Contents

- Ancient Period

- The Ancient Urban Centre of Sopara

- Sopara’s Connection to Buddhism & the Story of Purna

- Mauryan Period and the Ashokan Edicts

- Satavahanas and Western Kshatrapas

- The Chinchani Copper Plates and the Port of Sanjan

- Gradual Rise of Vasai

- Jawhar Kingdom

- Medieval Period

- Portuguese

- Treaty of Bassein / Vasai, 1534

- Vasai Fort

- Spread of Christianity

- Vasai Plague

- Decline of Portuguese Control

- The Maratha Conquest of Vasai

- Marathas and the Jawhars

- Colonial Period

- Colonial Administrative changes

- Jawhars Under Colonial rule

- World War II onwards

- Environmental Changes in Dahanu

- Sugar Making: Traditional and Colonial

- Cocoa-Palm Farming in Dahanu

- 1875 Cholera Outbreak

- Struggle for Independence

- Portraiture and the Case of Ramchandra Mahadev Churi

- Post-Independence

- Agricultural Developments

- Chikoo Cultivation in Dahanu

- Wada Kolam Rice in Wada

- Industrial and Technological Infrastructure

- Sources

PALGHAR

History

Last updated on 18 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Palghar district, lying along the western coast of Maharashtra, has historically derived both economic and cultural significance from its maritime position. Like many other coastal districts, its location fostered early connections with distant lands, influencing its culture, economy, and way of life. The ancient port of Sopara, identified with Shurparaka of Buddhist tradition, is said to have been visited by the Buddha himself and served as a centre of trade and religious activity under the Mauryan and Satavahana dynasties. Numerous archaeological finds attest to the antiquity and importance of the region in early historical periods.

In the medieval and early modern period, Palghar saw the rise of local powers alongside foreign influence. The Kingdom of Jawhar, ruled by a line of Koli and Warli chiefs, maintained authority over parts of the interior and preserved indigenous customs. Along the coastal belt, the Portuguese established a number of forts and churches, some of which remain standing, bearing witness to a period of European presence and control. Administratively, Palghar was quite formed fairly recently as a new district and had remained part of the Thane district until 2014.

Ancient Period

The Ancient Urban Centre of Sopara

The region now comprising Palghar district appears to have enjoyed a considerable degree of prosperity in early times, much of which can be traced to the presence of active coastal settlements and ports. These provided outlets for inland produce and entry points for maritime exchange, linking the North Konkan coast with distant trading zones across the Arabian Sea. Among such settlements, Sopara, referred to in earlier texts as Shurparaka, held a position of particular note.

Identified as the present-day town of Nala Sopara in the Vasai-Virar area, Sopara is described in several early literary and religious sources. It is mentioned in the Mahabharat as a tirtha, and assigned in the Skanda Purana, as a place of ritual and geographic significance along the western seaboard. Over time, the site appears to have acquired both religious and commercial importance, serving as a local capital in Aparanta (the North Konkan region).

Sopara is widely acknowledged as one of the most important port towns on India’s western coast, second only to Cambay (Khambhat in Gujarat). Through much of the early historic period, Sopara maintained active commercial ties with regions such as Mesopotamia, Egypt, Cochin, Arabia, and Eastern Africa, and was counted among the largest and most active settlements on the coast.

Some classical sources, particularly from Phoenician traditions, refer to a place called Ophir or Sophara, which several scholars have linked to ancient Sopara. If this identification is correct, it would suggest that the port was known as early as the 1st millennium BCE, during the height of Phoenician maritime activity in the eastern Mediterranean and Indian Ocean.

The Thane district Gazetteer (1882), referencing early literary sources, notes that the chief exports from Sopara included gold, tin, sandalwood, cotton, nard, bdellium, sugar, cassia (cinnamon), pepper, rice, peacocks, apes, ebony, and ivory. That such goods were shipped from this coast suggests not only an active local economy but also a wider commercial system in which Sopara functioned as a collecting and distributing point for both foreign and inland markets.

Sopara’s Connection to Buddhism & the Story of Purna

Sopara also appears to have held considerable religious significance, particularly in connection with early Buddhism. Literary traditions, supported in part by later accounts, associate the town with the life and travels of the Buddha and his early disciples. Though these references are legendary in nature, they suggest that the town held considerable religious significance in antiquity and was regarded as an early site of Buddhist activity in the western Deccan.

The association of Sopara with Buddhism can be traced to one of its earliest literary mentions in the story of Purna, also known as Purnamaitrayaniputra. He is described as the son of a wealthy merchant of Sopara and a maidservant, who renounced his position and family fortune to take to the teachings of the Buddha. His story is found in the Divyavadana, a Sanskrit anthology compiled in the early centuries CE, and later preserved in Nepalese and Tibetan (translated by Burnloaf) versions dated to the third and fourth centuries CE.

According to these sources, Purna encountered the Buddha at Shravasti, where he requested permission to return to Aparanta (the name used for the coastal tract of the North Konkan) to preach the Dhamma. The narrative states that he did so successfully, and that Sopara, his native town, became a centre of Buddhist teaching under his efforts.

At the time of his return, Sopara is described as a large and fortified city, with a moat and seventeen gates, a marketplace, palaces, and monastic establishments. The text records that Purna, after becoming renowned as a teacher and miracle-worker, once calmed a storm at sea, earning the gratitude of a group of merchants. These merchants, in turn, constructed a Buddhist temple at Sopara and invited the Buddha to visit. He, accompanied by his many disciples, is said to have visited Sopara and, along the way, performed various miracles.

The persistence of Sopara as a site of Buddhist activity is supported by material evidence from later centuries, including relics, stupas, and inscriptions, which point to continued patronage and monastic settlement over time. The first major excavation at Sopara was undertaken in April 1882 by the famous archaeologist Bhagwanlal Indraji. He is said to have journeyed to the Burud Rajache Kot mound in the village of Merdes, near Sopara, and unearthed the remnants of a once-grand Buddhist Stupa buried beneath the Earth's surface.

