Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- The Legend of Kolhasur and the Abode of Mahalakshmi

- Satavahana Rule and the Spread of Buddhism

- Early Chalukya Consolidation and the Rise of Temple Architecture

- Rashtrakuta Expansion and Samangad Fort

- Western Chalukyas and Campaigns in the Konkan

- The Shilaharas of Kolhapur

- Gandaraditya I and the Consolidation of Shilahara Rule

- Bhoja II and the Construction of the Kopeshwar Mandir

- Construction of the Panhala Fort

- The Yadavas of Devagiri and the End of Silahara Rule

- Medieval Period

- Bahmanis

- Adil Shahi Control and the Fortification of Panhala

- Marathas

- The Panhala Fort under the Marathas

- The Famous escape of Shivaji from Panhala, 1660

- Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj

- Maharani Tarabai

- Formation of the Kolhapur Kingdom

- Sambhaji II and Jijabai

- Kolhapur as a Princely State

- Colonial Period

- Kolhapur’s Status Following the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1818)

- Administrative Decline under Shahaji (Babasaheb), 1821–1838

- The Gadkari Uprising in Kolhapur

- Ramji Shirsat’s Revolt and Local Dissent in Kolhapur (1857)

- The Death of Shivaji VI and Political Unrest in Kolhapur (1866–1883)

- Social Reform and State Development under Chhatrapati Shahu IV (Rajarshi Shahu Maharaj) of Kolhapur (1894–1922)

- Rajaram III and the Final Phase of Princely Rule in Kolhapur (1922–1949)

- Local Print Culture and the Role of Pudhari

- Cultural Production and the Legacy of Mahadev Vishwanath Dhurandhar in Kolhapur

- Post Independence

- Founding of Shivaji University

- Sources

KOLHAPUR

History

Last updated on 17 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Kolhapur district, located in the southwestern part of Maharashtra, has a rich history that stretches back to ancient times. The region is mentioned in the Puranas, and some scholars suggest it may have been referenced by Ptolemy, the 2nd-century Egyptian geographer, though this identification remains debated. Historically, Kolhapur witnessed the rule of several dynasties in succession. The Andhrabhrityas were among the earliest known powers in the region, followed by the Kadambas and the Western Chalukyas. The Rashtrakutas (8th to 10th century CE) rose to prominence afterward, leaving behind significant architectural and cultural influences.

In the following centuries, Kolhapur came under the control of the Shilharas, who fortified the region and contributed to its urban development. They were succeeded by the Devagiri Yadavas, until the Bahmanis (14th to 16th century CE) established dominance. By the 17th century, the Marathas emerged as the region’s most influential force. Among their most notable leaders was Rajmata Tarabai Bhosale, the formidable queen and military strategist. In the early 18th century, during a period of political upheaval, she established Kolhapur as a separate Maratha power center. Her leadership not only shaped the district’s identity but also ensured its lasting significance in Maratha history.

Etymology

The origin of the name Kolhapur is deeply rooted in local legend and centers around the Devi Mahalakshmi, who is regarded to be the presiding deity of the district. According to local tradition, the demon Kolhasur, after his sons were slain by the Devis and Devtas for tormenting people, gave up his asceticism and sought intervention from Mahalakshmi Devi. He requested that she leave the region for a hundred years, during which he carried out various acts of disturbance. Eventually, Mahalakshmi returned, leading to a fierce battle in which Kolhasur was defeated. As he lay dying, he asked that the land be named after him. Thus, the name Kolhapur is believed to derive from ‘Kolha’ (from Kolhasur) and ‘pur’, a Sanskrit word meaning ‘city.’

Historical references to the name also appear in records from the Shilahara dynasty, which ruled the region from the 8th to 12th century CE. Inscriptions from this period mention names like ‘Kshullakpur’, possibly referring to an early phase of Jain monastic life, and ‘Kalapuri’, meaning a city adorned with artistic beauty, especially mandirs. These names appear in stone inscriptions found in ancient Jain mathas and shrines near the Ambabai (Mahalakshmi) Mandir and offer valuable insight into the region’s religious and cultural heritage.

Ancient Period

The Legend of Kolhasur and the Abode of Mahalakshmi

When it comes to the district’s history, Kolhapur’s ancient identity is inseparably tied to the figure of Kolhasur, a powerful asura who, according to long-standing regional tradition, once terrorised the land then known as Karavira. As the story is recounted in local oral histories and lore, it was Mahalakshmi Devi, also called Ambabai, who descended to vanquish Kolhasur after a fierce battle. Before his death, the asura is believed to have pleaded with the goddess that the city bear his name, a wish she granted. From this, the name Kolhapur, or “city of Kolhasur,” is said to have emerged. This story is often cited as the origin of the name Kolhapur and is central to the way Ambabai is understood, as both protector and guardian of the region.

The Mahalakshmi Mandir, situated on the banks of the Panchganga River, remains one of the most visited pilgrimage sites in western India. Regarded as one of the 51 Shakti Peethas, it is particularly significant for communities across Maharashtra, where Ambabai is revered as a kul devi (family deity).

While the present structure of the Mahalakshmi Mandir is believed to have been rebuilt and modified over the centuries, its earliest foundations date back to around the 7th century CE, likely under the patronage of the early Chalukyas.

Satavahana Rule and the Spread of Buddhism

The earliest known political formation to control the region of Kolhapur was the Satavahana dynasty, which ruled over much of the Deccan between the 1st century BCE and the 3rd century CE. During their reign, Kolhapur and the surrounding valleys of the Panchganga River witnessed significant cultural and religious development. The Satavahanas are remembered not only for their administrative organisation but also for their patronage of Buddhism, which flourished in the district.

The colonial district Gazetteer (1886) records the discovery of a large Buddhist stupa during excavations conducted in 1877 in the district. Within this stupa was found an early Brahmi inscription reading, “The gift of Bamha made by Dhamaguta.” While little is known about the individuals named, it is believed that Dhamaguta may have been a local chief or patron of Buddhist practice, active during or shortly after the Mauryan period. The stupa provides the earliest epigraphic evidence of Buddhism in Kolhapur district.

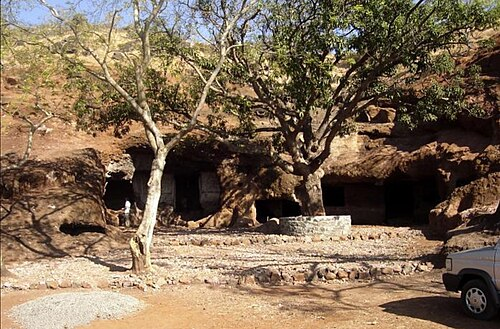

During this time, numerous rock-cut caves were excavated in the basaltic hills near Kolhapur. The Pandavdara Caves, located near Panhala, and the Pohale or Pavala Caves, situated northwest of the city near Jyotiba’s Hill, are attributed to this period. Though local folklore attributes their construction to the Pandavas of the Mahabharata, scholars agree that these were originally Buddhist viharas and chaityas, created as monastic dwellings and prayer halls during the Satavahana era. The architectural features, simple rock-cut benches, water cisterns, and pillared halls, are consistent with Buddhist cave architecture across the Deccan.

