Contents

- Etymology

- Ancient Period

- Tabashir and Trade of Medicinal Substances

- Satavahanas and the Trade Routes of the Early Common Era

- Western Kshatrapas and the Changing Control over Konkan

- The Mauryas of Konkan and their Inscription near Thane

- Spread of Buddhism and the Lonad Caves

- Shri-Sthanaka and the Shilaharas of North Konkan

- Shri Kopineshwar Mandir

- Ambarnath Mandir

- Yadavas and their Land Grants

- Mentions in the Writings of Arab Geographers

- Medieval Period

- Jordanus Catalani & theSpread of Christianity

- Local Chiefs of Thane

- The Rise and Fall of the Gujarat Sultanate

- The Arrival of the Portuguese

- Thane Under Portuguese Rule

- Spread of Christianity

- Conversion Strategy and the Rise of the Church

- The Landholding Systems of the Portuguese

- Shipbuilding and Maritime Industry

- Ghodbundar Fort or 'Cacabe de Tanna’

- Conflict at Mahuli Fort

- The Contest forKalyan and the Durgadi Fort

- The Siege of Ghodbunder and the Fall of the Portuguese

- Thane under the Marathas from the French account

- Rise of the East India Company

- Colonial Period

- Administrative Reorganizations

- Famines in the Early 19th Century

- Uprisings by the Kolis and Bhils

- Defiance for Holi

- The First War for Independence, 1857

- Income Tax Resistance

- Local Robberies

- Thane Terminus and the First Railway in India

- Decline of Thane’s Maritime Economy Under British Rule

- India’s Struggle for Independence

- Ambernath Ordnance Factory

- Post-Independence

- Siemens Kalwa factory

- Partition Refugees in Ulhasnagar

- Sources

THANE

History

Last updated on 18 August 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

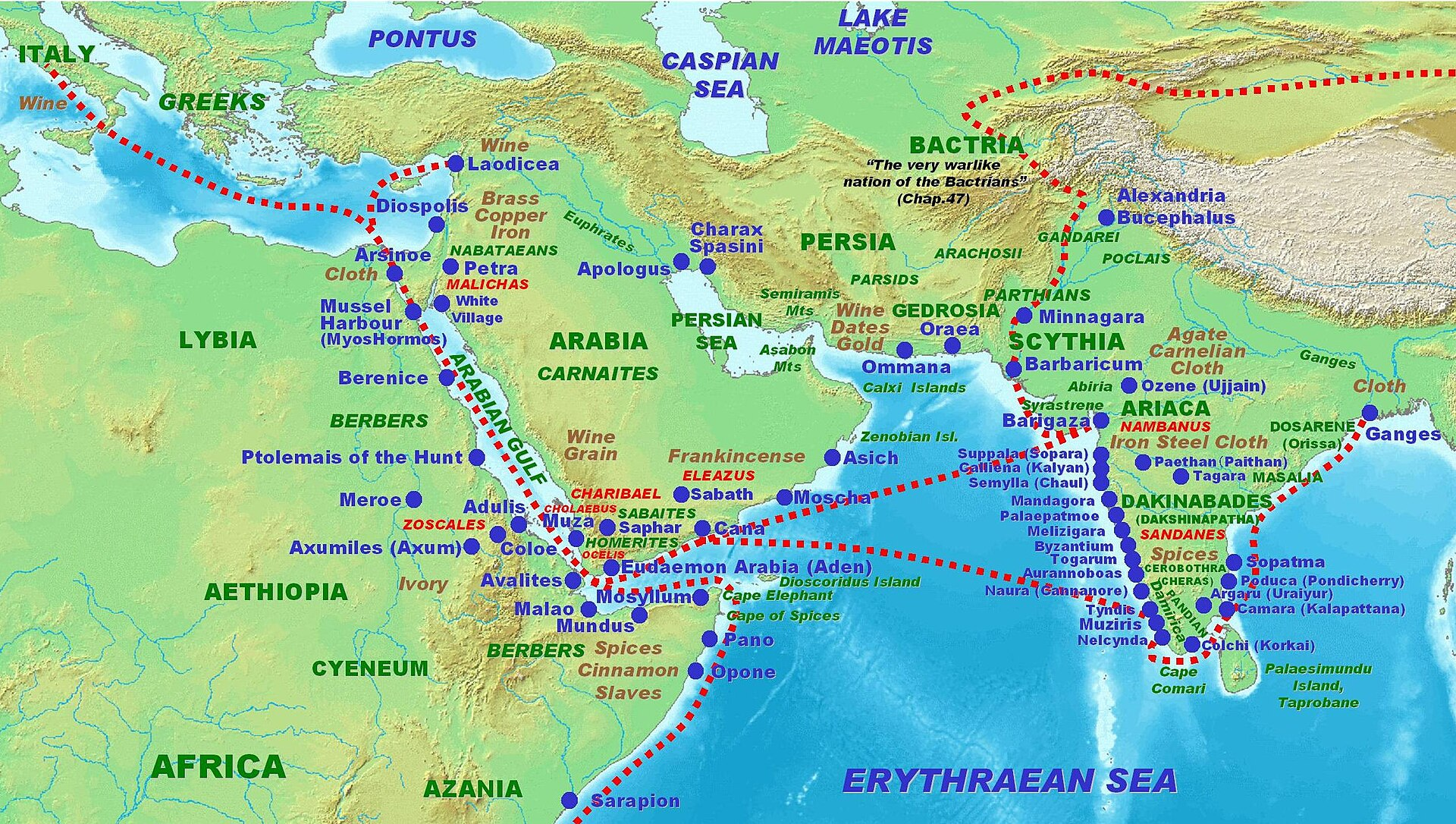

Thane district, located along the Konkan coast of western India, is a region of long-standing historical and commercial importance. Its coastal location enabled early trade links, both maritime and inland, connecting the region to the Deccan plateau. In the past, Thane was home to many ports, many of which were connected to the Roman and Arab worlds. Notably, Kalyan, which is one of its principal settlements today, is even mentioned in the Greco-Roman text Periplus, which offers a glimpse into its role as a key trading centre in the early historic period. Over the years, the area grew into a cosmopolitan trading zone, as seen by its cultural and linguistic diversity.

Thane later came under the rule of several dynasties, including the Satavahanas and the Shilaharas, the latter of whom are believed to have established their capital in the district. Later, Portuguese and the British held much influence. In 1695, the Italian traveller Gemelli Careri, passing through Portuguese-held Daman, Vasai, and Salsette, identified Thane as one of the chief towns of the region, noting its open setting, three monasteries, and the manufacture of calicoes. The district also witnessed local resistance to colonial rule and went on to play a notable role in India’s freedom movement.