Among the more notable finds from this excavation was a relic chamber containing a variety of ritual objects. These included reliquaries made of copper, silver, crystal, stone, and gold, along with a begging bowl. Perhaps most striking were eight bronze images discovered within the chamber. Of these, six represented past Buddhas: Vipasyi, Shikhi, Vishvabhu, Krakucchanda, Kanakamuni, and Kashyapa, while the remaining two depicted Shakyamuni (the historical Buddha) and Maitreya, the future Buddha. A portion of these finds is now housed in the Royal Asiatic Society’s Mumbai collection.

Mauryan Period and the Ashokan Edicts

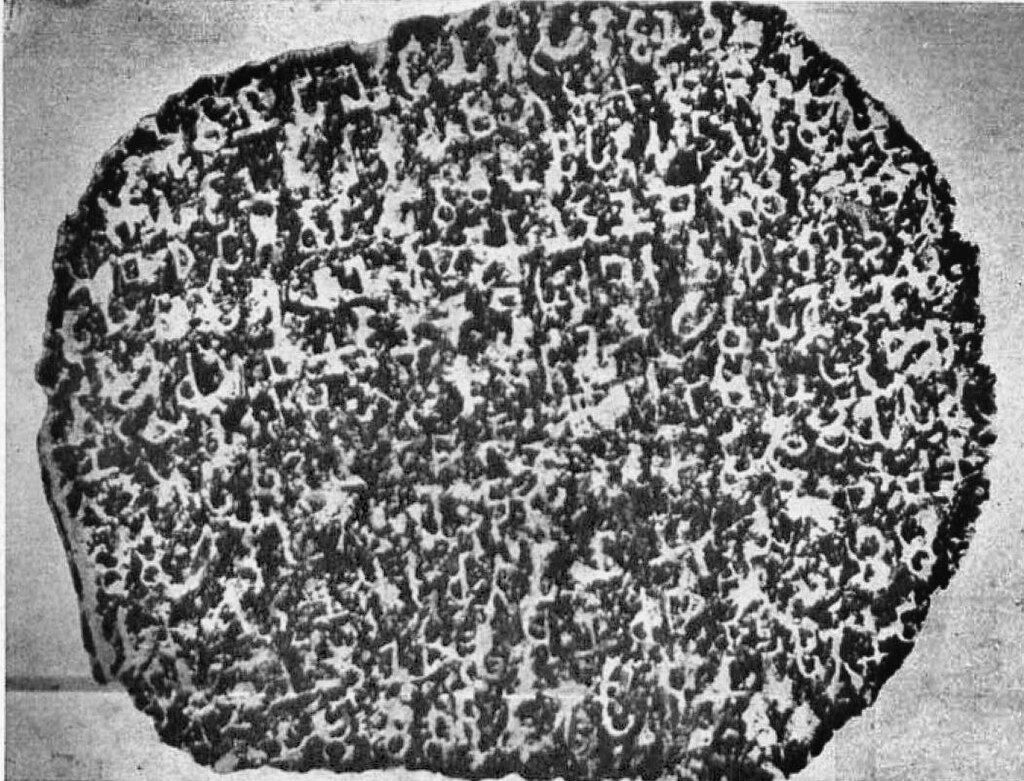

The earliest known political entity to have exerted some influence over the region comes from the Mauryan Empire. Inscriptions found at Sopara attest to the influence of Emperor Ashoka in this part of the Konkan coast. In 1882, Bhagwanlal Indraji discovered fragments of Ashoka’s 8th and 9th Major Rock Edicts in a graveyard near Ramkund, not far from present-day Nalasopara. Written in Brahmi script, these edicts provide insight into Ashoka’s religious policy, including his promotion of Dhamma and ethical behaviour.

The edicts were later housed in the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, Mumbai. In 1956, a fragment of the 11th Major Rock Edict was also recovered from Bhuigaon, a coastal village nearby. These discoveries, along with the earlier Buddhist relics found in Sopara, confirm the town’s inclusion within the Mauryan sphere of influence, likely as part of the western coastal tract known to ancient texts as Aparanta.

Satavahanas and Western Kshatrapas

Following the decline of the Mauryas, the region fell under the sway of the Satavahana dynasty, which maintained control over much of the Deccan. The discovery of a silver coin bearing the name of Gautamiputra Satakarni, found during excavations at Sopara, suggests administrative and commercial links between this area and the wider Deccan polity. During this period, Sopara continued to operate as a port of regional importance, facilitating trade across the Arabian Sea.

Control of this stretch of coast was contested. In the 2nd century CE, the Western Kshatrapas, under Nahapana, are believed to have taken control of North Konkan, only to be repulsed in turn by Gautamiputra Satakarni. Later, by the end of the 2nd century CE, the region came under the Kshatrapa ruler Rudradaman I, who briefly reasserted influence in the area. Such shifts reflect the economic and political importance of the North Konkan coast, particularly its ports.

The Chinchani Copper Plates and the Port of Sanjan

By the mid-6th century CE, the Chalukyas of Badami had expanded their rule into parts of the Konkan. This movement of power southward into coastal Maharashtra coincided with the weakening of northern control and the emergence of local chiefs and feudatories. According to traditions preserved in the Thane District Gazetteer (1882), by the early 7th century, a local ruler named Jadav Rana, identified as a Yadava chief, may have governed the coastal region around Sanjan. He is said to have granted refuge to a group of Persian émigrés fleeing the collapse of the Sassanian Empire: a claim echoed in Parsi oral traditions.

A major source of information on this period comes from the discovery of nine copper plates in Chinchani village, near Dahanu, in 1955. On 28 June 1955, a farmer in the village uncovered a set of nine inscribed copper plates while working his field. These were later forwarded through the local Mamlatdar and district offices to the Directorate of Archives in Mumbai. Historian and epigraphist D.C. Sircar examined them during his visit in 1957 and identified them as a series of five separate land grants, ranging in date from 926 to 1053 CE.

