KOLHAPUR

Language

Last updated on 22 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Language has played a pivotal role in shaping India’s social and political landscape, with significant moments such as the States Reorganization Act of 1956, which reorganized the country’s states along linguistic lines. Kolhapur, previously part of the Bombay Presidency, became part of Maharashtra in 1960 following the reorganization of Bombay State, based on Marathi being the most widely spoken language in the district. The variety of Marathi spoken in Kolhapur, however, differs from the standard form and is often referred to as Kolhapuri Marathi. It is marked by specific lexical choices, pronunciation patterns, and sentence structure that give it a distinct rhythm.

The district is also home to multiple speech communities (a group of people who use and understand the same language or dialect), each maintaining its own linguistic practices. Languages such as Hindi, Urdu, Kannada, and Lamani are also spoken in the region, along with localized varieties like Kolhapuri Hindi, which has emerged through sustained contact between communities.

Linguistic Landscape of the District

At the time of the 2011 Census of India, Kolhapur district had a total population of approximately 38,76,001. Of this population, 89.16% reported Marathi as their first language. This was followed by Hindi (3.85%), Urdu (2.70%), and Kannada (1.97%). Other languages spoken as mother tongues included Marwari (0.50%), Sindhi (0.45%), Gujarati (0.33%), and Telugu (0.32%). Smaller linguistic groups included the Vadari and Lamani/Lambadi, which accounted for 0.10% each.

Language Varieties in the District

Kolhapuri Marathi

Kolhapuri Marathi is a regional variety of Marathi spoken in the Kolhapur district of Maharashtra. It belongs to the broader Southern Marathi linguistic cluster, but is marked by features that set it apart from the varieties spoken in Pune and other parts of the state. Known for its distinct rhythm, stress pattern, and expressive style, Kolhapuri Marathi carries a linguistic character that many describe as bold, playful, and raw.

Speakers often describe Kolhapuri Marathi as being open and unfiltered, with a tone that feels humorous, creative, and direct. Words that may be considered strong or even offensive in other regions are frequently used here in friendly and informal contexts. These include expressions borrowed from Konkani, Kannada, and surrounding varieties, showing how the variety has evolved through contact and local culture. Some commonly used words include:

|

Word |

Meaning |

|

ḍāmbis |

Someone who thinks they’re clever |

|

ṭagyā |

A large or burly person |

|

khamkyā |

A strong, influential person |

|

uchāpati |

Someone who tends to stir up trouble |

Multiple terms are used for simple objects—for instance, “head” may be referred to as ḍoskǝ, ṭaɭǝkǝ, or ṭakur, depending on context or speaker.

A distinctive feature of Kolhapuri Marathi is its extensive use of onomatopoeia, words that imitate sounds or emphasize the action they describe:

- bakābakā lāthā hānlyā – to kick someone hard (bakābakā imitates the kicking sound)

- fassadishi vadlǝ – to snatch something quickly (fassadishi mimics the quick motion)

- kachākachā maṭanǝ hānlǝ – to eat mutton quickly and noisily (kachākachā evokes the sound and mess of fast eating)

Kolhapuri Marathi includes many alternate words for familiar Marathi terms, often used interchangeably:

|

Marathi |

Kolhapuri Marathi |

Transliteration |

English Meaning |

|

लग्न (lagna) |

लगीन |

lagīn |

Marriage |

|

वेडं (veḍā) |

येडं |

yeḍā |

Mad / foolish |

|

काकडी (kākḍī) |

वळुकं |

vaɭukǝ |

Cucumber |

|

बादली (bādli) |

बारदी |

bārdi |

Bucket |

|

वडील (vaḍīl) |

बा |

bā |

Father |

|

मुलगा (mulgā) |

पोरगा / ल्योक |

porgā / lyok |

Boy |

|

मुलगी (mulgī) |

पोरगी |

porgī |

Girl |

|

सासू (sāsu) |

इन / यीन |

in / yīn |

Mother-in-law |

|

सासरा (sāsra) |

इवाय / इवायई |

ivāyǝ / ivāyǝi |

Father-in-law |

|

झोप काढली (zhop kāḍhli) |

ताणून दिली |

tāṇūn dili |

Took a nap |

|

खूप जोरात (khūp jorāt) |

तर्राट |

tarrāṭ |

Very fast |

|

खूप भारी (khūp bhārī) |

वांड / काटा किर्र / नाद खुला |

vānd / kāṭā kirr / nād khuɭā |

Amazing / excellent |

One of the most noticeable aspects of Kolhapuri Marathi is its distinct intonation and speech rhythm, especially in casual conversation. The tone is said to carry a rather melodic tone, with a rising pitch at the end of sentences.

