Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Stone Age Settlements at Nakvi

- Political Powers & Dynastic Traditions

- Rashtrakuta Presence and Jain Heritage of Jintur

- The Yadavas and the Rise of Hemadpanthi Architecture

- Charthana and the Mysterious Ruler Charuddata

- Sant Janabai

- Medieval Period

- Delhi Sultanate

- Rise of the Bahmani Sultanate

- The Contest Over Pathri and the Struggles for Berar

- The Battle of Sonpeth (1597)

- Parbhani Under the Mughals

- Marathas

- The Do-Amli System in Parbhani

- British Involvement and Integration into Hyderabad

- Nizams Under the British Paramountancy

- The First War of Independence (1857)

- Commerce

- Post-Independence Era

- Reforms and Industrial Development

- Sources

PARBHANI

History

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Parbhani district is situated in the Marathwada region of Maharashtra and bears a rich historical and cultural legacy. It occupies a significant position in the broader narrative of the Deccan, with archaeological evidence indicating continuous human habitation since prehistoric times. In historical tradition, the district is identified with the ancient Vidarbha kingdom. In later centuries, it formed part of the Berar province until 1853, when Berar came under British control though nominally ruled by the Nizam of Hyderabad. Parbhani remained a district of Hyderabad State until its accession to the Indian Union in 1948.

In addition to its historical associations, Parbhani is also notable for its religious and cultural heritage. The town of Pathri is traditionally regarded as the birthplace of Sai Baba, while Selu is linked with his guru, reflecting the region’s importance in the saint’s early life. The district also contains significant sites such as the Turabul Haq Dargah in Parbhani city, a prominent Sufi shrine, and the Nemgiri caves, associated with early Jain monastic traditions.The district is also associated in local tradition with Valya Koli, a figure whom some accounts identify with the sage Valmiki, and with Sant Janabai, a revered figure in the Bhakti movement.

Etymology

The name Parbhani is generally held to be a later form of Prabhavati Nagari, an older designation believed to have referred to a settlement centred around a Mandir dedicated to the Devi Prabhavati. She, in local tradition, is understood to represent combined aspects of Lakshmi and Parvati, and the name itself appears to derive from this association.

Ancient Period

The region now forming Parbhani district has, over time, fallen under the influence of different political and cultural powers. Although much of its early history remains unknown, archaeological remains and scattered references in literature offer some insights into the region’s past. These traces are best understood in the context of the wider Deccan and Marathwada regions, with which Parbhani has long shared geographic, political, and cultural ties.

Stone Age Settlements at Nakvi

One of the earliest glimpses into Parbhani’s history comes from the area surrounding Nakvi, particularly the village of Pandhari Tarf Navki (formerly Kumbhar Pandhari) in Purna taluka. Archaeological surface finds from the site include red and black ware pottery, terracotta beads, and miniature wheels which are, notably, objects that are typically dated to the early historic period.

Alongside these, older implements have also been recovered, including stone axes, sickles, and knife blades attributed to the Early Stone Age (approximately 5,00,000 to 10,000 BCE). These tools, in many ways, provide evidence of some of the earliest human presence in this part of the Deccan.

Political Powers & Dynastic Traditions

The earliest indications of political authority in the region now forming Parbhani district appear during the Mauryan period in the 3rd century BCE. While no Mauryan inscriptions have yet been found in Parbhani itself, a small number of references from nearby areas suggest the district may have fallen within the wider sphere of Mauryan influence.

Notably, an inscription issued by a dharmamahāmātra under Ashoka, found at Deotek in Chandrapur district, indicates the presence of Mauryan administration in the nearby eastern Vidarbha region. Of greater relevance to Parbhani are Ashoka’s fifth and thirteenth rock edicts, which mention the Rashtrikas, Petenikas, and Bhojas—groups later associated by scholars with western Maharashtra, Paithan (in present-day Sambhaji Nagar), and the Vidarbha region respectively. These were likely local ruling houses, some of whom possibly acknowledged or served as chieftains under the Mauryan authority. Parbhani’s position, between Paithan and the Godavari basin, in many ways, places it within the zone connected to these groups. It is therefore likely that Mauryan control in the area was indirect, exercised through local chiefs or subordinate lineages.