Etymology

The present name Thane is a modified form of the older term Thana, which remained in common use until 1996. Significant historical evidence of Thane’s ancient identity comes from the discovery of a copper plate inscription dating back to 1078 CE, which was unearthed near the foundations of Thane Fort in 1787. This plate records a land grant issued by Arikesara Devaraja, the raja of Tagara/Ter (in present day Dharashiv district), in which he addresses the residents of a city called "Sri Sthanaka.” This has led some scholars to speculate that it refers to the area that included Thane.

Over the centuries, the name has undergone several transformations. In Romanized sources, it has appeared in various forms, including Tana, Thaṇa, and Thame. Notably, historical travelers and chroniclers such as Ibn Battuta and Abulfeda referred to it as Kukin Tana, while Portuguese Duarte Barbosa used the term Tana Mayambu. These variations, in many ways, reflect the district’s evolving identity and its long-standing prominence in regional and maritime history.

Ancient Period

The district of Thane has historically played a crucial role in facilitating movement between the Deccan plateau and the western sea. Its location enabled access to key maritime routes, and its coastline supported a number of thriving ports that linked the region to trade networks stretching across the Indian Ocean and beyond. These early exchanges are documented in the colonial district Gazetteer (1882), which records:

“From pre-historic times the Thana coast has had relations with lands beyond the Indian Ocean. From B.C. 2500 to B.C. 500 there are signs of trade with Egypt, Phoenicia, and Babylon; from B.C. 250 to A.D. 250 there are dealings with, perhaps settlements of, Greeks and Parthians; from A.D. 250 to A.D. 640 there are Persian alliances and Persian settlements; from A.D. 700 to A.D. 1200 there are Musalman trade relations and Musalman settlements from Arabia and Persia.”

Many parts of the present-day Thane district also lay along inland routes which connected coastal ports with the Deccan. Among these ports, Sopara (which lies in present-day Palghar district) was a prominent early centre of maritime trade. Situated nearby, it likely played a central role in this network, with goods moving inland through Thane’s creeks, wooded tracks, and hill passes.

Tabashir and Trade of Medicinal Substances

Among the more distinctive exports from the region was tabashir, a translucent, crystalline substance extracted from the nodal joints of certain species of bamboo. Known in Sanskrit as tvakṣīra (त्वक्षीर), literally “bark milk,” tabashir was widely used in both Ayurvedic and Unani medical systems. It was also referred to by names such as vaṃśa-śarkarā (bamboo sugar), vaṃśa-karpūra (bamboo camphor), and bamboo manna.

According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1882), tabashir was prepared in parts of the Konkan and was already known in global trade by the 1st century CE. It appears in the writings of Pedanius Dioscorides, a Greek physician and pharmacologist who practiced in Rome during the reign of Emperor Nero. This reference, one of the earliest by a Western author, in many ways underscores the wide reach of Thane’s medicinal trade via Arab and Persian intermediaries.

Tabashir was believed to possess a range of therapeutic properties. Early medical compilations describe it as an antipyretic (fever-reducer), antispasmodic (relief for muscle spasms), and antiparalytic agent, with restorative and even aphrodisiac qualities. Its continued relevance in contemporary Ayurvedic and Unani practice suggests a longstanding recognition of its medicinal value. Some accounts propose that its earliest use may have originated among the indigenous communities of central and western India, from whom knowledge of its preparation and use may have passed into formal medicinal systems.

The economic potential of tabashir was also noted by British administrators and scientists. Edgar Thurston and George Watt, in their Dictionary of the Economic Products of India (1885), recorded its trade and properties in detail.

Satavahanas and the Trade Routes of the Early Common Era

The territory that now forms Thane district has, at various times, fallen under the authority of different kingdoms. Little is known about its early history, however, available archaeological findings and a few literary references allow for a general outline, particularly when situated within the wider histories of the Konkan and Deccan regions

One of the earliest epigraphic records in the Konkan region comes from Sopara, known today as Nala Sopara in Palghar district. Here, stone inscriptions carved during the reign of Ashoka, who reigned in the 3rd century BCE, have been found engraved on basalt rock. These edicts, written in the Brahmi script, were part of Ashoka’s effort to spread Buddhist values across his realm. Sopara was likely a significant religious and trade centre at the time. Since Thane lies nearby, it is possible that it, too, was connected to the administrative or cultural reach of the Mauryan state.

With the decline of Mauryan power, control of the region appears to have passed to the Satavahanas, whose authority extended over large portions of the Deccan from a capital at Paithan (in present-day Sambhaji Nagar district). Under their administration, overland and coastal trade routes flourished; and fascinatingly this period of their powerful reign saw increased movement of textiles, metalware, ivory, and timber from the interior toward the ports of the western coast, where they entered long-distance exchange systems.

One of the ports active in this network was Kalyan, located along the Ulhas River in what is now Thane district. With its tidal creeks and river access to the sea, Kalyan served as both a port and a redistribution centre, linking overland trade from the Deccan plateau to maritime routes across the Arabian Sea. Notably, some scholars identify Kalyan with Calliena, a port described in the Periplus Maris Erythraei, a 1st-century CE Greco-Roman guide to Indian Ocean trade. The Periplus refers to Calliena as a harbour frequented by ships from Arabia and the Roman world, drawn by the goods of western India. This identification, in many ways, hints at how Kalyan was part of a wider trade network that linked the western Deccan to ports across the Indian Ocean and beyond in its early history.

Exports from the region during the Satavahana period are known to have included cotton textiles (chintzes and muslins), metal goods such as iron and copperware, and luxury materials including ivory and ebony. In return, merchants brought in goods such as silks, cloves, sandalwood, and aloes from Southeast Asia, along with items from the Mediterranean region.

This commercial activity is reflected in the growth of religious institutions during the same period, particularly those associated with Buddhism, which had strong ties to merchant communities. The Kanheri Caves, located in present-day Borivali (Mumbai Suburban district), approximately 10 km south of the present-day Thane city, were excavated and expanded between the 1st century BCE and 3rd century CE. As in other parts of western India, Buddhist monasteries in this region were often situated along trade routes and supported by donations from traders, guilds, and wealthy patrons.

Interestingly, inscriptions at Kanheri record contributions from merchants and guilds based in Kalyan and other settlements within the present-day Thane district. It is noted in the district Gazetteer (1882) that, “Kalyan is mentioned in nine inscriptions (in caves 2, 3, 12, 36, 37, 56, 59, 89, and on a detached stone between 14 and 15).” These inscriptions, taken together, indicate that monastic establishments such as Kanheri were closely associated with the trade routes of the period, and that settlements within the present-day Thane district, particularly Kalyan, formed part of a wider network of commercial and religious activity during the Satavahana period and in the years that followed.

