SINDHUDURG

Architecture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Architecture of Prominent Sites

Sindhudurg’s architecture reflects a layered heritage shaped by dynastic patronage, coastal defense strategies, and enduring devotional practices. The Kunkeshwar Mandir, built in the 12th century in Dravidian style by the Yadavas and later supported by the Marathas, stands as a major Shiv Mandir along the Konkan coast, merging spiritual significance with seafront architectural presence. Vijaydurg and Sindhudurg Forts embody the region’s maritime and military legacy: fortified coastal bastions designed to resist naval invasions, with complex defense systems, civic planning, and embedded places of worship that highlight the Maratha Empire’s strategic and cultural vision. In contrast, the 14th-century Lakshminarayan Mandir at Walaval showcases Hemadpanti architectural traditions in teakwood, representing local craftsmanship and evolving religious life in rural Konkan. Together, these sites reveal how dynastic shifts, maritime priorities, and regional religious practices shaped Sindhudurg’s built environment.

Kunkeshwar Mandir

The Kunkeshwar Mandir in Sindhudurg district follows the Dravidian architectural style and was built in 1100 C.E. by the Yadava dynasty. Located in the coastal village of Kunkeshwar, about 14 km from Devgad, it is a prominent Shiv Mandir in the Konkan region.

The Mandir is known as the “Kashi of South Konkan” and draws thousands of people, especially during the Mahashivratri festival. It has been renovated multiple times, with historical records indicating that Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj visited and supported its upkeep. The Mandir’s location on a hillock near the Arabian Sea, with a long white-sand beach below, adds to its striking presence.

The Mandir complex includes a main garbhagriha (sanctum) with a shikhara, pillared mandaps (halls), and intricately carved stone walls. Its coastal placement and architectural form reflect a fusion of regional craftsmanship and spiritual significance.

Vijaydurg Fort

Vijaydurg, historically known as Gheria, is a coastal fort located at the mouth of the Vaghotan River, between the present-day Ratnagiri and Sindhudurg districts. It is believed that the site was originally constructed between 1196 and 1206 CE by Raja Bhoja II of the Shilahara dynasty. In 1653, the fort was captured by Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj from the Adilshahi Sultanate of Bijapur, under Ali Adil Shah II. It was subsequently renamed Vijaydurg, from the Sanskrit “vijay” meaning victory, signifying its role as a strategic conquest.

![Vijaydurg Fort, a key stronghold of the Maratha navy along the Konkan coast, with laterite walls rising from the Vaghotan Creek.[1]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/sindhudurg/architecture/vijaydurg-fort-a-key-stronghold-of-th_duilElR.png)

Vijaydurg is considered the largest fort on the Konkan coast and occupies a naturally defensible site surrounded by the sea on three sides. Its outer wall, built from laterite and rising 10 metres high, extends nearly 300 ft. into the Arabian Sea. The fort is encircled by a 40-km-long creek that prevents large ships from approaching, making it difficult to breach. Its triple-layered fortification system was designed to absorb cannon fire, while strategically placed bastions and watchtowers offered comprehensive surveillance and defense.

The inner fort includes several structures of architectural and historical interest. These include a khalbat-khana (secret meeting room), an ammunition depot, Kanhoji Angre’s courthouse, and a tunnel believed to serve as an escape route. A stone-built Rani Mahal, freshwater tank, two-storied warehouse, and soundproof council hall showcase the fort's planning for prolonged sieges. Religious features include a Mandir dedicated to Devi Bhavani, the kuldevi for several Maratha families. Excavations have also uncovered large submerged stone barriers off the western side, thought to be underwater defenses designed to deter ships.

Vijaydurg spans 17 acres and continues to stand as a testament to Maratha maritime strength and architectural ingenuity. Restoration efforts led by the Archaeological Survey of India aim to preserve the structure while promoting sustainable tourism.

Lakshminarayan Mandir

The Lakshminarayan Mandir in Walaval village, Kudal taluka, follows the Hemadpanthi architectural style and was built in the 14th century. It is one of the few mandirs in the region constructed almost entirely from teakwood, making it architecturally unique.

The Mandir has an east-facing orientation and features a spacious sabhamandap (assembly hall) used for religious events like bhajans, kirtans, and Dashavtar performances. The wooden structure is supported by intricately carved stone and teakwood pillars, each showcasing detailed, individual craftsmanship. The inner garbhagriha has a beautifully carved low door with lotus motifs, leading to the murti of Lakshminarayan.