Another connection that ties Kolhapur to the Satavahanas comes from the Greek geographer Ptolemy, writing in 150 CE, who in his text mentions a settlement called Hippokura, which many historians identify with Kolhapur. Historian R.G. Bhandarkar further suggested that Kolhapur at this time was ruled by a Satavahana king named Vilivayakura, possibly the same figure that Ptolemy recorded as Baleocuros. These cross-references reinforce the strategic and cultural importance of Kolhapur during the early centuries of the Common Era.

Following the decline of the Satavahanas, the region likely came under the influence of the Kadamba dynasty in the 5th and 6th centuries CE. Although no inscriptions or coinage of the Kadambas have been recovered directly from Kolhapur yet, their proximity, especially their base at Halsi (modern-day Belgaum, Karnataka), and architectural similarities suggest a probable extension of their control into the district. Additionally, the spread of Kadamba influence is well documented in neighbouring regions like Goa, Karad (Satara district), and Belagavi, making their administrative reach into Kolhapur highly plausible.

Early Chalukya Consolidation and the Rise of Temple Architecture

The mid-6th century CE saw the rise of the Early Chalukyas, also known as the Chalukyas of Badami, who expanded northward into the Kolhapur region. Their rule, lasting until the 8th century, was marked by increased temple-building activity and deeper administrative reach into the western Deccan.

The Miraj Copper Plate Inscription (which were uncovered in the nearby Sangli district), though issued in the 10th century CE, records that Jatiga II, a vassal of the Chalukyas, held sway over the Kolhapur region. This inscription confirms that Kolhapur had been integrated into Chalukyan political structures. The Chalukyas are also associated with the earliest phase of the Mahalakshmi Mandir. Though extensively renovated in later centuries, the Mandir’s architectural style and its early granite form suggest that the original sanctum is believed by some to belong to this period.

Rashtrakuta Expansion and Samangad Fort

The decline of the Early Chalukyas in the mid-8th century paved the way for the rise of the Rashtrakutas, who established their capital at Manyakheta (present-day Malkhed, Kalaburagi district, Karnataka) under Dantidurga. His military campaigns quickly brought the western Deccan under his control, and Kolhapur district, owing to its location near key Sahyadri passes, would have held strategic importance.

Notably, their presence in the present-day district is well attested in a copperplate grant discovered at Samangad Fort near Gadhinglaj (Kolhapur district). Issued in the early years of Dantidurga’s reign (circa 753–754 CE), the inscription records his victories over the Chalukyas and several southern dynasties. The choice of Samangad as the site of issue suggests the fort was already a site of military and administrative relevance during the time.

Western Chalukyas and Campaigns in the Konkan

With the fall of the Rashtrakutas around the close of the 10th century, the Western Chalukyas of Kalyani emerged as the dominant power in the region. Kolhapur district once again became a contested zone in the power struggles between the Western Chalukyas and their rivals, notably the famous Cholas to the southeast.

The Miraj copperplate issued by Jayasimha II in Shaka 946 (1024–25 CE) provides evidence of renewed Chalukya military activity in the area. It records that a military encampment had been established near Kolhapur following a successful campaign against the Chola king Rajendra I. The same inscription refers to the conquest of the “Seven Konkans,” a term denoting the coastal belt west of the Sahyadri range, which may have included parts of Raigad and Sindhudurg as well.

The Shilaharas of Kolhapur

The fall of Rashtrakuta authority did not mark an end to Kolhapur’s political relevance. By the mid-10th century, the region passed into the hands of the Shilaharas, a branch of a larger family of feudatories who had earlier served under Rashtrakuta overlords. In time, one of their branches declared independence and established Kolhapur as their seat of power. The region is officially confirmed to have been their capital in Shaka 1109 ( 1187–88 CE), though evidence suggests it had served as their centre of rule well before that date.

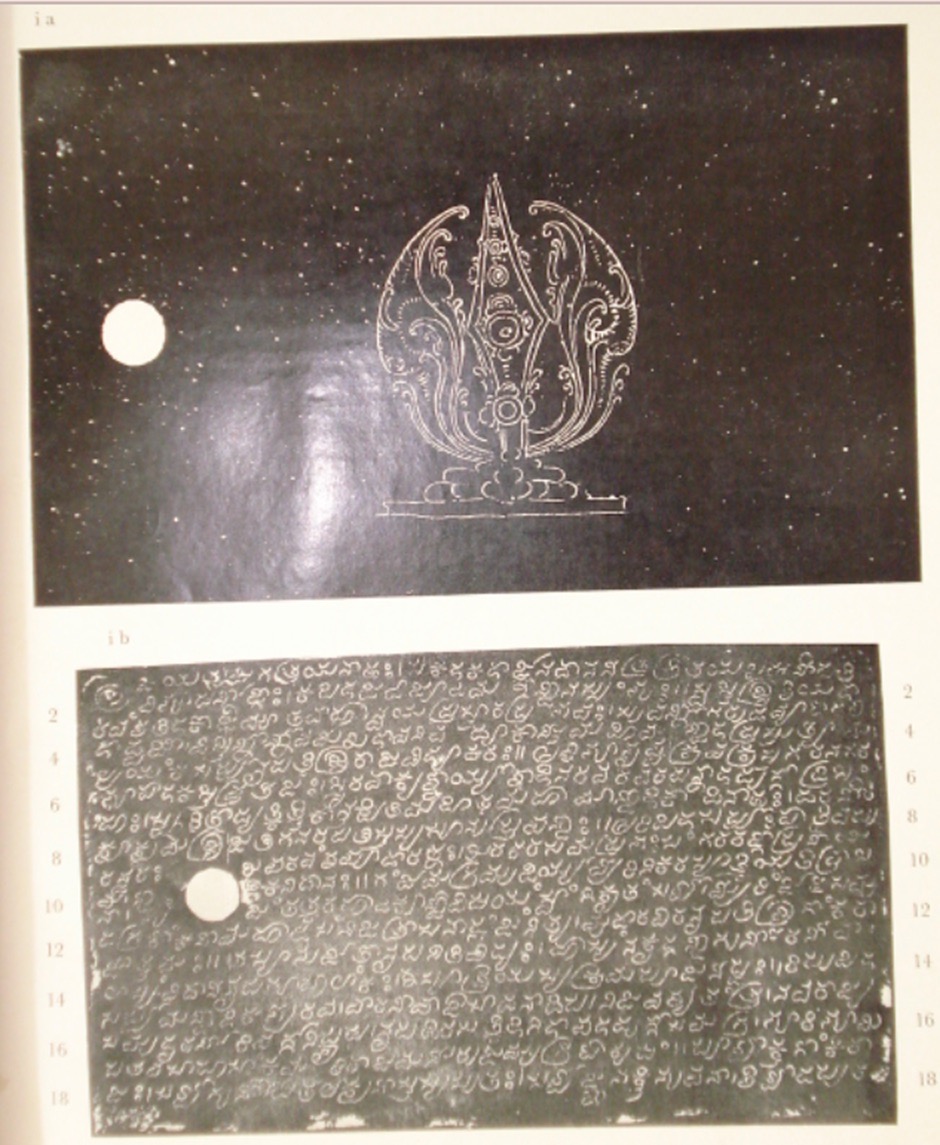

The Shilaharas of Kolhapur appear in numerous inscriptions found within the district and its environs, Miraj, Sedbal, and Khidrapur, among others, where their political control and religious affiliations are clearly attested. Though it is said that they were Jains by personal faith, they appeared to be syncretic in religious sympathies and honored the gram devi Mahalakshmi, whose Mandir they patronised, alongside the establishment of Jain institutions.

