Contents

- Ancient History

- Acheulian Remains near Guhagar

- The Petroglyphs of Ratnagiri

- Megalithic Burial Site at Kumbhavade village

- The Origin Story of Konkan & Chiplun

- Early Buddhist Influence and Trade

- Religious Patronage in the Region

- From the Satavahanas to the Shilaharas

- Pranalaka and the Shilaharas of North Konkan

- Medieval Period

- Dabhol as a Prosperous Trade Center

- Early Adil Shahi Administration and Revenue Settlements (1502)

- The First Portuguese Assaults (1508–1510)

- Portuguese Control and Influence

- Alphonso Mangoes

- Trade Developments

- Maratha Expansion and Administration in Konkan

- Revenue Reforms Under Shivaji Maharaj

- Kanhoji Angre

- Peshwa vs the Angres

- Under the British Raj

- Administrative Changes

- British Revenue System

- Ties to the Early Freedom Movement

- Salt Satyagraha, 1930

- Labour Exploitation

- Dr Ambedkar’s Visit to Ratnagiri

- Quit India Movement

- The Exile of King Thibaw

- Post-Independence

- Political and Administrative Changes

- Recognition of Kokum

- Sources

RATNAGIRI

History

Last updated on 28 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Ratnagiri district, located along the Arabian Sea in the picturesque Konkan region, has a rich and layered history. It is home to ancient petroglyphs, prehistoric rock carvings that offer rare insight into early human life on the western coast of India. Over time, the district came under the rule of major dynasties, who each have left an everlasting mark on the district’s cultural heritage and governance.

This district is home to Dabhol port, which has held a prominent position since ancient times as a major center of trade. It attracted merchants and travelers from distant lands and played a role in the spread of Buddhist ideologies beyond India. Its strategic coastal location facilitated maritime trade routes, which, in many ways, contributed to the district’s prosperity. During the colonial period, Ratnagiri remained under British rule for over two centuries and played a role in the freedom struggle. It was the birthplace of Lokmanya Tilak and a center of influence for leaders like Gopal Krishna Gokhale. For much of its modern administrative history, Ratnagiri included what is now the Sindhudurg district. In 1981, the region was reorganized and Sindhudurg was carved out as a separate district, which in turn, shaped the present boundaries of Ratnagiri.

Ancient History

Acheulian Remains near Guhagar

One of the earliest traces of human presence in Ratnagiri district has been recorded from areas along the coast of Guhagar taluka. In 2001–02, a series of archaeological surveys was undertaken here, focusing on several localities near the villages of Palshet and Hedvi. These efforts sought to investigate the potential for Palaeolithic activity along the Konkan coastline and led to the discovery of three sites linked to what archaeologists call the Acheulian tradition: a style of stone tool-making that stretches back hundreds of thousands of years.

At Susrondi, a small settlement near Palshet, two stone tools (known as cleavers) were found lying on the surface near a shallow cave carved into lateritic rock. Nearby, in Mandakvarkwadi, more stone tools were collected, including choppers and another cleaver, also from surface contexts. A third site at Hedvi revealed animal bones inside a rock shelter. These bones showed clear-cut marks, likely made by stone tools, pointing to early butchery or food processing.

Together, these findings represent the earliest known traces of human occupation along the Konkan coastline. The tools recovered, according to scholar Ashok Mahade (2006), conform to the typology of the Late Acheulian phase and attest to human activity here during the early part of the Late Pleistocene, a period that began around 1,25,000 years ago.

The Petroglyphs of Ratnagiri

Another significant trace of early human presence in the Ratnagiri district comes from its petroglyphs, which are prehistoric rock carvings that are etched into the laterite surfaces of the Konkan plateau. These carvings, often created by chiseling into stone or arranging rock fragments to form shapes, are believed to date back to the Mesolithic period, roughly 10,000 to 12,000 years ago.

While petroglyphs are found across parts of India, the Konkan region has one of the highest concentrations. Within this zone, Ratnagiri stands out for the number and diversity of sites. Villages like Devihasol and Barsu in Rajapur taluka, and Ukshi in Ratnagiri taluka, are among some of the key sites where these carvings have been discovered, with many of them being estimated to be around 10,000 to 12,000 years old. The subject of these carvings has been of much interest over the years, as many of them depict animals and offer insight into the environment and the world of early humans.

It is important to note that the discovery of petroglyphs in the Konkan region is considered highly significant, as it constitutes the first archaeological findings of prehistoric human activity in this coastal area. Today, the petroglyph sites of Ratnagiri are included in UNESCO’s Tentative List of World Heritage Sites. Their age, scale, and the questions they raise about early life in the region continue to draw interest from researchers and conservationists alike.

Megalithic Burial Site at Kumbhavade village

A further glimpse into the district’s prehistoric past has emerged from the recent discovery of Megalithic-era remains near the Gambhireshwar (Gango) Mandir in Kumbhavade village, located in Rajapur taluka. This discovery, made in 2025 by researcher Satish Lalit, is considered highly important, for, as Dhaval Kulkarni (2025) notes, “this is the first time that megalithic-era memorials have been found along the Konkan coastline in the state.”

Among the finds uncovered here are seven 'menhirs,’ which are tall and upright stone pillars. These megalithic monuments are arranged in three distinct clusters near the Mandir. Carved from locally available laterite (jambha stone), five of the menhirs still stand, while two have toppled. Notably, all the structures are oriented along an east–west axis, which may indicate intentional orientation.