The Mandir is known for its serene environment and is surrounded by lush natural beauty. A large bell inside the Mandir, believed to have been taken from Portuguese sailors, is inscribed in French. Every year on Dwadashi, a procession carrying the Palkhi of Shri Lakshminarayan travels to the nearby Mauli Mandir, demonstrating a visit to his sister, Mauli Devi.

Sindhudurg Fort

Sindhudurg Fort, believed to have been built between 1664 and 1667 by Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, follows a coastal military architectural style and stands on Kurte Island off the Malvan coast in Sindhudurg district. The fort served as the naval headquarters of the Maratha Empire and remains one of the most significant maritime forts in India.

![Sindhudurg Fort, built by Shivaji Maharaj in the 17th century, showcases coastal military architecture on Kurte Island in the Arabian Sea.[2]](/media/culture/images/maharashtra/sindhudurg/architecture/sindhudurg-fort-built-by-shivaji-maha_bXO3viy.png)

The name ‘Sindhudurg’ combines the words Sindhu (sea) and Durg (fort), referring to its strategic location in the Arabian Sea. The fort spans 48 acres and is fortified by 29-ft-high, 12-ft-thick walls that stretch over two miles and are reinforced by 52 bastions. It is believed that over 3,000 workers were involved in the construction of the fort.

The Dilli Darwaja, the main entrance, is ingeniously camouflaged within the surrounding walls, making it hard to spot from the sea. Within the fort are several freshwater wells and secret passageways, showcasing advanced medieval engineering adapted to a maritime setting. The fort also contains several mandirs, including the Shivrajeshwar Mandir, the only known Mandir dedicated to Shivaji Maharaj within a fort, as well as mandirs for Hanuman, Bhavani, and Mahadeo.

Sindhudurg Fort is not only a measure of naval strength but also of architectural ingenuity and cultural resilience.

Residential Architecture

In Sindhudurg, the architecture of homes tells so many story. Each structure carries the imprint of local history, community life, and a distinctive cultural identity of the district’s many inhabitants. They also carry within them the traditions and ways of living of the time they were built in.

The 18th-Century Royal Residence of the Sawant Bhonsles

Royal families throughout history have left their mark through various accomplishments: military conquests, civic works, and architectural commissions. Among these legacies, perhaps none offers a more intimate glimpse into royal life than the palaces they inhabited. These structures, in many ways, not only offer a glimpse into their personal lives and tastes but also the distinctive architectural styles of their dynasties and eras they belonged to.

In the coastal town of Sawantwadi, the legacy of the Sawant Bhonsle dynasty finds expression through one such enduring structure. Located at the base of Narendra Hill, this two-storey laterite stone palace was constructed during the reign of Khem Sawant III (1755–1803). It served not only as a royal residence but also as the administrative seat of the Sawant Bhonsle rulers, and continues to stand as a testament to their political and cultural influence in the region.

The Sawantwadi State was founded in 1627 by Khem Sawant I. Over the centuries, the rulers of Sawantwadi strategically positioned themselves between larger political powers, including the Portuguese in Goa, the Marathas, and later the British. During colonial rule, Sawantwadi became a princely state which maintained semi-autonomy, and the palace continued to serve as the center of governance until India's independence in 1947.

The origins of the palace are tied to a significant shift in the dynasty's approach to governance. While the Sawant Bhonsle capital was originally rooted in the fortified hilltop site of Juna Kot, Khem Sawant III orchestrated a move to the base of Narendra Hill. This transition marked a shift away from defensive architecture toward a more accessible and administrative residence. Over the following decades, additions were made to the complex, most notably the construction of Moti Talav in 1874, a large man-made lake that lies directly in front of the palace. Together with the surrounding gardens and coconut groves, it continues to define the character of the palace grounds.

The architectural language of the Sawantwadi Palace, very interestingly, reflects the layered political and cultural context of the region. The building follows a square plan centered around an open courtyard, with rooms arranged on all four sides, drawing from the wada-style domestic architecture seen across Maharashtra. The use of laterite stone, locally known as chira and widely available in the region, highlights how local materials and environmental context shaped construction choices.

The architectural character of the palace also reflects a mix of influences that came in over time. While the overall structure follows local building traditions, elements like English-style arches along the facades point to the presence of Portuguese and British styles, reflecting the expanding colonial presence and its influence on the region’s architectural vocabulary.

One of the clearest examples is the Lester Gate, believed to have been built in 1895. Made from the same red laterite, the gate stands out with its twin towers, a large central arch, and domed tops. White plaster outlines and neat corner blocks (called quoining) break up the red stone, while surface detailing adds a layer of ornament. Its design language is a mix of European and local forms.