After the death of Ashoka, the Mauryan Empire began to disintegrate. In the absence of strong central control, many regional powers began to reassert themselves across the Deccan. Among the most prominent successors in northern India were the Shungas, a dynasty that rose to power in the 2nd century BCE, shortly after the Mauryas.

Although there are no inscriptions from this time in Parbhani, a later literary work offers a glimpse—however stylised—into the political tensions of the period. Malavikagnimitram, a Sanskrit play written by the classical poet Kalidasa, includes a subplot about a military conflict between the Shunga prince Agnimitra and the Raja of Vidarbha, a region that borders the present-day Parbhani district. The story ends with Vidarbha being divided between two brothers—one continuing to rule, the other supported by the Shungas.

While the play was composed centuries after the events it describes and is primarily a courtly drama, historians read its subplot as a reflection of the shifting balance of power in the Deccan after Mauryan rule. The same episode is mentioned in the Yavatmal district Gazetteer (1908), which records that Agnimitra “found it necessary to make war on his neighbour, the Raja of Vidarbha,” and that the Wardha River was fixed as the boundary between their territories.

If this account holds some truth, then Parbhani—along with Amravati, Akola, and Nanded—likely fell within the western half of this divided region, ruled by the original Vidarbha lineage or under local control allied to it.

After the Mauryas, a dynasty called the Satavahanas came to power in the Deccan. They ruled large parts of what is now Maharashtra, Telangana, and Andhra Pradesh for about four centuries. Their capital was at Paithan (then known as Pratishthana), which is just west of present-day Parbhani.

Although no Satavahana inscriptions have been found in Parbhani district itself yet, evidence of their rule has surfaced in nearby areas. Coins and pottery linked to the Satavahanas have been unearthed in Dharashiv, Jalna, and other parts of the present-day Marathwada regions. These finds suggest that the Marathwada region was, very much, part of the broader political and economic zone under their influence.

Parbhani is located in the midst of Paithan and Ter (in Dharashiv), both of which were important towns during this time. Paithan was a political and religious centre, and Ter was a busy trading town that connected to ports on the coast. Goods like cloth, beads, and metals moved along this route. Because of its position between these two towns, Parbhani was likely part of this trade network.

After the Satavahanas lost power, another dynasty called the Vakatakas became important in the Deccan. They ruled large parts of central India, especially in the present-day Vidarbha region, which borders the eastern side of today’s Parbhani district.

The Vakataka dynasty had two main branches. One of them ruled from a city called Vatsagulma, which is believed to have been in or near present-day Washim, which lies just northeast of Parbhani. This branch is often referred to as the Vatsagulma branch of the Vakatakas. So far, no inscriptions or artefacts from the Vakataka period have been found in Parbhani itself. But since Washim was their capital, and Parbhani lies close to it, hence, it is very likely that this area was included in their territory.

Rashtrakuta Presence and Jain Heritage of Jintur

Control over the region shifted again in subsequent centuries. The Kalachuris briefly extended their authority into parts of the Deccan, followed by the Chalukyas of Badami, who expanded southward from Karnataka in the 6th century CE. By the 8th century CE, the Rashtrakutas had emerged as a major power in the Deccan. Their control extended across large parts of Maharashtra, including what is now Parbhani district.

One of the most lasting legacies of the Rashtrakutas in this area is their support for Jain religious traditions. They were known patrons of Jainism, and many Jain sites in Parbhani, especially in Jintur taluka, are believed to have developed during or shortly after their rule. According to local tradition, Jintur was once called Jainpur, and is associated with Amoghavarsha I, a Rashtrakuta ruler who is remembered as a supporter of Jainism.

Many sites in the district appear to belong to this phase of history. Among the sites of note are the Nemgiri Caves, located near Jintur which have been carved directly into the hillside and house images of Jain Tirthankaras that date back to this period.

Other traces of early Jain activity can be found at Navagadh, where sculptural fragments and remains of old shrines suggest the presence of religious communities active during the same period.

Today, that legacy continues at the Shri Digambar Jain Atishaya Kshetra in Jintur. The temple complex is maintained by Jain trusts that see themselves as part of a long-standing tradition — one likely shaped, in its early centuries, during the Rashtrakuta period.