Menhirs are a significant element of Megalithic cultures and are typically interpreted as memorials for the dead. Its presence here, in many ways, provides new material evidence of human occupation in the region during the Megalithic period and also extends the known geographic spread of Megalithic practices.

The Origin Story of Konkan & Chiplun

Across centuries, many legends have emerged around the origins of places, including the Konkan region. One particularly fascinating tale is tied to Chiplun, a town that has historically served as a major commercial and trade center in Ratnagiri district. According to local tradition and texts like the Skanda Purana, the city’s origin is tied to the Chitpavan Brahmins, a community said to have been created by Parshuram, the sixth avatar of Vishnu.

The Sahyadri Khanda, which is believed to be a later addition to the Skanda Purana, narrates how Parshuram (regarded as the sixth avatar of Vishnu), in search of purification after his campaign against the Kshatriyas, reclaimed land from the sea, now known as Konkan, and sought Brahmins to perform Vedic rituals on it. The legend claims that he revived fourteen corpses washed ashore after a shipwreck, purifying them on a funeral pyre and bringing them back to life. These resurrected individuals became known as Chitpavan (literally “pure from the pyre”). While epic in tone, the story likely hints at an early maritime migration of Brahmins to the Konkan coast, and the reason why Chiplun is considered to be one of the earliest settlements of this community.

Today, this legacy is reflected in the Parshuram Mandir in Chiplun, believed to have been built in the 18th century, with some sources attributing its construction to Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj.