Together, these inscriptions provide a continuous record of over a century of political and religious life in the region, specifically tied to the port town of Sanjan, which lies just north of Chinchani. The earliest two plates belong to the reigns of Rashtrakuta emperors Indra III and Krishna III, followed by a third from the Shilahara vassal Chamundaraja, and two final grants issued by members of a hitherto unknown ruling house: the Modhas.

Of particular interest is the first plate, dated to 926 CE, which records a grant issued under the authority of Indra III. It identifies the governor of the region as Madhumati Sugatipa, a Tajik (Arab) administrator appointed by Krishna II. This may be one of the earliest recorded instances of an Arab Muslim holding a provincial governorship in the Indian subcontinent. The inscription further records that this governor granted land to a local citizen to support a temple dedicated to Bhagavati Devi, and references a Zoroastrian community assembly (anjuman) active in the town.

The later plates continue the story of this temple institution, referred to as a mathika, and its role in the religious life of the region. The fourth and fifth plates, issued by Modha rulers in the mid-11th century, mention continued endowments to the mathika and provide information on local landholding patterns, taxation, and the presence of settled merchant and religious communities, including Parsis and Brahmins from nearby Thane.

Taken together, the Chinchani copper plates offer rare insight into a pluralistic society in the early medieval northern Konkan: one where Arab governors, Hindu temples, Jain merchants, and Zoroastrian assemblies coexisted. The continuity of references across different dynasties suggests the enduring significance of Sanjan as a religious and commercial centre during this period.

Gradual Rise of Vasai

Vasai (historically known as Bassein) first enters the historical record in the 6th century CE, when Cosmas Indicopleustes, a Greek merchant, notes coastal trade in the region. By the 7th century, Xuanzang, the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim, passed through the western coast and made indirect reference to settlements in the vicinity.

During the 8th to 11th centuries, Vasai was likely governed in succession by the Silaharas of Konkan and later the Yadava dynasty. While earlier settlements like Sopara and Sanjan had long been dominant, Vasai's importance rose gradually owing to its proximity to natural harbours, river routes, and its defensible terrain. By the 12th century, Vasai had become a fortified settlement of note, eventually surpassing its neighbours in strategic relevance. It would only go on to gain much more significance later (which will be discussed in detail below).

Jawhar Kingdom

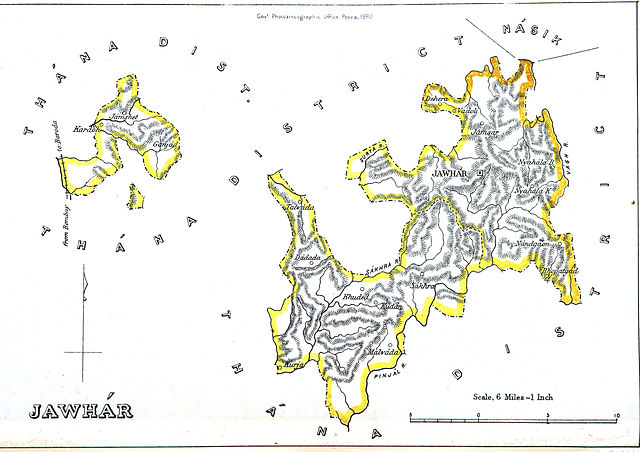

While coastal settlements such as Vasai gained prominence between the 8th and 12th centuries through maritime trade and fortified expansion, the forested inland hill tracts to the northeast developed along a different trajectory. In these upland regions, buffered by difficult terrain and distant from the coastal powers, local ruling houses emerged with limited external interference. Chief among them was the Mukne family of Jawhar, whose polity would endure from the early 14th century until the mid-20th.

The early history of this area is associated with Koli and Warli chiefs, whose influence extended across the northern Konkan uplands. These groups controlled key passes linking the western coast with the Deccan interior, including the Tal pass near modern-day Jawhar. Though lacking written records, oral traditions point to a figure named Paupera, later identified as Jayabha Mukne, as the founder of the ruling line.

According to local accounts, Paupera resided near the Tal pass, and during a pilgrimage to the dargah of Sadruddin Chishti at Pimpri, received a prophetic blessing from five holy men. Following this, he travelled through Peint, Dharampur, and Kathiawar, gathering followers. On returning to the region, he negotiated with a Varli chief for land "equal to the area covered by a bullock hide." The hide was cut into fine strips and used to encircle a substantial tract. In exchange, the Varli chief was granted Gambhirgad (now in Dahanu taluka), while Paupera established his seat at Jawhar.

The formal foundation of the state is dated to 6 June 1306, when Jayabha Mukne seized the fort at Jawhar. His son, Dulbarrao, expanded the domain significantly, acquiring control over 22 forts across parts of the present-day Thane and Nashik districts.

Notably, in 1343, the Delhi Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq recognised these conquests, conferring upon Dulbarrao the title of Raja and the name Nim Shah. From this date, the state adopted a distinct calendar, which is termed the Jawhar era; this was used in administrative and revenue records for over six centuries.

In the subsequent period, Jawhar maintained nominal allegiance to regional powers, including the Gujarat Sultanate and the Bahmani Sultanate, though there is little evidence of direct interference in its internal affairs. The Mukne chiefs retained control of their territory throughout, administering from their fortified seat in Jawhar.

Medieval Period

During the early 15th century, the Gujarat Sultanate, also referred to as the Sultanate of Guzerat, rose to prominence primarily within the present-day state of Gujarat. Throughout its existence, the Sultanate actively fought against Portuguese expansion, engaging in several battles to resist Portuguese territorial encroachments and safeguard its own interests. Muzaffar Shah I, who became the Tughlaq governor of Gujarat after his father's demise in 1371, founded the kingdom. Delhi sultanates’ influence through their representatives continued until Timur Sacked Delhi in 1398.

