Contents

- Architecture of Prominent Sites

- Kanheri Caves

- Jogeshwari Caves

- St. John the Baptist Church

- Castella de Aguada

- Basilica of Our Lady of the Mount

- The Capital, Bandra Kurla Complex

- Residential Architecture

- The Late 19th - Mid 20th Century Homes of the District

- A Residential Space at Mahatma Gandhi Road, near Mulund Station (W)

- A Residential Space near Mulund Station (W)

- Igloo Houses for Cement Factory Workers in Mulund

- Block Houses of Mulund Colony

- Homes of the 1980s: Apartment Spaces

- Girikunj

- Residences of the 21st Century

- Golden Willows, Vasant Gardens

- Sources

MUMBAI SUBURBAN

Architecture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Architecture is often seen through the lens of monuments and grand structures, yet everyday buildings reveal just as much about the cultural and historical forces that have shaped a place. In Mumbai, domestic and public spaces alike carry the marks of changing rulers, shifting economies, and evolving ways of life. From early settlements to modern expansion, each phase in the city’s history has left an imprint on how spaces are built, used, and remembered. The architectural landscape has been shaped by cultural, social, and political dynamics. Mumbai’s architecture—both old and new—offers insight into the broader transformations that have defined the region over centuries. Through its buildings, one can trace the story of the district’s identity, resilience, and adaptation over time.

Architecture of Prominent Sites

The architecture of public spaces in Mumbai Suburban reflects a temporal journey from ancient religious sites to modern commercial developments. The Jogeshwari and Kanheri Caves represent early rock-cut traditions that marked the religious landscape of the region for centuries. By the 16th and 17th centuries, Portuguese influence shaped the built environment through churches and coastal fortifications. The early 20th century introduced Gothic Revival forms, while the present-day skyline is defined by high-rise commercial architecture and sustainable design. Together, these shifts illustrate the suburb’s transformation into a dynamic financial and economic hub.

Kanheri Caves

The Kanheri Caves are a group of over 100 rock-cut Buddhist monuments located within Sanjay Gandhi National Park in Borivali, Mumbai. Carved into basalt between the 1st century BCE and the 10th century CE, the site served as a major Buddhist monastic center for nearly twelve centuries. These caves are among the most significant early examples of rock-cut architecture in Western India and provide a detailed record of the development of Buddhist architecture, art, and monastic life.

Excavated from basalt rock typical of the Deccan plateau, the Kanheri Caves include monastic cells (viharas), prayer halls (chaityas), cisterns, stupas, and benches. Cave No. 3, the most prominent chaitya hall, features a vaulted roof over the nave and a flat-roofed aisle, with two preserved stambhas (freestanding pillars) at the entrance resembling those at Karla Caves. Many of the early excavations are simple and austere, while later ones display elaborate carvings, sculptures of the Buddha in various forms, and architectural ornamentation.

![The vaulted roof over the nave and preserved stambhas in Cave No. 3 reflect early chaitya hall architecture at Kanheri.[1]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai-suburban/architecture/the-vaulted-roof-over-the-nave-a_YYCZHIf.png)

Architectural elements at Kanheri demonstrate a steady evolution. The replacement of wooden elements, such as the screen in front of the chaitya, with stone was a key advancement. Later caves feature verandas, sculpted screens, and improvements in ventilation and lighting, such as the introduction of open windows at head level in some caves. Grated windows, with carved square depressions and circular holes, are also found in several caves, though some exhibit crude workmanship.

Pillars at Kanheri often include sculpted yakshas with raised arms on all sides. The forms of excavations—primarily square and rectangular—reflect the functional and symbolic logic of early Buddhist planning.