Prominent among the rulers was Gonka I, who is recorded to have founded a Jain Mandir in gratitude after being cured by a monk. His son, Marasinha, known in epigraphs by the epithet Pamaladurgadrisinha (the lion of Panhala Fort), continued the policy of fortification and territorial assertion, strengthening the family’s hold over key hill-forts in the region. Another ruler of considerable importance was Bhoja II, whose reign, marked by enduring political influence and architectural contributions, shall be discussed in greater detail below.

Noteworthy, too, is the tale of Chandala (also Chandrakala), daughter of Marasinha, whose celebrated beauty and learning became the subject of poetic admiration in distant Kashmir. Her swayamvara at Karhad attracted kings from far and wide, and her marriage to the Western Chalukya king Vikramaditya VI is said to have been commemorated in the writings of Kalhana and Bilhana, the latter penning the Vikramankadevacharita.

Gandaraditya I and the Consolidation of Shilahara Rule

During the closing decades of the 11th century, the Shilahara dynasty of Kolhapur attained a notable degree of consolidation under the reign of Gandaraditya I (c. 1080–1100 CE), a monarch whose authority appears to have been firmly established across the region. Gandaraditya’s reign was marked by temple patronage and literary references to Kolhapur as a religiously significant region. An inscription dated to 1126 CE, attributed to him, refers to Kolhapur as a Mahatirtha, a major pilgrimage site, underscoring the growing spiritual and regional importance of the city.

Though a follower of Jainism, Gandaraditya continued the policy of broad religious support. He granted endowments to Brahminical mandirs and ensured the protection of pilgrimage centres within his territory. His administration is associated with the further development of Kolhapur’s temple complexes and civic structures, which perhaps added to the district’s prominence in the western Deccan.

Bhoja II and the Construction of the Kopeshwar Mandir

One of the most architecturally significant developments under the later Silaharas occurred during the reign of Bhoja II (c. 1100–1175 CE). He is credited with overseeing the construction of the Kopeshwar Mandir at Khidrapur, a village located along the Krishna River near the Kolhapur–Sangli border.

The Kopeshwar Mandir, dedicated to Bhagwan Shiv, is noted for its remarkable stonework, intricate carvings, and unusual double sanctum layout. According to local tradition, the Mandir commemorates a moment of divine anger (kopa) associated with Shiva, hence the name “Kopeshwar.” The Mandir is architecturally unique in featuring both Shiva and Vishnu shrines within the same structure, an arrangement that reflects the broader religious synthesis of the region, which is believed to have been rare at the time.

Scholars believe that the Mandir’s construction was initiated during the Chalukya period and was later worked on under the commission of Bhoja II, who expanded the structure significantly. Inscriptions at the site refer to Bhoja II’s reign, temple grants, and donations to temple staff. The Kopeshwar Mandir remains one of the finest surviving examples of 12th-century Deccan temple architecture, and is a testament to the cultural patronage of the Kolhapur Shilaharas.

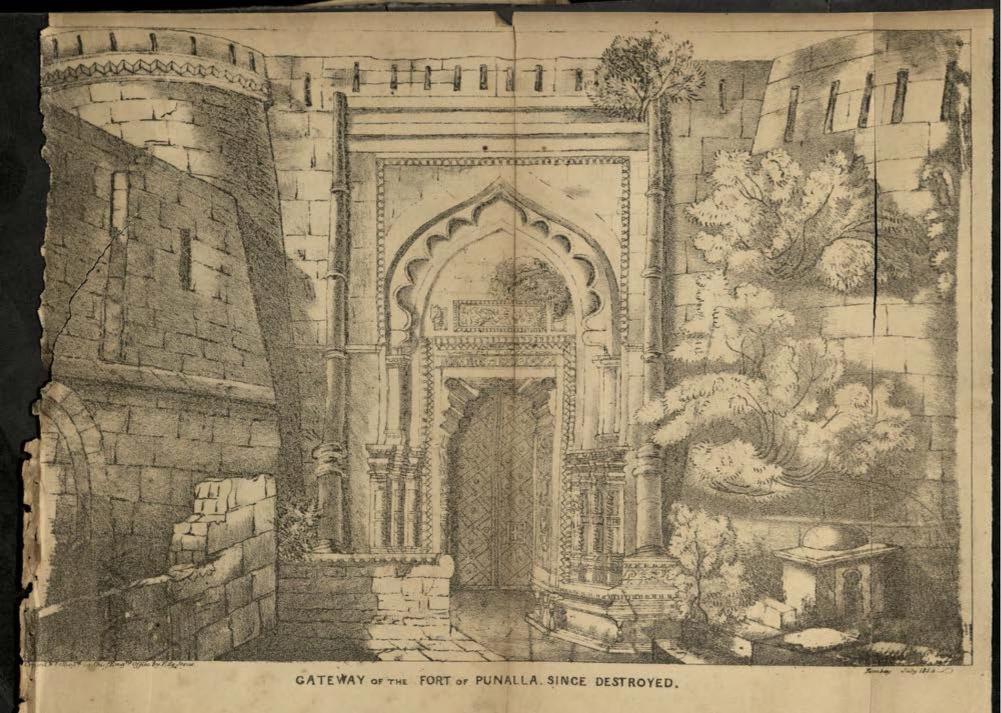

Construction of the Panhala Fort

Over the years of their rule, the military infrastructure of the Shilaharas in the district seems to have expanded in tandem with their religious and civic investments. One of the most significant constructions from this period is the Panhala Fort, located on the Sahyadri range northwest of Kolhapur. According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1886), the fort was built between 1178 and 1209 CE under Raja Bhoja II. Situated at a strategic altitude, Panhala controlled access between the Konkan coast and the Deccan plateau, and played a key role in protecting trade routes and asserting political control.

A copperplate inscription found at Satara notes that Bhoja II held court at Panhala between 1191 and 1192 CE, indicating its use as both a military outpost and administrative capital.

Panhala continued to be used and modified under subsequent rulers, including the Yadavas, Bahmanis, Adil Shahis, and the Marathas, but its initial layout and construction are credited to the later Silaharas, particularly during the reign of Bhoja II.

The Yadavas of Devagiri and the End of Silahara Rule

By the late 12th century, the Yadava dynasty of Devagiri (modern Daulatabad) began asserting dominance over western Maharashtra. The most notable ruler of this period was Simhana II (Singhana II, r. 1209–1247 CE), who expanded Yadava control across much of the Deccan, including Kolhapur district.