In the Kolhapuri speech, the short 'a' vowel at the end of words is often fully pronounced, rather than being dropped or reduced as in many other regional varieties.

Extra /u/ Sounds. Some nouns in Kolhapuri Marathi include an additional ‘-u’ sound in the middle or end of the word that isn’t present in other varieties of Marathi.

|

Marathi |

Kolhapuri Marathi |

Transliteration |

Meaning in English |

|

बोकड (bokaḍ) |

बोकुड |

bokuḍ |

Male goat |

|

दगड (dagaḍ) |

दगुड |

daguḍ |

Stone |

|

कागद (kāgad) |

कागुद |

kāgud |

Paper |

Use of /-i-/. In Kolhapuri Marathi, some verbs get an extra “i” sound in the middle, especially when a sentence is about making someone do something (what linguists call a “causative” verb).

|

Marathi |

Kolhapuri Marathi |

Transliteration |

Meaning in English |

|

वाचलं (vāchlǝ) |

वाचिवलं |

vāchivlǝ |

To read |

|

झोपवलं (zopavalǝ) |

झोपिवलं |

zopivlǝ |

To make someone sleep |

|

घालवलं (ghālavlǝ) |

घालिवलं |

ghālivlǝ |

To send / give away |

|

बसवलं (basavalǝ) |

बसिवलं |

basivlǝ |

To make someone sit |

When verbs begin with an ‘o’ sound in other varieties of Marathi, it often

shifts to a ‘v’ sound in Kolhapuri Marathi. This can be seen in the words in the following table:

|

Marathi |

Kolhapuri Marathi |

Transliteration |

Meaning in English |

|

ओढलं (odhlǝ) |

वढलं |

vadhlǝ |

To pull |

|

ओरबडलं (orbādlǝ) |

वरबडलं |

varbādlǝ |

To scratch / snatch |

|

ओरडलं (oradlǝ) |

वरडलं |

varadlǝ |

To shout |

In rural parts of Kolhapur, it is observed that speakers often use /n/ (न) in place of /ɳ/ (ण), which is usually used in other varieties of Marathi. Sometimes, both are used interchangeably depending on the speaker.

|

Marathi |

Kolhapuri Marathi |

Transliteration |

Meaning in English |

|

मी पाणी प्यायलो (mī pāṇī pyāyalo) |

म्यां पानी प्यालो |

myā pāṇī pyālo |

I drank water |

|

इथे लोणी होते (ithe loṇī hote) |

हितं लोनी होतं |

hitǝ loni hutay |

Butter was kept here |

While Kolhapuri Marathi shares roots with Marathi, the grammatical structure has its own special twists and turns that make it stand out.

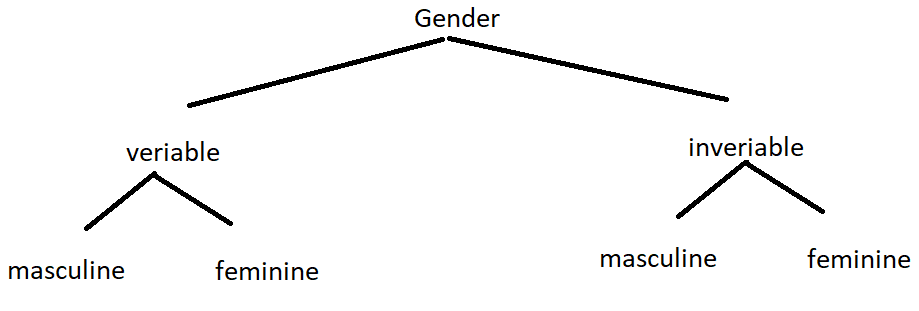

In the Marathi spoken more widely beyond Kolhapur, verbs change their endings based on the gender of the person in terms of the subject. For example, the verb ending for a male is different from the verb ending for a female. The verb also changes for number (singular/plural), tense, and case. However, in Kolhapuri Marathi, this isn’t the case, and it is relatively more gender-neutral, as can be seen below:

|

Marathi Words |

Kolhapuri Marathi |

Meaning in English |

|

mi yeto. (male) mi yete. (female) |

mi yeto. (male) mi yeto. (female) |

I come. |

|

mi jāto. (male) mi jāte. (female) |

mi jāto. (male) mi jāto. (female) |

I go. |

|

mi karto. (male) mi karte. (female) |

mi karto. (male) mi karto. (female) |

I do. |

|

tu kadhi ālās? (male) tu kadhi ālis? (female) |

tu kadhi ālās? (male) tu kadhi ālās? (female) |

When did you come? |

|

to sobat yetoy. (male) ti sobat yetiye.(female |

te sobat yetayǝ. (male) te sobat yetayǝ. (female) |

He comes along. She comes along. |

As one can observe, in the Kolhapuri variety of Marathi, the pronoun ‘te’, which usually means ‘it’, is often used instead of ‘he’ or ‘she’ to refer to both males and females. This is different from the commonly understood Marathi, where separate words like ‘to’ (he) and ‘ti’ (she) are used. For example:

In Kolhapuri Marathi, ‘te ghari ālǝ’ (It came home), can refer to either a boy or a girl. Here, ‘te’ is used instead of ‘he’ or ‘she’, making it a neutral pronoun that replaces both.

One special feature of Kolhapuri Marathi is the use of the suffix “shyānə” (श्यानं) to show that one action happened right after another.

This suffix is added to the first verb in a sentence to show that it happened before the second. It's used a lot in daily conversation to link events. For example:

|

Kolhapuri Marathi |

Meaning |

|

शाळेला जाऊनश्यानं घरी येतो (shāɭelā jāunshyānə ghari yeto) |

"Goes to school and then comes home" |

|

म्या जेवूनश्यानं झोपलो (myā jevunshyānə zoplo) |

"Ate (a meal) and then went to sleep" |

So instead of using two separate sentences, one for each action, “shyānə” connects them into a smooth chain. This keeps the sentence compact, natural, and shows a sense of order and timing.

In most varieties of Marathi, when describing things that used to happen regularly in the past, the past tense is used. For example, "He used to study every day" would use the past habitual form.

But in Kolhapuri Marathi, there's something interesting: speakers often use the simple future tense instead to talk about old habits or repeated actions in the past. For example:

|

Marathi |

Kolhapuri Marathi |

Meaning |

|

राहुल रोज अभ्यास करायचा / करत असे (rāhul roj abhyās karāychā / karat ase) |

ह्यो रावल्या रोजच्याला अभ्यास करणार बघा (hyo rāvlā rojchyālā abhyās karanār bagā) |

"Rahul used to study every day" |

So, instead of saying “used to study” using a past form, Kolhapuri speech borrows the future form ("will study") to describe that same repeated, past behavior. This shift perhaps gives the sentence a kind of narrative liveliness, as if the past action still feels current or vivid in memory.

To talk about something that has just happened, Kolhapuri Marathi often adds the suffix “-yā” (या) at the end of the verb. This shows that the action is complete and recent. For example:

|

Marathi |

Kolhapuri Marathi |

Meaning |

|

मी हे जिंकले (mī he jinkle) |

म्या हे जिंकलया (myā he jinklayā) |

"Have won this" |

|

त्याने हे वाचले (tyāne he vāchle) |

त्यानं हे वाचलया (tyānǝ he vāchlayā) |

"Has read it" |

|

दाजिने तुम्हाला बोलावले (dājine tumhālā bolāvle) |

दाजिनं तुम्हास्नी बोलिवलया (dājinǝ tumhāsni bolivlayā) |

"Has called you" |

In Kolhapuri Marathi, people use "lelyo" (for masculine) or "lyāli" (for feminine) to show that something had already happened in the past. For example:

|

Marathi |

Kolhapuri Marathi |

Meaning |

|

मी घरी गेलो होतो (mi ghari gela hota) |

म्या घरी गेलेल्यो (myā ghari gelelyo) |

"Had gone home" |

|

ती झोपली होती (ti zopli hoti) |

ती झोपल्याली (ti zoplyāli) |

"Had slept" |

To talk about something that will happen, Kolhapuri Marathi often adds “-yāl” (याल) to verbs, making the future action very clear. For example:

|

Marathi |

Kolhapuri Marathi |

Meaning |

|

आता पाहुणे येतील (ātā pāhuṇe yetīl) |

आता पावनं येत्याल (ātā pāvnǝ yetyāl) |

"Guests will arrive, won’t they?" |

|

माझी मुलं शाळेत जातील (mājhī mulaṃ shāḷet jātīl) |

माझी मुलं शाळेमंदी जात्याल (mājī mulā sāɭemandi jātyāl) |

"Children will go to school" |

|

ते रात्री येतील (te rātrī yetīl) |

ते रातच्याला येत्याल (te rāṭachyālā yetyāl) |

"They will come at night" |

Kolhapuri Marathi adds the suffixes "-sā" (सा) or "-ti" (ती) to verbs to show politeness or respect, often in conversation with elders or figures of authority.

|

Marathi |

Kolhapuri Marathi |

Meaning |

|

मास्टर बाहेर गेले आहेत (māstar bāher gele āhet) |

मास्टर बाहेर गेलेती (māstar bhāyer geleṭi) |

"The teacher has gone out" |

|

तुम्ही काय म्हणता? (tumhī kāy mhaṇtā?) |

तुम्ही काय म्हणतसा? (tumhī kāy mhaṇtṣā?) |

"What are you saying?" |

In many varieties of Marathi, “madhye” (मध्ये) is usually used to mean "in" or "inside." In Kolhapuri Marathi, “mandi” (मंदी) is often used instead, especially in rural areas. For example:

|

Marathi |

Kolhapuri Marathi |

Meaning |

|

शाळेमध्ये (shāɭemadhye) |

शाळेमंदी (sāɭemandi) |

"In school" |

|

घरामध्ये (gharāmadhye) |

घरामंदी (gharāmandi) |

"At home" |

|

मंडईमध्ये (maṇḍaimadhye) |

मंडईमंदी (maṇḍayimandi) |

"In the market" |

Reduplication is simply the repetition of the same word to make a point stronger or give it more emphasis. In the Kolhapuri linguistic variety of Marathi, reduplication is quite common. For instance, the sentence: ‘Māzǝ kām zatpat zatpat zālǝ.’ This translates to ‘My work got done quickly.’ Here, the word ‘zatpat’, meaning fast, is repeated.

Kolhapuri Marathi is full of idioms and phrases that come from local culture, especially farming, wrestling (a big sport in Kolhapur), and traditional rural life. Some common idioms and sayings are as follows:

|

Phrase |

Transliteration |

Literal Meaning |

Used To Mean |

|

गावऱ्यांचं बोल |

gāvrāncha bol |

"Villager’s talk" |

Speak plainly; don’t overcomplicate |

|

माझा लंगोट पक्का आहे |

mājhā laṅgoṭ pakkā āhe |

"My loincloth is tied tight." |

Fully prepared; ready for anything (esp. in wrestling) |

|

रिक्षा फिरवू नको |

rikshā phirvu nako |

"Don’t drive a rickshaw around." |

Stop wasting time or stalling; get to the point |

These expressions are deeply rooted in local imagery; the langoṭ (loincloth) reference comes from wrestling culture, while the rickshaw one reflects urban hustle. They’re witty, direct, and full of regional flavor.

Kolhapuri Marathi often conveys respect and familiarity not through strictly formal language, but through the use of kinship terms and regional discourse markers. These elements reflect the community-based, orally rich nature of the region’s communication.