Jogeshwari Caves

The Jogeshwari Caves are a group of rock-cut caves located in the Jogeshwari suburb of Mumbai. Believed to date back to the 6th century CE, these caves are among the earliest examples of Hindu cave architecture in the Deccan and hold significant value in understanding the transition from Buddhist to Brahmanical religious patronage in Western India. Excavated into basalt rock, the site is considered an early Shaiva monument and is frequently cited in scholarship on pre-medieval Brahmanical cave architecture. Historian Walter Spink has described the Jogeshwari Caves as the "grandfather of all" Hindu cave temples, noting their early date and their importance in shaping later rock-cut forms in the Deccan region.

These caves are attributed to the Kalachuri dynasty (c. 550–620 CE), which succeeded the Traitukas and were known patrons of the Pashupata Shaivite tradition. Under their rule, several Shaiva cave temples were excavated across the region, with Jogeshwari representing one of the earliest and most extensive examples.

The scale and complexity of the Jogeshwari Caves make them a critical site in tracing the early development of Hindu rock-cut architecture, particularly under the influence of Shaivism during the early medieval period. The architectural layout of the Jogeshwari Caves consists of a large central hall, cut directly into the rock, supported by 20 intricately carved pillars. At the heart of the complex lies a square sanctum enshrining a Shivling, symbolizing its devotional function. The cave includes a number of subsidiary rock-cut spaces and sculptural panels, with certain elements—such as the portrait sculptures and hall design—reflecting stylistic influences of Mahayana Buddhist cave traditions, which preceded the site.

![Square sanctum with Shivling at the heart of Jogeshwari Caves, reflecting early Hindu rock-cut architecture.[2]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai-suburban/architecture/square-sanctum-with-shivling-at-_fdz5qSh.png)

![Central hall supported by 20 carved pillars, showcasing the structural planning of Jogeshwari Caves.[3]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai-suburban/architecture/central-hall-supported-by-20-car_npLUGMN.png)

St. John the Baptist Church

The St. John the Baptist Church in Andheri follows the Portuguese Colonial architectural style. Built in 1579 during the Portuguese rule over Salsette Island, the church is located in the SEEPZ Industrial Area in Andheri. It was part of a larger network of religious structures established between 1534 and 1737, when the Portuguese developed coastal settlements and Christian communities across the region. Once active, the church fell into disuse after an epidemic struck the area.

The site now lies in ruins, surrounded by urban development. The architectural features of the church include round arches and polygonal columns, reflecting the design of other Portuguese-era churches. Although the main altar was moved elsewhere, an annual mass is held at the site today as part of ongoing preservation efforts.

![St. John the Baptist Church in Andheri is a fine example of Portuguese Colonial architecture.[4]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai-suburban/architecture/st-john-the-baptist-church-in-an_XcDjww4.png)

Castella de Aguada

Castella de Aguada, also known as Bandra Fort, follows the Indo-Portuguese coastal defence architectural style. It was built in 1640 by the Portuguese in the western suburb of Bandra. The fort was constructed after the defeat of Bahadur Shah of Gujarat to serve as a watchtower. It overlooked Mahim Bay, the Arabian Sea, and the southern island of Mahim. The fort was later partially destroyed by the British in the 18th century to prevent its use by the Marathas as a forward base for attacking British-controlled Bombay. Though now in ruins, parts of its ramparts and walls remain. The fort is also known for its proximity to the Bandra Bandstand, making it a popular heritage and recreational site today.

![Castella de Aguada showcases Indo-Portuguese architecture suited to its coastal location.[5]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai-suburban/architecture/castella-de-aguada-showcases-ind_AUwNj19.png)

Basilica of Our Lady of the Mount

The Basilica of Our Lady of the Mount, or Mount Mary Church, is an important example of Gothic Revival architecture in the Mumbai Suburban area. Situated atop a hill in Bandra, the church overlooks the Arabian Sea and has served as a landmark of faith and identity since the colonial era. Originally a small mud chapel built by Jesuit priests in the late 15th century, the church was reconstructed in 1761, and was finally completed in 1904.

