The architectural design focuses on large, open spaces with domed roofs that allow for maximum storage capacity while maintaining structural integrity.

![Constructed in the Bijapuri style, Ambarkhana is built with thick stone walls, featuring large vaulted openings that serve as granaries to store provisions.[9]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/architecture/constructed-in-the-bijapuri-style-ambar_NmFD7O5.png)

Another crucial military feature of the fort is the Rajdindi Bastion, located at the southern tip of the fort. It is designed with high walls and reinforced with thick masonry, making it one of the most defensible points of the fort. The bastion was used both for surveillance and as a defensive structure during battles. The design of the bastion incorporates a variety of military features, including high parapets, narrow openings for firearms, and a vantage point that allows for control over the surrounding region. The concealed exits from the bastion were historically used for strategic retreats or surprise attacks during combat. Its positioning on the edge of the fort ensures that it remains an integral part of Panhala's overall defensive strategy.

Together, these features contribute to Panhala Fort’s architecture, making it a comprehensive example of medieval military design, integrating both defensive elements and practical structures. The fort's walls, gates, bastions, and water storage systems reflect the need for military resilience, while the granaries and water wells speak to the fort's self-sufficiency. The use of local materials such as black stone and the design of structures for both utility and defense make Panhala Fort a remarkable testament to the military engineering of its time.

Bhavani Mandap

Bhavani Mandap is one of the largest heritage structures in Kolhapur. Built between 1785 and 1800, it served as the royal court and residence of the Chhatrapati rulers of Kolhapur. Located near the Mahalakshmi Mandir, it once functioned as a political and ceremonial centre during the Maratha period.

![Bhavani Mandap features thick stone walls, arched openings, and fine carvings that reflect traditional architectural practices of its time.[10]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/architecture/bhavani-mandap-features-thick-stone-wal_7PDEvOM.png)

The original structure consisted of 14 square halls, but in 1813, an attack and fire destroyed half of the complex. Only 7 of the original squares survive today. The building features thick stone walls, arched openings, and fine carvings that reflect the traditional architectural practices of the time.

A Mandir dedicated to Devi Tulja Bhavani, built exclusively for royal family members, stands within the complex. The entrance hall features chandeliers and a life-size statue of Shahu Maharaj. The site also houses historical artifacts, including hunting trophies of deer and panthers. Today, Bhavani Mandap functions as a public heritage space, retaining both sacred and civic significance.

Town Hall Museum

The Town Hall Museum is a notable example of the neo-Gothic architectural style in Kolhapur. It was constructed between 1872 and 1876 under the supervision of British engineer Charles Mant. Originally built as the town hall during the British colonial period, the building was later used as the residence of the diwan (chief minister) of Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj. It was repurposed as a museum and inaugurated in 1945–46.

The structure features pointed arches, tall windows, and a steeply pitched roof typical of neo-Gothic design. The facade is marked by stone masonry and vertical lines that emphasize height, with detailing that reflects colonial-era aesthetics. A bandstand constructed during the same period once accompanied the building.

![The Town Hall Museum displays neo-Gothic architecture with pointed arches, tall windows, and stone masonry that reflect colonial-era design.[11]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/architecture/the-town-hall-museum-displays-neo-gothi_gIrwE65.png)

Maharaj Palace (New Palace)

Maharaj Palace, also known as the New Palace, combines Indo-Saracenic and Renaissance styles with Rajasthani, Gujarati, and Jain architectural influences. The building is primarily made from locally sourced basalt and sandstone. It was designed by British architect Major Charles Mant and constructed over a span of seven years (1877–1884). Commissioned by Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj, the palace served as the royal residence until the integration of princely states post-1947. Located in Kolhapur, the palace now functions as a museum showcasing Maratha history and legacy.

![The New Palace blends Indo-Saracenic and Renaissance styles with regional influences, constructed in basalt and sandstone with detailed architectural features.[12]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/architecture/the-new-palace-blends-indo-saracenic-an_wIncmOZ.png)

The structure is built around a central courtyard and features a prominent clock tower. The architecture reflects an Indo-Saracenic and Renaissance design, marked by mandir-like columns, ornate balconies, and intricately carved multifoil and trefoil arches. Decorative domes and octagonal towers add a vertical emphasis to the otherwise horizontal expanse of the complex.