In place of formal honorifics like "sāheb" or "rāv" (common in Puneri or urban Marathi), speakers may use kin terms like दादा (dādā, elder brother) or मामा (māmā, maternal uncle). These are used broadly — not just for relatives, but for older men, friends, or even strangers, depending on the tone and context. This use of kinship-based reference adds a layer of warmth and informality, while still signaling respect. For example:

- काय दादा? (kāy dādā?) – “What’s going on, brother?”

- मामा, इकडं बघा! (māmā, ikaḍaṁ baghā!) – “Uncle, look here!”

Kolhapuri Marathi is also full of conversational markers and fillers like:

- "रे" (re) – often used with men or boys

- "गं / गा" (ga) – used with women or girls

- "बाऽ" (bā) – often added for effect or flow

- "राव" (rāv) – a friendly emphasis word, kind of like “man” or “boss”

These don’t translate literally but are used to spice up sentences, maintain rhythm, and build a connection between speakers. Some examples include:

|

Kolhapuri Phrase |

Transliteration |

Meaning in English |

|

काय रे, काय चाललंय रे बाप्पा? |

kāy re, kāy chāllalay re bāppā? |

"Hey, what’s going on, man?" |

|

अगं बसा गा! |

agaṁ basā gā! |

"Hey, sit down!" (spoken to a woman) |

|

माझं काम धडाक्याने चाललंय रे राव! |

mājhā kām dhaḍākhyāne chāllalay re rāv! |

"My work is going on with a bang, man!" |

|

तो बोललाय राव! |

to bolllāy rāv! |

"He’s said it, man!" |

|

शाळेला जातोस का रे राव? |

shāḷelā jātos kā re rāv? |

"Going to school, man?" |

These phrases, in many ways, reflect a direct yet affectionate tone, typical of Kolhapuri interactions, which locals describe as honest, humorous, and never dull.

Kolhapuri Hindi

While Marathi is the dominant language in Kolhapur, a regional variety of Hindi, often referred to as Kolhapuri Hindi, has emerged through intense language contact between Hindi and Marathi speakers. According to the 2011 Census, around 3.85% of the district's population speaks Hindi as their mother tongue. However, the Hindi spoken in this region does not exactly resemble the Hindi of northern India. Instead, it has developed its own features, influenced by local pronunciation, sentence structure, and vocabulary usage.

Kolhapuri Hindi often shows signs of grammatical and lexical borrowing from Marathi. This means that both sentence patterns (syntax) and vocabulary (lexicon) are influenced by the local dominant language.

For example, speakers may use Marathi sentence endings or question formats while speaking in Hindi. Tag questions in Marathi often use the word “ना” (nā) to soften a question or suggest agreement. This same word is inserted into Hindi sentences in Kolhapur, replacing Hindi forms like “क्या?” (kyā?). Some examples include:

- Hindi: वो किताब ला दो (wo kitāb lā do)

Kolhapuri Hindi: वो पुस्तक यहाँ लेके आओ (wo pustak yahān leke āo)

→ “Bring that book here.”

(Note the use of pustak instead of kitāb, and yahān leke āo instead of lā do) - Hindi: वो बहुत अच्छा है (wo bahut acchā hai)

Kolhapuri Hindi: वो कितना चांगला है ना? (wo kitnā chāṅglā hai nā?)

→ “He’s so good, isn’t he?”

(चांगला is a Marathi word for “good”; ना adds a tone of agreement) - Hindi: आप यहाँ आएंगे क्या? (āp yahān āenge kyā?)

Kolhapuri Hindi: आप यहाँ आएंगे ना? (āp yahān āenge nā?)

→ “Will you come here?”

(ना is used here just like in Marathi to form a yes-no question)

This kind of “hybrid” structure is common, especially in informal or semi-formal settings, and reflects the natural blending of languages in a multilingual space.

Speakers in Kolhapur often switch between Hindi, Marathi, and English—a practice known as code-switching (the alternation between languages in a single conversation or even within a sentence).

