Contents

- The Petroglyphs of Ratnagiri

- Naman - The Musicals of Konkan

- Jakadi/Balya - Stories of Shravan during the Mid-Monsoon Respite

- Katkhel

- Handicraft

- Lohar Community of Ratnagiri

- Cultural Programs

- Art Circle Ratnagiri

- Annual Classical Music Festival

- Literary Programs

- Creative Spaces of the District

- Devrukh Museum

- Artists

- Bahinabai

- Sane Guruji

- Laxman Mahadeo Chitale

- Dada Salvi

- Pralhad Anant Dhond

- Onkar Bhojane

- Sources

RATNAGIRI

Artforms

Last updated on 22 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

The Petroglyphs of Ratnagiri

A petroglyph is a form of rock art where an image is typically etched onto surfaces using stone or rock tools. It is an ancient form of art that can be found across many parts of the world, with certain sites estimated to be up to 20,000 years old. In Ratnagiri, interestingly, these petroglyphs can be found at various sites, namely, Niwali, Barsu Suda, Ukshi, Agargaon, Devihasol, Bhalavali, Devache Gothane, Chave Dewod, Ganpatipule, Rundhe, Patharde, Jambharun, and Kasheli.

![A petroglyph with a complex geometric design, which lies in Niwali, Ratnagiri district.[1]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ratnagiri/artforms/a-petroglyph-with-a-complex-geometric-desi_qeLugPJ.png)

Many of these carvings appear on exposed laterite plateaus, often near roads, lying in plain sight. While some motifs repeat across locations, each site presents its own set of distinctive designs and imagery. Like many ancient art forms, the petroglyphs of Ratnagiri remain largely mysterious, with little known about their creators, purpose, or the stories attached to them.

Estimates suggest that these petroglyphs are between 10,000 and 12,000 years old, placing them in the Mesolithic period (a transitional era between nomadic hunting and early settled life). Surprisingly, however, the first recorded discovery of a petroglyph in the area was near Ratnagiri city, in the village of Niwali, during the 1980s. However, systematic documentation by the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Maharashtra, began very recently. By January 2019, it had been noted that over 1,000 petroglyphs had been documented across 52 sites in the region.

![A petroglyph in Barsu Sada which depicts what locals believe to be the Tarawacha Sada (Master of Animals). This interpretation comes from the imagery of animals surrounding the body of a human-like figure.[2]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ratnagiri/artforms/a-petroglyph-in-barsu-sada-which-depicts-w_ZftBKfF.png)

The carvings depict a variety of subjects, including static human figures, large mammals like elephants and tigers, aquatic life such as sharks and dolphins, and birds like peacocks and egrets. Some animals are unidentifiable, possibly representing extinct or momentous species. Notably, a petroglyph of a rhinoceros (a species not typically associated with the region) has been found.

In addition to these figures, the petroglyphs feature intricate geometric and abstract patterns composed of circular, oval, or rectangular shapes with complex internal designs. Scholars believe these designs were intentional and may have held ritualistic or deep significance. The effort required to carve into laterite rock with primitive tools suggests a deliberate and communal process, possibly indicating that these carvings were created by organized communities rather than isolated individuals.

Despite their historical importance, the petroglyphs face several threats. Locals say that urban development, mining, and construction activities, particularly due to the widespread use of laterite in buildings, have already led to the destruction of some sites. Many carvings are located on private land, where property owners may conceal or damage them due to fears of government intervention or land acquisition.

Awareness of these prehistoric carvings has grown in recent years. In 2022, nine petroglyphs from the Ratnagiri–Sindhudurg–Goa region were submitted for inclusion in UNESCO’s Tentative List of World Heritage Sites. Local organizations, such as Nisarga Yatri Sanstha, are working to educate the public through field visits, lectures, and workshops in schools and colleges. A dedicated research and documentation center has also been established in Ratnagiri to study and preserve these carvings.