Early Buddhist Influence and Trade

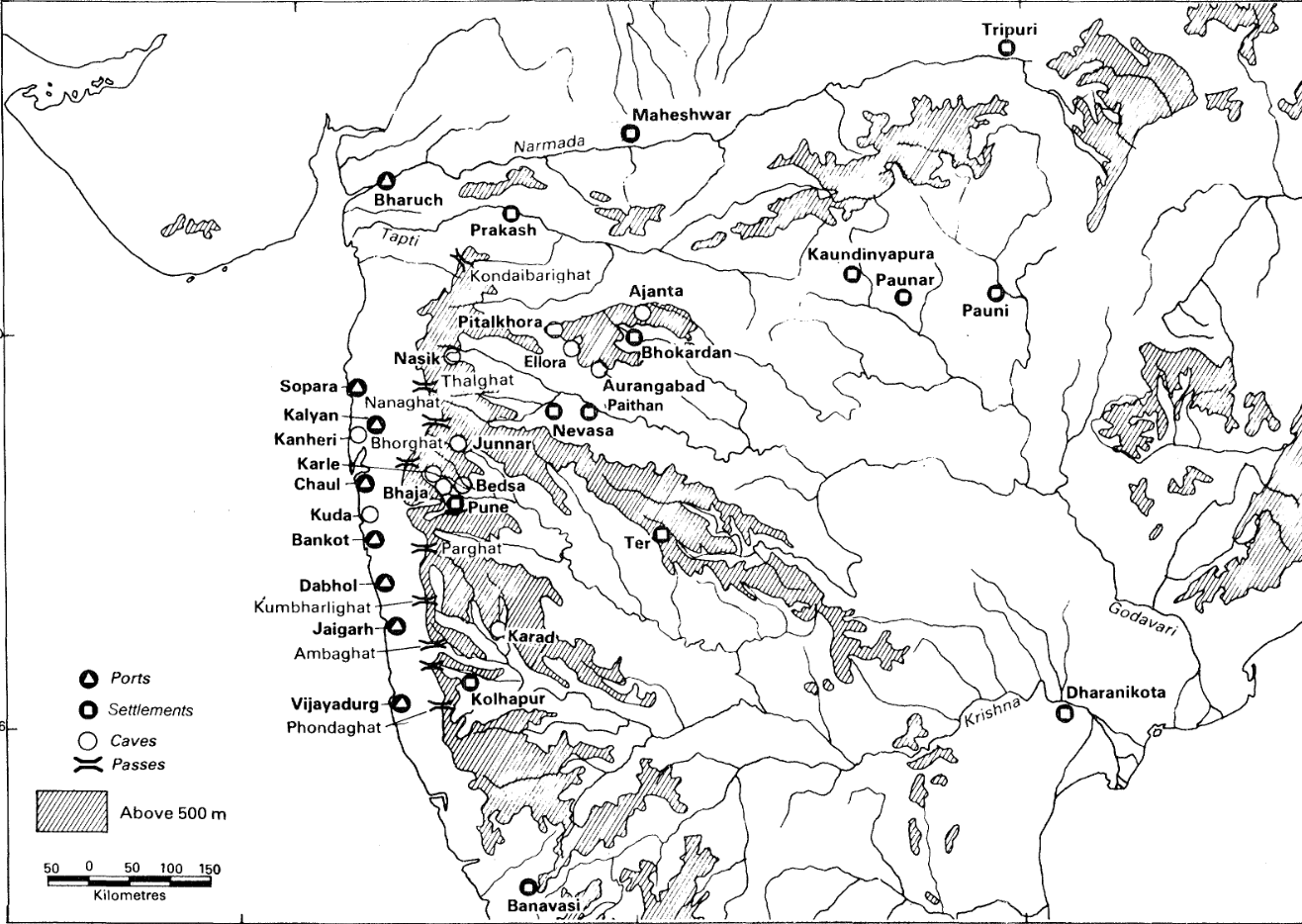

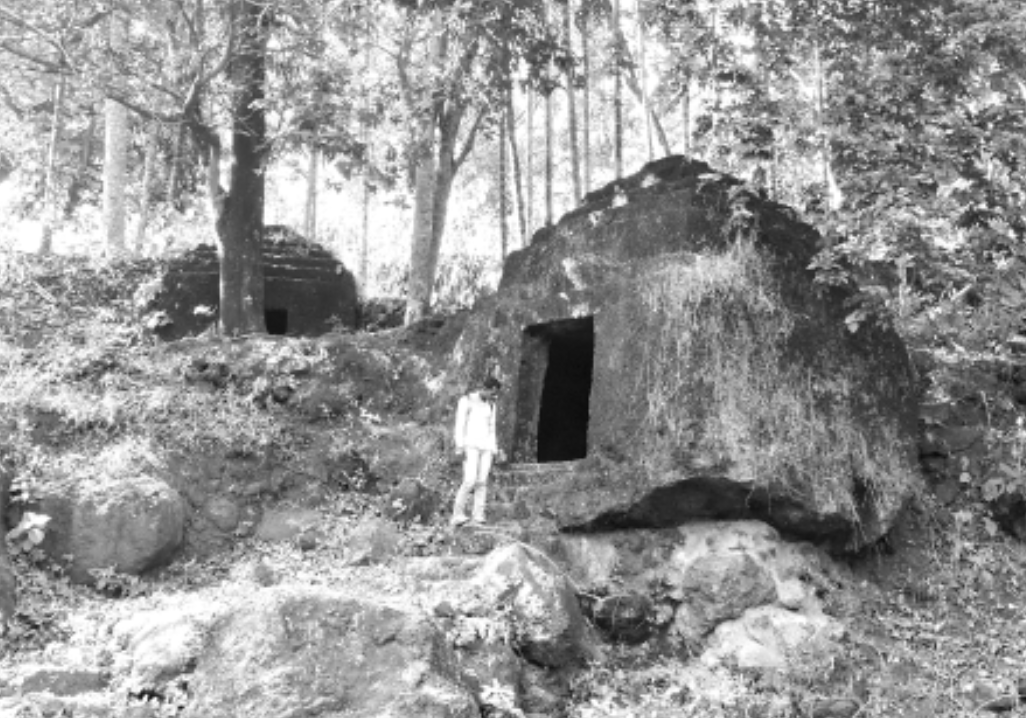

By the 2nd century BCE, it appears that Ratnagiri had begun to draw the attention of traders, monks, and maritime travelers. In towns like Chiplun and Kol, Buddhist rock-cut caves were excavated into the hillsides. While there are no direct records linking specific rulers to these constructions, historical patterns suggest that the Satavahana dynasty, which succeeded the Mauryas in the Deccan and Konkan regions, may have patronized these structures. These were likely used as viharas (monastic quarters) and chaityas (prayer halls), with some caves featuring stupas, sculptures, and inscriptions.