Mount Mary Church is designed in the Gothic Revival style, which became prominent in Mumbai during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The church features pointed arches, ribbed vaults, stained-glass windows, and towering spires that evoke the ecclesiastical architecture of medieval Europe. These elements were adapted to the local context using indigenous stone and craftsmanship.

![Mount Mary Church features twin spires and pointed arches, typical of Gothic Revival architecture.[6]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai-suburban/architecture/mount-mary-church-features-twin-_SdUbJqF.png)

The facade is marked by twin spires, lancet windows, and ornate tracery. The main entrance features a large pointed arch and is flanked by pilasters and decorative stone carvings. The use of stained-glass panels adds both colour and symbolism, with biblical scenes rendered in vibrant detail. Ribbed vaults and flying buttresses support the ceiling structure and add to the building’s verticality.

The interior layout follows a cruciform plan, with a central nave that leads the eye towards the high altar, which houses the revered statue of the Virgin Mary. The altar is adorned with intricately carved woodwork and gilded details, surrounded by side chapels and frescoes depicting scenes from the life of Mary and Christ. The flooring features geometric tilework—a blend of British design and local craftsmanship—while the timber benches and decorative ceilings contribute to the sense of reverence and scale.

![At Mount Mary Church, a central nave and cruciform plan lead to the statue of the Virgin Mary.[7]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai-suburban/architecture/at-mount-mary-church-a-central-n_VzHotqa.png)

The steps and open grounds surrounding the church form a transitional zone between the sacred interior and the public space outside. These areas play a key role during the annual Bandra Fair, which attracts thousands of pilgrims, reinforcing the church’s place as both a devotional and social space.

The Capital, Bandra Kurla Complex

In recent decades, Mumbai’s architectural evolution has paved the way for a new style shaped by the city’s growing status as India’s financial capital. This commercial function led to the development of business districts like the Bandra Kurla Complex (BKC), where architecture shifted toward contemporary designs that prioritize scale, efficiency, and urban visibility. The Capital, a prominent tower in BKC, captures this transformation. Designed to meet corporate demands, its glass façade and selective environmental features reflect a global architectural language rather than a local one. Its form and function suggest a city increasingly focused on visibility, exclusivity, and branding, with less emphasis on integrating public life into its built spaces.

![The Capital’s west façade features a stepped glazed design with cantilevered floors for self-shading, while the east sky lobby showcases an egg-shaped structure.[8]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/mumbai-suburban/architecture/the-capitals-west-facade-feature_Xn6eS16.png)

The Capital features a stepped-in glazed valley façade on its western elevation, where cantilevered floors supported by feature columns create a self-shading structure. On the eastern side, an egg-shaped structure enclosed within a sky lobby is flanked by natural waterfalls and vegetation that enhance cooling and provide scenic communal space. The façade incorporates triple-layered glass for heat and sound insulation, while polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)-coated cladding offers durability, UV resistance, and low maintenance.

The building’s design integrates cybertecture (integrating technology and architecture to create intelligent, interactive and dynamic built environments) principles while maintaining form and elegance. LED strips across the façade function both as digital display elements and as sun-shading devices. Interiors include luxury coworking spaces alongside 24-hour access and high-speed internet to support continuous business activity.

As a whole, Bandra Kurla Complex stands as a symbol of contemporary Mumbai—combining green architecture, smart infrastructure, and dynamic urban planning to create a district that aligns with global standards.

Residential Architecture

In Mumbai’s suburbs, as in any region, local history and socio-cultural and economic dynamics have played a significant role in shaping the district’s architectural character. The modern day landscape of the suburbs and metropolitan region of Mumbai today, is often described by architects and urban planners as a ‘city under construction’, with countless projects underway.

The lesser-known stories, however, lay hidden, where ‘juna’ (old) homes stand as quiet witnesses to the past. As the city changes, these homes tell a tale of transition, offer a glimpse into the lives of people who have lived there and the story behind the homes that have stood the test of time.