Western Kshatrapas and the Changing Control over Konkan

By the late 1st century CE, the inland and coastal routes passing through present-day Thane district came under pressure from new political forces. Among the most prominent of these were the Western Kshatrapas, a dynasty of rulers with origins in Parthia (in present-day northern Iran), who entered western India through Rajasthan and Gujarat.

One of their early and most powerful leaders was Nahapana, who controlled a large part of western India, including Konkan, North Maharashtra, and parts of the Deccan plateau. His inscriptions and coinage have been found across the region, including at Nasik, Junnar, and Karle, suggesting strong political and military presence across trade corridors.

Though no inscriptions of Nahapana have yet been discovered in Thane district, his control likely extended here during the peak of his influence in the early 2nd century CE. This is supported by evidence of upheaval in the region noted in the colonial district Gazetteer (1882), which notes that, “During this period, the Satakarnis [Satavahanas] were displaced by outsiders, seemingly Scythians or Parthinaians from North India.”

The Western Kshatrapas, known in Sanskrit as Pahlavas, gradually assimilated into local society, adopting Marathi names, entering into local marriages, and supporting Buddhist and Brahmanical institutions.

The control of the Western Kshatrapas was eventually challenged by the Satavahanas. Gautamiputra Satakarni, one of the most renowned rulers of the Satavahana line, is credited with defeating Nahapana and regaining large parts of western India, including Konkan. His victory is recorded in inscriptions at Nasik Caves (in present-day Nashik district), where his mother Gautami Balashri details his military conquests.

However, this restoration of Satavahana power was not permanent. According to the Thana Gazetteer (1880), “about the close of the second century, Rudradaman, one of the greatest of the Kshatrap kings of Gujarat, has recorded a double defeat of a Shatakarni and the recovery of the north Konkan.”

Rudradaman I, the grandson of Chastana (Nahapana’s successor), pushed back into Konkan and reasserted Kshatrapa control around the end of the 2nd century CE. His victories were recorded in the famous Junagadh rock inscription in Saurashtra (in present-day Gujarat), and his reach likely included key towns and ports along the Thane coastline.

The Mauryas of Konkan and their Inscription near Thane

By the early 4th century CE, as the influence of the Western Kshatrapas began to recede from western India, the Konkan region saw the emergence of smaller, lesser-known dynasties that governed over localized territories. One such lineage appears to have been a Maurya family, distinct from the earlier Maurya Empire, but likely descended from or inspired by them in name and political tradition.

An important record from this period comes in the form of a stone inscription discovered north of Thane, dated to the 4th or 5th century CE, which mentions a Maurya king named Suketuarma ruling in the Konkan. It is mentioned in the colonial district Gazetteer (1880) that “A stone inscription from north of Thane from the 4th or 5th century mentioned a Maurya king named Suketuarma ruling in Konkan.”

The inscription’s presence in the nearby region, likely suggests that Suketuarma’s domain likely included areas within or near modern Thane district.

Spread of Buddhism and the Lonad Caves

By the 5th century CE, the area corresponding to present-day Thane district had become integrated into important inland trade and pilgrimage corridors. Along these routes, Buddhist monastic activity began to take visible form, often marked by rock-cut cave sites. One such site of interest is the Lonad Caves, situated near Janwal village, just north of Kalyan, an area that would, over the centuries, grow into a key regional node.

The Lonad Caves are notably significant in the context of Thane’s early religious landscape. They likely served as resting places for travelling monks or merchants. A contemporary source, Documentation of Caves in MMR, notes: “The Lonad cave was present on the trade route from Sopara to Kalyan and in the later period from Ghodbunder to Kalyan.”

This positioning implies that the site likely formed part of a broader Buddhist trade and monastic network traversing the North Konkan region.

In the mid-6th century CE, the Chalukyas of Badami expanded into the Konkan region. Kirtivarma I, one of the early Chalukya rulers, is believed to have led military expeditions toward the western coast. It is likely that the Chalukyas extended their influence into parts of present-day Thane district.

This presence, however, was not long-lasting. By the early 7th century CE, Chalukya authority began to weaken, creating space for local chiefs to assert control. Among these was Jadav Rana, a regional ruler associated with Sanjan, in the area now falling within Valsad district, Gujarat. Sanjan, though outside present-day Thane’s administrative boundaries, maintained close cultural and economic ties with the northern Konkan.

These regional links are supported by epigraphic findings in the Palghar district (refer to Palghar for more), indicating that Jadav Rana’s influence extended southward. Interestingly, a moment of note of his reign is mentioned in the colonial district Gazetteer (1883), where it is written that when Persian refugees (likely Zoroastrians) fled to Konkan after the fall of the Sassanian Empire (625–638 CE), Jadav Rana gave them refuge. This act marks one of the earliest documented instances of refugee settlement in the region. It is also possible that Jadav Rana was an early Yadava ruler, possibly belonging to a local branch that predated the Seuna Yadavas of Devagiri.

Shri-Sthanaka and the Shilaharas of North Konkan

From the early 9th century CE, the northern Konkan region came under the rule of the Shilahara dynasty. Their jurisdiction extended from the present-day district of Raigad, Thane and southward to Ratnagiri. Among the various towns under their dominion, Shri-Sthanaka, now identified with modern Thane, acquired particular importance.

The town served as the chief administrative seat of the northern branch of the Shilahara family, and its name occurs frequently in copperplate grants and inscriptional records of the period. Fascinatingly, one such grant, dated 1018 CE, and cited in the colonial district Gazetteer (1882), it is mentioned that, “Shri-Sthanaka was one of the chief towns of a family of Shilahara chiefs, who ruled over 1400 Konkan villages.”

Its prominence as an urban centre during this period is further supported by archaeological remains and epigraphic discoveries within the vicinity, which collectively point to the establishment of a well-organised local administration and sustained royal patronage. In Charai, a neighbourhood in Thane, fragments indicative of Shilahara occupation have been recovered. In addition, sculptural remains dating to this era include an image of Bhagwaan Brahma found near Siddheshwar Lake, and a figure of Vishnu discovered at Jondhalibagh.

Shri Kopineshwar Mandir

There are also a few religious sites in the district that are associated with the period of Shilahara rule. Among the prominent is the Shri Kopineshwar Mandir, located along the eastern bank of Masunda Lake in Thane city. It is among the oldest religious sites in the district and is dedicated to Bhagwaan Shiv, who is considered to be the gram-devta (village deity) of Thane.