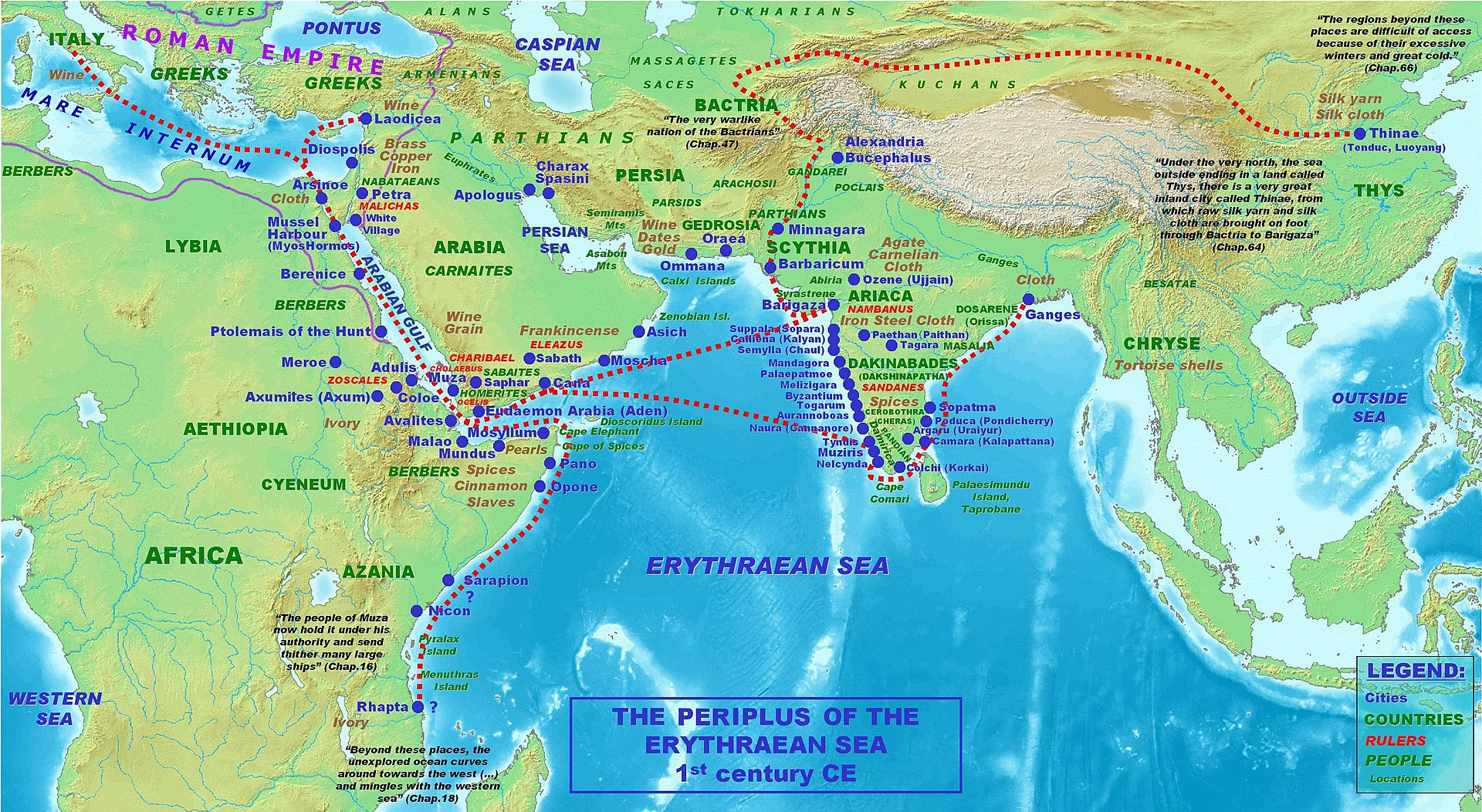

These viharas and chaityas may have provided shelter to monks and merchants traveling along the trade routes, many of which threaded inland through passes like Kumbharli Ghat or connected to coastal ports like Dabhol, Bankot, and Palshet. It is important to note that Ratnagiri district was a prominent trade center during this time, so much so that it is believed that the well-known Greek maritime text, The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (1st century CE), refers to one of these ports. The ancient port of Palaepatmai is generally identified with present-day Palshet, which remained active as a harbor until the seventeenth century.

Religious Patronage in the Region

From the 3rd century CE onwards, Buddhist activity in the Ratnagiri region grew steadily, leaving enduring marks on its landscape. Numerous rock-cut caves attest to this flourishing monastic life, with Panhale Kaji standing as one of the largest and most significant sites. This complex, comprising twenty-nine caves, was first excavated by the Hinayana sect and later expanded under the Vajrayana tradition during the 10th and 11th centuries CE. Inscriptions in early Brahmi and later Devanagari scripts record continuous occupation and reflect the changing nature of religious practice over the centuries. Smaller but noteworthy caves at Chiplun (known as the Panch Pandav Caves) and at Khed further illustrate the extent of Buddhist influence in the district. Notably, M.N. Deshpande (1986), suggests that the mercantile community of Dabhol likely supported both the excavation of these caves and the sustenance of the resident monks.

By the early medieval period, Jainism had likewise established a presence in Ratnagiri. While its influence during the Satavahana era remains uncertain, by the 10th century CE, Jain communities were sufficiently prominent to leave behind sculptures of Tirthankaras, remains of Mandirs, and monolithic shrines, found notably at Konzar and Dabhol. The colonial district Gazetteer (1880) mentions that during the medieval period, Jainism held the status of a state religion in parts of the district.

From the Satavahanas to the Shilaharas

Following the Satavahana decline, Ratnagiri likely fell under the Western Kshatrapas, particularly during the reign of Rudradaman I (c. 130–150 CE), whose conquests are noted to have extended across Gujarat, Malwa, and coastal Konkan. Their influence persisted until about the early 5th century, when the Mauryas of Konkan appear to have filled the vacuum.

According to the Gazetteer (1880), by the 6th century, the Chalukyas of Badami had extended their reach into southern Ratnagiri, gradually pushing out the local Mauryas by 634 CE. This may suggest that both dynasties may have coexisted for a period before Chalukyan control was firmly established.

In the 9th century, the Rathods of Hyderabad briefly held power before the emergence of the Shilahara dynasty, who had been feudatories of the Rashtrakutas. The Shilaharas governed Konkan through three branches:

- North Konkan

- Kolhapur–Satara region

- Sapata-Konkana (South Konkan, including modern Goa and parts of Ratnagiri)

The Sapata-Konkana branch ruled from about 765 CE to 1020 CE. Following their decline, copperplate inscriptions from around 1070 CE show that the North Konkan Shilaharas extended their control over the region.

Pranalaka and the Shilaharas of North Konkan

The significance of Panhale-Kaji (briefly mentioned above), interestingly, grows during this later Shilahara phase. MN Deshpande (1986), in his ASI report, notes that the village is mentioned in two 12th-century Shilahara inscriptions as Pranalaka.

One, published by Dr. Shobhana Gokhale in Itihasa ani Samskriti (vol. XXIX), refers to a copperplate grant dated 9 October 1139 CE (Saka 1061). Issued by Aparaditya I, the grant bestows the village of Khairadi, located in the visaya of Pranalaka, to a Brahmin named Rudrabhattopadhyaya from Varanasi.

A second inscription from 1156 CE (Saka 1078) records the appointment of Supraya as the dandadhipati (administrator) of Pranalaka desha, with a directive to make Pranala his capital. Despande writes, “it is also stipulated that his oldest son should succeed him and make the same city his headquarters,” suggesting the administrative importance of the site.

