Contents

- Architecture of Prominent Sites

- Bhimashankar Mandir

- Shaniwar Wada

- Parvati Hill Complex

- St. Paul’s Church

- College of Engineering, Pune

- Fergusson College

- Mahatma Phule Mandai

- Aga Khan Palace

- Bank of Maharashtra Building

- Residential Architecture

- Residences from the 1860s on the Rajwada Road in Bhor Village

- Bhausaheb Rangari Wada in Budhwar Peth

- A Residence from the mid-20th Century in Velhe

- A Residence from the late 20th Century in Velhe

- A Residential Building from 2000s in Bibwewadi

- A Residential Building from 2010s in Dhankawadi

- A Residential Township from the early 21st Century in Hinjewadi

- Sources

PUNE

Architecture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Architecture of Prominent Sites

From early medieval mandirs like Bhimashankar Mandir, which showcases Nagara and Maratha architectural styles, to Peshwa-era wadas and vibrant peths, Pune's architecture reflects a layered coexistence of dynastic and imperial influences. The arrival of the British introduced new typologies, such as military barracks, Gothic churches, and civic buildings like the Mahatma Phule Mandai. Post-independence, the city saw the emergence of Art Deco and modernist forms, especially in institutional and residential buildings. These shifts reveal not just stylistic changes but the evolving social fabric and aspirations of a growing urban centre.

Bhimashankar Mandir

The Bhimashankar Mandir, located in the Khed taluka of Pune district, is a notable example of the Nagara style of Mandir architecture, a tradition rooted in northern India and adapted in the Deccan over centuries. Though the exact date of its original construction is uncertain, literary and inscriptional sources suggest the Mandir dates back to the early 13th century. Over the centuries, it has seen several additions and renovations, particularly under the patronage of Maratha leaders such as Chimaji Antaji Nayik Bhinde and Nana Phadnavis. The Mandir is one of the twelve Jyotirlinga devasthans of Bhagwan Shiv in India.

Architecturally, Bhimashankar Mandir preserves an archaic Nagara form rarely found in the Deccan, with subtle influences from the Hemadpanthi style visible in the stone masonry and structural techniques. Built primarily from stone, the Mandir reflects an older form of the Nagara tradition, evident in its simple yet elegant proportions and simple ornamentation. The Mandir is best known for its shikhara (spire), rising above the garbhagriha (sanctum), crowned by an amalaka and kalasha, both hallmark features of the Nagara style. Elements such as devakoshtas, dome-shaped roofs, and traces of lime-sand sculptures further reflect the Mandir’s layered architectural history.

![Shikhara of Bhimashankar Mandir showcasing Nagara Mandir architecture, marked by a tiered vertical form.[1]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/pune/architecture/shikhara-of-bhimashankar-mandir-showcasing-_Mra7pjs.png)

The Mandir complex includes a sabhamandap (assembly hall) added during the 18th century Peshwa period and a Portuguese bell believed to have been brought from Vasai after the Maratha victory in 1739. The Mandir features a garbhagriha, gudhamandap (enclosed pavilion), and mukhamandap (entrance hall), with carved pillars, court spaces, and carvings that are tied to epic stories. The garbhagriha houses a swayambhu Jyotirlinga, placed at a slightly lower level, directly beneath the shikhara. The garbhagriha connects to an antarala and a gudhamandap, both supported by carved stone pillars. The pillars and door frames display carvings of Devis, Devtas, and other narrative figures, showing influence from Jain mandir art.

Situated on a high platform amidst the forested hills of the Bhimashankar Wildlife Sanctuary, the Mandir integrates sacred architecture with its natural surroundings. Bhimashankar Mandir’s architecture preserves an early form of Nagara style, with a simple exterior. Its design shows continuity with northern mandir forms, adapted with local materials and techniques, making it a notable architectural example in the district.

Shaniwar Wada

In the 18th century, Pune emerged as a prominent urban center under the leadership of the Peshwas (1730–1818). Their rule was marked by extensive infrastructural and civic development, including the construction of mandirs, bridges, and residential zones. The Peshwas’ cultural and religious values, in many ways, imparted a Brahmanical character to the city, which became a defining feature of its identity during this period.