While most people today may feel little connection to these ancient markings, efforts are underway to bridge that gap: linking early human creativity with contemporary understanding to ensure this heritage is not lost.

Naman - The Musicals of Konkan

Naman is a form of theatrical performance that involves music, dance, and storytelling. The story of the musical is of ‘epic proportions’ for it often features supernatural elements, lofty themes, and ample settings that are the typical characteristics of the epic genre. Like many traditional art forms in India, the exact origins of the musical are difficult to trace. However, what is known about its history is that it was originally known as Khele (खेळे) and emerged as a form of rural entertainment for the farmers of the Konkan region.

The art form can be commonly found in different parts of the Konkan region. Interestingly, each area maintains its own distinct local traditions within the broader performance style. In Sindhudurg, it is better known as Dashavtar, though the performance structure and themes remain closely related across regions.

Every Naman performance begins with a Ganpati Puja, seeking blessings for a smooth and successful presentation. The performances generally fall into two narrative types, namely, “Gan”, where episodes are centered on Ganpati, or stories from the Ramayan and Mahabharat. The other is “Gavlan”, where tales from Krishna Leela, such as the slaying of Kalia, Draupadi's Vastraharan, or Devaki’s wedding, are enacted. These narratives are often drawn from Puranic literature and epics but may be adapted by the Shahir (writer-director) for comedic or satirical effect.

Historically, Naman was performed exclusively by men. Due to social norms, women were not permitted on stage; instead, male performers would portray female roles, wearing sarees and ornaments with minimal makeup (typically kajal and a red dot). This convention is still seen today, though gradually changing. Today, women participate both as actors and in backstage roles, even as traditionalists sometimes question their presence. Many troupes continue to assign female roles to men, either out of custom or due to skill and availability.

Technological and stylistic changes have also reshaped Naman. Traditional instruments like the mridangam, taal, and manjira have been joined, or replaced by dholki, keyboards, electronic pads, and sound systems.

The costumes have evolved from simpler attire to more elaborate and costly outfits.

In earlier times, Naman was performed by locals in their villages, typically around Diwali or Bhat Kapni, to bring the community together and celebrate the prosperity of the year. Today, however, it is carried out by professional artists who have formed Naman Pathaks (groups). These groups now perform throughout the year in various villages, often on special occasions such as the consecration of a newly built Mandir or a Satyanarayan puja.

However, the art form faces mounting challenges. Many artists talk about how modern audiences often favor DJs and orchestras, sidelining traditional theatre. In some cases, performances have leaned toward crude humor or vulgarity, deviating from their original epic and moral focus. Many Shahirs, once central to the creative process, have migrated to cities like Mumbai or Pune, leaving some groups without strong leadership. Performers also face financial instability, lack of social respect, and disruptive audiences. As a result, some have chosen to abandon the tradition altogether.

Yet, despite these challenges, many performers remain deeply committed to Naman. They continue to preserve their storytelling traditions, mentor younger artists, and adapt where needed without losing the form’s core. Perhaps with greater public awareness, institutional backing, and community support, Naman has the potential not only to survive, but to thrive once again as a vital expression of Konkan’s cultural imagination.

Jakadi/Balya - Stories of Shravan during the Mid-Monsoon Respite

Jakadi (also known as Shakti-Tura, Balya, or Chavli Naach) is a traditional folk performance art that is typically performed during the mid-monsoon season. It combines elements of dance, music, and storytelling. The art form holds particular significance during Ganesh Utsav celebrations, when male teenagers from particular villages would visit different houses and perform in their aangans (courtyards) after the evening aartis.

![Jakadi being performed.[3]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ratnagiri/artforms/jakadi-being-performed3-242f4fdc.jpg)

Traditionally, after farming activities were completed during the mid-monsoon period, people would gather at community places like the Gaon Devi Mandir. Men would then dance and sing songs dedicated to various Devis and Devtas, accompanied by the music of Jhanj, Dholki, Taal, and Chaal. This dance was known as Jakadi or Chavli Naach. With the migration of Kokani people to Mumbai, it became known as Balya Naach.