After Timur's invasion weakened the Delhi Sultanate significantly. It prompted Muzaffar Shah I to declare independence in 1394 and formally establish an independent Sultanate. Under the reign of Mahmud Begada, the sixth king of the Sultanate (1459-1511), the prosperity of the Sultanate reached its peak. As these powers vied for their influence in the district, places such as Bassein (present town of Vasai) became a part of their exploits.

Portuguese

In the early 16th century, the Portuguese Armadas, emboldened by Vasco da Gama's discovery of the Cape route, ventured to India. In 1498, they made landfall at Calicut (present Kozhikode), marking the beginning of a new chapter in history.

For years to come, the Portuguese, through diplomatic maneuvers, worked to solidify their foothold in the north and south Konkan, attracted by its bustling coastal ports. In 1510, they seized Velha Goa from the Adil Shahi dynasty of Bijapur and established it as their capital.

They expanded their reach further. Notably, in 1509, Francisco de Almeida's expedition led to the discovery of the coast of Vasai, which became a pivotal moment that would shape the course of the district’s history. The capture of Vasai was preceded by a period of conflict. In 1530, hostilities erupted between the Portuguese and the forces of Alishah of Gujarat. According to the Thana District Gazetteer (1882), Captain António da Sylveira led a Portuguese military campaign against Bassein, where Alishah had assembled an estimated force of 8,500 men. A confrontation followed, resulting in a decisive Portuguese victory.

Following the conflict, Bassein was plundered and destroyed by the Portuguese. The town, which had been a flourishing settlement, suffered extensive damage and loss of life. In 1531, António de Saldanha is reported to have again set fire to Bassein, in what appears to have been a punitive measure aimed at deterring future opposition to Portuguese authority.

Treaty of Bassein / Vasai, 1534

In 1534, a significant political development unfolded in the district with the signing of the Treaty of Bassein, which resulted in the formal transfer of Vasai and its surrounding territories to Portuguese control. At the time, Bahadur Shah, the tenth Sultan of Gujarat, was engaged in conflict on multiple fronts: facing threats from the Rajputs, the advancing Mughal Empire, and the Portuguese.

In an effort to consolidate his position, Bahadur Shah sought an alliance with Nuno da Cunha, the then-Governor of Portuguese India. A treaty was negotiated and dispatched through the Sultan’s chief officer, Shah Khawjeh (referred to in Portuguese records as Xacoes).

Under the terms of the treaty, the port of Bassein, its dependencies, and associated revenues by land and sea, along with the seven islands of Bombay, were ceded to the Portuguese. The agreement also required that all ships of the Sultanate sailing toward the Red Sea obtain a cartaz (a naval pass) from the Portuguese authorities stationed at Bassein.

Vasai Fort

The Fort of Vasai, historically known as Fort Bassein or Bacaim Fort, was constructed by the Portuguese in the 16th century following their consolidation of control in the region. It remains one of the most prominent surviving traces of their presence on the Konkan coast. Notably, the fort is believed to have once enclosed an entire fortified town within its walls.

Its defensive structure included ten bastions, nine of which were identified by names such as Cavalheiro, Nossa Senhora dos Remédios, Reis Magos Santiago, São Gonçalo, Madre de Deus, São João, Elefante, São Pedro, São Paulo, and São Sebastião: the latter also referred to as "Porta Pia" or the Pious Gate of Baçaim. A Portuguese atlas from the period includes detailed maps of the fort layout as it stood during the governorship of Nuno da Cunha.

The fort served both as a military outpost and a commercial center, reflecting Portuguese maritime interests in the Arabian Sea. During the height of Portuguese influence, Vasai earned the designation "Court of the North", becoming a resort town frequented by nobility and affluent merchants from Portuguese India. The town gained a reputation for its unique architecture, churches, and palatial residences. It also functioned as the administrative headquarters for the northern province, considered among the most economically productive regions under Portuguese rule. The fort maintained its status as a thriving center of commerce and culture during this time and throughout the centuries to come.

Spread of Christianity

The establishment of the Portuguese in the region facilitated the spread of Christianity and the religious transformations that occurred as a result of Portuguese influence. Efforts of missionaries, such as the Franciscans and Jesuits, to convert the local population, accompanied by the destruction and conversion of Hindu temples into churches, the establishment of orphanages, and the gradual acquisition of land for church purposes in Vasai. The conversion effort in the district was largely attributed to the influential Franciscan missionary Francis Antonio de Porto.

According to the Thane District Gazetteer (1882), he oversaw the destruction of Hindu Mandirs, rebuilding them as churches, and persuaded many to convert to Christianity. Additionally, he established orphanages, which during times of war and famine, were populated with abandoned children, thus contributing to the formation of a native priestly class.

After 1548, with the assistance of St. Francis Xavier, the Jesuits gained a strong presence in Vasai and Bandra. Like other nearby districts, through their effective preaching, they successfully converted many individuals of the high caste to Christianity. Baptism ceremonies were conducted with great pomp and ceremony, with some accounts highlighting as many as 9,400 converts being baptized in Bassein Cathedral in one year (1538) alone.

Following the establishment of Goa as an Archbishopric and the introduction of the Inquisition in 1530, efforts to suppress Hindu worship and promote Christianity intensified. Previous allowances for the free exercise of Hinduism were revoked during the reign of Philip II of Portugal (1580-1598), leading to a widespread nominal conversion of the population in Vasai and Salsette at large. Subsequently, approximately half of Salsette's land gradually became church property through grants.

The Jesuit College in Bandra (Mumbai) served as the headquarters of the order, while most of the churches and religious houses in Salsette were administered by the Franciscans. By the end of the 16th century or shortly thereafter, Vasai housed establishments of all the major religious orders, and it was during this time that the College was established. In 1547, they built Igrja de Santo António and the Igreja Matriz de São José, and in 1549, the Jesuits built the Igreja do Sagrado Coração de Jesus.