The transition from Shilahara to Yadava rule was not abrupt but occurred through a series of military campaigns. Notably, inscriptions from Khidrapur, located near the Kopeshwar Mandir, indicate that by 1213–1214 CE, the Kurundwad region (historically Mirinji) was under Yadava control. Other sources refer to Simhana as the king who defeated the last Shilahara ruler of Kolhapur and took possession of Panhala Fort, thus consolidating Yadava control over the district.

One poetic description compares Simhana to “an eagle who caused the serpent in the form of the mighty ruler Bhoj, hiding in the fort of Panhala, to take flight,” vividly illustrating the military contest for the region. The Yadavas, while expanding politically, also continued the practice of temple patronage and public works in Kolhapur, though their primary capital remained at Devagiri. Notably, it is said that the construction of the Kopeshwar Mandir (mentioned above) was completed during their time.

The Yadava rule in Kolhapur lasted until around 1306–1307 CE, after which the region fell under the influence of the Delhi Sultanate, beginning with the campaigns of Malik Kafur under Ala-ud-din Khilji.

Medieval Period

Bahmanis

Following the fall of the Yadavas, the Konkan region came under increasing attention from the Bahmani Sultanate, established in 1347 CE by Ala-ud-Din Hasan Bahman Shah. Though some traditions claim that Bahman Shah captured Kolhapur in their early years of rule, concrete evidence of effective Bahmani administration in the western Deccan is not found until much later.

In 1433 CE, Sultan Alauddin Ahmad Shah II sent Malik-ul-Tujar with a force against Shankar Rai of Khelna (Vishalgad Fort, Kolhapur district), a powerful local chief who controlled the surrounding hill forts. The expedition ended in failure. As the Bahmani troops retreated, they were ambushed in the rugged terrain of Khelna. More than 7,000 men were reportedly lost. In the aftermath, the forts of Khelna and Rangana (on the Kolhapur–Sindhudurg border) fell into the hands of Jakurai, Raja of Sangameshwar (Ratnagiri district).

In 1470 CE, Mahmud Gawan, vizier of the Bahmani Sultanate, launched a fresh campaign from a Kolhapur base. His aim was to clear the route to the coastal belt. Over the course of the campaign, it is noted that Bahmani forces fought in over fifty engagements. Rangana Fort was surrendered through negotiation. On 10 November 1470, Khelna also capitulated. These conquests enabled the Bahmanis to assert firmer control over parts of the Konkan interior during the final decades of their rule.

Adil Shahi Control and the Fortification of Panhala

After the disintegration of the Bahmani Sultanate in 1489 CE, its western dominions, including Kolhapur and the surrounding Ghats, passed into the hands of the newly established Adil Shahi dynasty of Bijapur. For nearly a century and a half, the Adil Shahis maintained a firm presence in the region through fortified posts and local garrisons.

The fort of Panhala (Kolhapur district), which had previously seen Bahmani control, was of particular strategic importance. It overlooked the main trade route connecting the Deccan plateau to the Konkan coast. During the reigns of Ibrahim Adil Shah I (r. 1534–1558 CE) and Ibrahim Adil Shah II (r. 1580–1627 CE), extensive repairs and fortifications were undertaken at Panhala. Persian inscriptions and structural remains attributed to this period, including military barracks and gateways, reflect the architectural imprint of the Bijapuri court.

Despite this consolidation, the region did not remain undisturbed. In 1636 CE, during a campaign led by the Mughal general Khan Zaman, Kolhapur was briefly captured. However, the Mughal hold proved short-lived. The territory soon reverted to Bijapur and remained under Adil Shahi control until the rise of the Marathas.

Marathas

The decline of the Adil Shahi kingdom was partly caused by the constant Mughal invasions from the north (the first one being in 1631) and partly by the rebellion of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj (1630-80 CE) of the Bhonsale dynasty (S/o of Shahji Bhonsale, an Adil Shahi Commander and Jijabai Bhonsale). Shivaji initiated his rebellion against the Adil Shah in 1646 when, at the age of 16, he captured the Torna Fort (currently in Pune). According to the Kolhapur district Gazetteer (1886), it was only in 1659 (after defeating Afzal Khan) that Shivaji took possession of Kolhapur and the fort of Panhala. Though soon after, in 1660, he lost control over the fort of Panhala and was only able to recapture it in 1673.

The Panhala Fort under the Marathas

Panhala Fort, located near Kolhapur city, is one of the most strategically significant forts in Maratha history. Panhala played a unique role in shaping political power struggles between different Maratha factions and against external forces like the Mughals and the British. The fort also overlooks the trade route between Maharashtra and Karnataka, making it a vital military base.

After the Yadavas, the fort changed hands between the Bahmani Sultanate and the Adil Shahi dynasty of Bijapur. Of all the rulers who controlled Panhala Fort, the Marathas had the most significant connection with it.

According to the district Gazetteer (1886), the fort came under Maratha control when Shivaji Maharaj captured it from the Adil Shahi forces in 1659, when he made a dash southwards after the defeat of Afzal Khan. Though soon after, in 1660, he lost control over the fort of Panhala and was only able to recapture it in 1673. Finally, in 1675, Shivaji (now being crowned as the independent ruler of the Maratha Swaraj) captured Kolhapur during his Southern campaign (1674-77 CE).

The Famous escape of Shivaji from Panhala, 1660

The story behind capturing the Panhala Fort is very famous. In 1660, the Bijapur army attacked to reclaim the fort, forcing Shivaji to make his famous escape to Vishalgad. When Siddi Johar (a general of the Adil Shahi Sultanate) laid siege to Panhala, Shivaji Maharaj and his forces held out for five months but eventually had to escape due to food shortages. Using a clever deception strategy, Shivaji escaped to Vishalgad, while his commander Baji Prabhu Deshpande made a heroic last stand at Pavan Khind. This escape is considered to be one of the most legendary events in Maratha history.

Shivaji later reconquered Kolhapur in 1675 CE, strengthening Maratha control over the region. Panhala became a crucial fort in the Maratha military network, securing the Deccan routes.

Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj

Towards the end of his reign, Shivaji used Panhala Fort to confine his eldest son, Sambhaji. It was at Panhala that Sambhaji received news of his father's death in 1680. Upon hearing of Shivaji's passing, Sambhaji freed himself and sought to assert control over the affairs of the state from Panhala. However, he soon faced resistance from rival factions at Raigad, who had declared Rajaram, Shivaji's younger son, as his successor. After a brief power struggle, Sambhaji was able to gain control of the Maratha state (with the help of commanders such as Hambirao Mohite) and was made the second Chhatrapati.

After his capture and subsequent death in 1689, the fort of Panhala fell into the hands of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb. However, it was recaptured in 1692 by the Maratha commander Parshuram Trimbak. The Mughals laid siege to the fort once again, but in 1693, the siege was lifted following a coordinated assault by three Maratha forces led by Ramchandra Pant, Shankaraji Pandit, and Dhanaji Jadhav. Despite this setback, the Mughals continued their efforts against the fort sporadically until 1696.