![The New Palace’s 85-foot-high clock tower features a Char-Bangla style canopy and a domed chhatri, housing one of India’s largest mechanical clocks, crafted in England in 1877.[13]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/architecture/the-new-palaces-85-foot-high-clock-towe_5kjKlhH.png)

![The façade of the New Palace showcases Indo-Saracenic arches, mandir-style columns, and carved stone detailing.[14]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/architecture/the-facade-of-the-new-palace-showcases-_vM3vzRH.png)

The Darbar Hall, occupying a grand double-height space at the palace’s core, is one of its most captivating features. This ceremonial hall is lined with stained glass windows and intricate fresco paintings illustrating episodes from the life of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. Cast iron balconies rest on mandir-inspired brackets, and the central space is framed by carved columns and lobed arches. A raised throne at one end anchors the hall’s function as a royal audience chamber.

Shalini Palace

Shalini Palace follows a blend of Indo-Saracenic and Renaissance architectural styles. It was built between 1931 and 1934 by the royal family of Kolhapur and named after Princess Shalini Raje. Located on the western bank of Rankala Lake, the palace was converted into a hotel in 1987, becoming the first palace hotel in Maharashtra.

Shalini Palace is built primarily from black basalt stone and Italian marble, giving it a striking visual identity. The front facade is framed by massive stone arches that form a wide verandah and a regal porch. These arches, together with a central clock tower and stained-glass windows, contribute to the palace’s monumental presence. The wooden doors and windows are finely carved and inlaid with Belgian glass etched with the crest of the Kolhapur royal family.

![Shalini Palace’s black basalt and Italian marble facade features wide stone arches, a regal porch, and a central clock tower, reflecting Indo-Saracenic and Renaissance styles.[15]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/kolhapur/architecture/shalini-palaces-black-basalt-and-italia_r7ZeTGt.png)

The interior is designed with ornate woodwork, marble flooring, and stained-glass arches, adding layers of refinement. A central dome and smaller corner pavilions mark the roofline, reflecting the influence of Renaissance revival architecture. The palace is set within formal gardens, which enhance its symmetry and provide a landscaped foreground to the main elevation. The combination of local materials, European design sensibilities, and traditional Indian craftsmanship makes Shalini Palace a notable example of royal architecture from early 20th-century Kolhapur.

Residential Architecture

Homes are spaces we occupy daily, yet few reflect on how they are built or the stories embedded within them. While monumental structures capture the grandeur of dynasties and broader societal patterns across eras, domestic spaces, such as one’s house, arguably, preserve the subtler ways in which culture and history have shaped everyday life through generations.

In Kolhapur, the homes of its inhabitants tell a similar story. The homes of its inhabitants reflect not only architectural styles and material choices but also the deeply rooted cultural practices that influence daily living. A closer examination of these homes reveals hidden narratives, offering insights into how domestic spaces become repositories of cultural heritage and historical continuity.