From these inscriptions, Deshpande mentions that it appears that Vikramaditya, a favored son of Aparaditya I, was appointed around 1138 CE to govern southern Konkan with Pranalaka as his capital. After Aparaditya’s death, his son Haripaladeva likely took over North Konkan, while Vikramaditya continued to rule the south. No successors of Vikramaditya are known, and it is believed that Haripaladeva eventually reunited both regions under his rule.

Later, as the Rashtrakuta Empire waned, the Konkan region saw the rise of various smaller kingdoms. Amid this fragmentation, Ratnagiri experienced both the economic impact of trade and the social consequences of political instability. Frequent changes in rulership from the 12th to 14th centuries likely disrupted local governance and patronage in the region.

Medieval Period

In the early 14th century, the district fell under the dominion of the Delhi Sultanate, which marked a significant shift in its political history. According to the Gazetteer (1880), when the Bahmanis established their independence in 1347, South Konkan became its natural seaboard, with Dabhol emerging as one of their notable strongholds. However, the inland areas of the district remained largely unconquered, likely due to their perceived lack of economic significance until the final years of their reign. The Gazetteer further notes that even during the Bahamani era, certain parts of the district maintained allegiance to the Vijayanagar Empire, and the hold of the Deccan Sultanates was rather slight.

As the Bahmani Empire fragmented in the late 15th century, especially after the death of its famed prime minister Mahmud Gawan, powerful successor states like the Adil Shahi dynasty of Bijapur and the Nizam Shahis of Ahmadnagar emerged.

These new powers competed fiercely over the Konkan coastline:

- Northern Ratnagiri (near present-day Bankot) fell under Nizam Shahi rule.

- Southern Ratnagiri, including Dabhol, came under the Adil Shahis.

Dabhol as a Prosperous Trade Center

During this period, Dabhol emerged as a principal port on the Konkan coast. The District Gazetteer (1962) describes its prosperity in detail, with the Russian traveller Afanasy Nikitin observing in the late 15th century that, “the horses from Mysore, Arabia, Khorasan and Nighostan were brought here for trade. This was the place that had links with all major ports from India to Ethiopia.”

Despite conflicts in the hinterland, Dabhol remained an active centre of trade throughout the 15th century. Its prosperity, however, drew the attention of the Portuguese, who, seeking to control the Konkan trade, bombarded and sacked the port in December 1508. Though the fort withstood their assault, this marked the beginning of repeated Portuguese attempts to secure Dabhol.

Early Adil Shahi Administration and Revenue Settlements (1502)

As Dabhol flourished, Yusuf Adil Shah strengthened his hold over the coastal region. In 1502, he implemented the first recorded land revenue settlement for Ratnagiri. The system combined remnants of the Vijayanagar model with new measures: old revenue officers were retained, and a new class called khots was introduced in central Ratnagiri. These khots acted as revenue farmers and village headmen. Rice lands were taxed at one-sixth of the gross produce, usually in kind; hill lands (varkas or bharad) were taxed per plough (nangar). Waste lands were granted to officers to lease to settlers, and village communities paid light taxes with no extra cesses (sayar), creating a relatively simple system.

The First Portuguese Assaults (1508–1510)

By the early 16th century, the flourishing port of Dabhol attracted the keen interest of the Portuguese, who were determined to dominate maritime trade along the Konkan coast. Don Lorenzo de Almeida, the Portuguese commander, wrote about Dabhol with clear admiration, showing how highly he valued the port. He described Dabhol as “one of the most noted coast towns with a considerable trade and stately and magnificent buildings, girt with a wall, surrounded by country houses and fortified by a strong castle garrisoned by 6,000 men of whom 500 were Turks.”

Based on their records indicate that Dabhol’s prominence made it a port of considerable interest to them, prompting their determined efforts to secure it. This interest led to the first attack on Dabhol in 1508 CE, which resulted in its eventual capture from the Adil Shahi dynasty in 1510 CE. In response, the Adil Shahis took measures to strengthen the town’s defences. Notably, they constructed the fort of Suvarnadurg near Harnai port to guard against threats from European colonial powers and rival local chiefs. In the 17th century, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, the Peshwas, and the Angrias further improved and reinforced these coastal forts to ensure the continued protection of trade routes and maritime settlements.

Portuguese Control and Influence

Following their initial conquest, the Portuguese maintained a presence at Dabhol and by 1535 had established a factory there. However, the port remained a site of frequent conflict, with repeated Adil Shahi attacks and tensions with other European powers. Portuguese naval expeditions targeted key ports and trade routes along the Konkan coast, seeking to control the region’s maritime commerce. These conflicts often disrupted local trade and strained relations with other ruling powers.

According to the district’s Gazetteer (1962), despite the ongoing conflicts between the Bijapur Sultanate and the Portuguese in the district, the overall administration remained relatively stable during the 16th and the first half of the 17th century. This stability can be attributed in part to the efforts of Yusuf Adil Shah, who took measures to support the development of the district.

Alphonso Mangoes

Perhaps one of the most enduring legacies of Portuguese influence in the Konkan region is the cultivation of the Alphonso mango. Named after Afonso de Albuquerque, the Portuguese general and administrator, this mango variety was introduced through grafting techniques brought by the Portuguese in the early 16th century.

The favourable coastal climate and soil of Ratnagiri allowed the Alphonso mango, locally called Hapus, to thrive. By the 17th century, it had become an important crop in the region and developed a reputation for its distinctive sweetness, aroma, and smooth texture. Over time, the Ratnagiri Alphonso gained recognition beyond local markets and is now regarded as one of India’s finest mango varieties, exported widely and protected under a Geographical Indication (GI) tag.