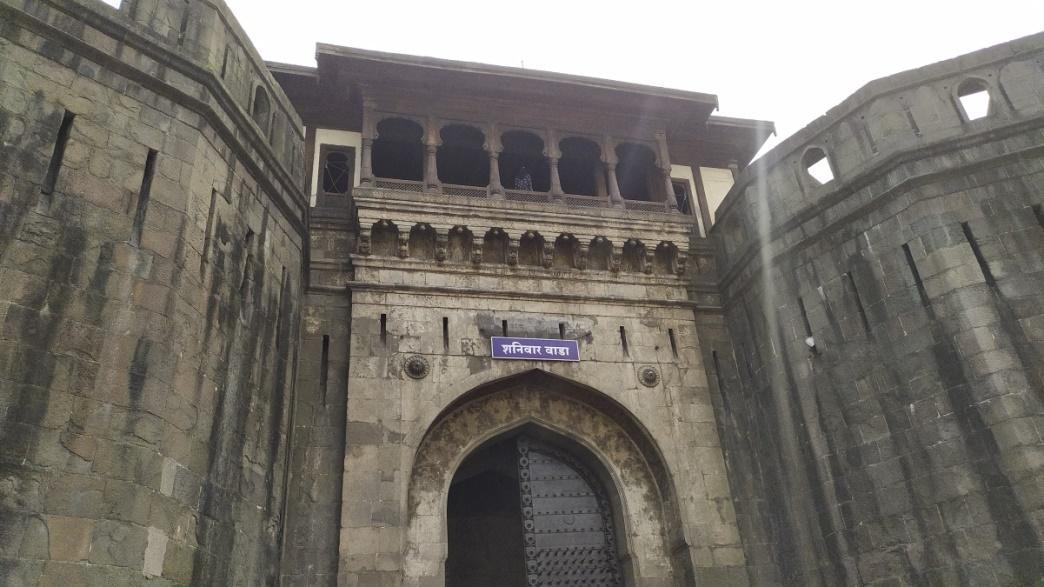

Among the architectural landmarks of this period was Shaniwar Wada, a notable example of wada architecture. Built in 1732 by Peshwa Bajirao I as his official residence, it served as the seat of Peshwa power and stands as a symbol of 18th-century Maratha administration, culture, and architectural vision.

Wada architecture refers to large courtyard houses constructed using local materials and techniques, influenced by Maratha, Mughal, Rajasthani, and Gujarati styles. Originally designed to house single or multiple families, wadas typically featured central courtyards that allowed for light and ventilation, with thick walls and minimal exterior openings suited to Pune’s tropical climate. The layouts reflected social hierarchies and domestic life, prioritizing privacy and climate responsiveness, while incorporating ornate wooden facades and carved detailing. Unlike fortified garhis, wadas were often more ornamented externally, with decorated openings across structural bays.

Shaniwar Wada followed this traditional layout, with rooms arranged around courtyards, supported by carved wooden pillars, balconies, and richly decorated limestone niches. The wada once rose to seven storeys and featured four major courts, each dedicated to specific functions such as administration or celebration. Key halls like the Ganpati Rangmahal and Nachacha Diwan showcased elaborate woodwork with enamel and gold detailing, along with ornate fountains. Special rooms served as a treasury, library, armoury, picture gallery, and more.

The wada was enclosed by 20-foot-high walls, five ft. of stone topped with 15 ft. of brick. The wada has five massive wooden doors: Delhi Darwaza (the main gate facing Delhi), Mastani Darwaza, Khidki Darwaza, Ganesh Darwaza, and Narayan Darwaza. These were flanked by nine bastions. Within its walls were gardens, fountains, and the Hazari Karanje, a Mughal-influenced ornamental fountain with a thousand spouts. Above the main gate stood the Nagarkhana, where drums and shehnais were played each day announcing the grandeur of the Peshwa court.

Parvati Hill Complex

The Parvati Hill Complex, constructed by Nanasaheb Peshwa in the mid-18th century, is a prominent example of religious architecture from the Peshwa period. One of Pune's oldest heritage sites, it served both as a place of worship and as a strategic observation point due to its elevated position overlooking the city.

Built in the traditional Peshwa-era architectural style, the complex displays stone masonry and carved shikharas that are distinct from the stucco shikharas seen in later Mandir styles. The fortified complex consists of five principal mandirs and is flanked by arched landings and retaining walls.