Vasai Plague

In 1618, the district faced a series of calamities. A plague struck first, followed by a devastating cyclone on 15 May which caused extensive damage to boats, homes, and coconut trees, while also bringing brackish seawater inland. Many churches and convents suffered, with roofs torn off and structures nearly beyond repair. The cyclone was followed by a severe drought, leading to famine-like conditions. Some accounts indicate that desperate parents even resorted to selling their children into slavery to some brokers to avoid starvation.

Decline of Portuguese Control

By the late 17th century, the Portuguese stronghold in the region began to weaken. Portuguese authority declined following the transfer of Bombay Island to the British in 1665, as part of the dowry of Catherine of Braganza to Charles II of England. This transfer marked a turning point, giving the East India Company a strategic foothold.

In 1674, approximately 600 Arab pirates from Muscat (Oman) landed on the Konkan coast. Although the local garrison remained within the fortified walls, the pirates looted churches situated outside the fort and inflicted violence on the civilian population.

Adding to the strain, in 1676, Shivaji’s forces approached Saiwan (modern Dahanu taluka), challenging Portuguese control in the northern Konkan.

The Maratha Conquest of Vasai

In the 18th century, Vasai Fort became a contested site during the Maratha expansion. Led by Chimaji Appa, the brother of Peshwa Baji Rao I, the Marathas launched a campaign against Portuguese territories in 1737. After intense fighting, the fort was captured in 1739 during the Battle of Vasai.

This marked the beginning of a wider collapse of Portuguese power in the region. Between 1737 and 1743, most Portuguese possessions in and around Vasai fell to the Marathas. The conflict led to the destruction of numerous churches, and as recorded in the Thane district Gazetteer (1882), a large number of Christians were said to have been reconverted to Hinduism.

In the treaty that followed the cession of Vasai, the Portuguese government successfully negotiated to retain five churches for the remaining Christian population under their spiritual care:

- Three within the fortified town of Vasai,

- One in the surrounding district, and

- One on the island of Salsette.

The agreement allowed the Marathas to assume full control over former Portuguese territories while providing limited religious and institutional concessions to the Portuguese. It also led to the departure of most Portuguese monks, clergy, and European families.

Marathas and the Jawhars

In the late 17th century Maratha forces made their way into the Jawhar kingdom. The successive king, Raja Vikramshah I had an initial alliance with Shivaji. In 1664 they even at Shirpamal (near Jawahar city) during Shivaji's expedition to Surat, where they jointly participated in the plunder of the city. However, their relationship soured soon after, leading to a falling-out between the two parties.

Following this rift, the Marathas gradually increased their influence over the Mukne rulers, tightening their grip through annexations of districts and imposing escalating taxes, levies, and fines. The Marathas took control of the state in multiple instances, notably in 1742, 1758, and 1761. But each time they relinquished the control back to the Mukne family under the condition of territorial concessions and increased tribute payments.

By 1782, the Raja was left with a land-locked territory in the hills, which generated a modest annual revenue. Despite retaining nominal authority, the Mukne rulers were significantly constrained by Maratha dominance, marking a period of diminishing autonomy for the state.