Trade Developments

In the early 17th century, European powers began competing for trading rights along the Konkan coast. The British made initial attempts to set up a trading factory at Dabhol but met resistance from the Portuguese, who had already established control over several coastal ports. By around 1638, the British succeeded in setting up a factory at Rajapur in Ratnagiri district, which served as a convenient entry point for trade with the cities of the Deccan. The French also opened a factory at Rajapur to benefit from the area’s commercial links. However, both the British and French outposts were frequently attacked and plundered by the Marathas, who by this time had started to consolidate control over coastal and inland trade routes.

Maratha Expansion and Administration in Konkan

By the mid-17th century, the Maratha Empire, under Chhatrapati Shivaji, began expanding along the Konkan coast. Around 1658 CE, Shivaji initiated campaigns that consolidated Maratha control over much of South Konkan. To secure maritime trade and protect coastal settlements, he ordered the construction and repair of forts along the shoreline. According to historical accounts, except for Malvan, which was controlled by the Sawantwadi Rajas (See Sindhudurg for more), Shivaji extended his authority over most of the coastal region. After Shivaji died in 1680, there were many conflicts between the Mughals, the Portuguese, local Maratha commanders, and the Siddis, which took place in the district.

Revenue Reforms Under Shivaji Maharaj

Between 1670 and 1680, when Shivaji briefly brought the Ratnagiri region under his control, he introduced significant reforms to the Maratha revenue system. According to the Gazetteer (1880), these reforms built upon the revenue methods earlier developed by Malik Ambar in the Deccan during the early 17th century. Shivaji’s policy was first carried out by Dadaji Konddev and later refined by Annaji Dattu, aiming to create a stable source of income for the state.

The policy was first carried out by Dadaji Konddev and later refined by Annaji Dattu, with the main goal of creating a stable and predictable source of income for the state.

A key feature of this system was the precise measurement of farmland, especially rice fields. Officials used a standard rod that measured about the length from a person’s elbow to the tip of the middle finger (known as a cubit) plus five “fists” (each fist was roughly four inches or about 10 cm). The measured land was then divided into units called bighas, with each bigha covering about 4,014 square yards, which is roughly the size of a small sports field.

Land was then classified into twelve categories based on how fertile it was. These fell into three broad types: rice lands, hill lands, and garden lands. The government claimed 40% (or two-fifths) of the total produce as its share.

To set fair tax amounts, officials checked how much crop the land typically produced. The harvest was measured in bushels, which is an old unit for measuring grain and other crops: roughly equal to 35 litres in modern terms. On the most fertile land, the standard tax was based on an expected harvest of about 57½ bushels per acre; on poorer land, it was about 23 bushels per acre.

For hill land, the tax was calculated according to how many ploughs worked the land, with adjustments made for rocky or unproductive patches. Garden lands, which used to pay a fixed fee (called kamal), were now taxed by dividing the actual harvest evenly with the government.

Kanhoji Angre

After Shivaji’s death in 1680, his son Sambhaji succeeded him. During Sambhaji’s reign, Kanhoji Angre rose to prominence as the chief of the Maratha navy. From 1698, Angre defended the Konkan coast against European colonial powers and other rivals. Leading the Maratha fleet, he launched repeated attacks on English and Portuguese ships attempting to dominate local ports.

The Gazetteer (1880) records how Angre built and fortified several forts along the coast to secure his naval power. One notable fort connected to him is the Purnagad Fort. It is believed that he constructed the fort likely to protect the region from foreign navies. The fort served as a base for defending and controlling maritime trade routes and launching raids against enemy ships.

His legacy remains significant in Indian naval history. Notably, the Western Naval Command headquarters in Mumbai, INS Angre, is named after him. A port in Ratnagiri district also bears his name, recognising his impact on the region’s maritime history.

Peshwa vs the Angres

After the death of Kanhoji Angre in 1728, one of his sons, Tulaji Angre, assumed control over the territory spanning from present-day Bankot in Raigad to Sawantwadi in Sindhudurg around 1745. During this period, the Maratha Empire's political structure had changed, with the title of Peshwa under Shahuji becoming the highest hereditary post. Tulaji, ruling over Raigad, Ratnagiri, and Sindhudurg, disregarded the authority of the Peshwa, perhaps to maintain his independence. In response, according to the Gazetteer (1880), the Peshwa allied with the British to suppress Tulaji’s power. By 1755, the Peshwa’s forces, with British help, annexed all forts north of present-day Vijaydurg, including key sites in Ratnagiri. This marked the end of the Angre family’s independent naval rule and brought the coastal forts firmly under the Maratha state, which would soon come under British control.

Despite these changes, conflicts continued as neighbouring powers such as the Malvas of Kolhapur and the Savants of Sawantwadi opposed British moves in the region’s ports. By the early 19th century, the entire Konkan coast, including Ratnagiri, came under British control.

Under the British Raj

Administrative Changes

During the first half of the 19th century, the administrative structure of Ratnagiri district was subject to several changes under British rule. Initially, it comprised nine subdivisions. However, in 1830, it was downgraded to the rank of a sub-collectorate. However, this demotion was short-lived, and by 1832, the region was re-designated as a collectorate (district), now comprising five subdivisions.