![The Devadeveshwar Mandir in the Parvati Hill mandir complex showcasing an architectural style prominent during the Peshwa-era.[2]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/pune/architecture/the-devadeveshwar-mandir-in-the-parvati-hil_TbHcq9g.jpg)

St. Paul’s Church

Following the decline of Peshwa rule and the British victory in the Battle of Kirkee (1817), Pune began transitioning into a colonial administrative and military hub. This shift led to the establishment of the British Cantonment outside the old city, introducing European spatial planning and architectural styles to the region.

One such example of British architectural influence is St. Paul’s Church, located on Agarkar Road and constructed in 1867. Designed by Rev. F. Gell, the church reflects early English Gothic architectural elements, inspired by Sainte-Chapelle in Paris. Its features include narrow pointed arches, a bell tower, gargoyles, and, originally, a high-pitched roof of corrugated iron that was later destroyed in a fire.

Gothic architecture, which originated in medieval Europe, is characterized by pointed arches, soaring spires, flying buttresses, and stained-glass windows. These elements were adopted in several colonial-era buildings in Pune, particularly religious and educational institutions, as part of a broader cultural shift introduced by the British.

![St. Paul’s Church featuring distinctive English Gothic style architecture.[3]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/pune/architecture/st-pauls-church-featuring-distinctive-engli_rKzy0K8.png)

In addition to St. Paul’s, many other churches were established across the growing city during this time, incorporating Gothic and Neo-Gothic design principles. Notable examples include St. Xavier’s Church in Camp, All Saints’ Church in Khadki, St. Crispin’s Church in Erandwane, and St. Patrick’s Cathedral, which prominently reflects Neo-Gothic architecture. These structures collectively demonstrate the colonial imprint on Pune’s architectural identity.

College of Engineering, Pune

The College of Engineering, Pune, showcasing Gothic Revival architecture, was established in 1854 and is among the earliest technical institutions in India. It was originally formed as the Poona Engineering Class and Mechanical School and was later developed as a college.

The main building, designed by W.S. Howard is an important example of Gothic Revival architecture in Pune, reflecting the broader British architectural influence that shaped much of the city’s 19th-century institutional landscape. The style features classic Gothic elements like pointed arches, vaulted ceilings, and symmetrical stone façades, adapted to suit the academic setting and tropical climate. The imposing structure uses load-bearing stone walls, slender windows, and prominent arches to create a sense of formality and grandeur.

![College of Engineering Pune is an example of European Gothic revival architecture.[4]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/pune/architecture/college-of-engineering-pune-is-an-example-o_kunkDvA.png)

Fergusson College

Fergusson College showcases Victorian-Gothic architectural features such as pointed arches, exposed stone masonry, sloping tiled roofs, and arched verandas. Built in 1885, it is one of Pune’s most prominent educational institutions from the colonial period. Established by the Deccan Education Society and led by visionaries like Lokmanya Tilak, Gopal Ganesh Agarkar, and Gopal Krishna Gokhale, it was named after Sir James Fergusson, then Governor of Bombay. The main college building was designed and executed by Rao Bahadur Vasudev Balwant Kanitkar.

The main building showcases Victorian-Gothic architectural features which reflect a colonial-era adaptation of European styles, set within a 65-acre, tree-lined campus that blends formal British planning with regional construction methods.

![Fergusson College is a prominent landmark in Pune featuring Gothic-style architecture.[5]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/pune/architecture/fergusson-college-is-a-prominent-landmark-i_XIUABa6.png)

Mahatma Phule Mandai

Among the most notable civic structures from the British era is the Mahatma Phule Mandai, originally known as Reay Market. Constructed between 1882 and 1886 in a Gothic architectural style, the market is located in Shukrawar Peth and features a distinctive octagonal central tower and eight arched entrances. Designed to serve as a retail and wholesale vegetable market, it was named after Lord Reay, then Governor of Bombay.

Following independence, the market was renamed in honour of Mahatma Jyotirao Phule, the prominent social reformer from Pune. Even today, Mahatma Phule Mandai functions as the city’s largest vegetable market with over 520 stalls. Notably, the structure remains a symbol of Pune’s colonial past and is a relic of British civic architecture.