Following the death of Chhatrapati Rajaram in 1700, Panhala was eventually surrendered to Aurangzeb in 1701. During this period, Aurangzeb established a temporary encampment near Panhala, with the assistance of Sir William Norris, an ambassador of the East India Company, after also capturing Vishalgad. However, within a few months, the fort was once again retaken by the Marathas under the leadership of Ramchandra Pant.

Later on, Rajaram’s widow, Maharani Tarabai, used Panhala as a stronghold to continue the fight against the Mughals and later against Shahu Maharaj, her nephew. Panhala became the political base of the Kolhapur Bhonsale dynasty after the Maratha Empire split into Satara and Kolhapur factions in 1714.

Maharani Tarabai

Maharani Tarabai played a pivotal role in shaping the political and military landscape of Kolhapur during the early 18th century. The daughter of Hambirao Mohite, a renowned military commander and the fifth Sarsenapati (Commander-in-Chief) of the Maratha Empire, Tarabai was married to Rajaram, the younger son of Chhatrapati Shivaji and his wife Soyrabai.

Following the execution of Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj in 1689, and the capture of his wife, Yesubai, and son Shahu by the Mughals, leadership of the Maratha kingdom passed to Rajaram. He was informally crowned Chhatrapati, serving as a regent on behalf of his nephew, the imprisoned Shahu.

With mounting Mughal pressure, Rajaram was forced to flee from Panhala to the Jinjee fort in present-day Tamil Nadu, where he continued to lead resistance efforts with the help of Tarabai until the fort fell to the Mughals in 1698. He then returned to Satara and resumed military operations, but died in 1700 due to lung complications.

In the aftermath of his death, Tarabai declared her son, Shivaji II (later known as Shivaji I of Kolhapur), as the next Chhatrapati, assuming the regency herself, as he was only four years old. During her regency, Tarabai demonstrated remarkable leadership and military acumen, successfully defending Maratha territories and preventing further Mughal encroachment into the remaining strongholds of the Maratha state.

Formation of the Kolhapur Kingdom

After the death of Aurangzeb in March 1707, Prince Azam Shah released Shahu from Mughal captivity. Shahu returned to Maharashtra, where many Maratha chiefs rallied behind him as the rightful heir to the Maratha throne. In October 1707, he faced Rani Tarabai’s forces at the Battle of Khed (in present-day Pune). Tarabai was decisively defeated, largely due to the last-minute defection of the influential Maratha commander, Dhanaji Jadhav. Shortly after, she also lost control of the strategic fort of Satara.

Shahu established Satara as the new capital of the Maratha kingdom and was formally crowned Chhatrapati in January 1708. By 1710, the political division of the Maratha state into two principalities—Satara under Shahu and Kolhapur under Tarabai- had become a reality.

However, Tarabai and her son Shivaji II were soon overthrown by Rajasbai, another widow of Rajaram, who in 1714 installed her son, Sambhaji II (styled as Sambhaji I of Kolhapur), as the ruler of Kolhapur.

For a brief period, Sambhaji I entered into a secret alliance with the Nizam of Hyderabad in an attempt to challenge Shahu's supremacy. This alliance collapsed after the Nizam’s defeat by Peshwa Bajirao I in the Battle of Palkhed (1728), which forced him to sign the Treaty of Mungi-Shevgaon and withdraw his support for Sambhaji I. It is also believed that Tarabai had decided to live in Satara itself. The rivalry between the Satara and Kolhapur branches was formally resolved in 1731 with the signing of the Treaty of Warna. Through this agreement, both parties recognized each other’s authority. Shahu ceded territory between the Krishna and Tungabhadra rivers to Sambhaji I. At the same time, Kolhapur accepted a vassal relationship under the suzerainty of Shahu.

According to Stewart Gordon in the New Cambridge History of India, The Marathas (1600-1818), “ [for both the parties] this division was largely successful; Kolhapur survived as a separate, rarely threatening state throughout the 18th century (and as a princely state in the 19th and 20th century).”

Sambhaji II and Jijabai

Chhatrapati Shahu ruled Satara until 1749. He had two adopted sons, Ranoji Lokhande, renamed Fatehsinh I, and Rajaram II of Satara (1726–1777), who succeeded him as Ramaraja Chhatrapati. Rajaram II had been brought to Shahu by Tarabai, who initially claimed he was her grandson through Shivaji I of Kolhapur and thus a direct descendant of Shivaji Maharaj. When he refused to serve her political ambitions, she denounced him as an imposter, only to later acknowledge his legitimacy before the Maratha sardars.

In Kolhapur, Sambhaji I died without an heir in 1760. His widow, Jijabai, adopted the son of Shahaji Bhonsle of Kanvat, a collateral descendant of Shivaji’s line, naming him Shivaji II (1756–1813). The Peshwa, who wished to unite the Satara and Kolhapur branches under his authority, initially opposed the adoption but eventually accepted it, following custom and public sentiment. During Shivaji II’s minority, Jijabai governed Kolhapur, successfully preventing the Peshwa from seizing large portions of the state.

Kolhapur as a Princely State

After Jijabai’s death, Kolhapur faced attacks from regional powers allied to the Peshwa, including Patwardhan Kannherrao Trimbak of Sangli and the Pant Pratinidhi of Aundh. The following year, local chiefs from Kagal, Bavda, and Vishalgad resisted Peshwa Madhavrao’s forces. One Kolhapur sardar, Yeshwantrao Shinde, even sought Hyder Ali of Mysore’s aid, achieving partial success.

After Yeshwantrao Shinde died in 1782, Shivaji II found himself in a precarious situation. The state was engaged in constant conflicts with the likes of the Sawants of Sawantwadi, Nipanikar, the chief of Nipani, the Gadkaris in Bavda (In each fort in the Maratha country, a permanent garrison was kept up composed of men called Gadkaris, for whose maintenance lands were assigned, which they held on condition of service). The Peshwa added to the troubles by funding the hostilities committed against the state of Kolhapur by their neighbouring smaller states. The British too raided the coastline quite a few times which led to Shivaji II to sign a treaty with them on the 1st of October 1812, he ceded to the British the harbour of Malvan and its dependencies, engaged to abstain from sea raids and wrecking, renounced his claim to the districts of Chikodi and Manoli, and further agreed not to attack any foreign State without the consent of the British Government, to whom all disputes were to be referred In return for these concessions the British renounced all their claims against the Raja, who received the British guarantee for all the territories remaining in his possession "against the aggression of all foreign powers and States." Kolhapur, in short, became a protected State under the British Government.

Colonial Period

By the early 19th century, the region of Kolhapur, located in present-day southwestern Maharashtra, was a Maratha princely state ruled by a branch of the Bhonsle dynasty. Its political fortunes shifted significantly during the gradual expansion of British influence across the Deccan. On 1 October 1812, a treaty was signed between the Raja of Kolhapur and the East India Company, placing Kolhapur under British protection. This marked a formal entry into indirect British rule.

Under this treaty, the Raja relinquished control over Chikodi and Manoli (present-day Karnataka, adjoining Hatkanangle taluka of Kolhapur district), and ceded Malvan (a coastal town now in Sindhudurg district) to the British. In addition, the Raja agreed not to engage in hostilities or form alliances with any external power without prior British approval. While the Bhonsle rulers retained titular authority, the treaty curtailed Kolhapur’s sovereignty in foreign affairs.