Over time, artists say not only has the name changed, but so have the participants and instruments. While initially performed exclusively by men, women also take part in some places now. The musical instruments have evolved as well; modern performances often incorporate sound systems and smaller dhols alongside traditional Dholkis, Taals, and Jhanj.

During the performance, dancers move in a circle while singers and instrumentalists remain seated inside the circle. The initial songs praised Ganpati, the muse and deva of the art, who is prayed to before any auspicious events in local households. Subsequently, the songs shift to mythological themes, telling stories from the Mahabharat, Ramayan, and Krishna Leela. Popular stories include those of Shravan, Sita-Haran, and Krishna's playful mischief with the gopis in Vrindavan.

A crucial element of Jakadi, similar to Naman, is the role of the Shahirs. Shahirs serve as composers, lyricists, singers, and sometimes instrumentalists, making them the backbone of Kokan's performance arts. They are expected to be deeply religious and well-versed in Hindu religious texts, as they significantly contribute to the performance.

Many district-level competitions have emerged, where groups (pathaks) from various parts of Ratnagiri, often consisting of members from a particular village, compete and win accolades and prizes. Similar competitions are also held for Naman performances.

However, some believe that Jakadi has lost some of its authenticity over time. With many Shahirs migrating out of the district and teenagers losing interest, Jakadi now appears to be more of a ritual performed during Ganpati rather than a lively art form meant for communal enjoyment and togetherness.

Katkhel

Katkhel is a local folk art performance prevalent in the Dapoli region of Konkan. Usually performed by men in a ghagra made out of a Nauvari Saree (9-yard saree), a pink shirt/coat, and a panchangi (a type of turban and veil).

The art form is believed to have originated during the time of Shivaji Maharaj. Katkhel means ‘a game played with the help of sticks’, where Kat means sticks and khel means game. The performers usually belong to the Kunbi and Maratha communities. Notably, in 1982, a performance of the said art form was also performed at the Asian Games in front of then Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi.

A Katkhel performance starts after the performers offer a coconut to the local devi or devta. The performance comprises singing, dancing, intricate formations, and musical instruments such as a taal, manjira, and dholki. The performance comes to an end when the performers do an aarti of the local devi or devta.

Handicraft

Lohar Community of Ratnagiri

The Lohars are traditional metal smiths in Ratnagiri district who have been historically significant for their role in agricultural tool production and metalworking.

Ratnagiri, being a predominantly agricultural district, historically relied heavily on lohars (blacksmiths) for crafting various essential implements such as koytis, metal plates, plough shares, and tools for opening coconuts. Many lohars passed down their skills through generations, and their work was integral to village life, with women also actively participating in these tasks.

However, with the advent of modern technologies, many locals remark on how the role of lohars in the village economy has significantly diminished. Although lohar families can still be seen in the district, metalwork is no longer the primary source of income. Many lohars have been forced to migrate to urban centers, abandon their traditional practice, and take up low-paying jobs. Their economic situation is precarious, and they are often underprivileged. Today, they primarily sell some of their wares during the monsoon and harvest seasons and continue to perform tasks such as sharpening and strengthening koytas. Metalwork is no longer a profitable business for them.

A small cluster of lohar families can still be found in Ratnagiri city, specifically on Juni Tambat lane, near the Hunter Memorial Church.

Cultural Programs

Art Circle Ratnagiri

Art Circle Ratnagiri is a cultural organization based in Ratnagiri, Maharashtra, India. Founded in 2008, it operates from the historic Thiba Palace and organizes various cultural events throughout the year.

Annual Classical Music Festival

The organization's flagship event is a three-day classical music festival held annually during the last weekend of January. Since its inception, the festival has featured performances by over 100 artists from both local and international backgrounds. The festival takes place at Thiba Palace.