The Late 19th - Mid 20th Century Homes of the District

The late 19th and early 20th centuries marked a turning point in the evolution of what is now the Mumbai Suburban district. While the name and identity of the district are commonly accepted today, their origins can be traced to this formative period. Much of what constitutes the suburban district today was originally part of Salsette Island, a separate landmass from the seven islands that formed the city of Bombay.

Salsette, described by George Curtis as the “adjoining island,” maintained its distinct identity well into the colonial era. Though acquired by the British in the 18th century, it was not until the 19th century that efforts to integrate Salsette with Bombay gained momentum. These efforts were part of a broader strategy of urban expansion that would lay the groundwork for a unified metropolitan identity. In a 1914 report, the Bombay Development Committee described Salsette as essential to the city’s future, “Salsette development is so closely connected with the development of Bombay that we should like to call attention to certain matters affecting Salsette, since that island will after all be part of the Bombay of the future.”

By the mid-20th century, these intentions had materialised. The once-clear boundary between the city and its suburbs gradually blurred, culminating in the establishment of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region, which administratively and ideologically linked the two.

The architectural development of the suburban district during this period was not incidental. It was shaped by colonial planning, demographic pressures following events such as the plague, and an urgent need to relieve congestion in the southern parts of the city. These motivations were often aligned with the broader logic of spatial separation along class and occupational lines, a pattern still evident in the structure of Mumbai’s suburbs.

Many of the residential forms that emerged during this time reflect the architectural thinking of the colonial government. While many of these structures have been modified or replaced as redevelopment continues, a few remain embedded within the urban fabric. These buildings, whether preserved or in transition, retain traces of the planning, materials, and design sensibilities that defined a significant period in the district’s development.

A Residential Space at Mahatma Gandhi Road, near Mulund Station (W)

In Mumbai’s residential areas, especially in older suburbs like Mulund, it is common to hear the phrase: “Yeh jagah purani hai, bahut purani,” this place is old, very old. A similar sentiment surrounds a residential structure situated just outside Mulund Station (West). Though periodically renovated, the building is believed to be around 150 years old, and continues to serve as a lived-in space.

It is an open secret that the doorway into many residential properties in Mumbai lie in its congested gallis. The streets of Mulund Station markets consist of endless lanes, bylanes, and alleys which enclose within them street stalls, commercial buildings, and residential properties.

Many older houses in this locality, including the one discussed here, are accessed through these gallis. While it is unclear whether the structure originally included commercial use, a sugarcane juice shop currently located on the ground floor has been operating for approximately 50 to 60 years, according to local accounts.

Pranjali Mathure notes in her article “Affluence, Aspiration and Art Deco in Salsette: The Story of Bombay’s Once Northern Neighbour” for Art Deco Mumbai, Mulund was among the earliest suburbs in the district to be developed through formal planning. A key feature of this planning effort is still visible in the area’s rectangular network of interconnecting lanes that orient from the station, which continues to define much of the neighbourhood’s layout.

This gridiron pattern was introduced in 1922, when German architects and planners were commissioned to design a plan extending from Mulund Station to Paanch Rasta. The presence of industries west of the station spurred concentrated development in that direction. The street network, said to have been commissioned by local zamindar Jhaverbhai Narottamdas and executed by the German firm Crown & Carter, was created to improve access to these workplaces.

The design of the residence is much in line with the tradition of the time. It has a symmetrical elevation meaning that both the doors and windows are aligned at the same height. The structure comprises arched doors and windows with vents, symbolic of a lost element that was a prominent architectural feature in the bygone era.

The materials used that can be prominently seen are wooden, captured in the lines that shape the gable end (again a lost element) and balcony walls. The roof structure of the site features a sloping roof made up of clay tiles and supported by wooden beams. This feature suggests that its integration into the structure was specifically designed to manage rainwater during Mumbai’s heavy monsoon seasons.