The current mandir structure was constructed around 1760 CE by Ramaji Mahadev Bhivalkar, a Sarsubhedar under the Maratha administration, following the Maratha takeover of Salsette. Today, the Shri Kopineshwar Mandir remains an active place of worship. Despite being situated in a densely developed area, it continues to draw daily devotees and holds an enduring place in the city’s religious and historical landscape.

Ambarnath Mandir

Another important architectural marker of Shilahara patronage is the Ambarnath Mandir, in the eastern suburban city of Ambernath. Built in 1060 CE, the Mandir is believed to have been commissioned by Chhittaraja, a ruler from the North Konkan branch of the Shilahara dynasty. The structure is dedicated to Bhagwaan Shiv and is among the finest examples of medieval temple architecture in the region.

Interestingly, a local legend, however, places the origin of the mandir even earlier. It is said that during their exile, the Pandavas sought refuge at the site where the mandir now stands. To protect themselves from Duryodhan’s spies, they are believed to have built a mandir in honour of Bhagwan Shiv. According to the story, the Pandavas constructed the entire structure in a single night, but left the shikhara unfinished in their haste.

Yadavas and their Land Grants

By the early 13th century CE, parts of the present-day Thane district had come under the administration of the Yadava dynasty of Devagiri. Epigraphic evidence attests to the exercise of authority in the Konkan region during the reign of Ramachandradeva (r. 1271–1309 CE), under whose rule several land grants were issued.

Two notable copperplate grants, dated 1273 CE and 1291 CE, refer respectively to the donation of the villages of Anjor (in the vicinity of modern Kalyan) which was conferred by local officers operating under Yadava authority. Additional inscriptions recovered from Bhiwandi (1280 CE) and Vasai from the nearby Palghar district (1288 CE) record endowments executed during the same reign, thereby indicating the inclusion of this territory within the Yadava administrative system.

Mentions in the Writings of Arab Geographers

By the 13th century CE, under Yadava rule, Thane had come to be recognised as an active port in regional and overseas trade. Arab geographers such as Al-Biruni and Al-Idrisi, and later Marco Polo, refer to it as a place with “many ships,” engaged in commerce with Persia, Arabia, and the Malabar coast.

Goods exported from the region included rice, salt, betel nuts, coconuts, and cotton textiles. In return, traders brought in dates, wine, pearls, and large numbers of horses, sometimes as many as 10,000 at a time, meant for military use in the interior.

Interestingly, merchants from diverse communities were involved in this trade. The Gujarati Vanias are mentioned as principal traders in Thane’s ports, though local Muslim, Hindu, and Parsi merchants were also active. Foreign traders from Arabia, Persia, Europe, and possibly even China are believed to have frequented the region.

Writers from the 9th and 10th centuries also note that the language of trade in Thane was Lar, which served as a common tongue across the western coast and remained in use into the early modern period. See roots of cultural and linguistic diversity since then. These observations, in many ways, point to a longstanding tradition of cultural and linguistic plurality in the district.

Medieval Period

In the early 14th century CE, the northern Konkan, including present-day Thane district, began to come under the growing influence of the Delhi Sultanate. This expansion was led by Alp Khan, a prominent general in the service of Alauddin Khilji. After consolidating power in Gujarat, Alp Khan turned his attention further south. The coastal town of Sanjan, now in Gujarat but closely connected to many Konkan regions, was captured between 1312 and 1318 CE, following resistance from local chiefs and the local Parsi community.

It is important to note that until this time, many parts of the region had remained under the control of the Yadava dynasty of Devagiri. Ramachandra, one of the last major Yadava rulers, held sway over parts of Gujarat, including Navsari. Following his death in 1309 CE, his son Shankar succeeded him, but his refusal to pay tribute to Delhi invited military retaliation. In 1312 CE, Shankar was killed in battle, and authority passed briefly to his son-in-law Harpaldev. However, by 1320 CE, even Navsari had fallen, and the Sultanate began to appoint its own officials in the region, among them Malik-ul-Tujjar, or “Chief of Merchants,” a title that underscores the growing importance of trade in Sultanate administration.

These events, inevitably, marked a turning point in regional governance and the fall of Devagiri in 1318 CE allowed the Delhi Sultanate to extend its frontier further into the Konkan, where they are noted to have secured key coastal outposts such as Mahim (in present-day Mumbai City) and Thane. The colonial district Gazetteer (1882) offers some insight into this period of transition, noting that,

"The strong Musalman element in the coast towns probably made this an easy conquest, as no reference to it has been traced in the chief Musalman histories. [Malik Kafur, in his expedition to the Malabar coast in 1310, found Musalmans who had been subjects of Hindus. They were half Hindus and not strict in their religion, but, as they could repeat the kalima, they were spared. Amir Khuaru in Elliot and Dowson, III, 90.]"

Jordanus Catalani & theSpread of Christianity

In the years immediately following the Delhi Sultanate's consolidation of power in the Konkan, Thane not only came under new political administration but also became the site of one of the earliest recorded instances of European missionary activity on India’s west coast. While the spread of Christianity in Thane is commonly associated with the arrival of the Portuguese, who would later establish a significant presence in the region (discussed below), missionary contact predates them by nearly two centuries.

As early as 1323 CE, Thane was visited by French friars and religious travellers. Among the earliest was Jordanus Catalani, a Dominican friar from southern France, who arrived between 1321 and 1324 CE, during the early years of Sultanate rule. He is believed to have undertaken evangelistic work in Thane, Chaul (in present-day Raigad district), and other parts of the western coast, making him one of the first known European missionaries to operate in India.

Interestingly, both he and Oderic recorded their observations in travel accounts that provide rare insight into the region during the early Sultanate period. They describe the new political order under the Delhi emperor, noting that Thane was governed by a military officer (malik) and a religious official (qazi). The colonial district Gazetteer (1882) summarizes their account as follows:

“The friars state that the Saracens, or Muhammadans, held the whole country, having lately usurped the dominion. They had destroyed an infinite number of idol temples and likewise many churches, of which they made mosques for Muhammad, taking their endowments and property.” (Jordanus Mirabilis, p. 23)

The friars also recount the execution of four Christian missionaries by order of the local qazi. The act is said to have provoked the Delhi court, and the offending governor was recalled and put to death.