![Sane Guruji[5]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ratnagiri/artforms/sane-guruji5-801fe099.png)

Literary Programs

Between 2008 and 2018, the organization hosted the Purushottam Laxman Deshpande literature festival (Pulotsav). This festival celebrated the works of the noted Marathi writer P. L. Deshpande through literary discussions and performances.

Creative Spaces of the District

Devrukh Museum

The Laxmibai Pitre Art Museum, commonly known as the Devrukh Art Museum, is an art museum which is dedicated to the display of artworks curated by artists primarily from Ratnagiri and its surrounding districts. The museum is situated in Devrukh and was established in 2014.

The artworks on display predominantly are said to belong to the ‘Bombay School of Art’ tradition. The Bombay School of Art was a local movement or rather a style that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries - an umbrella term used for early twentieth-century painters from Western India who painted in an academic realist style. Among the highlights of the collection are works by prominent artists such as Pestonji Bomanji, Eruksha Pestonji, Dadiseth Eruksha, and the Haldankar family.

The museum’s collection has its roots in the efforts of Arun V. Athalye, the fourth president of the Devrukh Shikshan Prasarak Mandal, an organization that was formed in 1927. Athalye, worked diligently to preserve the works of local artists, many of which were initially collected by Mulye Master and later donated by his family to the Mandal.

Artists

Bahinabai

Bahinabai was a Marathi poet and bhakt of the Varkari tradition, known for her devotional abhangas composed in the 17th century. Born in a Brahmin family in Devghar, she is regarded as one of the few prominent women voices in Maharashtra’s Bhakti movement.

Her poetry is notable for its introspective and autobiographical tone. Many of her abhangas fall under the category of atma-nivedan, in which she reflects on her spiritual journey across lifetimes. She often explored the tensions between her role as a woman and her pursuit of liberation. In one abhanga, she writes: “I was born with a woman’s body, How am I to attain Truth?”

Unlike many Bhakti poets who distanced themselves from household life, Bahinabai integrated domestic experience into her devotion. Her verses express both longing for Vitthal and a deep engagement with the challenges of spiritual life from within the household.

Today, around 473 of her abhangas survive, 78 of which are considered autobiographical. Her work remains part of the oral and devotional traditions of Maharashtra, especially within the Varkari sect.

Sane Guruji

Pandurang Sadashiv Sane, popularly known as Sane Guruji, was a renowned Marathi author, educator, freedom fighter, and social reformer. Born on December 24, 1899, in Palgad village near Dapoli in the Ratnagiri district, he emerged as a prominent figure in India's struggle for independence and the promotion of social equality

![Sane Guruji[5]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ratnagiri/artforms/sane-guruji5-8b8eaf3c.png)

Sane Guruji's early life was marked by financial hardship, which instilled in him a deep empathy for the underprivileged. He pursued higher education in Marathi and Sanskrit literature, earning his M.A. degree. Choosing a path of service, he became a teacher at Pratap High School in Amalner, where his dedication to students earned him the affectionate title "Guruji" (respected teacher).

Deeply influenced by Mahatma Gandhi's ideals, Sane Guruji actively participated in the Indian independence movement. He was imprisoned multiple times for his involvement in civil disobedience campaigns, including the Salt Satyagraha and the Quit India Movement. During his incarceration, he utilized his time to write extensively, producing literature that inspired and educated the masses.

One of his most celebrated works is "Shyamchi Aai" (Shyam's Mother), an autobiographical novel that pays tribute to his mother's love and teachings. The book remains a classic in Marathi literature and has been translated into several languages.

![Cover of Shyamchi Aai, Sane Guruji’s autobiographical novel, which reflects on his mother’s influence and moral teachings. The book remains a classic in Marathi literature and is widely read across generations.[6]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ratnagiri/artforms/cover-of-shyamchi-aai-sane-gurujis-autobio_ha12UbS.png)

In 1948, Sane Guruji founded the weekly magazine Sadhana, aiming to promote socialist ideals and address social issues. He also initiated the Antar Bharati Movement, promoting national integration through cultural exchange and the learning of multiple Indian languages.