![Mahatma Phule Mandai is built in a distinctive Gothic architectural style and is a notable symbol of Pune’s colonial past[6]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/pune/architecture/mahatma-phule-mandai-is-built-in-a-distinct_vOjepFJ.png)

Aga Khan Palace

The Aga Khan Palace, featuring the Indo-Saracenic architectural style, is a prominent example of British-era architecture in Pune. Constructed in 1892 by Sir Sultan Muhammed Shah Aga Khan III, the palace was originally intended as a charitable project during a famine, but later functioned as a seasonal residence. The architectural style blends Islamic and Indian influences with colonial-British elements. The building follows a barrack-style plan, with barn-like chambers connected through arcaded verandas rather than interior corridors. Its stuccoed brick walls, stone base, and pitched roof supported by decorative iron cantilevers define its structural composition.

Key features include Italian arches, wooden beams, stone and wood flooring, and an entrance hall with clerestory windows, Gothic tracery, and rose windows. The porch, adorned with medallions marked ‘H.H.A.K.’ (abbreviation for His Highness the Aga Khan), is supported by ornate arches and flanked by corner pavilions with hipped tiled roofs. The verandas across each level feature black stone columns below and white balustraded columns above, divided into bays by pilasters. The building’s form and ornamentation exemplify the colonial-era aesthetic while reflecting a blend of Indian and European traditions.

Bank of Maharashtra Building

Following the British colonial period, Pune’s architectural landscape began to reflect new aspirations shaped by independence and modernity. The mid-20th century saw the emergence of Art Deco influences, marking a shift from colonial styles toward contemporary forms.

A notable example of this transition is the Bank of Maharashtra building on Bajirao Road in Budhwar Peth, a prominent Art Deco structure in Pune. This building, designed by architect U. M. Apte was constructed in two phases—1954 and 1969. It is inspired by Hamam Street in Fort, Mumbai, and reflects a unique blend of Art Deco and traditional Indian elements. While advances in construction technology progressed more slowly than aesthetic developments, the building is a notable example of Pune’s evolving architectural ambitions during this period.

![The Bank of Maharashtra building in Budhwar Peth is an example of Art Deco architecture.[7]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/pune/architecture/the-bank-of-maharashtra-building-in-budhwar_LU9dOA6.png)

The building’s central tower is topped with a chhatri, stylized in an austere, octagonal shape. The facade of the wings flanking on either side of the tower is organised in a uniform, geometric grid, divided by long buttresses. The structure avoids the typical horizontal streamlining seen in most Art Deco designs and instead emphasizes verticality through painted bands that contrast with the stone façade. These elements create a monumental effect and have come to define the visual identity of Pune’s Art Deco movement.

Residential Architecture

In Pune, the architecture of homes has seen a temporal change over the centuries. Each residential structure carries the imprint of local history, community life, and a distinctive cultural identity of the district’s many inhabitants in the representative era. As time passes, it is fascinating to see how the private space of ‘home’ has been reimagined across different eras, often affected by the larger ‘public’ trends that take place outside of it. Traditional wada, representative of architecture trends rooted in Peshwa and Maratha culture, have gradually given way to townships built according to contemporary architecture practices, reflecting shifts in lifestyle and construction techniques. These changes mirror broader patterns of urbanization, population growth, and evolving cultural dynamics across the district, shaping not only the built environment but also the lived experiences of its residents.

Residences from the 1860s on the Rajwada Road in Bhor Village

Bhor, once a princely state, is a historical village in Maharashtra known for its scenic beauty and historical sites. The village is home to the Bhor Rajwada, the official, royal residence and seat of the Rajas of the princely state. Royal residences offer a window into the lives of those who once ruled, reflecting their tastes, traditions, and the architectural styles of their time. The areas surrounding the wadas, too, bear remnants of their historical past. The Bhor Rajwada, built in 1869 by Raja Chimnaji Raghunathrao III (ninth ruler of Bhor), stands as a testament to a legacy within the Maratha tradition and borrows from European Renaissance Architecture with a blend of Indian Vernacular and Gothic styles.

Surrounding the palace are old wadas, once home to families connected to the royal household, some of which now house government offices and shops. These wadas, like many in Pune’s historic core, embody the architectural and cultural influences of the Maratha and Peshwa periods.

These typically housed multiple families in a joint family system. However, some were later rented out, which altered their original living arrangements. The surrounding area, in many ways, is characteristic of a village settlement with homes tightly packed together and narrow lanes called “bolas” weaving between them. These bolas served as pathways leading to small aangans (courtyards) where a few houses were grouped together.

As a central architectural feature of wadas, courtyards were designed to accommodate multiple families or a single household, serving both ruling classes and commoners. These homes often included open verandahs and spacious courtyards, which provided ventilation and functioned as communal spaces for daily interactions. The narrow streets and aangans offer a sense of community by encouraging social interaction and building a close-knit community.