The entrance to the palace itself continues this blend. A tall, tower-like structure anchors the front. At its base is a pointed arch, above it a round window (oculus), and between them, a small balcony with a railing, inspired by jharokhas, traditional overhanging windows. Flanking these are arched windows with white borders, all topped by a sloping roof made of red terracotta tiles.

Across the palace, the doors vary in size and treatment. The main gate is made of iron grills framed within a brick arch. Inside, doors are mostly wooden, some plain, some detailed with carved beams or iron inserts. Most of them feature latch-and-bolt mechanisms which are still in use today.

The windows also differ. Some are traditional wooden shutters, others have colored glass or are painted in soft pastel tones. A few are shaded by small overhangs called chajjas (roof-like projections to protect from sun and rain), adding a little character to the façades.

The roofing system is made from overlapping clay tiles laid over timber rafters. This setup is common in the Konkan region and helps drain heavy monsoon rains effectively. The rooflines include gable ends and extended eaves that shade the walls below.

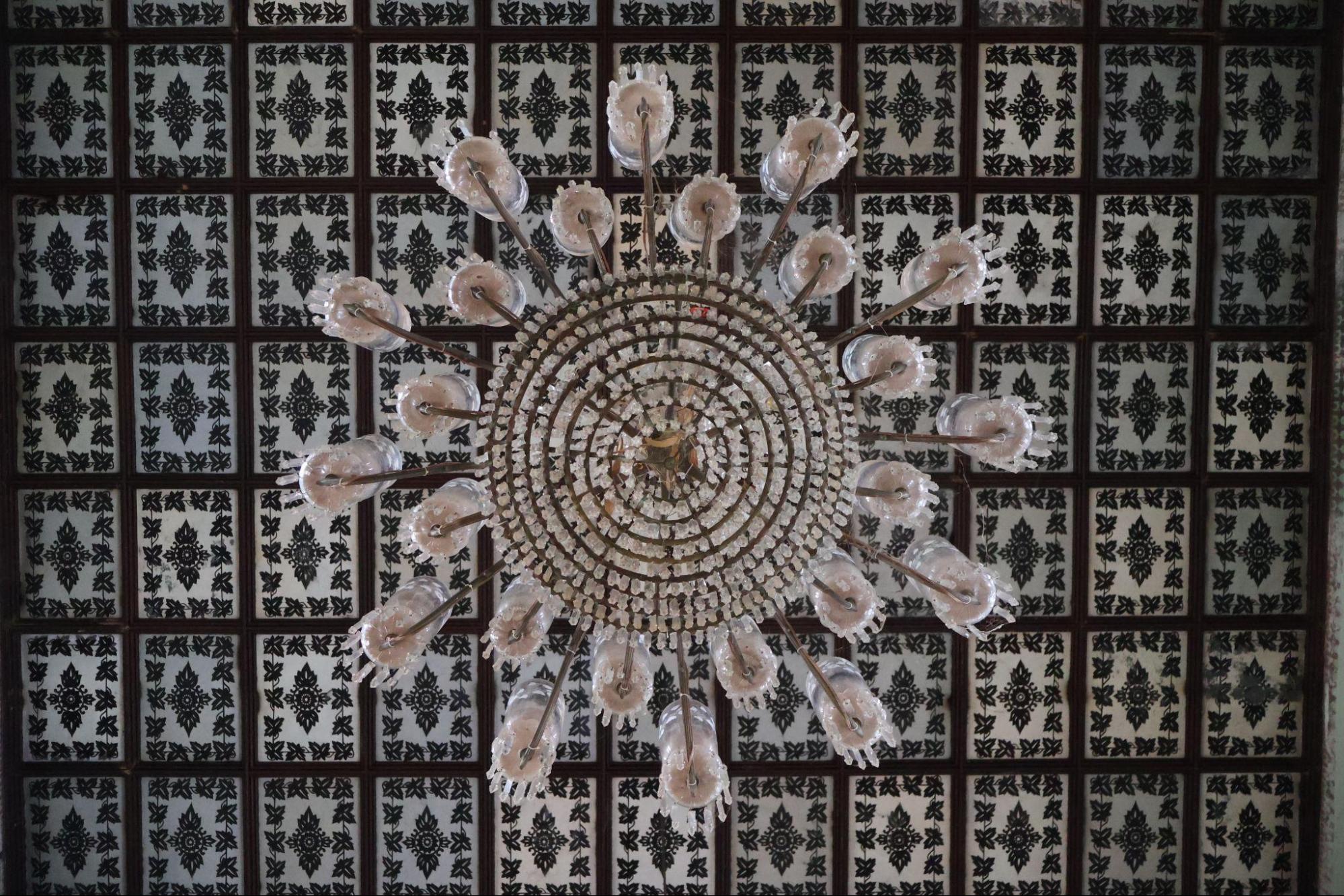

Inside, the Darbar Hall remains one of the most striking spaces in the palace. The foundation stone was laid by the then Governor of the Bombay Presidency, Sir James Fergusson, on 21 March 1881, and the hall was completed during the reign of Raghunath Sawant Bhonsle (1867–1899). It served as the hall of audience, where the ruler conducted court and met with dignitaries and officials. The ceiling is lined with etched zinc plates forming floral and geometric motifs, and two grand chandeliers, dating back to the 1880s, still hang in place.

A stone staircase connects the two levels of the palace. Its iron railings and wooden handrails reflect the craftsmanship seen throughout the building.

Today, the palace remains under the care of the Sawant Bhonsle family. Some portions have been adaptively reused, including the transformation of one wing (Taisaheb Wada) into a heritage boutique hotel. The site also supports the revival of local craft traditions such as Ganjifa card painting and lacquerware, both historically patronised by the royal court.

Sawantwadi Palace continues to be a prominent structure within the town, not only for its architecture, but for the way it holds together the city’s older patterns of residence, ceremonial life, and craft tradition.

A Mud House from the mid-20th Century at Ringewadi

Ringewadi is a small village in Vaibhavwadi Taluka of Sindhudurg. Tucked along an internal road is a 70-year-old mud house that quietly reflects the region’s traditional building practices. Built using mud, stone, and timber, the house follows a linear layout with a sloped tile roof, typical of rural homes in this part of the Konkan.