This mixing is particularly common in casual or informal conversations. For example:

"Kal kya karoge? Bazaarme jaane ka kaahi plan aahe kā?"

(“What will you do tomorrow? Is there any plan to go to the market?”)

Here, we see Hindi and Marathi blended seamlessly. The sentence starts in Hindi and shifts into Marathi halfway, reflecting a hybrid linguistic environment.

Kolhapuri Hindi also displays some phonological influence (sound-based influence) from Marathi. A few features include:

- Stronger retroflex sounds: Letters like ट (ṭ) and ड (ḍ) are pronounced more distinctly than in northern Hindi. Retroflex sounds are made by curling the tongue back, and Marathi gives them a sharper quality.

- Lengthened vowels: Short vowel sounds in Hindi may be pronounced longer in Kolhapuri speech.

- Reduced nasalization: Nasal sounds like “ँ” (as in मैं /ma͂i/, “I”) are less prominent than in other varieties of Hindi.

These shifts likely give Kolhapuri Hindi a sound that is phonetically closer to Marathi, even if the vocabulary is mostly Hindi.

Speakers of Kolhapuri Hindi sometimes translate Marathi idioms directly into Hindi, rather than using idioms from Hindi. This often results in literal-sounding phrases that are meaningful locally, even if they feel unusual outside the region. For example:

|

Marathi Idiom |

Literal Hindi Translation |

Hindi Equivalent |

|

तोंडावर पडलं (toṇḍāvar padla) |

मुँह पर गिरा (munh par girā) |

मुँह के बल गिरा (munh ke bal girā) |

This kind of idiomatic structure reflects how regional imagery and meaning are preserved, even across languages.

Lamani Language

Lamaani, also known as Lambani, Lambadi, Gour Boli, Gormati, or Banjari, is a language spoken by a large community spread across various regions of India. It is spoken by the Banjara or Laman community, originally from the Mewar region of Rajasthan. Over time, this community migrated to various parts of India in search of trade and employment, leading to a wide geographical spread. Today, Lambani speakers can be found in Maharashtra, Karnataka, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, and West Bengal, with smaller populations in other states.

Lamani does not have a native script (original writing system), which has shaped how the language is used and preserved. Instead of writing in their own script, speakers have adapted the writing systems of surrounding regional languages. In Maharashtra, for example, they use the Devanagari script (used for Marathi and Hindi), while in Karnataka, the Kannada script is used.

Lamani has 6 vowels:

a, e, i, o, u (and longer versions like ā, ī, etc.)

Long vowels are usually not used at the end of words.

There are 32 consonants, many like those in Marathi.

But some sounds, like the Marathi "थ" (/th/ with a breath), do not exist in Lamani.

Also, Lamani uses nasal sounds (like "n" in "song"), but changing them doesn’t usually change the word’s meaning. Aspirated sounds (with a breathy sound) appear mostly at the start of words.

Lamani shows a fascinating blend of its own vocabulary and forms borrowed from languages like Marathi and Hindi. This blending is most noticeable in everyday words, terms for family, the body, colours, food, and numbers. Many of these look and sound quite similar across all three languages, showing how close contact and migration have shaped the language.

In terms of kinship and pronouns, Lamani uses words that are nearly identical to Marathi and Hindi. For instance, sāsu means ‘mother-in-law’ in all three. The word for father in Lamani, bā, is closely related to bābā or vadil in Marathi and pitāji in Hindi. Even the second-person singular pronoun tu is the same across the three languages.

|

Lamani |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

sāsu |

sāsu |

sās |

mother-in-law |

|

bā |

bābā / vadil |

pitāji |

father |

|

dhani |

dhani / navarā |

pati |

husband |

|

tu |

tu |

tum |

you |

Words for body parts follow a similar pattern. In many cases, there is almost no difference in form; for example, dāt for ‘tooth’, hāt for ‘hand’, and gāl for ‘cheek’ are the same in Lamani and Marathi, and very close in Hindi too. This suggests a strong set of shared roots or long-term borrowing between the languages.