At this stage, Kolhapur retained internal autonomy, and administrative functions remained largely in the hands of the local royal court. However, British political officers began to play a more prominent advisory role, setting the stage for deeper involvement in subsequent decades.

Kolhapur’s Status Following the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1818)

The defeat of the Peshwa in the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1818) marked a decisive shift in western India's political order. The British dismantled the Peshwa’s authority and assumed direct control over large portions of Maharashtra and Karnataka. While many Maratha territories were annexed, Kolhapur was allowed to continue as a princely state under British suzerainty.

During this period, Shambhu alias Abhasaheb, son of Shivaji III, ascended the throne. Contemporary records describe him as peace-inclined and cooperative with the British. In return for his support during their campaign against the Peshwas, the British restored to him administrative control over Chikodi and Manoli and allowed him oversight of portions of the Konkan coast, particularly areas corresponding to present-day Kankavli and Malvan talukas.

However, Shambhu’s rule was short-lived. In 1821, he was assassinated by a sardar from Karad (now in Satara district), reportedly angered by the grant of village lands to a royal servant. This incident reflects the persistent internal tensions between traditional zamindar elites and emerging royal administrative preferences, often shaped by British expectations of order and loyalty.

Administrative Decline under Shahaji (Babasaheb), 1821–1838

Following Shambhu’s death, the regency governed briefly in the name of his infant son. Upon the child’s death, Shahaji (Babasaheb), another son of Shivaji III, was installed as ruler. His tenure is widely recorded as one of instability and misrule.

According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1886), Shahaji’s administration was marked by insecurity and financial mismanagement. At one point, he reportedly looted his own treasury to seize state jewels, which he sought to sell to sustain personal extravagance. There are also documented instances of armed raids on towns under British jurisdiction, violating the conditions of the 1812 treaty.

In response to these transgressions, a new treaty was signed in 1826, restricting Shahaji from attacking the neighbouring jagir of Kagal and the territory of Ichalkaranji (both now talukas in Kolhapur district). A subsequent agreement in 1827 limited the state’s standing military to 400 cavalry and 800 infantry, effectively curtailing its martial capabilities. A final treaty in 1829 addressed growing civic disorder, formally bringing aspects of internal security under British oversight.

The Kittur rebellion of 1824 (in present-day Belagavi district, Karnataka) had earlier heightened British concerns over regional uprisings. After the rebellion, in which several British officers were killed, any increase in military activity by princely states, including Kolhapur, was viewed with suspicion. In 1826, the British dispatched troops to Kolhapur to enforce compliance with treaty terms. Shahaji was compelled to disband large parts of his army and affirm British political authority in the region.

Shahaji died of cholera in 1838. His reign marked the transition of Kolhapur from a semi-autonomous Maratha state to a subordinate unit of the British imperial structure. While the title of Chhatrapati was preserved, substantive governance was increasingly directed by British political superintendents stationed at Kolhapur.

The Gadkari Uprising in Kolhapur

After the death of Chhatrapati Shahaji (Babasaheb) in 1838, Kolhapur State entered a period of regency. Real control remained with the royal household and a small group of administrators based in Kolhapur city. Shahaji’s elder son, Babasaheb (not to be confused with his father), was nominally in power, but governance was largely exercised by his aunt, the Divansaheb.

This era was marked by administrative unrest and rising tensions among different castes and political groups. The Bombay Presidency Gazetteer (1886) records that there was widespread discontent among both the landed elites and military retainers, particularly the Gadkari community, who traditionally served as fort commanders and local militia, many under the Marathas. To address corruption and inefficiency in state administration, the British installed Daji Krishna Pandit, a Brahmin official known for his organizational capabilities, as part of the political establishment in Kolhapur.

Pandit had previously aligned with British interests and was instrumental in implementing reforms intended to centralize authority and reduce the influence of older Maratha and military factions. However, his appointment and subsequent policies generated hostility among the local Maratha leadership and sections of the court.

This tension culminated in the Gadkari Revolt of 1844, centred in and around Panhala Fort (located in present-day Panhala taluka, Kolhapur district). The Gadkaris, supported by various Maratha factions, captured Daji Krishna Pandit and temporarily took control of strategic positions. British forces responded swiftly, and Pandit was rescued. A confrontation followed in which the rebels were decisively defeated by British troops stationed in the Deccan.

To re-establish order, the British appointed Captain D.C. Graham as Political Superintendent of Kolhapur. His mandate included reorganising the administration and stabilising revenue systems. Graham was also tasked with addressing the state’s financial liabilities, many of which had been incurred during the suppression of the revolt and earlier periods of unrest. The presence of British officers became more formalised during this time, with increasing control over judicial, fiscal, and military functions.

Ramji Shirsat’s Revolt and Local Dissent in Kolhapur (1857)

Despite administrative reorganisation after the Gadkari revolt, tensions persisted between the state’s military ranks and the emerging bureaucracy. Discontent was especially visible among sections of the sepoy regiments stationed in and around Kolhapur city.

In such a time, when widespread uprisings erupted across north and central India in 1857, Kolhapur saw its own, though limited, episode of unrest. The broader movement, commonly referred to as the First War of Independence, involved sepoy regiments, disinherited rulers, and disgruntled landholders challenging the expansion of British authority. Within Kolhapur, dissatisfaction among certain sepoy units found expression in a locally led revolt.

On the night of 31 July 1857, a group of around 200 armed men, led by Ramji Shirsat, a sepoy of local origin, launched an attack on the regimental treasury and European officers’ quarters near the present-day Kasaba Bawada area of Kolhapur. The men, drawn mainly from Pardesi and Maratha ranks, seized weapons and supplies before beginning their march southwards toward Ratnagiri, intending to join rebel forces active along the coast.

The response from the state was immediate. The Kolhapur court, which had grown increasingly dependent on external advisors since the 1840s, acted quickly to restore order. Loyal troops, assisted by forces from outside the state, intercepted the rebels before they could exit Kolhapur territory.

Ramji Shirsat and twenty-five of his associates were captured and executed near the southern edge of the city. Though the events were recorded in official correspondence, no formal memorials were established at the time. The suppression of the revolt also led to political fallout within the royal family: Chimasaheb, brother of the Chhatrapati, was accused of sympathising with the rebels and was exiled to Karachi.

In recognition of the court’s loyalty and assistance in containing the rebellion, the ruling Chhatrapati, Babasaheb, was rewarded by the colonial administration with the honorary title ‘Star of India’, and state debts owed to the British were waived.

The Death of Shivaji VI and Political Unrest in Kolhapur (1866–1883)

Following the death of Chhatrapati Babasaheb in 1866, the Kolhapur throne passed to his adopted son, Shrimant Narayanrao Dinkarrao Bhosale, renamed Shivaji VI upon accession. He was adopted from the Bhosale family of Satara, part of the extended Maratha royal lineage, and installed as the heir under British approval. As Shivaji VI was still a child at the time, state affairs were placed under a Regency Council, composed of the Chief of Kagal, the Divan, the Chief Judge, and the Chief Revenue Officer.

