NASHIK

Architecture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Architecture of Prominent Sites

Nashik’s architectural heritage weaves together spiritual, monastic, and devotional traditions, reflecting its longstanding role as a religious and cultural center. Its prominent sites showcase a range of styles: from the rock-cut austerity of the Buddhist Pandavleni Caves to the restrained elegance of the Hemadpanthi Kalaram Mandir and the intricately carved Nagara-style Trimbakeshwar Shiv Mandir. These monuments represent centuries of cultural exchanges and shifting political powers, standing as enduring landmarks in a city where built architecture continues to shape urban identity.

Pandavleni Caves

The Pandavleni Caves, also known as Trirashmi Caves, follow the Buddhist architectural style and are located on Trirashmi Hill, about 8 km south of Nashik city. These 24 rock-cut caves were carved between the 3rd century BCE and 6th century CE, mainly under the patronage of the Satavahanas and Kshaharatas. They were built for Buddhist monks and represent Hinayana Buddhism.

![The Pandavleni Caves (Trirashmi Caves) follow Buddhist architectural style and are carved from locally available basalt rock.[1]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/nashik/architecture/the-pandavleni-caves-trirashmi-caves-foll_ThTE2am.png)

The Pandavleni Caves consist mainly of viharas (monastic dwellings) and one chaitya griha (prayer hall). The viharas include small cells with stone beds, open courtyards, and verandas, while Cave 18, the chaitya griha, contains a stupa for communal worship. The caves face north, protecting their carvings from sun and rain for over 1,500 years. Their architecture uses locally available basalt rock and incorporates water tanks carved into the stone to store rainwater.

![Interior of Cave 18, the chaitya griha, showing the central stupa and supporting pillars used for communal worship.[2]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/nashik/architecture/interior-of-cave-18-the-chaitya-griha-sho_JvKctkI.png)

Cave 3 stands out as the largest and most elaborately decorated, featuring a grand entrance, spacious chaitya griha, and detailed carvings of Buddha and Buddhist symbols. The walls and pillars across the caves hold inscriptions in Brahmi and Prakrit scripts, recording donations from kings, traders, and monks.

![The entrance of Cave 3, the largest and most elaborately decorated cave, known for its spacious prayer hall and intricate carvings of Buddha and Buddhist symbols.[3]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/nashik/architecture/the-entrance-of-cave-3-the-largest-and-mo_7JMiOQr.png)

Kalaram Mandir

Kalaram Mandir follows the Hemadpanthi style of architecture and is located in the Panchavati area of Nashik. The Mandir is believed to have been built over 12 years between 1782 and 1794 under the patronage of Sardar Rangrao Odhekar. It stands on a site where it is believed Bhagwaan Ram lived during his exile, as narrated in the epic Ramayan. The Mandir is constructed in black stone and houses black stone murtis of Ram, Sita, and Laxman, each about two feet tall, giving the Mandir its name, “Kalaram.” The structure features minimal ornamentation, in keeping with the Hemadpanthi style, prioritizing functionality over elaborate decoration.

![Kalaram Mandir, built in black stone, follows the Hemadpanthi style with minimal ornamentation and a focus on functional design.[4]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/nashik/architecture/kalaram-mandir-built-in-black-stone-follo_rnoqKQc.png)

Trimbakeshwar Shiv Mandir

Trimbakeshwar Shiv Mandir primarily follows the Nagara style of architecture and is located in Trimbak, about 30 km southwest of Nashik. The Mandir was commissioned by Peshwa Balaji Baji Rao in 1755 and completed over several decades, using black basalt stone found locally. It stands within a large walled courtyard and houses one of the twelve Jyotirlings of Bhagwaan Shiv, making it a major yatra site.

![Trimbakeshwar Shiv Mandir, built in local black basalt stone, follows the Nagara style with Hemadpanthi influences.[5]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/nashik/architecture/trimbakeshwar-shiv-mandir-built-in-local-_0DA6zCi.jpg)

The Mandir’s architecture reflects some features from the Hemadpanthi tradition, incorporating local basalt stone and lime with intricate stone carvings covering its Vimana and exterior walls. The carvings depict floral patterns, scrollwork, humans, and animals, among others. The Mandir lies at the base of Brahmagiri Hill, the source of the Godavari River, and is surrounded by the Nilgiri, Brahmagiri, and Kalahari hills. Within the Mandir complex is the Kushavarta Kund, a sacred tank marking the river’s origin.