|

Lamani |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

hot |

oth |

hoth |

lips |

|

dāt |

dāt |

dānt |

tooth |

|

hāt |

hāt |

hānth |

hand |

|

gāl |

gāl |

gāl |

cheek |

|

anguthā |

angathā |

anguthā |

thumb |

|

pet |

Pot |

pet |

stomach |

|

kapāɭo |

kapāɭ |

sir |

forehead |

|

ṭāng |

Pāy |

ṭāng |

leg |

The same goes for colours. Lamani’s haro (green) and niɭo (blue) are very close to hirwā and niɭā in Marathi and harā, nilā in Hindi. The small vowel differences at the end don’t change the meaning, but they do reflect local phonological patterns.

|

Lamani |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

haro |

hirwā |

harā |

green |

|

niɭo |

niɭā |

nilā |

blue |

Food vocabulary is especially rich in borrowed or shared forms. Words like kāndo (onion), seb (apple), and santra (orange) are consistent across the three languages. A few items, like angur (grapes), also show influence from Marathi, which uses jāmbhuɭ, reflecting regional variety even within a shared root.

|

Lamani |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

kāndo |

kāndā |

pyāj |

onion |

|

muɭo |

muɭā |

muɭi |

radish |

|

angur |

jāmbhuɭ |

angur |

grapes |

|

santra |

santra |

santra |

orange |

|

seb |

sapharchandǝ |

seb |

apple |

|

āṭo |

pith |

āṭā |

flour |

|

nimbu |

limbu |

nimbu |

lemon |

|

ālu |

baṭāṭā |

ālu |

potato |

|

bhindā |

bhendi |

bhindi |

lady finger |

In numbers too, Lamani keeps very close to both Marathi and Hindi, particularly for the basic counting numbers. Words like ek (one), ʧār (four), and sāt (seven) are essentially the same. For numbers above twenty, Lamani uses a compounding system: wisan ek for twenty-one, wisan di for twenty-two, and so on.

|

Lamani |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

ek |

ek |

ek |

one |

|

ʧār |

ʧār |

ʧār |

four |

|

nav |

nau |

nau |

nine |

|

sāt |

sāt |

sāt |

seven |

|

das |

dahā |

das |

ten |

|

sǝu |

shambhar |

sǝu |

hundred |

|

vis |

vis |

bis |

twenty |

Ordinal numbers are also easy to form. In Lamani, adding -ne to a cardinal number makes it ordinal. For instance, ekne is ‘first’, dine is ‘second’, and tinne is ‘third’. General vocabulary also reflects a strong Marathi and Hindi influence, with many everyday nouns being identical or nearly so.

|

Lamani |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

phul |

phul |

phul |

flower |

|

pankhā |

pankhā |

pankhā |

fan |

|

pāɳi |

pāɳi |

pāni |

water |

|

ābhaɭ / ābhaɭo |

ābhaɭ |

ākāsh |

sky |

|

mor |

mor |

mor |

peacock |

|

ghodā |

ghodā |

ghodā |

horse |

|

somwār |

somwār |

somwār |

Monday |

|

rāt |

rātrǝ |

rāt |

night |

Lamani nouns follow a pattern that shows gender (male or female), number (singular or plural), and case (how the noun functions in the sentence, like subject or object). There is no third gender category (neuter), which is different from many other regional languages.

In Lamani, the general form of a noun is:

Noun stem + gender + number + case suffix

(case suffix = small ending added to show the noun's role in a sentence)

Some nouns use the same root but change the ending vowel to show gender. For example:

|

Masculine |

Feminine |

Meaning in English |

|

ghodā |

ghodi |

horse |

|

betā |

beti |

boy/girl |

In Lamani, plural forms (more than one) are often shown through the verb or number word in the sentence, rather than changing the noun itself. This is especially true when the noun is the subject. In such cases, the noun form stays the same, and the listener understands it’s plural based on context.