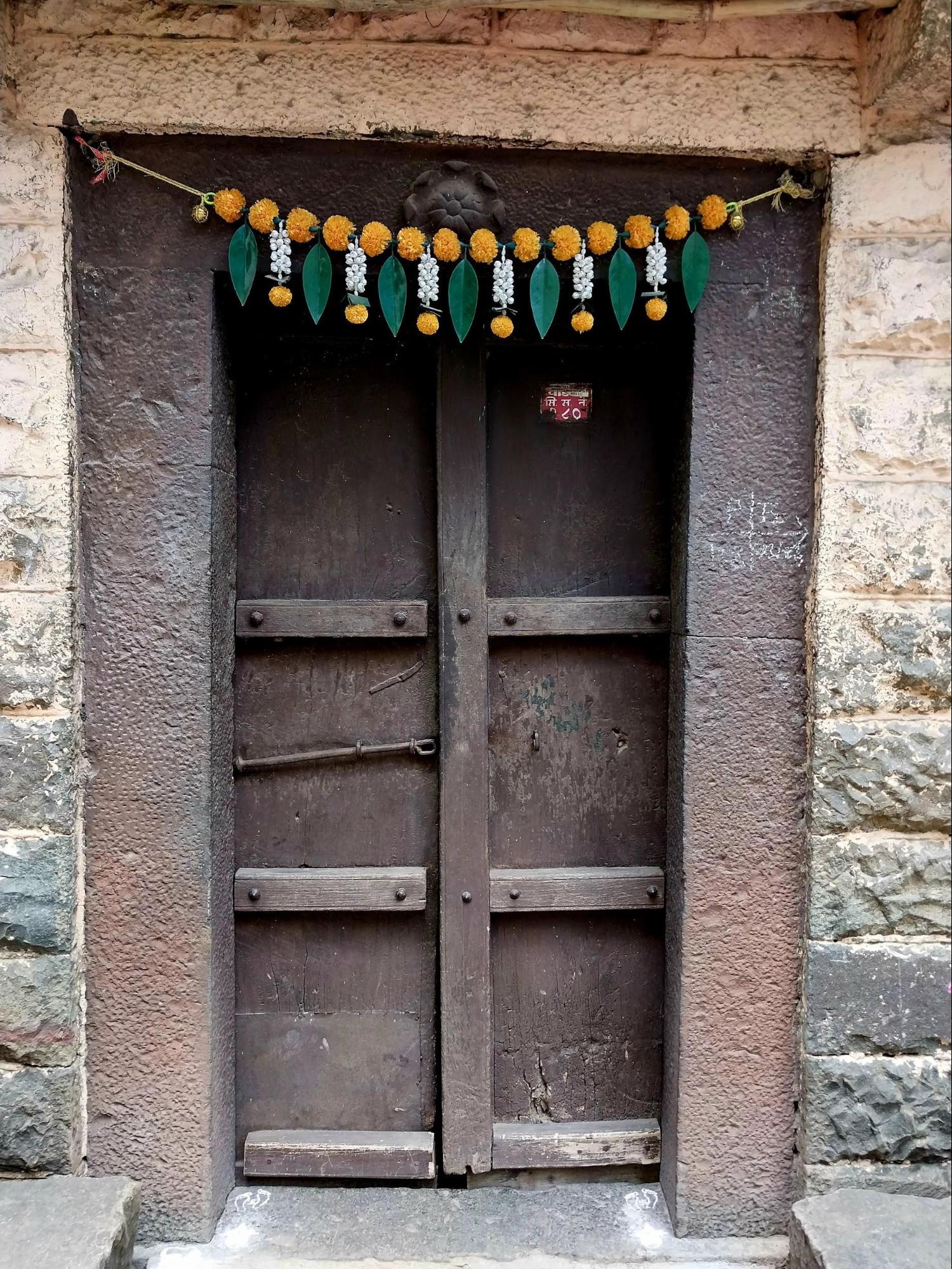

A 19th Century Residence at Sarnaik Galli

Sarnaik Galli is a narrow lane located in the Shivajipeth area of Kolhapur. The galli derives its name from the Sarnaik family, who held a position of significance in the area. The origins of this lane and the family are noteworthy and remarkably tied to the renowned Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj (reign 1894 – 1922) of Kolhapur.

It is said that about 200 years ago, the site where the galli now stands was once a small lake surrounded by Babhali (Acacia) trees, where royal horses would come to drink water. During the reign of Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj, this land was granted to a man named Ramji Raoji Sarnaik, who subsequently served in the accounts department at the Maharaj’s palace. This arrangement provided Ramji Sarnaik with both the land grant and a substantial salary, along with an honorary title bestowed by the Maharaj. Today, within this historic galli lies a three-storey residence which has been home to about five generations of this family.

Estimated to have been built in the late 19th century, the residence spans an area of 2,600 sq ft. The structure retains much of its original character apart from a few renovations that have taken place over the years.