The Yadavas and the Rise of Hemadpanthi Architecture

By the 12th century, political control over the region had shifted again, this time to the Yadava dynasty, whose capital at Devagiri (present-day Daulatabad which lies in the nearby Sambhaji Nagar district) became a major centre of power in the Deccan. Under their rule, a distinctive style of construction began to appear across the region, known today as Hemadpanthi architecture.

This style is marked by the use of black basalt, cut into large blocks and assembled without mortar. Notably, several structures in Parbhani district reflect this technique, offering some of the earliest visible evidence of built architecture tied to the dynasty in the area. There is a stepwell at Arvi, which with its carefully fitted stone and geometric layout, stands as a notable example of this building tradition.

Several mandirs in the district also belong to this period. At Pokharni, the Mudgaleshwar Mandir, located near the Godavari River, draws attention not only for its architecture but also for its unique setting. During the monsoon, the rising river partially submerges the temple, creating a dramatic seasonal change that continues to attract yatris, especially during Mahashivratri. Another example is the Gupteshwar Mandir at Dharasur, which also follows Hemadpanthi conventions. Though modest in size, the presence of these mandirs point to a time when the region saw steady temple-building activity under the Yadava period.

Charthana and the Mysterious Ruler Charuddata

While major dynasties like the Rashtrakutas and Yadavas provide a broad political framework, not all parts of Parbhani’s past fit neatly into these larger narratives. Local traditions preserve the memory of rulers and settlements whose stories survive outside inscriptional records.

One such story in the present-day district is of Charthana, a village in the district whose name is believed to derive from a king called Charudatta. According to oral tradition, Charudatta ruled the area in the distant past, though his identity remains largely unknown.

Still, there are signs that Charthana was an important settlement in the earlier times. Scattered around the village are the remains of old stone mandirs, many now in a damaged or fragmentary state. These structures show features typical of Hemadpanthi architecture—such as the use of large black basalt blocks, fitted without mortar—and are believed by scholars to date to the Yadava period (12th–14th century CE).

Sant Janabai

Sant Janabai made a profound contribution to the Warkari tradition with her abhangs (devotional poems) that express a deep, personal, and egalitarian devotion to Vithoba. She was born in the 13th century in the village of Gangakhed in Parbhani district.

She was a dasi (maid-servant) in the household of the sant Namdev in Pandharpur, which became her karmabhoomi. She considered Namdev her Guru. Her poetry is a unique and powerful voice for women and those who are oppressed. She wrote for Bhagwan Vithoba as her personal friend, helper, and companion, who assisted her with her daily household chores, such as grinding grain. Her abhangs are a testament to the fact that devotion and sainthood are not dependent on caste, gender, or social status.

Medieval Period

Delhi Sultanate

Towards the end of the 13th century, a remarkable shift took place in the political history of the Deccan region as the Delhi Sultanate began marching south towards the region. In 1294, Alauddin Khilji, then a general and the son-in-law of the Delhi Sultan, raided Devagiri, the capital of the Yadava dynasty. Though the raid did not lead to permanent annexation, it exposed the weakness of the Yadavas and marked the beginning of regular northern military intervention in the Deccan.

Further expansion followed. In 1310, Alauddin’s general Malik Kafur invaded the Berar region, which borders modern-day Parbhani. According to the district Gazetteer (1967), Sankar, son of Ramchandra of Devagiri, was killed in this campaign after refusing to pay tribute. This invasion brought the wider region, including Parbhani, into the Delhi Sultanate’s sphere of control.

However, the Tughlaq rule that followed remained unstable. From 1320 onward, under Ghiyas-ud-din Tughlaq and his successors, the Delhi Sultanate faced constant rebellions and the burden of military campaigns. To fund these efforts, the rulers imposed heavy taxes and demanded forced labour, which likely placed severe pressure on local populations. In frontier regions like Berar, which included areas such as Parbhani, these demands would have been felt especially strongly.

Rise of the Bahmani Sultanate

Amid growing discontent, a major event in the history of the Deccan region occurred in 1347. Alauddin Bahman Shah, once a commander under the Tughlaqs, declared independence and founded the Bahmani Sultanate. With its capital initially at Gulbarga (Karnataka), the new state reorganized the region into four main provinces: Berar, Daulatabad, Bidar, and Gulbarga. Parbhani, most likely, was included in the Berar province.