A Residential Space near Mulund Station (W)

Located behind a row of street stalls, this residence near Mulund Station (West) is estimated by locals to be over 100 years old. The structure is now part of a redevelopment project, and currently appears somewhat detached from its surroundings, partly concealed and set back from the main street.

The ground floor features multiple doors and windows, suggesting the structure may have once housed separate tenement-style units. The layout of the door openings, each with its own entry, points to multiple occupants or tenant families living independently within the same building.

The upper-level railings are made of iron, with wooden panels beneath that may have served as shading or ventilation devices. The window vents, framed in glass set within wooden borders, remain visible on the upper floor, hinting at the layered materials once commonly used in residential construction.

Some of the doors retain decorative carvings or painted patterns, possibly reflecting the aesthetic preferences or cultural background of former residents. The placement of windows and doors follows a symmetrical rhythm, with iron grill vents above.

The staircase, located just off the main entrance, rises along the interior wall and connects the two floors without encroaching on shared circulation space.

The lower structure of the entrance area (plinth and flooring) seems to have been constructed by stone. The flooring of the first story seems to be constructed of wooden planks. The walls are made up of bricks. The wooden beams in the structure of the bottom floor, as one can see in the image above, support the flooring of the upper floor.

An adjacent house, located in the same lane, shows similar construction. The plinth level is also made of stone, with brick masonry walls above. Beneath the sloping tiled roof, a triangular wooden carving is placed just below the gable, a detail that may have served a decorative or symbolic function.

Interestingly, this same triangular carving is also seen in a house located deeper within the lane network branching off Mulund Station (W), suggesting a shared design vocabulary across otherwise scattered residences.

Another common detail observed is a brick arch over a window lintel, such as in the example of a white-painted window nearby. These features, though understated, perhaps can offer insight into the architectural patterns once prevalent in the area.

Igloo Houses for Cement Factory Workers in Mulund

Tucked into the narrow bylanes that lie near the Ashok Nagar locality in Mulund are a few remaining examples of what locals refer to as “Igloo Houses,” a term that emerged from the distinctive curved shape of their corrugated roofs. These structures are believed to have been built to house workers employed in nearby cement factories. While the exact date of construction is unclear, residents estimate them to be around 80–90 years old, possibly built in connection with the Cement Factory established in the the 1930s, during a period when Mulund was undergoing industrial transformation.

The lane where these houses sit are narrow and enclosed, lined with houses that are uniform in scale and layout. Each house shares a mirrored plan, and their corrugated sheet side walls directly meet those of adjacent units, creating a row of connected dwellings without gaps.

Although the materials are industrial (mainly corrugated cement sheets and simple brickwork) the design suggests an early effort at planned worker housing, built for efficiency and repetition. Internally, the houses follow a linear layout. Spaces are loosely defined rather than formally divided, with rooms opening into each other and few internal walls.

The roof structure extends seamlessly from wall to ceiling, forming a single curved surface. This treatment doesn’t reflect traditional vaulting in a historical sense, but rather an adapted use of corrugated sheeting, shaped to act both as roof and partial wall.

One of the houses, likely renovated more recently, sits at a slightly raised plinth level, making it level with the footpath. In contrast, the other two retain small entry steps leading up to their verandahs.

While these houses were clearly constructed for functional purposes, as seen in the repetition in layout and care in proportional arrangement. Today, these few remaining structures stand quietly within a rapidly changing neighbourhood, serving as a trace of Mulund’s industrial past.

Block Houses of Mulund Colony

Mulund Colony, located in the western part of the Mulund locality, is home to a small number of surviving residential units originally constructed for refugees following the Partition of India in 1947. Commonly referred to as “block houses,” these single-storey structures formed part of a broader post-Partition housing initiative, designed to accommodate displaced families who had moved through various camps in the Thane and suburban regions. As if to acknowledge this history, the locality, for many years, was popularly called Punjabi Colony or Sindhi Colony.