Colonial Period

Colonial Administrative changes

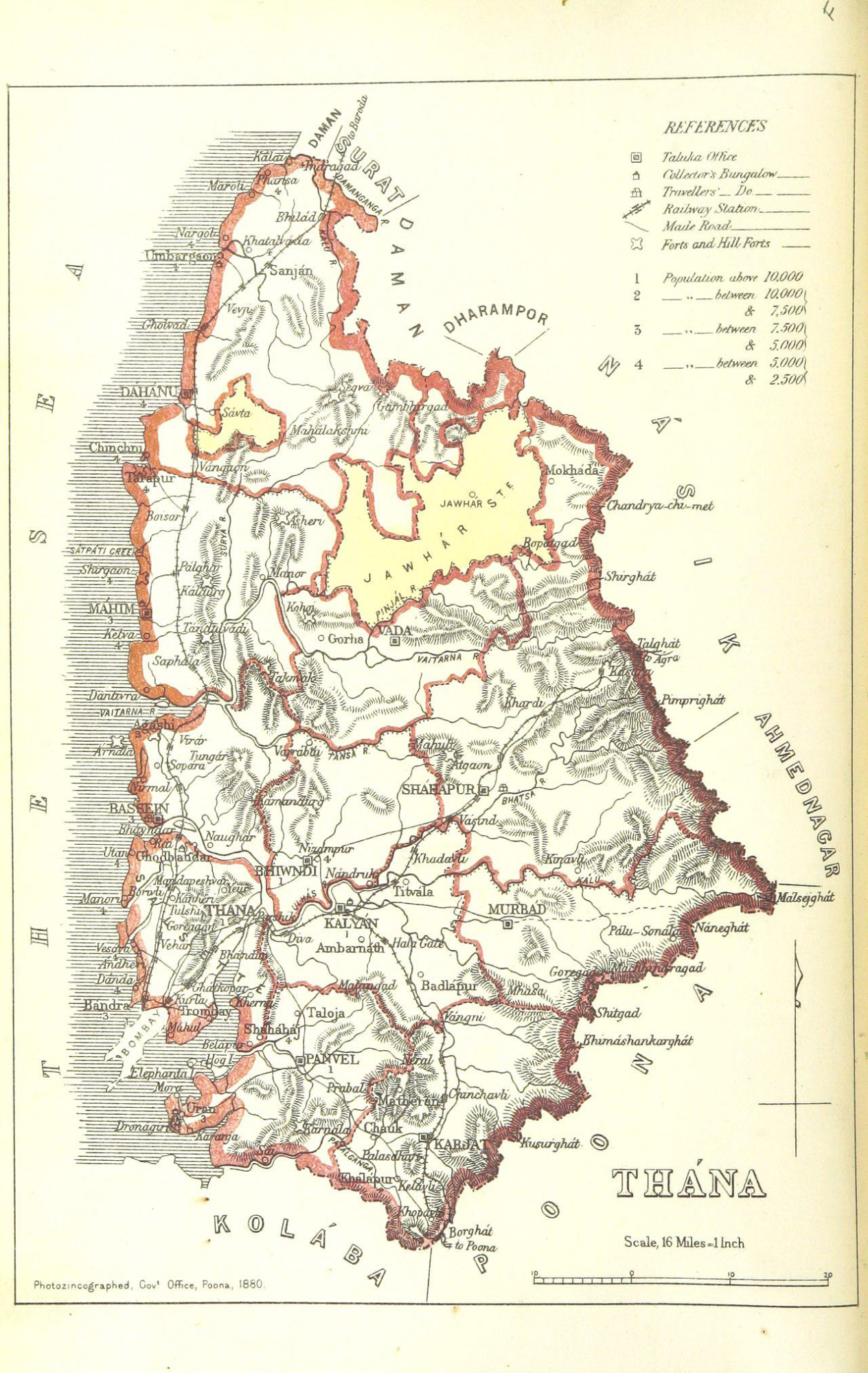

In 1560, the Portuguese undertook an administrative restructuring to manage their territories effectively along the Thana coast. When the Portuguese gained the whole coast from Daman to Kanja, they divided their Thana territories into two: Daman ( UT of Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu) and Bassein (Vasai in Palghar district). Under Daman were four districts: Sanjan, Dahanu, Tarapur, and Mahim; under Bassein were seven districts: Asheri, Manor, Bassein Salsette, Bombay, Belapur or Shahbag, and Karanja.

Under British rule, there was a further restructuring of the administrative setup. Palghar was separated from Daman and incorporated into the Thane district. This inclusion extended the northern territorial boundary of Thane district, reflecting a shift in administrative boundaries and governance during the British colonial period.

Jawhars Under Colonial rule

The third Anglo-Maratha war (1818) resulted in the onset of British rule in the region. Under the British Jawhars became one of the Princely states. The progress however during this period appears to have been slow due to the meager revenue receipts and disorganized administration. The territory of Jawhar state was surrounded by the Thane district and fell under the jurisdiction of the Thane colonial administrative agency during the British colonial period.

It wasn't until the reign of Patangshah IV that significant improvements began to take place. Patangshah IV, known for his enlightened and well-educated leadership, initiated a series of reforms aimed at enhancing governance, infrastructure, and social services. His efforts led to the construction of roads, schools, and dispensaries, marking a notable improvement in living conditions by the time of his death in 1905.

The reigns of Patangshah's successors, Krishnashah IV and Vikramshah V, also witnessed steady progress and development. Vikramshah V, in particular, focused on enhancing the agricultural sector by constructing wells, securing land rights, and upgrading the state's infrastructure. He played a significant role in supporting the war effort during the Great War, earning recognition through a 9-gun salute for his services. However, his untimely demise in 1926 resulted in a ten-year regency for his son, Yeshwantrao Patangshah V.

Yeshwantrao Patangshah V, having received an exceptional education, assumed full ruling powers in 1938. He continued the developmental momentum initiated during the regency period, fostering growth across various industries such as chemical, paper, textile, dyeing, printing, liquor, and starch. Moreover, the state under his leadership provided free primary schooling and medical relief, established middle and high schools, a central library, a museum, a hospital, a maternity home, and touring dispensaries for rural areas. Yeshwantrao's reign was characterized by a commitment to progress and welfare, further solidifying the state's path towards modernization and prosperity.

World War II onwards

Amidst the tumult of the Second World War, Raja Yeshwantrao Patangshah volunteered for duty. He joined the Royal Indian Air Force and fought for four years on behalf of the Allied powers.

In the wake of the war's end and the departure of the British, Yeshwantrao Patangshah V made a significant decision. Embracing the title of Maharaja, he depicted a transition in leadership and governance. This momentous step culminated in the merger of his state into the Bombay Presidency, marking a pivotal chapter in the region's history.

To commemorate his ascension to the title of Maharaja and to recognise the contributions of those who served during his reign, Maharaja Yeshwantrao Patangshah V established the prestigious Maharaja Medal in 1947. This medal, awarded in a single class, honored the dedication and loyalty of individuals who had supported the state under his rule.

Transitioning from princely rule to political leadership, he became a member of both the national parliament and the state assembly, championing the interests of his people on a broader stage. After a lifetime of service and leadership, Maharaja Yeshwantrao Patangshah V passed away in 1978, leaving behind a legacy of dedication and progress. He was succeeded by his son, Digvijaysinhrao, who, unfortunately, also departed from this world in 1992. With the responsibility passed on to his grandson, Mahendrasinhrao, the lineage of the Jawhar rulers continued.

Environmental Changes in Dahanu

Dahanu, another coastal town within the district, was once a village and has since developed into a town. It is popularly believed that the name "Dahanu Gaon" is derived from the term "Dhenu Gram," signifying the village of cows. It was reputed for its abundant livestock, particularly cows, which were extensively owned by the local people.

The region has experienced significant environmental changes for a very long time. It is recorded that in 1882, changes in Dahanu were due to two main factors: sea encroachments and land reclamation. Over centuries, these forces had altered the coastal landscape significantly. Since 1724, the gradual advancement of the sea has resulted in the submergence of villages and the erosion of an old government house.

To mitigate this, perhaps sea encroachments, where the sea gradually advanced onto the land, were countered by land reclamation. These reclamations, often conducted during periods of strong government, have been ongoing for centuries. They have transformed vast expanses of salt marshes into fertile arable land. Notable instances of sea encroachments include areas like Utan, Dongri in Salsette, along the Vasai coast, and further north at Chikhli, Gholvad, Badlapur, Chinchani, and Dahanu. Particularly striking examples are seen in Dahanu, where the sea advanced approximately 1,500 feet, and at the mouth of the Vaitarna river, where four villages have been submerged since 1724.

It is argued that land reclamations were typically carried out in small plots. Initially, these plots produced salt rice, but over time, they were freed from their saline conditions and transformed into fertile rice-growing areas.