The structure rests on a raised stone plinth that extends slightly beyond the walls. This edge serves as a threshold but also as a place for passersby to pause, sit, or gather, a functional feature that also carries a social role within the village setting.

The house is built using locally available materials. The walls are made of thick mud layers, offering insulation and regulating indoor temperature. The foundation and compound wall are built in stone, anchoring the structure firmly to the ground.

Timber is used throughout the framework, especially in the roof structure, door and window frames, and support beams.

The sloped roof is covered with overlapping clay tiles, supported by wooden rafters. The extended eaves form a narrow verandah, offering shade and protecting the mud walls from rain and a practical response to the Konkan region’s heavy monsoons.

A small courtyard opens in front of the house. At its edge stands a Tulsi plant, placed in a raised platform, a feature common across many olden homes in Maharashtra.

The courtyard often doubles as a parasbaug, where herbs, vegetables, and medicinal plants are grown and used in everyday cooking. This green buffer also supports daily routines like drying grains, sitting outdoors, or hosting informal gatherings.

The house has a basic wooden door with a plain frame and recessed panels. The locking system on the doors is minimal but distinct, often using a traditional bar mechanism.

The windows are small, with wooden frames and louvers to allow ventilation while maintaining interior shade. Openings above the doors are included for airflow.

Sources

Amitabh Gupta. 2022. Vijaydurg Fort is a sentinel with stories of Maratha warfare and resilience. The Telegraph.https://www.telegraphindia.com/my-kolkata/pl…

Ashwini Ashok. 2022. Shri Lakshminarayan Temple, Walaval, Sindhudurg. The Brown Wildflower.https://www.thebrownwildflower.com/shri-laxm…

Government of India. Shree Dev Kunkeshwar Mandir. Utsav.https://utsav.gov.in/view-darshan/shree-dev-…

Government of Maharashtra. Sindhudurg. Maharashtra Tourism.https://maharashtratourism.gov.in/fort/sindh…

Government of Maharashtra. Vijaydurg. Maharashtra Tourism.https://maharashtratourism.gov.in/fort/vijay…

India.com. Forts: Sindhudurg Fort. India.com.https://www.india.com/travel/tarkarli/things…

India.com. Forts: Vijaydurg Fort. India.com.https://www.india.com/travel/tarkarli/things…

Mayekar’s Holiday Home. Kunkeshwar Temple. Mayekar’s Holiday Home.https://mayekarsholidayhome.in/kunkeshwar-te…

Sawantwadi Palace. Steeped in History - Sawantwadi Palace.https://www.sawantwadipalace.com/aboutus

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.