In other cases, Lamani uses three ways to show plurals:

- Adding a suffix (a small word-ending)

- Repeating the noun (called reduplication)

- Removing part of the original word

|

Singular |

Plural |

Method Used |

Gloss |

|

betā |

betābetā |

Reduplication |

boy → boys |

|

sāsu |

sāsuo |

Adds suffix ‘-o’ |

aunt → aunts |

|

telǝwālo |

telǝwāl |

Ending removed |

oilman → oilmen |

Lamani also uses common endings from other languages to form agent words (called agentive suffixes). For example, wala (male) and wali (female) are added to describe someone doing a job or activity—like telwala = “oil seller.”

Pronouns (words like I, you, they) in Lamani don’t show gender, but they do show singular/plural. The basic structure is:

Pronoun stem + case suffix

|

Singular |

Plural |

Meaning in English |

|

ma |

ham |

I – we |

|

tu |

tam |

you – you all |

Lamani also uses ekmek for “each other,” just like in Marathi. This shows how closely the two languages are related in structure.

Verbs in Lamani change depending on who is doing the action and when it happens. This process is called conjugation (changing a verb to show tense, number, or gender). For example, jo means “to go,” but its form will change depending on the speaker or time.

|

Base Verb |

Present Tense (3rd person) |

Explanation |

|

jo |

jāwa |

“he/she goes” – adds ‘w’ |

|

baga |

bagawa |

“throws” – adds ‘w’ |

|

lu |

luwa |

“wipes” – adds ‘w’ |

In the past tense, Lamani uses -y after verbs that end in a, u, or o:

|

Verb |

Past Tense |

Meaning |

|

ā |

āy, āyo |

came |

|

so |

soy, soyo |

slept |

|

cu |

cuy, cuyo |

leaked |

There are a few compound verbs in Lamani, such as:

|

Normal verb |

Compound verb |

Meaning in English |

|

Jo (to go) |

pad jo wad jo so jo dhās jo le jo |

To fall down To fly away To fall asleep To run away To take away |

|

lā (to take/ to accept) |

Ker lā rām lā |

To do To play |

|

dā (to give) |

bhānd da |

To tie |

Sources

Aaditya Kulkarni. 2017. Present Progressive Verb Form in Kolhapuri Marathi: A Case of Grammaticalization? Vol. 1 no. 2. Jadavpur Journal of Languages and Linguistics.

Census of India. 2011. Language Atlas of India. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India.https://language.census.gov.in/showAtlas

George Yule. 2020. The Study of Language. 7th ed. Cambridge University Press.

Grierson, G. A. 1907. Linguistic Survey of India, Volume 7. Survey of India.https://archive.org/details/LSIV0-V11/LSI-V7…

Jayashree Patil. 2014. Study of the Phonology of Lamani Language Spoken in Pune (Master's thesis). Deccan College Post-Graduate & Research Institute, Pune.

Kishor R. Gavade , Vikram K. Hankare, Sushma S. Desai. 2023. Dialect Differentiation of Standard Marathi Language with Comparison to Kolhapur Region Marathi Language. IJRAR. Vol 10, Issue 2.

Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. 2011. Census of India 2011: Language Census. Government of India.https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/ca…

R.L. Trail. 1968. Lamani: Phonology, Grammar and Lexicon (Doctoral dissertation). University of Poona.https://www.sil.org/resources/archives/9360

Randhir Shinde. 2017. Kolhapur Has Its Own Linguistic Style कोल्हापुरी बोलीचं वैशिष्ट्य. Maharashtra Times.https://marathi.indiatimes.com/editorial/art…

Sambhaji Jadhav. 2019. Aspect in Marathi in a Cross-dialectal perspective. 41st International Conference of Linguistic Society of India (ICOLSI- 41) at IGNTU, Amarkantak.https://sdml.ac.in/pdfs/aspect-in-marathi.pdf

Sonal Kulkarni-Joshi & Manasi Kelkar. 2021. Synchronic Variation and Diachronic Change in Dialects of Marathi. Research Gate.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354…

Sonali Kulkarni-Joshi. (2023). Variation and Change in Dialects of Marathi: A Social-Dialectological Approach. In: Chandra, P. (eds) Variation in South Asian Languages. Springer, Singapore.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1149-3_9

Wikipedia contributors. Kolhapuri. Wikipedia.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kolhapuri

Last updated on 22 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.