Sane Guruji passed away in 1950 at the age of 51. His legacy endures in Maharashtra through his writings, educational initiatives, and influence on generations of readers and reformers.

Laxman Mahadeo Chitale

Laxman Mahadeo Chitale was a prominent Indian architect known for his contributions to modern architecture in India. He is celebrated for his work in designing several iconic buildings, especially in the mid-20th century. Chitale's architectural style combined modernist principles with elements of traditional Indian architecture, reflecting a deep understanding of local culture, climate, and materials.

One of his most notable contributions was his involvement in the design of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) building in Mumbai, which remains an architectural landmark. He also worked on various urban planning and infrastructure projects, helping shape the architectural landscape of post-independence India.

Dada Salvi

Dada Salvi, born Dinkar Shivram Salvi in Ratnagiri, started his career in theater before transitioning to films in the late 1920s. He gained recognition in both silent and talkie films, with roles in notable movies like "Alam Ara" and "Chhatrapati Sambhaji". Known for his versatility, Salvi worked with major filmmakers and acted in both Hindi and Marathi films. His performances in movies such as "Gajabhau" and "Sawal Majha Aika" earned him wide acclaim. Salvi passed away in Pune, leaving a significant mark on Indian cinema.

Pralhad Anant Dhond

Prahlad Anant Dhond was a renowned Indian painter who was known for his mastery in watercolor landscapes. Dhond’s works often depicted the natural beauty of the Western Ghats, coastal regions, and rural life in India. His paintings captured the essence of monsoons, lush greenery, and the serene countryside.

![Prahlad Anant Dhond[7]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ratnagiri/artforms/prahlad-anant-dhond7-21a58ba7.png)

Dhond served as the principal of the Sir J. J. School of Art in Mumbai and was highly respected for his contributions to Indian art. He was honored with several prestigious awards and has an autobiography called Raapan.