It is said that during World War II, this area had served as a military cantonment. Some residents recall that in the colony’s early years, displaced families lived in close proximity to army personnel. In fact, the influence of this military past remained in local memory: many still refer to these houses and parts of the area as “barracks,” a name likely reinforced by the uniform, utilitarian layout of the homes.

Each block originally comprised six conjoined houses, arranged side by side and separated from other blocks by narrow internal lanes (gallis). The houses typically included three rooms, a small front verandah, and shared architectural features across the colony.

Built on a sloping road, locally referred to as a chadaan, the houses followed the natural incline of the land, likely due to the colony’s location within a forested and hilly region. In earlier decades, locals recall that access from the main road involved stepping down onto paths made of mud and stone (mitti and pathar), with shallow steps leading to individual entrances.

The houses shared a consistent architectural style. Wooden windows with iron railings and upper ventilation slots were standard features.

Roofs were made of corrugated metal sheets supported by exposed wooden beams, without any false ceiling. Inside, walls often stopped short of the roof, allowing air and sound to pass through, creating partially open interior spaces.

Some parts of the colony, referred to as the “old barrack,” had clay tile roofs rather than corrugated metal ones. Though the internal layout remained largely the same, the roofing material created a visible distinction.

The older corrugated sheets used across the colony were different from those found today. Their ridges were separated by flat, straight sections at least ten inches wide. In contrast, locals say that the modern versions have closely spaced wave-like curves that form a continuous pattern. (refer to the image of the double roofing structure given below).

As the years went by, some residents began adding a second layer of roofing above the original to protect against the heavy monsoon rains. These double-roof structures, initially a practical solution, came to reflect socioeconomic differences within the community. Very notably, locals recall that those who could afford the upgrade distinguished themselves from others living under the original single roofs.

Inside the homes, the floors were often laid with shahabad ladi, a type of stone slab sourced from the Shahabad region in Karnataka, popular in the 1940s.

Over time, many residents began extending the spaces outside their homes, creating informal additions that served as transitional zones between the street and the interior. These extensions were often constructed using a mixture of clay and cow dung for the flooring—a traditional, affordable material that kept surfaces cool and grounded. Depending on the community, these spaces were referred to as aangans by many Punjabi families and thaalas by Sindhi families.

Although many of these original houses have been demolished or replaced by new construction, the few that remain offer a rare window into the architectural practices and everyday lives of those who rebuilt their worlds in post-Partition suburban Mumbai.