The old residences in this area follow a distinct architectural pattern characteristic of the period. The residences feature double shutter windows and doors, crafted from wood with panelled designs, though some doors are made of metal, which is perhaps a more recent addition.

In this Wada, the windows are proportionate to the doors, nearly matching them in height, creating a sense of uniformity in the structure. Small, high-placed windows with iron grills allow for ventilation while maintaining privacy within the house. The residences are built using a combination of materials, primarily cement and bricks.

Bhausaheb Rangari Wada in Budhwar Peth

The central city areas of Pune, the peths, form the city’s original urban settlement from the Peshwa period. During this time, wadas were a common style of residential architecture. Notably, many of the wadas in the Peth areas today are from this era.

Under British rule, Pune was part of the Bombay Presidency and became a center for anti-colonial activities. Many freedom fighters and social reformers, including Tilak, Gokhale, Ranade, Agarkar, Phule, and Karve, were active in the city. Alongside them were lesser-known figures whose homes became gathering places for discussions and planning. One such place was Bhausaheb Rangari Bhavan.

Bhausaheb Rangari aka Shrimant Bhausaheb Laxman Javale (1851-1905) was one of the great revolutionaries of Pune. It is estimated that he built his residence, the “Bhausaheb Rangari Wada”, in 1883 as a space for the community to come together with a common vision of freedom.

An Ayurvedic vaidya by profession, he dreamt of an independent India free from the British and was among the first to advocate for a sarvajanik (public) celebration of the Ganpati festival as a medium to rally people to the cause of freedom in Pune. In remembrance of this legacy, the wada continues to feature the main chariot of the Bhau Rangari Ganpati which was used initially by the trust to take out a public Ganeshotsava procession in Pune. It is still used today and has been maintained in its original form.