Under Muhammad Shah I, the Bahmanis introduced administrative reforms. He personally toured frontier areas when possible, emphasizing stronger provincial oversight. By the late 15th century, Berar was subdivided into two divisions: Gavil in the north, and Mahur in the south—Parbhani fell into the Mahur division.

Although the Bahmani rulers maintained internal order for a time, they were often at war—with the Vijayanagara Empire, the Gond kingdoms, and other Deccan Sultanates. These conflicts strained the state’s resources, including those drawn from Berar. In places like Parbhani, this likely meant increased pressure on local communities through taxation, labour demands, or disruptions to farming and trade. Accounts from the Russian traveller Athanasius Nikitin, who visited India between 1469 and 1474, provide some insights into the life and social conditions during this period.

The Contest Over Pathri and the Struggles for Berar

By the early years of the sixteenth century, the Bahmani Sultanate had broken into a number of successor states, each vying for control of the Deccan. Of these, the Imad Shahi dynasty of Berar, under the reign of Alauddin Imad Shah, is known to have held sway over many parts of the present-day Parbhani district.

At this time, the town of Pathri, situated on the border between Berar and the Ahmednagar Sultanate, assumed strategic importance. Aware of its vulnerability, Alauddin fortified the town as a precaution against encroachment from the south. In 1510, upon succeeding his father Fatehullah Imad Shah, he refused a demand from Burhan Nizam Shah of Ahmadnagar to cede the town. In consequence, the Ahmadnagar Sultanate launched a military campaign and captured Pathri in 1518.

Some years later, in 1527, Alauddin regained the town with assistance from the Qutb Shahis of Golconda. The recovery, however, proved short-lived. The Sultan of Ahmednagar, now allied with the Barid Shahis of Bidar, returned in force. The combined armies defeated Alauddin, razed the fort at Pathri, and reasserted control over the town.

Still intent on reclaiming his territory, Alauddin sought support from the kingdom of Khandesh. The alliance was formed, but the campaign that followed met with little success. In 1524, the armies of Ahmadnagar and Bidar Sultanates prevailed once again. The province of Berar, including Pathri and Parbhani, was formally annexed to the Ahmednagar Sultanate, and the rule of the Imad Shahis came to an end.

During the following decades, Berar became a contested territory among Deccan powers. In 1565, it was again invaded by the Ahmadnagar Sultanate. The district Gazetteer (1967) records that this invasion resulted in the destruction of towns and the massacre of inhabitants, and probably also affected Parbhani. A final treaty signed in 1572 between the Bijapur and Ahmadnagar Sultanates formalised Berar’s annexation, consolidating it under Ahmadnagar rule.

In 1590, the death of Burhan Nizam Shah left the Sultanate of Ahmadnagar in a state of political disorder. At this moment, the Mughal Empire under Emperor Akbar was extending its reach southwards. In 1596, Akbar’s fourth son, Sultan Murad, led an expedition into Ahmadnagar territory. The resistance that followed was notable not for the strength of the Sultanate's forces, but for the figure who led them, Chand Bibi, aunt to the minor king Bahadur Shah, who had been nominally placed on the throne the year before.

Chand Bibi, though faced with internal divisions and limited support, maintained a steady defence of Ahmadnagar against the Mughal advance. However, her position was undermined by a lack of reinforcements and by disunity among the local nobility. Unable to sustain a prolonged resistance, she was obliged to come to terms. As part of the settlement, the province of Berar was ceded to the Mughals in return for peace.

The Battle of Sonpeth (1597)

Yet the settlement did not bring an end to hostilities. The Ahmadnagar state, though weakened, continued to resist. On the 8th of February 1597, a Mughal force under Khan-i-Khanan advanced towards the pargana of Pathri, located in what is now the Parbhani district. Their aim was to consolidate Mughal authority in the recently acquired territories. The movement of the army brought them to the banks of the Wan River, near the settlement of Sonpeth, some 24 km from Gangakhed.

Here, the Mughal advance was checked. In the engagement that followed, the Mughal force suffered a defeat, and their progress was temporarily halted. This reverse, however, proved to be a delay rather than a turning point. Reinforcements were promptly dispatched, and operations resumed shortly thereafter.