Aside from political and religious affairs, the friars also took note of the local environment. Thane, they wrote, was so hot that standing bareheaded in the sun could prove fatal. Despite this, the region was heavily forested and rich in natural resources. Trees such as jackfruit, mango, teak, and fan palms were commonly found, along with deposits of iron, gold, and electrum.

They also described the region’s fauna, including leopards, crocodiles, and what they referred to as “black lions”—possibly a reference to melanistic leopards. Oxen, widely used for transport and agriculture, were described not only as work animals but also as sacred, even referred to by some as “fathers” and worshipped in local custom.

Local Chiefs of Thane

Following the decline of the Khilji dynasty, the Tughluqs rose to power in Delhi during the early 14th century CE. However, their engagement with the Konkan appears to have been limited. According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1883), the region around Thane held little strategic or commercial value for the Tughluq administration, particularly as major trade routes began to shift northwards through Gujarat.

The traveller Ibn Battuta, who passed through western India in 1343 CE, makes no significant mention of Thane as a port of consequence. Instead, he records that commercial traffic was largely flowing through Cambay (Khambhat, Gujarat) and Songadh (Tapi district, Gujarat), bypassing the coastal routes that once linked Daulatabad (near Aurangabad, Maharashtra) with the Thane ports. A note in the Gazetteer summarises the situation:

“Under the strong rule of Muhammad Tughluq (1325–1350), the Musalmans probably maintained their supremacy in the north Konkan… but their interest in this part of their dominions was small. The route taken by the traveller Ibn Batuta (1343) shows that, at this time, the trade between Daulatabad and the coast did not pass to the Thana ports, but went round by Nandurbar and Songad to Cambay. (Lee’s Ibn Batuta, pp. 162–164; Yule’s Cathay, Vol. II, p. 415)”

At the same time, it seems that the Sultanate’s limited presence in the region allowed local chiefs to retain significant authority. Along the inland trade routes between the Deccan and the coast, two rulers in particular held considerable sway: the Mandev chief of Baglan (in present-day Nashik district) and the chief of Jawhar (Jwahar being a region that lies in present-day Palghar district). In 1341 CE, the latter was formally recognised by the Delhi court as ruler over twenty-two forts and a territory said to yield an annual revenue of ₹9,00,000.

In practice, Thane and its surrounding areas remained under the control of regional power-holders, rather than imperial officials. The Gazetteer (1882) notes that, figures such as the Hindu chief of Bhiwandi (in present-day Thane district) continued to issue land grants during this period, a strong indication of continued local authority in both administrative and landholding affairs, despite nominal inclusion within Sultanate domains.

As the authority of the Delhi Sultanate receded from the Deccan following the decline of Tughlaq authority, new regional powers began to emerge in both the Deccan and Gujarat. Among the first of these was the Bahmani Sultanate, which established its independence from Delhi in the mid-14th century. While the Bahmanis successfully extended their influence across the Deccan plateau, their engagement with the Konkan, and particularly with Thane, appears to have been limited in their early years.

However, some shift occurred between 1485 and 1493 CE, when Ahmad Nizam Shah, son of the Bahmani prime minister who would later become the founder of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, was appointed governor of Daulatabad. He made Junnar (in present-day Pune district) his headquarters and led campaigns to secure several forts across the Pune and Thane regions, including Mahuli (Shahapur taluka, Thane district) and Manranjan or Rajmachi (near Lonavala, Pune district).

It is important to note, that during this whole period, it is noted that the ports of Thane had seen a decline in commercial prominence.

The Rise and Fall of the Gujarat Sultanate

Meanwhile, further northwest, the political landscape of Gujarat was also undergoing transformation. In 1394 CE, Muzaffar Shah I, previously a governor under the Tughlaqs, declared independence and founded the Gujarat Sultanate. Over the course of the 15th century, the Gujarat rulers, particularly Ahmad Shah I and Mahmud Begada (r. 1458–1511 CE), expanded their domain southward along the coast, bringing much of northern Konkan, including Thane, into their sphere of influence. According to the colonial District Gazetteer (1883), this was a period that saw a resurgence of political and commercial interest in the region. Ports such as Bassein (Vasai), Bombay (now Mumbai City), and Thane began to receive more attention under this new regime.

Under Mahmud Begada, efforts were made to consolidate and administer the region more systematically. The District Gazetteer (1883) records that the Sultanate divided North Konkan into five administrative divisions, with Thane serving as one of the key zones. Garrison towns were established at Bassein (Vasai, Palghar district), Bombay (Mumbai City), and Nagaon (in present-day Raigad district) to maintain order and secure coastal trade routes.

The Arrival of the Portuguese

By the early 16th century, Portuguese ships had begun to appear regularly along the Konkan coast, marking the start of European engagement in western India. Their initial encounters with local powers were largely commercial. They sought to break the monopoly held by Arab and Egyptian merchants over trade between Europe and Asia and viewed Indian rulers, particularly those of Gujarat, as potential allies or, if necessary, adversaries.

According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1882), efforts were made to establish friendly relations. Captured Gujarati ships were reportedly returned with cordial messages, reflecting an early diplomatic tone. However, as the Portuguese ambitions expanded, especially after securing Goa in 1510, their policy shifted toward military assertion.

Tensions with the Gujarat Sultanate intensified during this period, as both powers vied for control over coastal trade. According to the district Gazetteer (1883), one of the strategies adopted by the Portuguese involved inciting local opposition to the Sultanate. In 1507 CE, they attempted to stir discontent among Hindu chiefs along the Thane coast, encouraging them to resist the authority of Sultan Mahmud Begada. That same year, they seized Chaul (in present-day Raigad district), establishing what would become one of their first strategic footholds on the mainland.

Over the following decades, sporadic conflict and diplomacy alternated. Portuguese forces sought to establish fortified settlements along the coastline. In one campaign, they demanded permission to build a fort at Diu, but were denied. In response, they launched a series of coastal raids, burning towns between Vasai (Palghar district) and Tarapur (Palghar district), capturing tribute from Thane and Bandra (Mumbai Suburban district), and attempting to seize the fort at Daman.

By the 1530s, Portuguese efforts intensified under Nuno da Cunha, then governor of Portuguese India. In 1530 CE, he led coordinated assaults on Thane, Bassein (Vasai), and Chaul, aiming to decisively break Gujarat’s hold over the northern Konkan. These operations were part of a broader strategy to secure Portuguese dominance over the Arabian Sea trade routes.

The campaign culminated in the Treaty of Bassein (1534 CE), in which Bahadur Shah of Gujarat ceded Thane, Bassein, and Salsette to the Portuguese. These territories were incorporated into the Portuguese Estado da Índia, and fortified settlements soon followed.