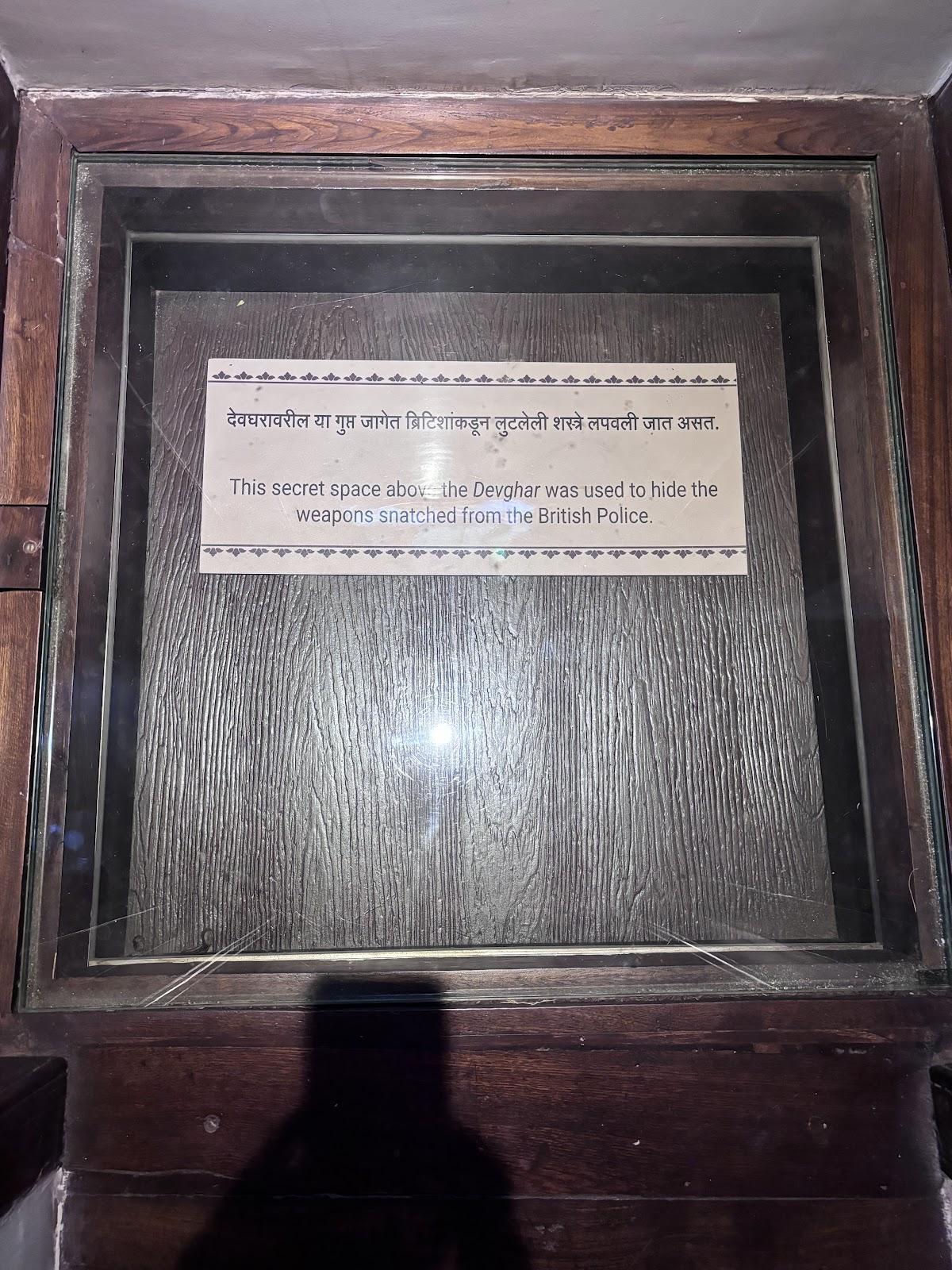

The wada bears many quiet traces of Bhausaheb’s legacy and his connections to the Freedom Movement. Above the devghar, a concealed compartment was built to hide weapons, swords and pistols said to have been taken from British police. In its own way, the house became part of a larger story, reflecting how residential spaces were tied into the currents of resistance.

The residence is a mix of wood and modern composite materials such as cement and bricks. The wada retains its original wooden features, such as staircases, doors, and windows. The Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC), with the help of its patron, Puneet Balan, restored the old wada in 2022, leaving its original features untouched.

The staircase leading to the first floor is narrow and made of wood. It has no central landing and is steeper than modern staircases.

The architectural details and elements of the residence are striking, and the use of wood is noticeable at first glance. The wada retains its original construction using bricks, wooden balconies, elongated rectangular windows and sloping roofs. The doors are constructed from wooden planks arranged in panel patterns. The main entrance door features a dark brown color with golden metal embellishments.

Traditionally, it is said that the doors of a wada represented the wealth and social status of the family residing within. While wadas of wealthier families would have heavily decorated doors as a show of their affluence while wadas belonging to the middle-class featured simpler wooden doors. The main entrance door of this residence follows that tradition, featuring a dark brown color with golden metal embellishments.

To the left of the entrance, there is a passage bordered by wooden railings. Below is a concealed underground passage which was used by the wada’s inhabitants to escape and hide from the British. While the tunnel appears to extend in both directions, a mirror has been placed at one end to mislead intruders.

On the second storey, each window is divided into three sections: an upper portion with stained glass, a middle portion for ventilation, and a bottom portion with railings. The latter two with panes that open outward to allow light entry. The windows on the top storey, too, are divided into two parts: the bottom is enclosed with grills while the top portion has panes that open outward to allow light and ventilation.

A Residence from the mid-20th Century in Velhe

Rajgad taluka in Pune district is home to several villages where local building traditions are tied closely to the landscape, climate, and materials found in the region. One such village is Velhe, where this residence, built around 80 years ago, sits at the edge of the main market street on contoured land.

The house rests on a plinth constructed from basalt stone on a perhaps uneven terrain. The exterior walls are made of bamboo sheets, coated with mud plaster and lime, blending the house with its surroundings while keeping the interior cool. The construction perhaps building practices typical to the region at the time.

The roof is made of a bamboo framework covered with metal sheets. Wooden columns serve as vertical supports, reinforcing the framework and complementing the rustic aesthetic of the house. The flooring, made from basalt stone, is left in its natural state, lending an earthy character to the space.

Notably, the spatial layout of the house appears to reflect the agrarian setting of the village and the occupational needs of its residents. It includes a cattle shed and storage areas for agricultural produce, along with a living room, a swayampak ghar (kitchen), and private rooms. A drain runs along the periphery of the structure to manage both rainwater and wastewater.