Residential Architecture

In Nashik, each structure carries the imprint of local history, community life, and a distinctive cultural identity of the district’s many inhabitants. They also carry within them the traditions and ways of living of the time they were built in. Over time, Nashik’s architecture evolved from the wada-style homes built during the Peshwa period to later colonial influences under British rule, reflecting changing patterns of settlement and lifestyle. As time passes, it is fascinating to see how the private space of ‘home’ has been reimagined across different eras, often affected by the larger ‘public’ events that take place outside of it. In today’s Nashik, as urbanization transforms parts of the district and its ways of living, traditional homes and lifestyles also remain; their architecture tells stories of the past that shaped them.

A Mid-19th Century Home in Askheda

Ashkheda is a small village that lies within the Satana taluka. Among the many landmarks that the village is known for is the ‘Icchapurti Ganesh Mandir.’ At the center of this village and just beside the Mandir lies a single-storeyed house, estimated by locals to have been built in 1949.

The residence occupies an area of 1800 sq ft. and was built using teakwood and mud. A joint family resides in this house, and interestingly, its design accommodates their living arrangement. The house features a mud wall that divides it into two sections. This design, in many ways, provides privacy for different members of the joint family who share the residence.

The architectural features of the house are quite striking and unique, many of which appear to have been designed considering the area’s local environment. For instance, the house features a notably elevated plinth, which, according to local residents, was designed to prevent waterlogging during heavy rains.

The doors of this residence are adorned with heavy, thick teak wood with iron spikes, similar to those found in the historical ‘Wadas’ of Maharashtra. The entrance door is a solid, teak-wooden door that spans approximately 6 to 7 ft. in height.

A secondary safety door is placed in front of the main entrance, intended to prevent young children from leaving the house and to keep stray animals from entering. Locals say that this feature can be commonly found in the village.

Another interesting design element that can be found on the doors of this village is tied to a cultural belief. According to locals, ‘horseshoe plates’ are believed to ward off evil spirits. Hence, they are usually placed at the front side of the door to serve as a protective element.

The construction of the house aligns with the principles of ‘Vaastu Shastra.’ The house faces east, which allows for direct sunlight to enter the front passage, a feature considered to be auspicious and pleasant. The layout of the house is noteworthy. The kitchen is positioned to the northwest of the house. The bathroom and the washroom are situated at the extreme end, separate from the main house. Near this space is the ‘aadh’, which serves as a source for water storage and use.

Interestingly, one can see the many ways in which the social conditions of the time seep into the spatial arrangement of the house. The rectangular main hall, known as Baithak Kholi (sitting room), is designated for the Karta (colloquial term for the patriarch) and elders to engage in discussions. Other members of the family were rarely allowed to sit there, which reflects the importance shown to the ‘Karta’ of the house.

Beyond the hall is another room where various domestic activities, such as grain sorting (dhanya nivadne), using a mortar and pestle (ukhal-musal), blanket stitching (godhadi shivne), and vegetable cleaning (bhaji suavne), were carried out. This area was, notably, primarily used by women, while the Karta is said to have rarely entered this space.

The cupboards of the home are built into the wall and are quite spacious. The main hall has cupboards on either side of a wooden beam and one positioned at a lower height. The higher cupboards likely stored less important/used things of the household while the lower cupboard might have been used to keep the daily essentials.

Saanas, which are carved into the wall, are used to place things which are used daily like lanterns or diyas. This house has one Saana installed on the door frame of the second room. It is situated in a prime location of the house, from where the light of the diya could illuminate the room.

The roof of the house is constructed using wood and soil. A strong support of teak wood beams helps strengthen the structural foundation of the roof, and later plates of wood are laid to complete the roof.

Soil is layered over the structure to provide adequate weight. Over time, as the roof required maintenance, plastic papers were additionally layered on the soil to make the roof resistant to water. Some areas at the front of the house have been reinforced with tin sheets and cement for added protection.

There are many motifs which can be found throughout the house. The pilasters, which support the roof of the house, are carved with unique and intricate art. Interestingly, there is a carved plate of Ganesh, the same Devta which is worshipped at the Icchapurti Ganesh Mandir located to the left side of the house. This, in many ways, might indicate the many ways in which faith has been incorporated into the architecture and design of the house.