Thane Under Portuguese Rule

Geographically, parts of present-day Thane district fell within the bounds of Salsette Island, particularly its eastern stretches. Under Portuguese rule, Thane and these adjacent areas were treated as a single territorial unit, marking a shift in both governance and spatial organisation.

One of the earliest and most vivid descriptions of the region during Portuguese rule comes from Dom João de Castro, a Portuguese nobleman, naval commander, and later the 13th governor and 4th viceroy of Portuguese India. Passing through in the mid-16th century, he recorded his impressions in Primeiro Roteiro, a travelogue of considerable historical value. Thane, he wrote, was a place of both historical significance and material prosperity, home to 900 gold-lace looms and 1,200 white-cloth looms. Salsette, he noted, was famous for the ruins of the “great and beautiful city of Thana,” as well as for the massive cave temple of Kanheri (Borivali, Mumbai Suburban district). The surrounding hills were heavily forested, offering ample timber for ships and galleys. Bombay (now Mumbai), which he described as a low, wooded island, had abundant game, fertile crops, and reliable harvests.

Castro also admired the architecture of Thane, describing Mandirs built without mortar, their stones precisely joined. While he referred to some as mesquitas (mosques), later scholars like José Gerson da Cunha argued that many were likely mandirs, repurposed or misidentified over time. Notably, Castro remarks that prior to Portuguese conquest, Muslim rulers no longer interfered in Hindu religious life — a detail that suggests a degree of stability before the new wave of colonial intervention.

Following the consolidation of power, the Portuguese divided Salsette into two main administrative zones: one centred on Thane, and the other covering western coastal villages (now part of Mumbai). This reorganisation laid the groundwork for further transformations in landholding, missionary activity, and political control in the decades that followed.

Spread of Christianity

Although Portuguese control in Thane began in the 1530s, Christian missionary activity in the region predated their arrival. As noted earlier, Jordanus Catalani, a Dominican friar from southern France, had travelled through Thane around 1323 CE, establishing some of the earliest Christian presence along the western coast of India.

The Portuguese, however, brought with them a more sustained and institutionalised approach to evangelisation. From the outset, their expansion along the Konkan coast was closely tied to religious conversion. According to the colonial district Gazetteer (1882), converting local populations to Christianity was a core objective, one pursued with both enthusiasm and substantial resources.

By 1534, Goa had become the seat of a bishop, and soon after, Portuguese missionaries were active across Thane, Bassein (Vasai, Palghar district), and Salsette (an island made up of parts of present-day Thane and Mumbai suburban region). One of the earliest and most active missionaries was António do Porto, a Franciscan friar who arrived in India in the 1530s. According to the Gazetteer (1882), between 1534 and 1552, he is said to have destroyed 200 mandirs, converted more than 10,000 people, and built 12 churches, alongside founding orphanages and seminaries to train local clergy.

Initially, the Franciscans led these efforts. But in 1542, St. Francis Xavier arrived in Goa with a group of Jesuits and soon took a special interest in Thane. By 1548, he had established a Jesuit seminary there, and by 1552, missionaries were regularly dispatched to surrounding areas, including Chaul (in Raigad district).

Notably, one of the oldest surviving churches in Thane today, Our Lady of Mercy Church, is believed to date back to this early period, and may have been built under Jesuit supervision, possibly even with direction from St. Xavier himself.

Conversion Strategy and the Rise of the Church

In the initial decades of Portuguese rule, the approach to conversion was largely persuasive and targeted. It is noted in the colonial district Gazetteer (1882) that missionaries focused their efforts on influential social groups, particularly Brahmins and upper-caste Hindus, believing that conversions at the top would trickle down through society. Ceremonial baptisms were held, and new converts were welcomed with both material and social incentives.

According to the Gazetteer (1882), converts were often integrated into newly formed Christian communities, supported by Portuguese resources. Land was distributed, ploughs and communal tools were provided, and religious instruction was woven into daily life, it is written in the Gazetteer that “In a few years, there was a population of 3,000. They had 100 bullocks and ploughs, and an ample store of field tools, all held in common. The villagers had religious teaching every day, and, in the evening, joined in singing the Christian doctrines.”

By the mid-17th century, the Church had grown immensely in influence and wealth. In 1634, there were 63 friars in Bassein alone: 30 Franciscans, 15 Jesuits, 10 Dominicans, and 8 Augustinians. Thane, too, had become a religious centre. By 1673, the town housed seven churches and colleges, many supported by land grants and royal patronage.

However, this missionary zeal was not without hierarchy. Elite converts, often from high-caste or noble backgrounds, were treated with particular honour, while poorer converts were exempted from paying tithes or first fruits for a period of 15 years. This layered system mirrored existing social inequalities, even as it sought to reshape religious identity.

Over time, the Portuguese authorities hardened their stance. In 1560, the Goa Inquisition was formally established. By 1580, its jurisdiction extended to areas like Chaul, Bassein, and Daman. The tone of conversion shifted — murti-making and Hindu rituals were banned, and those accused of heresy or unorthodox practices were often sent to Goa for trial.

By the late 17th century, the Church had become not only a religious force but also an administrative one. The Gazetteer (1882) records that by 1695, church revenues had surpassed those of the state, and by 1720, ecclesiastical authority was so pronounced that the Church is said to have overshadowed the Portuguese governor himself in influence across the region.

The Landholding Systems of the Portuguese

Alongside their religious and military expansion, the Portuguese also introduced new landholding structures that reshaped the agrarian economy of the region. These systems were designed to consolidate control while rewarding loyalty; they appear to have been highly feudal and seemed to reinforce sharp social hierarchies between colonial elites and the local population.

The land system in and around Thane, as elsewhere in Portuguese territories, was centered on large land grants given to fazendeiros, Portuguese landlords, retired soldiers, or beneficiaries of the Crown. These estates were usually granted at highly reduced rates, sometimes as low as four to ten percent of the regular rental value. Though nominally limited to three generations, many of these landholdings were informally renewed, allowing landlords to retain control indefinitely.

Tenants, including local cultivators and husbandmen, held no formal ownership rights. In effect, they were bound to the land, unable to leave the estate or claim any independent stake in its produce. Many large estates also maintained home farms (fazendas), worked by African slaves, adding another layer to the social and economic stratification of Portuguese rule.

Some lands were leased out under a quit-rent system, where village headmen (muqaddams) sublet parcels to farmers, who then paid a portion of their produce along with monetary taxes. These transactions were often mediated by state-appointed officials known as vendors or factors, who oversaw both rent collection and agricultural output.