Further administrative modifications occurred in 1868 when the political boundary of the district was expanded. At that time, Ratnagiri district came to include eight primary subdivisions: Dapoli, Chiplun, Guhagar, Sangameshvar, Ratnagiri, Rajapur, Devgad, and Malvan, alongside four smaller administrative units, referred to as petty divisions: Mandangad, Khed, Lanje, and Vengurla. These petty divisions were administered under the jurisdiction of magistrates' courts, reflecting a tiered system of colonial governance. These administrative changes were part of the broader restructuring of governance systems implemented during the British Raj.

British Revenue System

Significant changes were also made to how land revenue was collected in the district. One of the most debated systems introduced under colonial administration was the khoti system, which became widespread after the Khot Act of 1880. Under this system, a khot was recognised as a middle-level landlord who held superior rights over village land and acted as an agent of the government for collecting taxes.

The khots collected revenue from tenant farmers and passed a share to the colonial state, but they also kept a portion for themselves. In practice, this gave them considerable power over tenant families, who depended on the land for their livelihood. Typically, tenants paid the khot through fixed payments called jama, which covered the official tax (dada) as well as the khot’s own share of the harvest (baha nakt). This grain rent was usually fixed at rates lower than the market price and then converted into cash by the Collector’s office every year.

Although the government sometimes offered special leases (kaul) for projects like reclaiming swamps or dunes, these benefits rarely reached ordinary tenants or khots. Instead, the system allowed the khots to maintain control and extract extra dues from poorer cultivators, especially from communities like the Kunbis, Bhandaris, Mahars (Dalits), and other marginalised groups. Growing resentment against this system would later play an important role in local movements for farmers’ rights and land reform and eventually find wider support during India’s freedom movement, drawing the attention of leaders like Dr B. R. Ambedkar (see more below).

Ties to the Early Freedom Movement

The district has a long association with India’s early nationalist movement and was home to leaders who played key roles in shaping its direction. Among them, Gopal Krishna Gokhale was known for his work in social reform and his opposition to caste barriers. He supported gradual self-government and encouraged public service through the Servants of India Society, which he founded in 1905. To share his views and promote debate, he also launched The Hitavada, an English weekly newspaper. Gokhale is often remembered as an important mentor to Mahatma Gandhi during the formative years of the freedom movement.

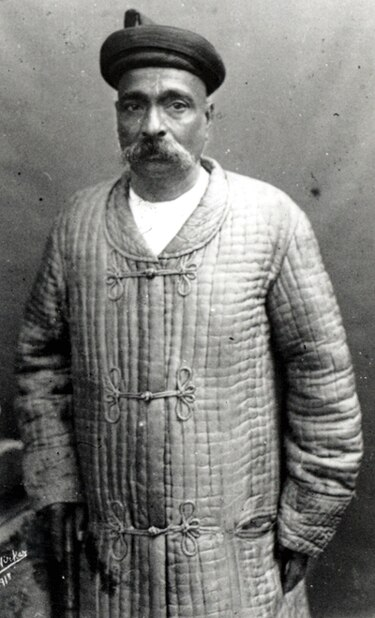

Another key figure from the district was Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who played an early and influential role in the demand for Swaraj, or self-rule. He encouraged the use of local festivals such as Ganesh Chaturthi as opportunities for community gathering and political discussion. He also promoted the legacy of Shivaji to strengthen regional identity and unity. Tilak helped establish organisations that supported education, print media, and civic action, leaving a mark on the early national movement.

Salt Satyagraha, 1930

Ratnagiri district also saw strong participation during the Civil Disobedience Movement. In 1930, local leaders and volunteers joined the Salt Satyagraha. Volunteers travelled from village to village, teaching people how to make salt in defiance of the colonial salt tax. Over forty meetings were held across the district to encourage local participation, leading to numerous local salt marches. One of the most significant satyagrahas in the region took place at Shiroda, which at that time was part of Ratnagiri.

Labour Exploitation

Under British rule, Ratnagiri’s agriculture and local economy suffered due to policies of resource extraction and neglect. Author Manorama Savur (1982) contends that, upon Ratnagiri falling under British control, its agriculture suffered significant degradation within a short period of time. This decline is attributed to rampant deforestation and the exploitation of labor. Additionally, the two primary sectors of the district’s economy (namely, the manufacture of salt and local artisan industry) either received minimal encouragement or were subjected to government monopolies.

Moreover, through a deliberate policy of uneven development, the British effectively relegated the district to a status of reserve labor force. This strategy ensured that the region served as a ready pool of labor for the benefit of the Indian ruling classes. Consequently, Ratnagiri's economic potential was stifled, and its inhabitants were subjected to exploitation and marginalization under British colonial rule.

Dr Ambedkar’s Visit to Ratnagiri

By the 1930s, frustration with the khoti system (which is mentioned above) and broader exploitation had become part of the national conversation. In 1937, Dr B. R. Ambedkar introduced a bill in the Bombay Legislative Assembly calling for the abolition of the khoti system. His visit to Ratnagiri in 1938 energised local campaigns, with leaders like Tanaji Mahadev Gudekar and Sambhaji Tukaram Gaikwad mobilising farmers through groups such as the Ratnagiri Zilla Shetkari Parishad and the Chiplun Shetkari Parishad. Despite these efforts, the khoti system continued until it was finally abolished in Maharashtra in 1950.