Onkar Bhojane

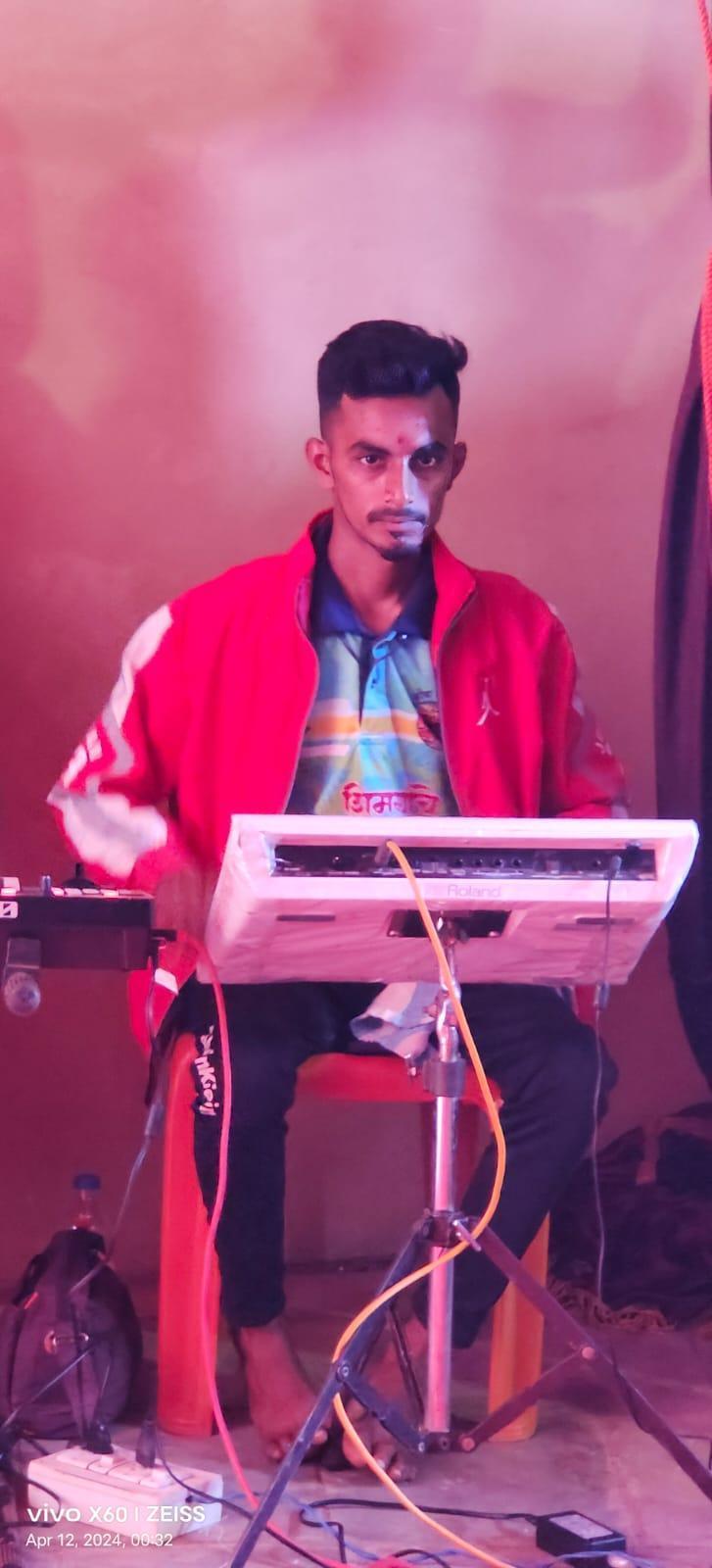

![Onkar Bhojane performing on stage, known for his expressive comic timing and versatility across roles in Marathi film and television.[8]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/ratnagiri/artforms/onkar-bhojane-performing-on-stage-known-fo_wJYx2WE.png)

Onkar Bhojane is a Marathi actor, known for his versatility in playing comedic, serious, and villainous roles. He gained fame through his standout performance on the popular comedy show Maharashtrachi Hasya Jatra, where his comedic timing and engaging acts captivated audiences across Maharashtra. With notable roles in films like Boyz 2 (2018), Girlz (2019), and Sarla Ek Koti (2023), Onkar has established himself as a prominent figure in the Marathi film industry.

Sources

2014. “Thirty years of building in Madras.” The Hindu, April 6, 2014. Accessed May 18, 2025.https://www.thehindu.com/features/metroplus/…

DECAD. “About Devrukh.” Accessed May 18, 2025.https://www.decad.in/aboutdevrukh

Devrukh Museum.“About.” Archived February 13, 2015. Accessed May 18, 2025.https://web.archive.org/web/20150213170257/h…

Disha Ahluwalia. 2024. “Maharashtra’s geoglyphs discovery is citizen archaeology at its best. It put India on the map." ThePrint. Accessed May 18, 2025.https://theprint.in/opinion/maharashtras-geo…

Government of India. “Pandurang Sadashiv Sane.” Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav – Unsung Heroes. Accessed May 18, 2025.https://amritmahotsav.nic.in/unsung-heroes-d…

North Maharashtra University. “About Us – Sane Guruji Shikshan Kul.” Accessed May 18, 2025.https://nmu.ac.in/sgsk/About-Us

Susie Tharu, and Lalita, eds. 1991. Women Writing in India, Volume I: 600 BC to the Early Twentieth Century.New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Wikipedia contributors. “Dada Salvi.” Wikipedia. Accessed May 18, 2025.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dada_Salvi

Wikipedia contributors. “Onkar Bhojane.” Wikipedia. Accessed May 18, 2025.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Onkar_Bhojane

Wikipedia contributors. “Pandurang Sadashiv Sane." Wikipedia. Accessed May 18, 2025.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pandurang_Sada…

Wikipedia contributors. “Pralhad Anant Dhond.” Wikipedia. Accessed May 18, 2025.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pralhad_Anant_…

Last updated on 22 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.