By 1688, according to revenue records cited in the Gazetteer (1882), nearly half of Bassein’s (Vasai, Palghar district) income came from quit-rents alone. The remainder was generated through direct land taxes and peasant levies.

Shipbuilding and Maritime Industry

While agriculture shaped the inland economy, the coast around Thane, Bassein (Vasai), and Chaul was deeply tied to the maritime world, and during the Portuguese period, shipbuilding became one of the most significant local industries.

Indian shipbuilders had long been renowned for crafting vessels suited to the Arabian Sea’s monsoon-driven conditions. According to early Portuguese accounts, including those noted by Gaspar Correa and cited in the District Gazetteer (1882), local craftsmen employed two main techniques. In one, planks were stitched together using coir (coconut fibre) thread, a method that produced lightweight but durable boats ideal for the coast. In the other, thin iron nails with broad, riveted heads were used to fasten the planks, often reinforced from within. This created sturdier vessels capable of longer voyages.

As the Portuguese began asserting control along India’s western coastline, they absorbed many of these indigenous techniques into their own naval practices. They also looked for reliable sources of shipbuilding material. In this context, the Thane coast played a notable role. It contributed timber from the Salsette hills, which was floated down through Thane’s creeks to supply construction efforts along the Konkan coast. Smaller docks in the region supported local repairs and outfitting of coastal boats.

Alongside this local activity, the Portuguese also introduced larger, square-rigged vessels into the Indian Ocean world—such as carracks (naus) and caravels—with broad rectangular sails suited for harnessing oceanic winds. This marked a sharp departure from traditional Indian or Arab designs, which relied mostly on lateen (triangular) sails.

Interestingly, the Gazetteer (1882) notes that Vasco da Gama’s fleet, which first reached India in 1498, consisted of ships weighing between 50 to 200 tons. Within a few decades, Portuguese ships were reaching sizes of 600 to 700 tons, allowing for more cargo, greater firepower, and longer voyages.

These changes, while beneficial to some extent, also had far-reaching consequences. The dominance of these larger ships disrupted pre-existing maritime networks across the Indian Ocean which was previously led by Arab, Persian, and Indian traders. In the long run, this shift contributed to Portugal’s emergence as a dominant seafaring power in the region — but also began to alter local economies and trade dynamics in places like Thane, which was long known for being a trading hub.

Ghodbundar Fort or 'Cacabe de Tanna’

Alongside maritime infrastructure and commerce, the Portuguese also reinforced their physical control over the region through fortifications. One such stronghold, strategically placed along the Thane coast was Ghodbunder Fort, which is referred to in Portuguese sources as Cacabe de Tanna.

Built around 1550 CE, shortly after the Portuguese occupation of Thane (1530s) and Bassein (Vasai), the fort was strategically located on a hill near the Ulhas River in the present-day Ghodbunder area of Thane city. From this vantage point, the Portuguese could monitor both riverine traffic and inland movements.

Interestingly, the name Ghodbunder, derived from ghoda (horse) and bunder (port), reflects its former role as a docking point for Arabian horses brought by sea, a vital import for military and elite households in the Deccan. The Portuguese, well aware of the value of this trade, maintained a stronghold here not only for commerce but as a base of strategic control.

Conflict at Mahuli Fort

It is important to note that by the mid-17th century, while the Portuguese were consolidating their stronghold along the western coast, they were far from the only power in play. The inland Konkan region, including that of Thane was becoming a contested frontier between the Marathas, the Adil Shahi Sultanate of Bijapur, and the Mughals. Coastal towns like Bassein (Vasai) and Chaul remained under Portuguese control, but inland, influence shifted rapidly between empires.

One of the earliest strongholds to feature in this shifting power balance was Mahuli Fort, located near the present-day Shahapur taluka. Situated at over 2,800 ft., the fort overlooked the passes linking the Konkan to the Deccan, making it a valuable asset in any military campaign. The district Gazetteer (1882) notes that the fort had earlier been held by the Raja of Jawhar and various Koli chiefs, who were influential in the region’s political landscape.

Later in 1635–36, Shahaji Raje Bhonsale is believed to have sought refuge at Mahuli with his wife Rajmata Jijabai and their young son, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. The fort was attacked by Khan Jaman, a Mughal commander, and, with no assistance from the nearby Portuguese authorities, Shahaji was forced to surrender.

By 1648, Shivaji Maharaj had begun his campaign of expansion, capturing several forts in the region, including Kalyan and Mahuli. The fort later fell to the Mughals in 1658, and under the Treaty of Purandar (1665) (a treaty signed between Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and Mughal general Jai Singh, requiring the cession of several forts), it had to be ceded. In 1670, Shivaji Maharaj launched another campaign to retake Mahuli. Although the initial attempt was unsuccessful, it resulted in the deaths of nearly a thousand Maratha soldiers, many from surrounding villages. In honour of their sacrifice, he is said to have conferred the Sonare surname upon the family of Manohardas Gaud, a local participant in the battle.

The Contest forKalyan and the Durgadi Fort

By the 1640s, Kalyan, a key settlement near the Ulhas River was also drawn into the wider conflicts. In 1636, the region had been ceded by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan to the Bijapur Sultanate, placing it nominally under Adil Shahi rule. However, the situation shifted quickly.

In 1648, Shivaji’s general Aabaji Sondev attacked Kalyan and captured it from the Adil Shahi forces. The Adil Shahi subhedar, Mullah Ahmad, was taken prisoner, and Sondev was appointed as the Maratha subhedar of Kalyan. Interestingly, it seems that Kalyan became recognised for its value not only in trade but also in naval operations and frontier defence. Just southwest of Kalyan, the Durgadi Fort gained prominence as a strategic outpost during this time. Perched above the creek, the fort served as a watchtower and defensive bastion. At its base lay Reti Bunder, a small landing site used for commerce and likely connected to early maritime activity. According to local accounts, it was at Reti Bunder that Shivaji established his first naval base in 1659.

However, Maratha control over Kalyan remained contested. In 1660, the Mughals reasserted their authority over the region and initiated a prolonged programme of fortification. Under Subhedar Matabar Khan, who served during the reign of Aurangzeb, significant efforts were made to rebuild and expand the town’s defences.

During this period, the conflict between the Mughals and the Marathas intensified, and Kalyan became one of the key points of military and political contention. Control of the town changed repeatedly over the decades. In 1683, a major offensive was launched by the Mughal general Bahadur Khan against Kalyan, which at the time was under Maratha control, led locally by the commander Tukoji. The Mughals succeeded in capturing the town, delivering a significant blow to Maratha influence in the area.