The residence is lined along a galli which has a very intimate layout. Houses are built in proximity to one another, leaving little space between them.

As the streets are narrow, the residences here were originally constructed at a humanistic scale. When it comes to the Sarnaik residence, many features can be seen right at the entrance of the home that were likely made keeping this scale in mind.

The plinth of the house is lower compared to the more modern structures, possibly designed for easy access. The entrance of the door is designed in such a way that it directly opens onto the street. Other than that, the residence shares its walls with the houses adjacent to it, showing how close-knit the layout of the galli is.

The architecture of the house is very striking and interesting. The residential structure was notably built with careful consideration of the local environment and climate. Its composite construction consists of two primary materials, wood and stone. Notably, these two materials are known for keeping the interiors cool even during the peak of summer. The homeowners note how even in the scorching heat outside, for them, there is little to no need for fans or coolers within the house.

The floors of the house are unpaved and traditionally plastered with cow dung, a technique once commonly practiced. However, this traditional flooring technique has not been retained in recent renovations of the house.

Very recently, a room in the backyard was renovated, and cement and tiled flooring have been utilized in the structure; both of which are elements that are much in line with contemporary practices.

The primary material used for doors is wood. The entrance door is positioned exactly at the center of the house and is set within a stone framework.

The entrance also features a floral motif, which likely symbolizes prosperity and serves as a sign of good fortune.

Adjacent to the windows are small devlis that are typically used for lighting diyas during festivals.

The doors at other places have their own distinct designs. However, what they all have in common is that they are double-leaf doors.

The windows are set within a wooden framework, which has traditional railings known as ‘gaj’ attached to them. The site shows symmetric elevation, which means that the entrance door and the windows are elevated in the same line. The upper windows are bigger than the windows on the ground floor, meant for ventilation and proper light.

The balcony features a railing with unique decorative elements that, according to locals, represent a possible design trend of the time, as it can be found across many old structures in the neighborhood.

The residence contains a variety of traditional furniture and tools that reflect the local culture and heritage. These items are characterized by their specific regional nomenclature and practical functions. Though many of these objects are less commonly used today, they remain a significant part of the household’s history and identity.

One such distinctive element is the Saana, a void or space intentionally carved into the tuli (wooden slab) or a wall. While today many regard saanas as spaces that were often used to place lanterns or other household items, locals say that in residences that were over a century old, the Saana served another purpose. Interestingly, it provided a discreet passage for the women of the house when unannounced guests arrived.

Using the staircase, they could pass through the Saana to reach the upper storey, particularly when the visitors were of royal lineage. This feature likely emerged from the social conventions of the era. Today, the Saana within this home has been filled in and is no longer in use.

Many other such elements and objects in the house are peculiar or no longer found in the living spaces of today. Zokala, an iron anchor which was traditionally used to hold swings, is one such object. Khunti was a wooden object attached to walls that served as hangers.

Various traditional storage and utilitarian structures remain intact within the residence. From large handis used for grain storage to mud chulhas for cooking and built-in wall cupboards, all of these elements provide a window into the household routines and domestic arrangements of earlier generations.