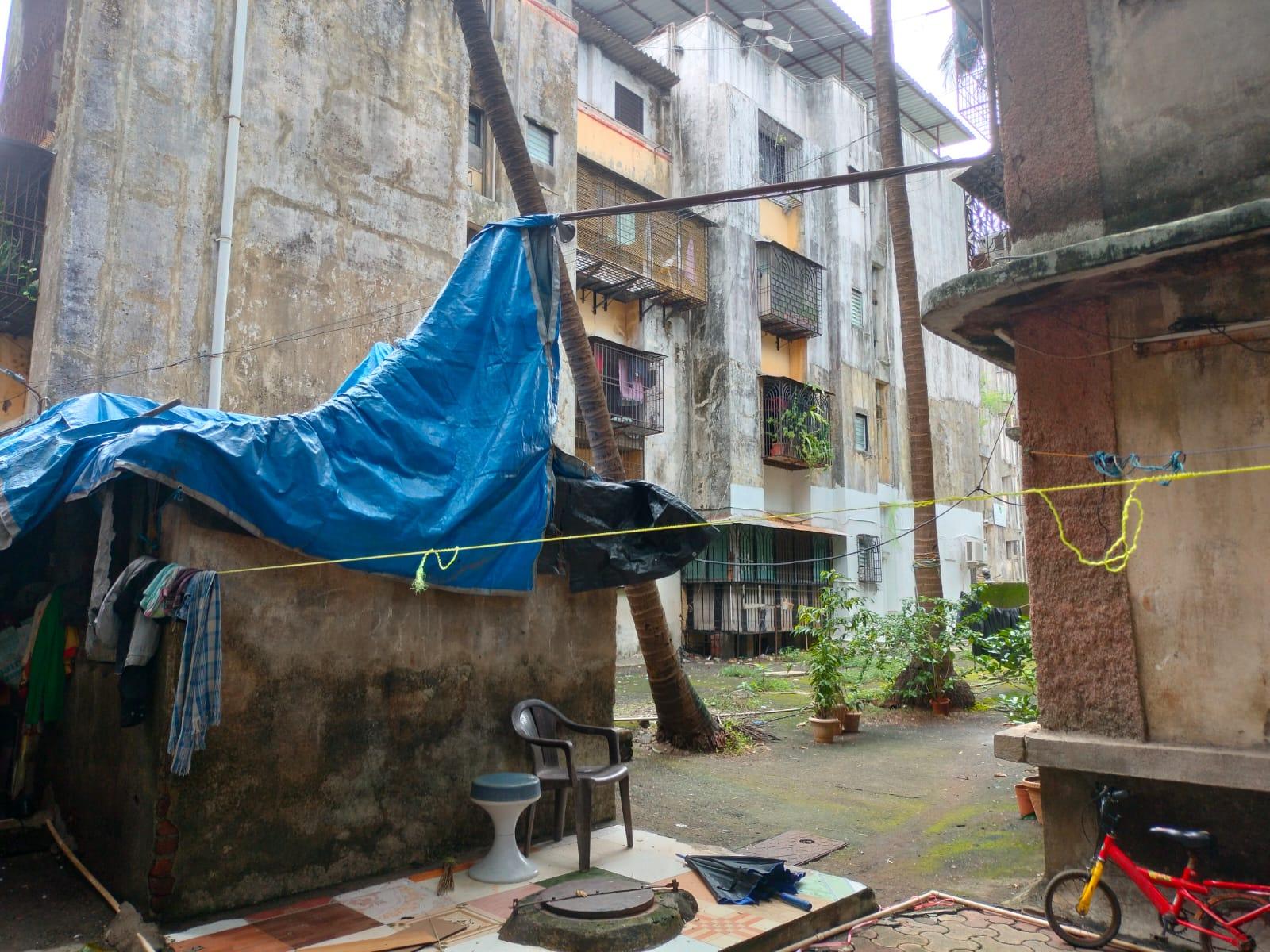

Homes of the 1980s: Apartment Spaces

By the 1980s, residential development in Mulund had begun to shift toward low-rise apartment buildings that responded to the growing needs of nuclear families and urban middle-class life. These structures marked a transition in both form and lifestyle, denser than individual houses, yet more personal than high-rise towers. It is important to note that while they once replaced older forms of housing in the name of progress, many of them now face a similar fate, aging, overlooked, and increasingly marked for redevelopment.

Girikunj

Girikunj is a housing society which is situated in the area known as Cypress in Mulund (W). The building is situated on a secondary lane accessible from a main road that slopes gently. The lane is intimate, lined with other residential houses that are closely similar in height. The two-storey building spans three levels, ground, first, and second, and has an accessible terrace.

Vertical circulation is provided through a staircase, as the building does not include a lift. The structure was built using reinforced cement concrete (RCC) and follows a compact layout suited to the urban residential needs of its time.

Each floor of the building contains three apartments. The two units on the left are 1 BHKs (one-bedroom, hall, and kitchen), while the unit on the right is a 2 BHK (two-bedroom, hall, and kitchen). Interestingly, the built-up area of each flat differs slightly, accommodating varying household needs.

One of the most recognisable features of the building is the concrete chajja, a projecting slab above each window that provides shade and visual continuity across the facade. This feature, standardized in post-independence housing by the Public Works Department.

The facade also incorporates a tied horizontal band and a corner section treated with textured finishes. The building is painted in a combination of yellow and red, with the red highlighting corners and edges.