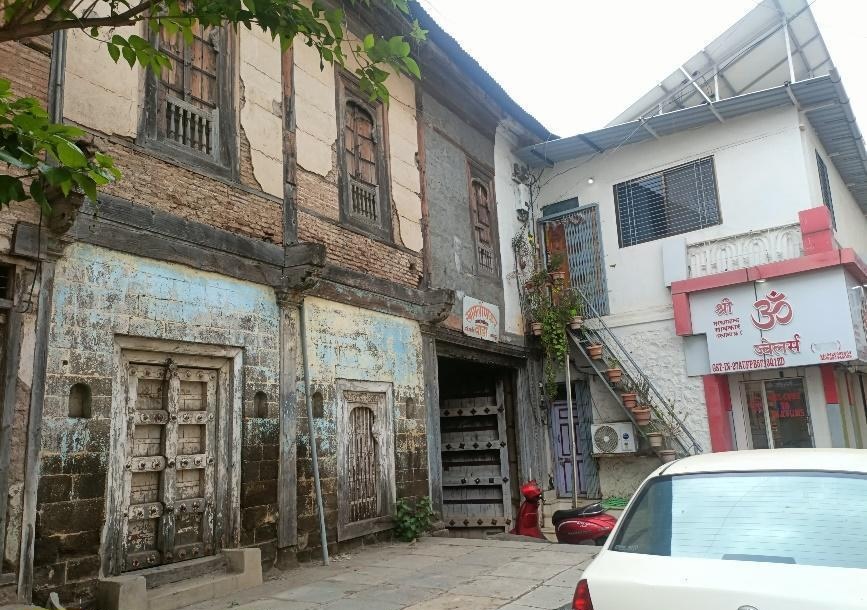

A 20th Century Wada in Sonar Galli

‘Sonar Galli’ is a semi-commercial area in the Nampur town of Satana taluka, which has gained its name from the presence of a cluster of jewellery stores in the area. Within this galli lies a two-storey wada, which is estimated to have been built in the early 1920s. The wada is a massive north-facing residential building that spans over an expansive 2000 sq. ft. The wada has long been home to the Khamlonkar family, who were jewelers by profession. Notably, this history is the reason why the house is known as Khamlonkar wada.

The wada continues to be a centre of attraction for the entire town owing to its stunning architecture and its unique wood carvings. An interesting aspect of the wada is how the composite structure (a technical term used to describe the materials used to build a residence) of each storey is different. The first floor was constructed using rocks while the second floor utilised cement bricks.

The entrance of the wada features an imposing wooden gate, standing 10-15 ft. tall, which has a medieval fort-like character to it. This character has, in many ways, led to the entrance gate to have various distinct elements within it. One such element is that a smaller opening has been created at the left side of the door. As the gateway seems to be colossal in both its height and weight, for everyday convenience, locals say that this opening served a functional purpose in the exchange of household goods.

Other than that, there are many other gateways that lie at the entrance of the house. Interestingly, one of these entrances, it is said, leads to a small room which served as a space where outsiders could conduct business without entering the main residence.

The main entrance into the wada opens to a courtyard. At the center of this courtyard lies the Tulsi Vrindavan (a small podium present in many traditional households holding the sacred Tulsi plant), with its placement, notably, being a characteristic element of many wadas.

Some other characteristics of the Wada architecture can also be found in the windows of the house. Notably, ‘sanas’, which are curved elements that are carved into the house, can be seen at the top of many windows at the entrance. Other than this, a noteworthy aspect of the wada’s design is the woodwork that can be seen across the house, especially when it comes to the railings and the pillars of the house. Interestingly, unique designs such as horses and many other geometric patterns can be seen carved across the wada.

A Bungalow of the 2020s in Ghadge Mala

As time passes, one can usually see how new architectural styles gradually begin to reshape the region’s landscape. In Makhmalabad, there are many areas where one can spot this transition. In the neighborhood of Ghadge Mala, a triple-storeyed bungalow lies that was constructed in 2022. The bungalow is approximately 4000 sq. ft. and is home to a joint family.

The bungalow is in line with the present-day housing elements commonly found across many urban regions in India. The composite structure is made of RCC cement. The entire flooring of the house is tilled with marble.

The entire house, in many ways, showcases how present-day architecture has evolved and how it differs greatly from the past.

Sources

Aaradhya Yadav. 2024. Pandavleni Caves: Ancient Marvels of Nashik’s Rich History. Historified.https://historified.in/2024/11/19/pandavleni…

Behind Every Temple. Triambakeshwar Temple. Behind Every Temple.https://behindeverytemple.org/hindu-temples/…

Fatima Hamid. 2022. Trimbakeshwar Shiva Temple. Sahapedia.https://map.sahapedia.org/article/Trimbakesh…

Incredible India. Pandavleni Caves. Incredible India.https://www.incredibleindia.gov.in/en/mahara…

Nirantari Shinde. 15 Places to Visit in Nashik for Travelling Architect. Rethinking The Future.https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/travel-…

Rishika Sood. Architecture of Indian Cities Nashik - Culture along the banks of Godavari. Rethinking The Future.https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/rtf-fre…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.