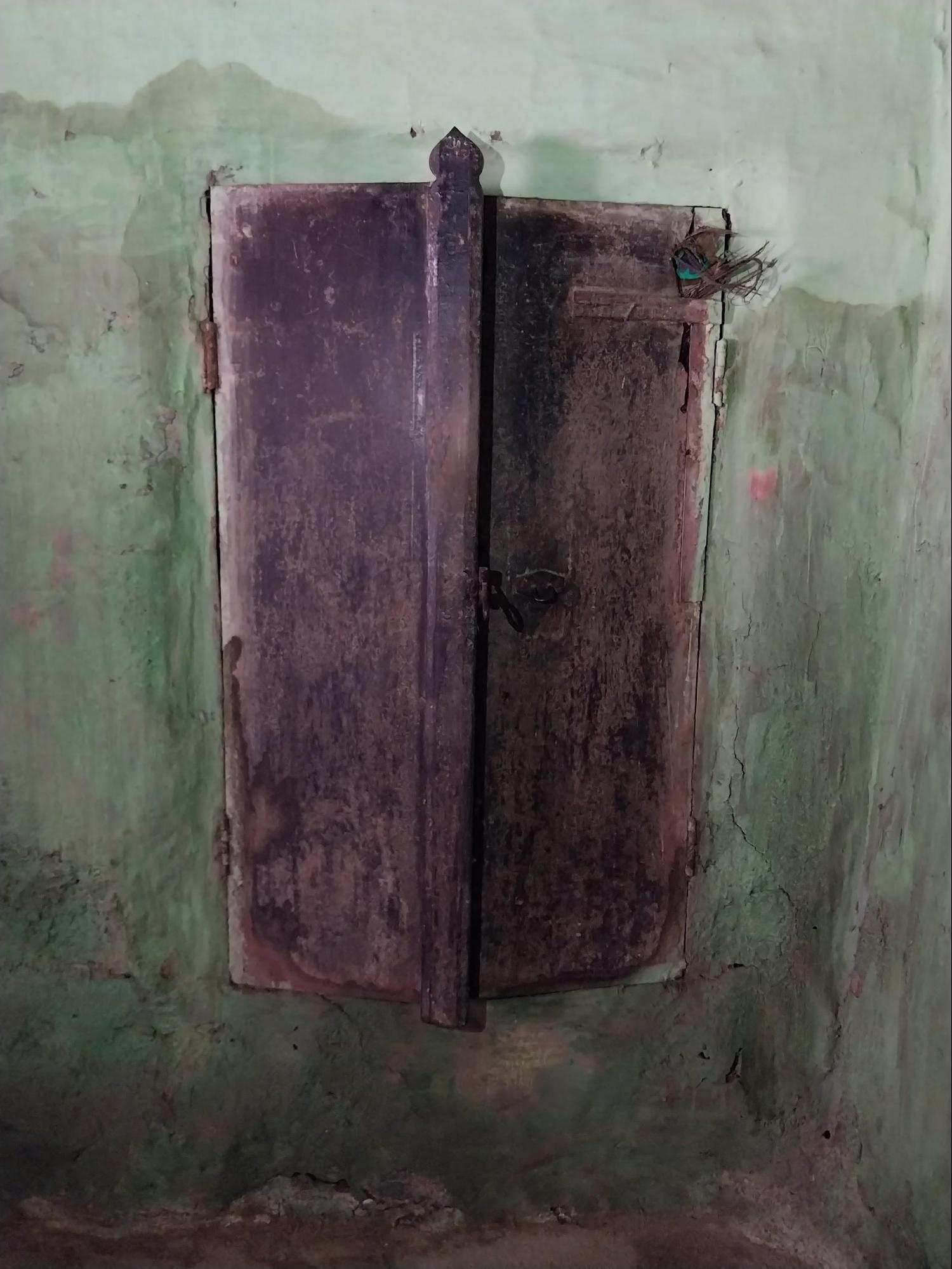

A 1960s Bungalow in Datta Galli

In the quiet locality known as State Bank Colony in Kolhapur City lies Datta Galli, a small lane that houses a notable single-story residence with a terrace. This property, spanning approximately 7000 sq ft., was constructed around 1961 in what was then considered a new urban development area of Kolhapur. Though renovated in 2001 with updates to the bathroom, kitchen, and other areas, the house still keeps much of its original character.

The home is located in a peaceful residential area where trees line many of the streets, creating a pleasant atmosphere for residents.

The neighborhood has a distinctive layout with intersecting lanes that create an organized pattern of homes. Each residence, including this one, is a single-family detached dwelling, standing independently without shared walls.

The architectural character of the building is distinctive. The house was originally built in the 1960s using a combination of wood and stone. It followed a load-bearing structural system, which means the weight of the building is supported by its walls rather than a framework of columns and beams. Over time, renovations introduced new materials, such as plaster and cement, but the wooden elements were preserved to maintain some of the original character.