As he grew older, however, concerns were raised by the British administration regarding Shivaji VI’s mental health. By the early 1880s, he had been removed from public life, and the Kolhapur administration continued under regency, with formal power remaining with the British-backed council. In 1883, Shivaji VI died under confinement at Ahmednagar (present-day Ahilyanagar district, Maharashtra), where he had been sent for treatment.

His sudden and unexplained death attracted widespread suspicion across Kolhapur district and beyond. Among the local population, there were circulating rumours that the young ruler had been mistreated or even subjected to physical abuse during his confinement. Notably, these allegations gained traction in the regional press, most notably through the efforts of Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Gopalrao Agarkar, editors of the Marathi newspapers Kesari and Mahratta. Both publicly questioned the circumstances of the Raja’s death, accusing his European guardians of negligence or violence.

The accusations led to legal proceedings. Tilak and Agarkar were unable to provide evidence that would hold in colonial courts, and both were sentenced to five months’ imprisonment for contempt. Despite the legal outcome, the episode significantly shaped public opinion in western Maharashtra. The case became a focal point in the emerging discourse on colonial repression, princely autonomy, and the rights of adopted heirs under indirect rule.

In Kolhapur itself, the controversy deepened political divides. While the Regency Council continued to administer the state, public confidence in the neutrality of British oversight had diminished. Among educated urban groups in Kolhapur, Ichalkaranji, and Panhala, the Shivaji VI case was remembered as a moment of humiliation and external interference.

Social Reform and State Development under Chhatrapati Shahu IV (Rajarshi Shahu Maharaj) of Kolhapur (1894–1922)

Chhatrapati Shahu IV ascended the Kolhapur gadi in 1894 after the regency that followed Shivaji VI’s death. His reign, in many ways, marked a clear break from precedent. Unlike earlier rulers, Shahu used the authority of the princely state to carry out direct social reform, most notably in the areas of caste, education, and rural development.

He introduced free and compulsory education across the state, starting in Kolhapur city and extending to towns such as Ichalkaranji, Kagal, and Radhanagari. For the first time, students from backward castes, Muslim, Christian, and Jain communities were given access to state-funded hostels and scholarships. In a landmark policy, Shahu implemented 50% reservation in schools and state employment for underrepresented communities.

To break the monopoly of Brahmins over Vedic learning and ritual practice, Shahu opened Vedic schools to non-Brahmin students and dismissed priests who refused to perform rituals for lower castes. He established the Deccan Rayat Association to bring non-Brahmin voices into politics and administration.

Agriculture was further supported through the establishment of the Edward Agricultural Institute, which offered training in cropping patterns and water management. To ensure long-term irrigation supply, he commissioned the construction of the Radhanagari Dam, which served both agricultural and drinking water needs across the southern parts of the district.

Shahu Maharaj also supported initiatives in women’s education and social welfare. He legalised widow remarriage, opposed the Devadasi system, and banned child marriage through state-level proclamations. Girls’ schools were opened in Kolhapur city and satellite towns, some in collaboration with missionaries and reformist societies.

In the cultural domain, Shahu encouraged the growth of Kolhapur’s music gharanas, wrestling akhadas, and state-sponsored theatre troupes. He was a regular patron of traditional performing arts and court-sponsored musicians, while also inviting modern educational reformers and press editors into his administrative fold.

Shahu IV ruled until 1922, and his reign is widely regarded as a foundational period in Kolhapur’s transition from a feudal princely estate to a socially responsive, semi-modernised princely state. His reforms left a lasting impact not only in Kolhapur but across western Maharashtra, influencing the development of anti-caste politics, rural education, and state-led welfare models in the decades to come.

Rajaram III and the Final Phase of Princely Rule in Kolhapur (1922–1949)

Following the death of Chhatrapati Shahu IV in 1922, the gadi of Kolhapur passed to his biological son, Chhatrapati Rajaram III. Though his rule lacked the scale of reform associated with his father, Rajaram continued several key initiatives in education, public health, and minority welfare.

He expanded free primary education and encouraged female literacy, particularly in Kolhapur city, Ichalkaranji, and Ajara. State-supported schools for girls and higher secondary institutions received increased funding during his reign. Rajaram III also carried forward his father’s work in public health, overseeing the establishment of sanitation schemes, vaccination centres, and rural dispensaries.

His administration maintained a policy of caste inclusion, ensuring continued representation of non-Brahmin communities in local governing bodies and advisory councils. However, the political context was shifting. Nationalist sentiment was rising, and princely states across India faced increasing pressure to democratise.

Rajaram III died in 1940. He was succeeded by Chhatrapati Shivaji VII, a child ruler who died in 1946 at the age of four. During this period, Kolhapur State was governed by a council of regents. With no surviving direct heir, the court selected Vikramsinhrao Patankar, a grandson of Shahu IV, from the Puar dynasty of Dewas, to ascend the throne. He ruled as Chhatrapati Shahaji II.

Shahaji II remained the titular head of Kolhapur until the state acceded to the Indian Union in 1949. The merger marked the end of princely governance in the region. After integration, Kolhapur became part of Bombay State, and later, with the formation of Maharashtra in 1960, a district within the new state.

Local Print Culture and the Role of Pudhari

Many developments took place during the closing years of the colonial period. The growth of print culture in Kolhapur district began in the early 20th century, shaped by the expansion of vernacular education, local reform movements, and the rise of political consciousness in the princely state. By the 1930s, the region had developed a small but active reading public, concentrated in Kolhapur city, Ichalkaranji, and Gadhinglaj, and supported by libraries, reading rooms, and social reform societies.

In this environment, Pudhari was established as a weekly Marathi newspaper in 1937, based in Kolhapur city. Founded by Ganpatrao Jadhav, the paper focused on regional issues, princely politics, and social reform. It gained popularity for its coverage of local grievances, particularly in rural areas and among non-elite communities.

By 1939, Pudhari had transitioned into a daily newspaper. Its growth paralleled the wider political shifts taking place in Kolhapur, especially the rise of non-Brahmin leadership, the questioning of hereditary authority, and increasing demands for social and economic justice. The newspaper covered both local administration and national politics, linking village-level concerns in Hatkanangle, Shahuwadi, and Kagal with larger debates around representation, education, and land reform.