Some larger-scale efforts have been made to control sea encroachments, including the construction of embankments. Examples include embankments to the east of Dahanu, near Tarapur in Mahim, at Rai Murdha and Majivri in Salsette, along the Kalyan river, and in parts of Panvel. The embankments serve to protect villages and rice fields from tidal inundation, with the Dahanu embankment, in particular, being crucial in preventing flooding in the town.

Sugar Making: Traditional and Colonial

In the district, Vasai in particular, was prominent for local raw sugar making. It was a significant economic activity in the region, involving multiple communities. It is recorded that raw sugar production in the Bassein sub-division was primarily carried out by Prabholkaris, Malis, Native Christians, and Samvedi Brahmins. The sugar-making season typically spanned from February to June. During this period, women and children assisted by transporting sugarcane from the gardens to the sugar mill or gharri. The sugar-making process involved the use of several tools and appliances. These included: the vita or sickle, used for chopping the roots of the cane.

Perhaps the British government, realising the local potential, aimed to tap into it and hoped to foster economic growth. Because around the early 1800s, the British government put a concerted effort into promoting Mauritius cane cultivation to increase the manufacturing of raw sugar.

According to the Thane District Gazetteer (1882), in the 1820s and 1830s, initiatives led by individuals like Mr. Lingard aimed to harness the fertile lands of Vasai for promoting Mauritius sugarcane cultivation and sugar production. For this Government granted him land and financial assistance provided However, his sudden demise in 1832 disrupted the project, leaving debts and the estate in disarray. The tenure was granted to Narayan Krishna. However, the challenges persisted in achieving sustainable sugar production. Investment, technical expertise, and market access emerged as crucial factors in overcoming the hurdles faced by aspiring sugar producers. In 1837, Messrs. McGregor Brownrigg & Co. were granted a trial of the estate for three months, which proved satisfactory. As a result, they requested a long lease.

In 1841, they were granted a perpetual lease for approximately 115 acres near the travelers' bungalow on the esplanade in Vasai. The lease began in 1839, initially rent-free for forty years, after which they were to pay some annual rent. The lessees agreed to cultivate sugarcane, although this commitment was binding for only seven years, with the expectation that sugar production would become firmly established by then. However, this hope was not realized.

In 1843, Messrs. reported that sugarcane cultivation was unprofitable due to poor soil quality and lack of shelter. Consequently, they opted to level the ground, dig wells, and cultivate other types of superior produce. In 1848, they sold the estate to Mr. Joseph, who later sold it to one Dossabhoy Jahangir in 1859. Subsequently, Mr. Jahangir sold the estate to Mr. J. H. Littlewood in the same year.

Cocoa-Palm Farming in Dahanu

Although not very prevalent at present, in Dahanu during the 1800s, cocoa-palm farming is said to have flourished. In 1882, Dahanu village was one of the primary cocoa-palm gardens. During the period land acre rate was increased and set at 12 annas (6 paisa). This adjustment resulted in an increase in payment from £102 to £125. Perhaps a higher payment requirement is indicative of either increased demand for cocoa-palm products or improved conditions for cultivation, leading to higher land values. This adjustment may imply that cocoa-palm farming likely thrived or was seen as more profitable during that period in Dahanu.

1875 Cholera Outbreak

In 1875, cholera raged in the district, likely due to a lack of healthcare infrastructure and medical resources. According to the Thane District Gazetteer (1882), the cholera outbreak of 1875 was particularly severe in Palghar district, with the first cases reported in April in Kalyan and Shahapur, followed by its spread to other areas like Bhiwandi, Karjat, Bassein, Mahim, and Dahanu in May. Out of 386 cases reported, 182 resulted in fatalities. Further, it mentions that:

“the available details of the Dahanu outbreak show that the disease appeared on the 28th of May at the village of Nargol, on the 1st of June at Palgadu, on the 4th of June at Gholvad on the Baroda railway, and on the 6th at Urabargaon. It continued till the 23rd of June, but only nine villages suffered. The outbreak was fiercest at Gholvad, where the villagers are reported to have been panic-struck and to have died in the streets, in some cases within half an hour after seizure. The disease was mostly confined to Mochis, Dublass, Varlis, Kamlis, Maugelas, and Dheds, who are generally poor, badly fed, much given to liquor-drinking, and whose habits are dirty. No accurate records of the seizure and deaths in this outbreak are available.”

Struggle for Independence

The present-day district of Palghar, though peripheral to the main centres of nationalist mobilisation, played a discernible role in the broader movement for Indian independence. By the 1930s, the influence of the Indian National Congress had begun to make itself felt in the coastal villages of the region, particularly in the context of the Civil Disobedience campaigns. At Saatpati, a fishing settlement north of Palghar town, the boycott of foreign goods was enforced with notable rigour. During this period, local volunteers actively discouraged the use of imported cloth and merchandise, marking the village as a focal point of Satyagraha-inspired activity.

A more serious confrontation with colonial authority occurred in August 1942, during the height of the Quit India movement. On this occasion, demonstrations held across the region in response to the All-India Congress call for immediate British withdrawal culminated in police firing at Palghar. Five individuals lost their lives: Kashinath Hari Pagdhare of Saatpati, Govind Ganesh Thakur of Nandgaon, Ramachandra Bhimashankar Tiwari of Palghar, Ramchandra Mahadev Churi of Murabe, and Sukur Govind More of Shirgaon. Their deaths are among the most significant acts of sacrifice recorded in the district during the freedom struggle.

In later years, a memorial square (Panch Batti) was established in Palghar town to commemorate their contribution. The site remains the principal locus of annual remembrance in the district, with 14 August observed locally as Martyrs' Day.