A Residence from the late 20th Century in Velhe

The main market street of Velhe bears remnants of past architectural features among the newer constructions. Built around the mid-1990s, this residence demonstrates a mix of old and recent architectural features with a structure of wooden framework and brickwork. Originally, locals say that the residences in the main market street of Velhe had a structure of wooden frameworks which burnt down in a fire in the market. More recently, residences are being constructed with composite materials such as bricks and cement. The below residence shares features from both eras – a partial wooden framework supplemented by brickwork.

The ground floor of the residence has a wooden verandah with stone tiling in the front of the house. Double-shuttered wooden doors open up to form a small convenience store in the centre and steps leading up to the second floor of the house where the family resides. The steps are concrete while the railings have a typical wooden top rail with vertical metal rod grills. The residence has a neutral color scheme with a pop of blue that highlights the convenience store.

A Residential Building from 2000s in Bibwewadi

As time passes, one can see how new architectural styles gradually begin to reshape the region’s landscape. Bibwewadi, a locality in the south of Pune city often described as a “developing area,” is evidence of this transition. Over the 21st Century, mid-rise buildings have increasingly become part of the locality’s built environment (a technical term for the human-made surroundings that make up a community). Among them is Tejashree Society, a residential society built in phases and completed around 2001.

The composite structure of the building very much aligns with urban mainstream practices of the current day. The building has a reinforced cement concrete (RCC) column structure with brick walls and a plaster finish. The project has been developed in phases with Phase II, III and IV within the same compound. Within Phase IV, there are two buildings, each of four storeys.

The main entrance has a mild steel grill door on the outside followed by an inside door which is wood and polish.

Notice, some windows of the building have a ‘Chajja’, a projected element just above the window, which shades the opening, stops rain from entering the room, and reduces sky glare while looking out of the room. Interestingly, the feature was popularized post-independence, and formal adoption was encouraged by standards set by the Public Works Department. Most other windows on the building are recessed windows and are fitted with metal grills and sliding glass panels.

The Phase IV buildings have an interesting modular color scheme with contrasting colors. The buildings appear to use contrasting rectangular sections of white, dark green and light brown while supporting columns in the garage have been painted olive green.

The society features two landscaped garden areas, accessible exclusively to its residents, fostering a shared community space within the modern residential complex. The first garden, located behind Phase IV, is densely covered with plants and features a natural stream, though its upkeep poses challenges.

The second garden, situated near the society’s entrance, serves as a gathering space for residents. These common spaces may serve as a modern reinterpretation of traditional courtyards found in wadas across the city, preserving their role as a focal point for social engagement. Semi-public gardens in residential societies offer a sense of community, much like common courtyards did in wadas.

A Residential Building from 2010s in Dhankawadi

Dhankawadi, another “developing area” in south Pune, shares a similar transformation journey as Bibwewadi. The area reflects coexistence between older low-rise structures and newer mid-rise buildings. Once a predominantly residential area, it has gradually incorporated commercial spaces, shaping its evolving built environment. Among the vast number of residential spaces is Kumar Panchsheel, a residential society, whose construction was completed in 2013.

The building’s design significantly differs from older homes of the district. It features a larger scale and a relatively more contemporary architectural approach which can typically be seen across many semi-urban and urban regions in the district. The composite structure of the building very much aligns with the mainstream practices of the current day.

The residential society is composed of two buildings, each of nine storeys and is located within the compounds of a bungalow society with an interior road leading to Kumar Panchsheel. The buildings feature a modular design with contrasting cream, light brown and grey panels.

The main entrance is a recessed door of polished wood with steel fittings.

Metal and glass has been used primarily for the design of the windows. The shutters are glass and have a sliding design, while the grills are metal and are painted white.

A Residential Township from the early 21st Century in Hinjewadi

Over the first few decades of the 21st century, Pune has seen the rise of integrated townships as a distinct phase in its urban development. These large, plotted settlements combine residential units with commercial, educational, and recreational infrastructure, emerging in response to rapid population growth and the pressures it placed on the city’s older housing models. By 2015, it has been noted that Pune had more such townships than any other city in Maharashtra, reflecting a broader shift toward planned, self-contained environments on its urban periphery.