In the meantime, efforts were made by the remaining Deccan sultanates to check Mughal expansion. The Ahmadnagar Sultanate entered into a renewed alliance with the Bijapur and Golconda Sultanates. Despite this, the coalition failed to offer any lasting resistance. The Mughals pressed forward, and after a series of campaigns, Ahmadnagar city itself was captured. In the course of these events, Chand Bibi was killed during a palace mutiny, bringing her leadership to a close. With her death and the fall of the capital, Berar—including the area comprising modern Parbhani—was firmly brought under Mughal control and incorporated into the administrative framework that followed.

Parbhani Under the Mughals

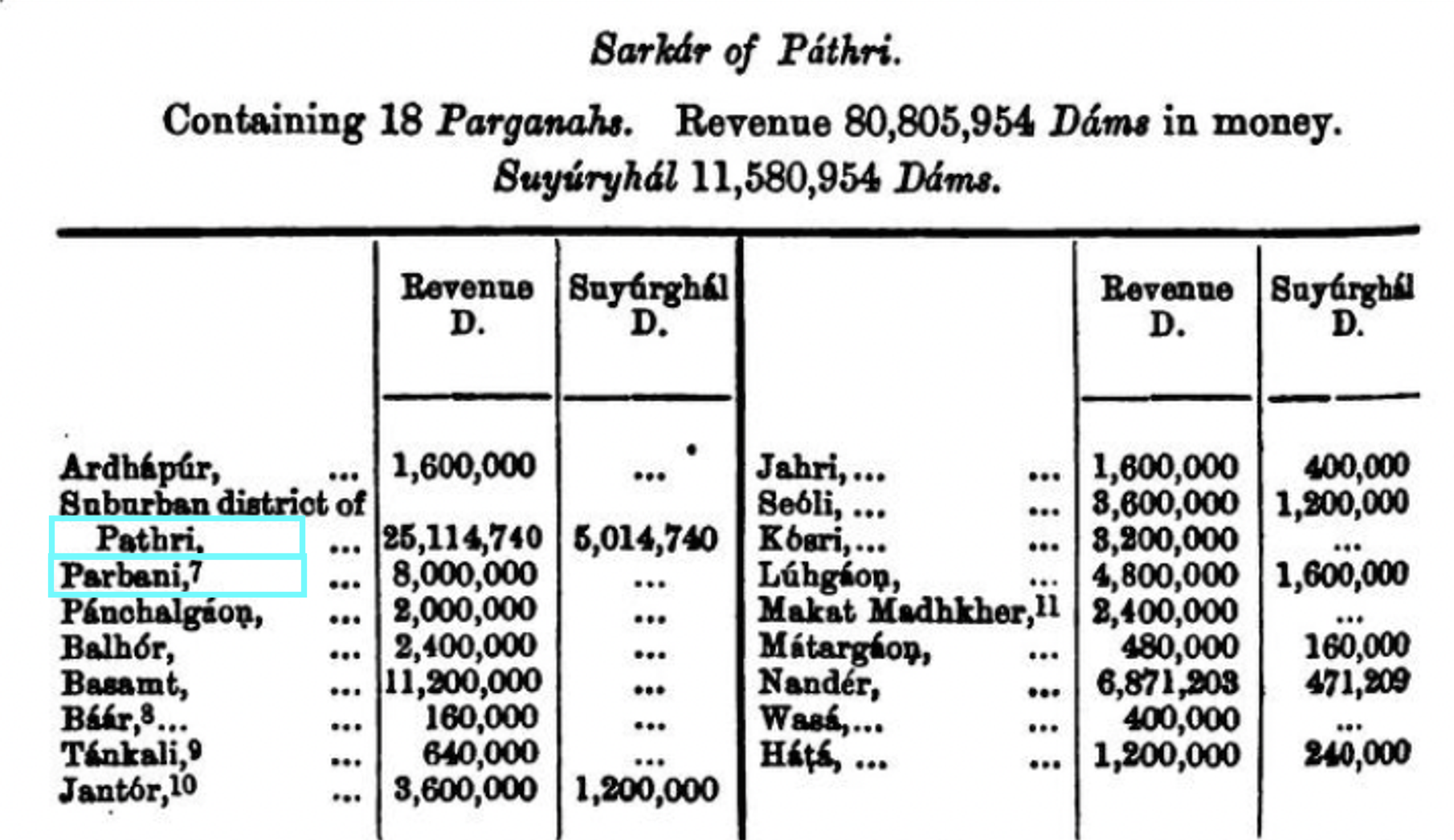

The present-day region of Parbhani, in the administrative system of the Mughals, formed part of the sarkar of Berar. The Ain-i-Akbari, compiled by Abul Fazl during the reign of Akbar, provides the earliest detailed account of this region under Mughal rule. According to this source, Berar was divided into sixteen sarkars, or districts. Of these, Pathri was among the more prominent and comprised eighteen parganas or subordinate units.