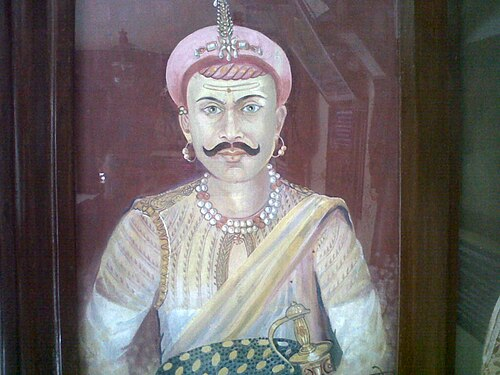

Portraiture and the Case of Ramchandra Mahadev Churi

Despite his recognised place among the martyrs of 1942, no photographic or painted record of Ramchandra Mahadev Churi was known to exist for several decades following independence. During commemorative preparations in 2020, his absence from visual displays became the subject of community concern.

Efforts were initiated in Murabe village to reconstruct Churi’s likeness. Oral testimonies from elders were collected and compared against the features of his surviving descendants. With the assistance of a local schoolteacher and reference photographs of family members, a portrait was rendered in oil and endorsed by the village panchayat. The image, subsequently submitted to the state government for authentication, now forms part of the official tableau of martyrs maintained at Panch Batti.

Post-Independence

After Independence in 1947, the region now comprising Palghar district continued to be administered as part of Thane district within the Bombay State. In 1956, the States Reorganisation Act was enacted to redraw state boundaries along linguistic lines. Subsequently, in 1960, the bilingual Bombay State was bifurcated into Maharashtra and Gujarat. Thane district, including the present-day Palghar region, became part of the newly formed state of Maharashtra.

Over the following decades, Thane district witnessed rapid urbanisation and population growth, emerging as one of the most densely populated districts in the country. The vast geographical area and increasing administrative demands led to a proposal for bifurcation. In August 2014, the Government of Maharashtra officially notified the formation of Palghar as the 36th district of the state. The new district was created by separating eight talukas, namely, Vasai, Palghar, Dahanu, Talasari, Vikramgad, Jawhar, Mokhada, and Wada, from the northern and western areas of Thane. The town of Palghar was designated as the district headquarters.

Agricultural Developments

Agriculture remained a key economic activity in the region during the post-Independence period. Certain areas became associated with specific crops due to local agro-climatic conditions and cultivation practices.

Chikoo Cultivation in Dahanu

Dahanu taluka, particularly the villages of Bordi and Gholvad, became known for chikoo (sapodilla) cultivation. Notably, the Gholvad variety was granted a Geographical Indication (GI) tag. Farmers in the region expanded cultivation and engaged in small-scale processing of the fruit into products such as sweets, beverages, and pickles. The crop continues to be an important source of income for cultivators in this region.

Wada Kolam Rice in Wada

Wada taluka is associated with the cultivation of Wada Kolam, a traditional rice variety also referred to as Zini or Jhini. The variety is noted for its small grain size, aroma, and soft texture. It is grown in a number of villages in the taluka, primarily through low-input or organic farming methods. In 2021, Wada Kolam received a GI tag, in recognition of its geographical and varietal distinctiveness. It is sold in regional markets and has a steady consumer base.

Industrial and Technological Infrastructure

The district also witnessed industrial expansion in the post-Independence period, with one of the most significant developments being the establishment of the Tarapur Atomic Power Station.Located near Boisar, this facility was the first commercial nuclear power plant in India and remains one of the most significant industrial establishments in the district. It is operated by the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited (NPCIL).

The initial phase of the project involved the installation of two Boiling Water Reactor (BWR) units, constructed with technical assistance from General Electric, United States. These units were brought online as part of India’s early efforts to establish nuclear power capacity. In subsequent years, two Pressurised Heavy Water Reactor (PHWR) units were added to increase output and diversify reactor design.

Sources

A Ghosh ed. 1956. Indian Archaeology 1955-56 – A Review. ASI.https://www.asiaurangabadcircle.com/assets/f…

Ashutosh Bijoor. 2013. Nalasopara – Buddhist Stupa & Chakreshwar Mahadev Temple – a cycling expedition.http://bijoor.me/2013/12/28/cycling-to-nalas…

Benita Chacko. 2016. Vasai Fort: From a prized asset to the ‘city of ruins. The Indian Express.https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/mum…

Blog Posts Referred: Kshatriya Thakor History And Inheritance: Jawahar State, Sahasa. Dahanu Gholvad Chikoo, Maharashtra, Tīrtha Yātra. Chakreśvar Mahādev Mandir (Nalasopara, Thane),Buddha Dharma Education Association, Colonial Voyage. Cloister of the Franciscan Igreja de Santo António. Vasai, Bassein, Baçaim, N.S Energy. Tarapur Atomic Power Station, Maharashtra, Travel India: History of Vasai.

Da Cunha, J. Gerson. 1993. Notes on the History and Antiquities of Chaul and Bassein. Asian Educational Services.

Dipanjan Roy Chaudhury. 2019. Russia supplies fuel to India’s oldest nuclear power plant. Economic Times.https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industr…

F.E Pargiter. 1922, reprint 1972. Ancient Indian Historical Tradition, Motilal Banarasidass, Delhi.

Gazetteer Department. 1882. Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency. Government Central Press.

GD House. 2018. Nala Sopara and Vasai. Medium.https://medium.com/@gdhouse/nala-sopara-vasa…

James M. Campbell. 1882. Gazetteer Of Bombay Presidency Thana District Vol 13. Government Central Press.

Kurush Dalal. 2019. Chinchani & India’s First Arab Governor. Peepul Tree.https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindi…

Kuzhippalli Skaria Mathew. 1986. Portuguese and the Sultanate of Gujarat, 1500–1573. Mittal Publications.

Nina Martyris. 2001. When Emperor Ashoka rocked Nalla Sopara. Times of India.https://web.archive.org/web/20120418140428/h…

PTI. 2021. Maharashtra: Palghar’s famed Wada Kolam rice gets GI tag. Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/toirepor…

Sandhya Nair. 2012. Palghar: 80 years on, 'faceless' martyr gets a portrait. Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mum…

Sandhya Nair. 2017. Dahanu-Gholvad chikoo gets geographical tag. Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mum…

Suraj Pandit. 2017. The Legendary Sopara. Peepul Tree.https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindi…

Last updated on 18 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.