Quit India Movement

After the Quit India Movement was declared in 1942, people in the district became active participants in the campaign against British rule. To contain the protests, the British administration arrested senior Congress leaders early on. These arrests led to widespread resentment across the region.

In several parts of the district, residents took steps to disrupt official communication by cutting post and telegraph wires. Some groups also damaged government buildings and other facilities. In Malvan (now part of Sindhudurg), protesters set fire to the taluka office and the treasury, which resulted in financial losses for the colonial administration estimated at several lakh rupees. Such events illustrate how the district contributed to the larger Quit India Movement and remained connected to the final stages of India’s independence struggle.

The Exile of King Thibaw

One of the more unusual episodes in Ratnagiri’s colonial history comes from its role as the place of exile for King Thibaw Min, the last king of Burma. After the British annexed Upper Burma following the Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885, they decided to keep the deposed monarch far from his homeland to prevent any unrest.

In April 1886, King Thibaw, his queen Supayalat, and their daughters were brought to Ratnagiri, where a 30-room residence (now known as Thibaw Palace) was built for them. Though grand in size, life in the palace was marked by isolation and strict oversight. The exiled royal family faced financial hardships, and it is said that the king had to sell his prized Burmese rubies to maintain the household. King Thibaw remained in Ratnagiri until his death in 1916, leaving behind a lesser-known yet enduring link between the district and Southeast Asian history.

Post-Independence

Political and Administrative Changes

With India gaining independence from British rule in 1947, Ratnagiri, along with other princely states and regions, became part of the Indian Union. This transition from colonial rule to independent governance marked a significant political shift, with the district coming under the jurisdiction of the Indian government. It was made part of the New Bombay State until the State Reorganisation took place.

In 1960, the state of Bombay underwent significant changes, leading to the creation of linguistic states such as Maharashtra and Gujarat. As a result, Ratnagiri, which was previously under the Bombay Presidency, became a district within the newly formed state of Maharashtra. In 1981, the southern portion of the district was separated to form Sindhudurg district.

Recognition of Kokum

In recent decades, the region’s traditional produce has gained national recognition. In 2016, ‘Sindhudurg and Ratnagiri Kokum’ received Geographical Indication (GI) status from the Geographical Indications Registry of India. This certification acknowledges that Kokum grown in this part of the Konkan coast has unique qualities linked to its place of origin and traditional methods of cultivation and processing.

Kokum holds an important place in the local diet and culture; it is widely used in sol kadhi (a refreshing drink), curries, and sherbets. Historical records show that during the mid-19th century, Kokum was already being exported from Malvan under the rule of the Sawant Rajas. According to the District Gazetteer (1880), Kokum from Malvan was shipped to other Konkan ports, showing its long-standing economic value to the region.

Sources

Anjay Dhanawade. 2018. Jainism In South Konkan. Vol. 78. Vice Chancellor, Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute (Deemed University), Pune.https://www.jstor.org/stable/26914994?seq=6

Ashok Marathe. 2004-5. Contribution Of The Deccan College To The Study Of Prehistoric And Historical Archaeology Of Konkan. Vol. 64 no. 65. Vice Chancellor, Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute (Deemed University), Pune.https://www.jstor.org/stable/42930632?seq=4

Ashok Marathe. 2006. "Acheulian Cave at Susrondi, Konkan, Maharashtra." Vol. 90, no. 11, Current Science.https://www.jstor.org/stable/24091832

B.S. Shastry. 1987. Commercial Policy of the Portuguese Vis-a-Vis The Adil Shahis of Bijapur in the Seventeenth Century A.D. Vol. 48. Indian History Congress.https://www.jstor.org/stable/44141772?seq=7

Dhaval Kulkarni. 2025. How a Menhir Site May Shed Light on a Dark Phase of Maharashtra’s History. India Today.https://www.indiatoday.in/india-today-insigh…

Himanshu Prabha Ray. 1987. Early Historical Urbanization: The Case of the Western Deccan. Vol. 19, no. 1. World Archaeology.https://www.jstor.org/stable/124501?seq=1

James M. Cambell. ed. 1880. Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency vol. X. Ratnagiri and Savantvadi. Government Central Press, Bombay.

Kushal Choudhary. 2022. #MayDay: Ambedkar and The Anti-Khoti Movement. Medium.https://dalithistorymonth.medium.com/mayday-…

LHI Team. 2018. Ratnagiri and the Last King of Burma. Peepul Tree.https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindi…

M.N Deshpande. 1986. The Caves of Panhāle-Kāji. Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi.https://ignca.gov.in/Asi_data/73737.pdf

Manorama Savur. 1982. Ratnagiri - Underdevelopment Of An Area Of Reserve Labour Force. Vol. 31, no. 2. Sociological Bulletin.https://www.jstor.org/stable/23619869?seq=22

Mrityunjay Bose. 2023. Geoglyphs of Konkan come to focus. Deccan Herald.https://www.deccanherald.com/india/geoglyphs…

N.T. Monc, P.M.Joshi, et al. 1962. Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Ratnagiri District. Bombay, Government Printing, Stationery and Publications.

Tilok Thakuria. 2017. Society and Economy during Early Historic Period in Maharashtra: An Archaeological Perspective. Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology.http://www.heritageuniversityofkerala.com/Jo…

Websites Referred: Ratnagiri District: Official Website, Wikipedia,. Indiastat Districts,Brief History of Chitpavans. Nasik Chitvapan.https://www.indiastatdistricts.com/maharasht…

Last updated on 28 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.