Cultural Production and the Legacy of Mahadev Vishwanath Dhurandhar in Kolhapur

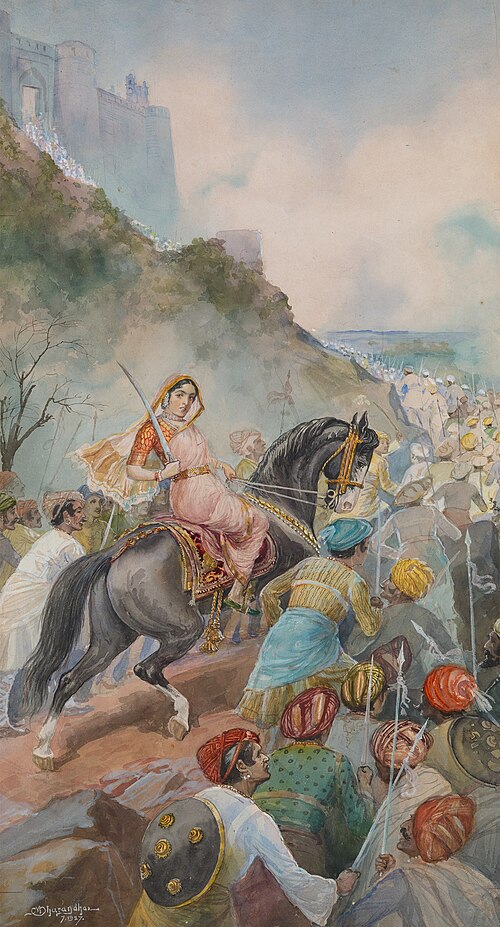

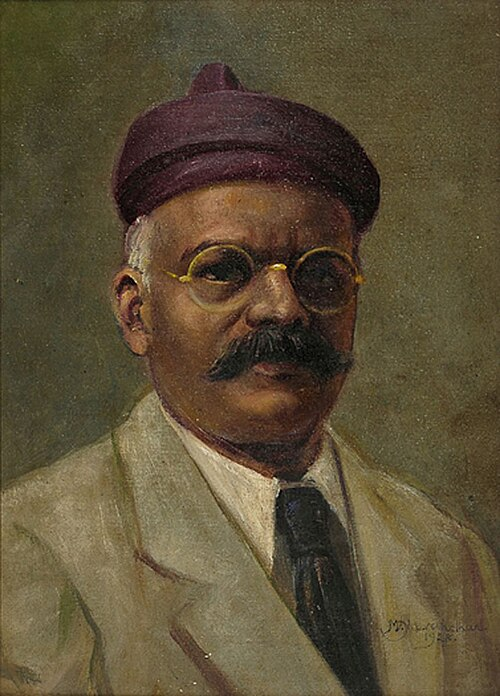

There were many individuals, too, during this time whose work left a lasting impact on Kolhapur’s cultural and visual history. Among the most prominent was Mahadev Vishwanath Dhurandhar (1867–1944), a painter and illustrator known for his detailed portrayals of Indian social life, epic themes, and colonial-era public scenes.

Born in Kolhapur, Dhurandhar showed artistic talent early in life. Encouraged by his father, he began training under Abalal Rahiman, a respected court painter in Kolhapur. In 1890, he enrolled at the Sir J.J. School of Art in Bombay, where he studied under John Griffiths, then principal of the school. Dhurandhar graduated in 1895 and went on to join the faculty.

Between 1896 and the 1930s, Dhurandhar produced a wide range of work, including illustrations for postcards, school textbooks, and colonial publications. His paintings often depicted scenes from Hindu epics, urban life in Bombay, and historical figures such as Shivaji Maharaj and Maharani Tarabai. Several of his works were commissioned by princely courts, including Kolhapur, Aundh, and Baroda.

One of his major commissions came from Maharaja Bhawanrao Pantpratinidhi of Aundh in 1926, who tasked him with painting episodes from the life of Shivaji. Dhurandhar’s works were exhibited in both India and Europe, with some displayed at institutions such as South Kensington Museum (London) and Buckingham Palace.

Though he spent most of his professional life in Mumbai, Dhurandhar maintained close ties with Kolhapur’s artistic circles. His visual depictions of Maharani Tarabai, Maratha court scenes, and local customs helped shape the public memory of Kolhapur’s early modern history.

Dhurandhar served as Headmaster and later Vice-Principal of the Sir J.J. School of Art, retiring in the 1930s. In 1938, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, London.

His legacy in Kolhapur lies not only in the historical subjects he portrayed but also in the role his art played in visually documenting the political symbols, gender roles, and social life of the region during a period of rapid transformation.

Post Independence

After the merger of Kolhapur State into the Indian Union in 1949, the region became part of Bombay State. With the States Reorganization Act of 1960, Kolhapur was incorporated into the newly formed state of Maharashtra. The administrative boundaries of the former princely state largely correspond to those of the present-day Kolhapur district.

Kolhapur participated in India’s first general elections in 1952, transitioning from royal governance to elected representative rule. The princely court was formally dissolved, though members of the royal family continued to hold social and cultural influence in the district.

Founding of Shivaji University

In the early post-independence period, access to higher education remained limited across southern Maharashtra. Colleges affiliated to the University of Mumbai or University of Pune (now known as Savitribai Phule Pune University) were often distant, urban-centred, and inaccessible to rural and first-generation learners from districts such as Kolhapur, Sangli, Satara, and Solapur. Students from agrarian and working-class backgrounds, especially, faced both economic and social barriers to enrolment.

To address this gap, the Government of Maharashtra established Shivaji University in Kolhapur city on 18 November 1962. The university was named after Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, in recognition of the region's historical identity and the legacy of princely governance centred in Kolhapur.

The foundation of the university was made possible through sustained pressure from local leaders, educational reformers, and social organisations. Yashwantrao Chavan, then Maharashtra’s Chief Minister and a native of the region, played a central role in securing political support and funding. The university’s jurisdiction was designed to cover the entire southern belt of Maharashtra, with a specific mandate to expand access for rural, backward-caste, and economically disadvantaged students. The university was, notably, inaugurated by Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, the then President of India.

Sources

Amina Hasan, Barkha Bhalla, Upma Chaturvedi. 2019. “Revolt of 1857 in India: A Geographical Perspective.” Vol. 9 Issue 2, International Journal of Research in Social Sciences.https://www.ijmra.us/project%20doc/2019/IJRS…

Avanish R. Patil. 2008. “Representation of Imperial Authority in Kolhapur: A Political Interpretation of the Selection, Accession and Installation of Shahu”. Vol 41, No 1, Journal of Shivaji University (Humanities and Social Sciences).

James M Campbell, 1886. Gazetteer Of The Bombay Presidency, Vol 24. Kolhapur. Govt Central Press, Bombay.

Kolhapur District Gazetteer. 1960. Revised Edition. Directorate of Government Printing, Bombay.

Manohar Malgonkar. 1960. Chhatrapatis Of Kolhapur. Popular Prakashan, Bombay.

Nikhil Inamdar. 2017. Kopeshwar: Unearthing Maharashtra’s Khajuraho. Peepul Tree Stories.https://www.livehistoryindia.com/story/monum…

Stewart Gordon. 1993. New Cambridge History of India, The Marathas (1600-1818). Cambridge University Press.

Times of India. 2017. Kopeshwar Temple: A Hidden 12th Century Relic. Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kol…

V.V. Mirashi. 1977. Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum. Vol.VI: Inscriptions of the Silaharas. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

Vaibhav Fadtare. 2021. History of Kopeshwar Temple Khidrapur. YouTube.https://youtu.be/u-4H0lRGrvs?si=jFxudJTH_fAc…

Wikipedia, Kolhapur District. Wikipediahttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kolhapur_distr…

Last updated on 17 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.