Inside, the floors are tiled, while the area near the front yard has pavement blocks. One room, now used for storage, still has parts of the original stone construction and contains some furniture from that era.

The facade of the residence follows a symmetrical elevation, with doors and windows aligned at consistent heights. However, an interesting deviation from conventional layouts is the entrance door’s placement at the corner of the building rather than centrally positioned. This stands out because the main structure is centrally located on the plot, with a front lawn, a garage or parking area, and utility spaces arranged along the sides.

Notably, the architectural style of this residence demonstrates both departures from and continuities with traditional building methods, which is evident in the design of the doors. The doors of the residence are not uniform when it comes to their design, but most doors are constructed using wood and follow both contemporary and traditional frameworks.

As mentioned above, inside the storeroom of the home, some historical elements remain untouched. One historical element is the original wooden door, which is similar to those commonly used in older homes in the area. Unlike modern locking systems, this door still uses a chain lock, which was a practical security solution in earlier times.

The doors throughout the residence feature different designs corresponding to the function of the spaces they serve. Interior doors are typically wooden, while exterior doors are made of metal or iron.

Thoughtful architectural details extend to functional hardware elements throughout the residence.

The windows of the home generally follow a more contemporary design, featuring a sliding mechanism.

Chajjas extend over the windows, providing protection from the weather, decorated in ways that add to their appearance. These decorative elements show careful craftsmanship.

Above the chajja, a parapet wall extends outward, offering extra shade and helping to keep the space cooler. Painted in a soft peach color, it has a decorative design with a central arch that adds symmetry to the building.

The interior of the home shows a practical approach to living with select decorative touches. The open main hall has no supporting columns and features a false ceiling.

Recent renovations have modernized the kitchen while maintaining an open connection to adjacent spaces.

The flooring throughout the main living areas utilizes materials that were characteristic of mid-to-late 20th-century urban Indian homes.

Another element in the residence that reflects past decorative practices is an unusual ornamental piece.

When it comes to the exteriors, the property shows thoughtful division of spaces, with clear boundaries defining different functional areas. Both structural elements and natural features help create these distinct zones.

Within the property, additional barriers create a hierarchy of spaces, guiding movement and establishing purpose for each area.

Vertical connections between different levels are provided through simple functional elements.

The roofing system unifies the main living spaces while differentiating utility areas. Utility spaces, such as the storeroom, have different roofing materials, subtly signaling their supporting role within the property.

The property includes several supporting spaces that are intentionally arranged to remain separate from the main living areas while serving transitional functions.

Utility areas are strategically positioned to support household functions while remaining separate from primary living spaces.

Beside and behind the main house, additional space supports storage and utility functions essential for everyday living.

Sources

Department of Tourism Maharashtra. Panhala. Department of Tourism Maharashtra.https://maharashtratourism.gov.in/fort/panha…

India Netzone. Architecture of Panhala Fort. India Netzone. https://www.indianetzone.com/architecture_pa…

Kolhapur Tourism. Shalini Palace. Kolhapur Tourism: Destination Kolhapur. https://www.kolhapurtourism.org/our-destinat…

Museums of India. Town Hall Museum. https://shop.museumsofindia.org/index.php/no…

Nikhil Inamdar. 2017. Kopeshwar: Unearthing Maharashtra’s Khajuraho. Peepul Tree Stories. https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindi…

Priya Kandalkar. 2022. Architecture of Indian Cities- Kolhapur- Roots of Heritage. Pune Research World: An International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, Vol 7, No. 2. Accessed on April 22, 2025.http://puneresearch.com/media/data/issues/65…

Rethinking The Future. Architecture of Indian Cities- Kolhapur- Roots of Heritage. Rethinking The Future. https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/rtf-fre…

Sandhya Kumar. Museums of the World: Chhatrapati Shahu Palace. Rethinking The Future. https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/travel-…

Shraddha Hudale. Kopeshwar temple, Khidrapur. Rethinking The Future.https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/case-st…

TNN. 2017. Kopeshwar Temple: A hidden 12th century relic. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kol…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.