The compound is enclosed by a concrete wall and accessed through two adjacent metal gates.

Girikunj shares its plot with another building that is estimated to have been constructed approximately a decade later. Residents say that although the two structures are physically connected, they are managed as separate societies, each with its own committee and infrastructure.

Each building also maintains its own utility infrastructure, including separate pump houses for water supply.

There are no formal amenities within the compound. Residents say that the open space was never developed as a garden, but over time, society members have planted Ashoka, baadam, and other trees along the perimeter. Notably, the site was once used as a local playground before being developed for housing.

At the rear of the building, a staircase leads to a closed-off section below. Residents explain that the builder had attempted to construct a basement or office space, but work was halted by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC). The unfinished staircase still remains, leading to an unused space beneath the structure.

Girikunj remains a functioning residential building that, in many ways, reflects the design, layout, and living patterns of post-Independence housing in suburban Mumbai.

Residences of the 21st Century

Golden Willows, Vasant Gardens

Golden Willows is a 17-storey residential tower located in Vasant Gardens, Mulund (West), developed by Sheth Creators. Set against the hilly backdrop of Mulund Colony, the building rises along roads that continue to follow the area’s natural topography.

Although significantly taller than its surroundings, the building incorporates elements intended to visually break down its mass. These include stacked balconies, cornice bands, and balustrades that give the facade a layered appearance.

Golden Willows integrates features associated with European classical architecture, particularly those drawn from neo-classical traditions. This includes Corinthian columns, pilasters, pediments, and entablatures. These elements are applied ornamentally to frame windows and balconies, and to articulate the upper sections of the building near the dome.

The building's fenestration is arranged in a symmetrical grid, with pilasters and cornice bands reinforcing this order. These alignments echo classical principles of proportion and repetition, though their application here is decorative rather than structural.

At street level, the base of the tower incorporates commercial shops. Residents note that this arrangement (residential towers with attached retail) has become increasingly common across newer developments in Mulund, reflecting mixed-use planning approaches.

The building uses earth-toned materials, with darker accents around openings and edges to emphasize its decorative detailing. While constructed using contemporary methods and materials, the tower shows how classical architecture can adapt to modern needs. It keeps its historical character while serving as a functional part of Mumbai’s contemporary urban landscape.

Sources

Adminhhsa. 2021. Know more about Chajja. Healthy Homes. Accessed on April 15, 2025.https://healthyhomes.co.in/know-more-about-c…

Akshita Chandak. Mount Mary Church, Mumbai. Rethinking The Future.https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/case-st…

Apurva Srivastava. 2020. Exploring the History and Significance of Jogeshwari Caves in Mumbai. Mumbai Live.https://www.mumbailive.com/en/culture/histor…

Bombay Development Committee. 1914. Report of the Bombay Development Committee. Government Central Press, Bombay.https://archive.org/details/ReportOfTheBomba…

George Curtis. 1921.The Development of Bombay. Vol. 69, no. 3582. Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, London.

Nitin Mhapsekar. Remains of Indo-Portuguese Architectural Layer in Mumbai. Rethinking The Future.https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/city-an…

Poorva Patil and Vaishali Latkar. 2022. Tracing the Evolution of Kanheri Buddhist Cave Complex, Salsette, Maharashtra. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology.https://www.ijert.org/research/tracing-the-e…

Pranjali Mathure. 2023. Affluence, Aspiration, and Art Deco in Salsette: The Story of Bombay’s Once Northern Neighbour. Art Deco Mumbai, Mumbai.

Preeti Chopra. 2012. Free to Move, Forced to Flee: The Formation and Dissolution of Suburbs in Colonial Bombay, 1750–1918.Vol. 39, no. 1. Urban History, Cambridge.

The India Cine Hub. Bandra Fort. The India Cine Hub.https://indiacinehub.gov.in/location/bandra-…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.