Interestingly, the revenues collected from Pathri were recorded at 80,805,954 dams, a figure that placed it as the third most valuable district in Berar. Only Gawil and Narnala, both located farther to the north, surpassed it in assessed income. This substantial revenue suggests a region of considerable fertility. Whether the wealth arose from cultivated grain, cotton, or the proceeds of trade, the district’s importance cannot be overlooked. The Ain-i-Akbari also makes special mention of Jintur, a town within present-day Parbhani, describing it as a flourishing market centre. Taken together, these references indicate that Parbhani was a place of much importance in the economic landscape of the Deccan region.

With Akbar’s death in 1605, the throne passed to his son Jahangir. During Jahangir’s reign, Berar remained relatively peaceful. Matters changed once more in 1627, following Jahangir’s death. A dispute over the succession again convulsed the Mughal court, and for a brief period, the outcome was uncertain. In the end, it was Shah Jahan who prevailed, assuming power in 1628. His rule was followed, in due course, by that of Aurangzeb—who, unlike his predecessors, would spend a considerable part of his reign engaged in warfare across the Deccan region.

Throughout this period, it is noted that control over the southern provinces remained a matter of difficulty. The methods used in the north—reliant on formal land assessments, standing armies, and local governors—proved ill-suited to the terrain and political conditions of the Deccan region. The effects of this unstable governance were undoubtedly felt among the local population, including those living in Parbhani.

Marathas

By the latter half of the 17th century, a new power had emerged from the western ghats. Under the leadership of Chhatrapati Shivaji, the Marathas had begun to consolidate control over large areas of the Deccan. Shivaji's aim was the establishment of a distinct Maratha state, and to that end he carried out a series of bold campaigns across the region. In 1670, he launched a major offensive into Mughal-held Berar and Khandesh, resulting in widespread plunder and disruption. It is likely that Parbhani, then part of Berar, suffered from the disorder that accompanied this campaign.

Following Shivaji’s death in 1680, his son Sambhaji continued the struggle, keeping up pressure on the Mughal garrisons in the Deccan. The contest between the Marathas and the Mughal court continued until Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, and even thereafter, the conflict was carried on by his successors and rivals. By the early decades of the 18th century, Mughal control in the Deccan had weakened considerably.

The Do-Amli System in Parbhani

With the decline of Mughal authority in the early 18th century, control of the Deccan passed into the hands of regional powers. Among these was the Hyderabad state, established by Asaf Jah, a former Mughal noble appointed Subedar of the Deccan in 1713. In 1724, following his victory at Sindkhed, he asserted autonomy and took the title of Nizam-ul-Mulk. Berar, including Parbhani, came under his authority.

However, the Nizam’s position in Berar was challenged by the Marathas, who had by then extended their influence into the region. In 1728, after surrounding the Nizam’s army at Palkhed, the Marathas secured the right to collect chauth and sardeshmukhi from the Deccan, including Berar.

This resulted in a dual revenue arrangement known as the Do-Amli system. Under this arrangement, the Nizam retained administrative control, but Maratha agents, particularly from the Peshwas, were entitled to a share of the revenue. In districts such as Parbhani, both sets of officials operated side by side, often collecting from the same villages.

In 1752, a treaty between the Nizam and the Marathas led to the cession of the western half of Berar—between the Godavari and Tapi rivers—to the Maratha state. It is likely that parts of Parbhani passed into Maratha control at this time, though boundaries were not clearly defined. The Do-Amli arrangement continued in effect, in various forms, until the early 19th century, when increasing British influence brought about administrative consolidation.

British Involvement and Integration into Hyderabad

By the close of the 18th century, the British East India Company had begun establishing its presence in the Deccan. In 1798, the Nizam entered into a subsidiary alliance with the Company, making Hyderabad the first princely state to do so. In 1803, during renewed hostilities, joint British and Nizam forces advanced into Berar. The Raja of Nagpur, under pressure, withdrew his claims, surrendering all territories gained since 1748.