Their growing appeal, in many ways, lies in the architectural promise of convenience with amenities, workplaces, and public spaces arranged within a single, planned compound. These townships are largely concentrated in Pune’s suburbs, where land is more readily available for large, plotted developments. One of the most prominent examples is Hinjewadi, a suburb whose transformation began around 2010 and is closely tied to the expansion of Pune’s tech industry. The Rajiv Gandhi Infotech Park, planned and developed by the Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC), was set up in phases and brought a wave of companies and jobs to the area.The influx of new employment opportunities created a growing demand for housing in the area, prompting the development of large-scale townships.

One of the earliest among them was Blue Ridge Township, which began construction in 2007. Situated within Phase I of the Rajiv Gandhi Infotech Park, it was designed to include not only residential towers but also a school, a shopping centre, sports facilities, and office spaces. Nearby are major IT companies like Wipro, Infosys, and Accenture, making it easier for many residents to live close to where they work.

The building’s design significantly differs from older constructions prevalent in the city and instead features a more contemporary architectural approach. Glass, cement, brick and metal makes up the composite structure of the residential towers, each around 25 storeys high which is taller than other construction projects in the vicinity.

The township offers one, two, three, four, and five BHK flats. The amenities and residential spaces are connected by a wide, cemented, two-way internal road shaded on either side by trees. Additionally, stone-tiled footpaths have been constructed within the township which are also shaded by trees.

The buildings are painted in a neutral palette featuring grey and white with a pop of yellow color mainly seen on the exterior of the top floors.

The main entrance door is a flush door with laminate on both sides and a digital locking system. Internal doors, too, are flush with laminate on both sides. The windows slide open and have powder coated aluminum frames with glass panels. The windows have no grills. The balcony doors, too, have powder coated aluminum frames with glass panels and have metal grills on the bottom half.

The balconies in the apartments are noticeably narrow, with only enough room for storage or keeping plants. The design, in many ways, acts as a compact extension of the living space.

The flooring across the apartments are vitrified tiles with only the master bedroom having wooden floorboards.

These new developments and changes in the architectural character of this space from the elements that one can find within the houses or the spatial layout of the whole township, in many ways, reflects how life in Pune is changing. The way these spaces are built, with everything carefully planned out, marks a new chapter in how the city is growing.

Sources

Adminhhsa. 2021. Know more about Chajja. Healthy Homes.https://healthyhomes.co.in/know-more-about-c…

Art Deco Pune. 2022. Bank of Maharashtra building, Bajirao Road, Budhwar Peth. Instagram.https://www.instagram.com/p/CeBY9A1DiDp/?img…

Behind Every Temple. Bhimashankar Temple. Behind Every Temple.https://behindeverytemple.org/hindu-temples/…

Dipanitha Nath. 2023. Know Your City: How COEP retains its status as a premier institute in India. The Indian Express.https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/pun…

Gaurav Kadam. 2023. Exploring Pune's Gothic Heritage: A Journey Through Architectural Splendour. The Free Press Journal.https://www.freepressjournal.in/pune/explori…

Government of India. Shaniwarwada. Indian Culture.https://indianculture.gov.in/snippets/shaniw…

Heritage Temples. Bhimashankar Temple, Talegaon-Dhamdhere. Heritage Temples.https://heritagetemples.org/pune-project/bhi…

Mi Punekar. 2021. Bhor Rajwada. Instagram.https://www.instagram.com/mipunekar.in/?hl=en

Nikita Mahajani. 2024. Art Deco Architecture in Pune from the 1940s to the 1960s. Vol 16, no. 2, Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities.https://rupkatha.com/V16/n2/v16n207g.pdf

Nisha Nambiar. 2025. Panel to inspect all integrated townships in Maha next year. The Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/pun…

Ramakrishna Nallathiga, Khyati Tewari, Susan Varghese, & Anshal Saboo. 2021. From Satellite Townships to Smart Townships: Evolution of Township Development in Pune, India. Vol. 16, no. 1. Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management.

Rishika Sood. Architecture of Indian Cities Pune- Queen of the Deccan. Rethinking The Future.https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/rtf-fre…

Samanata Kumar. 2022. The Architecture of Wadas of Maharashtra. Rethinking the Future.https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/rtf-fre…

Saurabh Agashe. 2019. Venerable trees and a gothic market: heritage-hunting in fast-changing Pune. The Guardian.https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/aug/…

Shoumojit Bannerjee. 2015. Fergusson College wins heritage status. The Hindu.https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other…

Sushant Kulkarni. 2022. Know Your City: How the Army’s Southern Command became an integral part of Pune’s history. Indian Express.https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/pun…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.