In consequence, Parbhani passed fully into Hyderabad State, administered under the Nizams. Although open warfare subsided, the region continued to suffer from administrative weakness. Pindaris, Naiks, and other bandit groups frequently raided villages, and public security remained poor.

Persistent disorder and the Nizam’s mounting debt led to the Treaty of 1853, under which British officers assumed direct control over the administration of Berar, including Parbhani, though it formally remained part of the Hyderabad dominion.

Nizams Under the British Paramountancy

Following its integration into the Hyderabad State in the 18th century, Parbhani remained under the rule of the Nizams during the period of British paramountcy. According to the Gazetteer (1909), the district was divided into several talukas, each with distinct geographical and economic characteristics. The major talukas included Jintur, Hingoli, and Kalamnūri, all situated on the Sahyadri plateau, characterized by forested regions, wildlife, and a mix of agriculture. The total population of Parbhani in 1901 was 5,35,027, with 58% of the people engaged in farming. The majority were Hindus, primarily Marathi-speaking, though there were also Muslims and Jain communities. In 1905, parts of Nanded were merged into Parbhani, leading to administrative changes in taluka boundaries.

The First War of Independence (1857)

The long standing alliance of the Nizam’s state with the British continued even during the Revolt of 1857, which was the first major uprising in India against the imperialists. This alliance plunged Southern India into a state of turmoil. Across every region, small groups rose in revolt against the British occupation. Among these, the Rohillas sought refuge in Parbhani district, only to face severe counterattack at the hands of the British. The jagirdar who extended the sanctuary was subsequently apprehended and sentenced to two years of imprisonment. Such disturbances persisted until the end of 1860.

After the 1857 Revolt, the administration of the State of Hyderabad, including Parbhani, underwent a profound transformation. According to the gazetteer (1967), the state's governance became more structured, marked by the appointment of salaried officials at tehsils and districts. Departments for education and health were established, and civil and district courts were instituted for greater control. It is plausible that this emulation of British administrative practices also facilitated the dissemination of colonial ideologies and values. Nonetheless, Salar Jung, the prime minister of the Hyderabad state in 1853, attempted to strike a balance between the indigenous culture and English influences.

Commerce

Throughout the nineteenth century, Parbhani’s markets were closely tied to the trade routes running between Hyderabad and Mumbai. Merchant groups such as the Vanis, Komatis, and Marwaris managed much of the local exchange, while Bhatias and Kachchis from Bombay handled exports. In 1900, the opening of the Hyderabad–Godavari Valley Railway altered these long-standing routes, drawing trade away from the old caravan paths and binding the district more firmly into a modern transport network.

By the early twentieth century, cotton, linseed, oils, ghee, muslin, indigo, and food grains were leaving Parbhani for Bombay and Hyderabad. In return came cloth, silk, precious metals, rice, sugar, kerosene, opium, and metalware. The district’s economy, in this way, became linked to distant markets by rail.

Post-Independence Era

After India’s independence in 1947, Parbhani remained part of the princely state of Hyderabad. The Nizam, Mir Osman Ali Khan, initially refused to accede to the Indian Union, despite growing support for integration among the population. The situation in the state became increasingly tense, marked by communal unrest that led many to seek refuge outside Hyderabad’s borders. Local workers and political activists in Parbhani were active in the movement supporting integration.

In September 1948, the Government of India launched Operation Polo, a military operation that led to the swift annexation of Hyderabad. The princely state was formally merged with the Indian Union on 17 September 1948.

Parbhani then became part of Hyderabad State within the Indian Union. Following the States Reorganisation Act of 1956, the Marathi-speaking districts of the former Hyderabad State, including Parbhani, were transferred to Bombay State.

With the formation of Maharashtra on 1 May 1960, Parbhani became one of its districts. Later, in 1999, the Hingoli district was carved out of Parbhani.

Reforms and Industrial Development

Parbhani district has historically been rooted in agriculture, and this continued to shape its economy and social structure after independence. In the early decades, farming remained the primary occupation, and small-scale agro-processing units such as dal mills, oil mills, and ginning presses emerged in and around the town. These provided seasonal employment to local labourers and supported the surrounding rural economy.

In the 1970s, changes in the educational and industrial landscape began to take shape. In 1972, notably, the Vasantrao Naik Marathwada Krishi Vidyapeeth was established in Parbhani. It grew out of the Agricultural College that had been functioning in the town since 1956. This was the first agricultural university in Maharashtra, and it became an important centre for agricultural research and education in the region.

In the same decade, efforts were also made to support industrial development. The District Industries Centre (DIC) was set up in 1978, and the first MIDC industrial estate in Parbhani was established in 1982. These initiatives aimed to promote small and medium enterprises.

The 1980s saw a rise in industrial activity with the establishment of several units, including MOSICOL (a government-owned oil extraction plant), Prabhavati Cotton Mill, Prayag Industries, Samrat Tiles, and others. However, many of these faced challenges such as poor planning, lack of market research, and administrative delays. By the early 2000s, most of these industries had shut down. Industrial plots allotted at subsidised rates were later sold or auctioned.

Today, agriculture continues to dominate the district’s economy, while industrial growth remains limited. The slowdown is often attributed to inadequate long-term planning and weak political backing for sustained industrial development.

Sources

Abul Fazl Allami. H.S. Jarrett trans. 1891.The Ain - I - Akbari. Vol. 2. Asiatic Society of Bengal.

D.R. Pradhan et al. 1980. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Parbhani District. Government Central Press, Mumbai.

Dr. Pravin J. Nadre. 2020.Parbhani and Hingoli Districts: Ancient times. Vol 7. Issue 12, Ayushi International Interdisciplinary Research Journal.http://www.aiirjournal.com/uploads/Articles/…

Facts and Details. After Ashoka and the Maurya Empire: Shungas, Satavahanas and the Saka Migrations (185 B.C. to A.D. 195).https://factsanddetails.com/india/History/su…

Faisal Malik. 2020.Controversy over birthplace of Sai Baba ends after CM Uddhav Thackeray’s intervention. Hindustan Times.https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/contro…

Gopal Joge. 2013. Recent Explorations in the Khadak-Purna Basin of Maharashtra. Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute (Deemed University).https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312…

His Highness The Nizam's Government. 1884.Gazetteer Of Aurangabad. The Times Of India Steam Press.

Jadunath Sarkar. 1949.Ain-i-Akbari of Abul-Fazl-Allami. Volume 2. Ed.2. Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, Kolkata.

Jayaram. 2010.Pathri Fort. Trekking Experiences!https://jayaram-trekking.blogspot.com/2010/0…

Ketaki Gara. 1970-71.Indian Archaeology 1970-21 - A Review. Archeological Survey of India, Government of India, New Delhi, India.https://archive.org/details/indianarchaeolog…

Maharashtra State Gazetteer.History, Part II, Chapter 10: Mediaevil Administration and Social Organisation. Directorate of Government Printing, Mumbai.https://gazetteers.maharashtra.gov.in/cultur…

Poulami Ray. 2023.Visualising Region in History: Analytical Study of Evolution of Vidarbha as a Region. Volume 7. Athena.http://athenajournalcbm.in/Pdf/Article/2023/…

Pravin J Nadre. 2020. “Parbhani Districts in Mughal Era.” Vol 7, no 12, Aayushi International Interdisciplinary Research Journal (AIIRJ).https://www.aiirjournal.com/uploads/Articles…

Ravindra Jadhav et al. 2010.Town Level Background Note, Parbhani. Resources and Livelihoods Group, PRAYAS, Pune.https://urk.tiss.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019…

Shireen Moosvi. 1982.The Mughal Empire and the Deccan—Economic Factors and Consequences. Vol. 43. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress.https://www.jstor.org/stable/44141249

Social and Cultural History of India (from Earliest to 1707 A.D.)An MHRD Project under its National Mission on Education through ICT.https://epgp.inflibnet.ac.in/epgpdata/upload…

Sunil Purushotham. 2021.From Raj to Republic: Sovereignty, Violence, and Democracy in India. Stanford University Press.

Temples of India. Amruteshwar Temple, Ratanwadi.https://templesofindia.org/temple-view/amrut…

Vedika D. Shitre, Suraj Kapale. 2023. A study on the Hatti Barav Elephanta Stepwell: The traditional water harvesting system in India. Archeological Survey of India.https://static.mygov.in/static/s3fs-public/m…

Websites Referred:Parbhani District: Official website, Wikipedia

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.