Yet the Maratha response was swift. In 1684, Sambhaji personally led a counter-attack to reclaim Kalyan. The Mughal garrison was defeated, and control of the town was restored to the Marathas. A renewed attempt by Bahadur Khan to recapture the fort followed soon after. On this occasion, the defence was overseen by Hambirrao Mohite, one of Sambhaji’s senior commanders. The Mughal forces were repelled, and Kalyan remained under Maratha control for the remainder of the decade.

The Siege of Ghodbunder and the Fall of the Portuguese

Following their consolidation over inland strongholds like Kalyan and Mahuli, the Marathas began turning their attention to the coastal forts still held by the Portuguese. Though their power had declined since the 17th century, the Portuguese still maintained a string of fortified positions in the north Konkan, including Thane, Bassein (Vasai), and Ghodbunder, which had withstood multiple attacks earlier by the Marathas.

In the 1730s, under the direction of Peshwa Baji Rao I, a sustained campaign was launched against the remaining Portuguese holdings in the region. The command of this operation was entrusted to Chimaji Appa, Baji Rao’s brother, who had gained a reputation for his effectiveness in siege warfare. Between 1736 and 1738, Maratha forces moved against a series of Portuguese fortifications. In 1737, Ghodbunder was besieged and taken after a concerted effort.

With the capture of Ghodbunder Fort in 1737, the Marathas under Chimaji Appa gained a critical foothold along the northern Konkan coast. This victory severed Portuguese communications across Salsette and placed pressure on the remaining coastal fortresses. The strategic attention of the Marathas now turned to Bassein (Vasai, Palghar district), which was their principal stronghold in the region. The subsequent siege of Bassein began in 1738 and lasted for several months. Portuguese forces, unable to receive effective reinforcements by land or sea, capitulated in May 1739. With the fall of Bassein, Portuguese power in north Konkan declined, and the Marathas took possession of the remaining forts and trading posts, including Thane.

Notably, Portuguese records indicate that, even prior to the final siege, there were signs of deteriorating control. In 1727, Lisbon dispatched an officer to inspect and propose reforms to their garrisons in Thane and the surrounding area. His report highlighted deep structural weaknesses: the absence of regular defence planning, disorganisation within the militia, and the poor condition of the cavalry, citing neglected animals and ineffective personnel. These assessments underscore how, by the 1730s, the Portuguese capacity to resist a sustained Maratha offensive had diminished considerably.

Thane under the Marathas from the French account

Following the fall of Bassein and the Maratha occupation of Thane, the region entered a period of relatively stable administration under Maratha control. A rare European account of this period survives in the writings of Anquetil du Perron, a French scholar and traveller who passed through Salsette and Thane in 1760 during a visit to the Kanheri and Elephanta caves. He expressed great admiration for Salsette. He wrote that “It was no wonder that it had tempted the Marathas, and if only the English could get hold of it, Bombay would be one of the best settlements of the east.”

Du Perron described Salsette as a place of strategic and natural appeal, remarking that it was “no wonder the Marathas had sought to possess it,” and noting that if the English obtained it, Bombay would become one of the most valuable settlements in the East.

His observations also highlight the degree of religious tolerance under Maratha rule. Christian communities were permitted to maintain their churches and hold processions. Du Perron records attending a Christian festival in Thane, where several thousand locals participated without interference. The native clergy remained active under a Vicar-General, and Hindu residents were said to observe the celebrations with respect.

Rise of the East India Company

Political pressures, however, remained as the Marathas extended their authority over the coastal tracts of Thane and Salsette (now part of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region). Their growing influence near Bombay (Mumbai), especially after the defeat of the Portuguese at Bassein (Vasai) in 1739, caused increasing unease among the English East India Company, which then held Bombay Island.

British apprehension was somewhat alleviated after the Third Battle of Panipat (1761), in which the Marathas suffered a massive defeat against Ahmad Shah Abdali. The loss weakened Maratha authority in northern India and triggered internal disarray within the confederacy. Peshwa Balaji Baji Rao died soon after hearing of the defeat, and his teenage son Madhavrao I succeeded him. Though Madhavrao later restored order, his death in 1772 reopened succession disputes.

The resulting power struggle set the stage for British intervention. After the death of Madhavrao, his uncle, Raghunathrao, claimed the office of Peshwa, asserting his right over Madhavrao’s younger brother, Narayanrao, who had been named successor. In 1773, Narayanrao was murdered under suspicious circumstances in Shaniwarwada, Pune. Although Raghunathrao assumed the title of Peshwa, he was soon opposed by a coalition of Maratha nobles known as the Barbhai Council, who installed Madhavrao II as Peshwa and declared Raghunathrao’s rule illegitimate.

Forced out of Pune, Raghunathrao sought the assistance of the English East India Company. In 1775, the Company signed the Treaty of Surat with him. Under this agreement, the British agreed to support his claim militarily, in return for the cession of Bassein (Vasai) and its dependencies, including revenue rights.

The treaty provoked immediate conflict with the dominant Maratha leadership. The ensuing war, known as the First Anglo-Maratha War (1775–1782), was fought across western India but yielded no clear victor. It ended with the Treaty of Salbai (1782), under which Bassein was returned to the Marathas, and Raghunathrao’s claim was abandoned. However, the British retained possession of Salsette, Elephanta, Hog Island, and Karanja. These locations were briefly occupied by the British but were soon retaken by Maratha commanders Haripant Phadke and Tukoji Holkar.

In 1802, during a renewed phase of Maratha infighting, Peshwa Baji Rao II (son of Raghunathrao) was defeated by the Holkar faction and fled Pune. He sought British support, and the resulting Treaty of Bassein (1802) which sought to formally subordinate the Peshwa to the East India Company. This arrangement provoked the Second Anglo-Maratha War (1803–1805), during which the British defeated the Scindias and Bhosales.

By 1817, the remnants of Maratha independence had weakened, but resistance continued. The final confrontation came with the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1818). This conflict was precipitated by a combination of factors, including unrest among the Pindaris (irregular cavalry groups supported by Maratha factions) and renewed hostilities from several Maratha rulers.

British forces launched a comprehensive campaign across central and western India. By early 1818, the Maratha Confederacy was dismantled, the Peshwa was formally deposed, and his dominions were annexed to British India.

In the same year, British troops occupied Ghodbunder Fort, a key coastal position in the Thane region that had earlier been held by both the Portuguese and the Marathas. The fort served briefly as the initial administrative centre of the newly formed Thane district. A District Collector was appointed at Thane, and the area was incorporated into the Bombay Presidency.

Colonial Period

Administrative Reorganizations

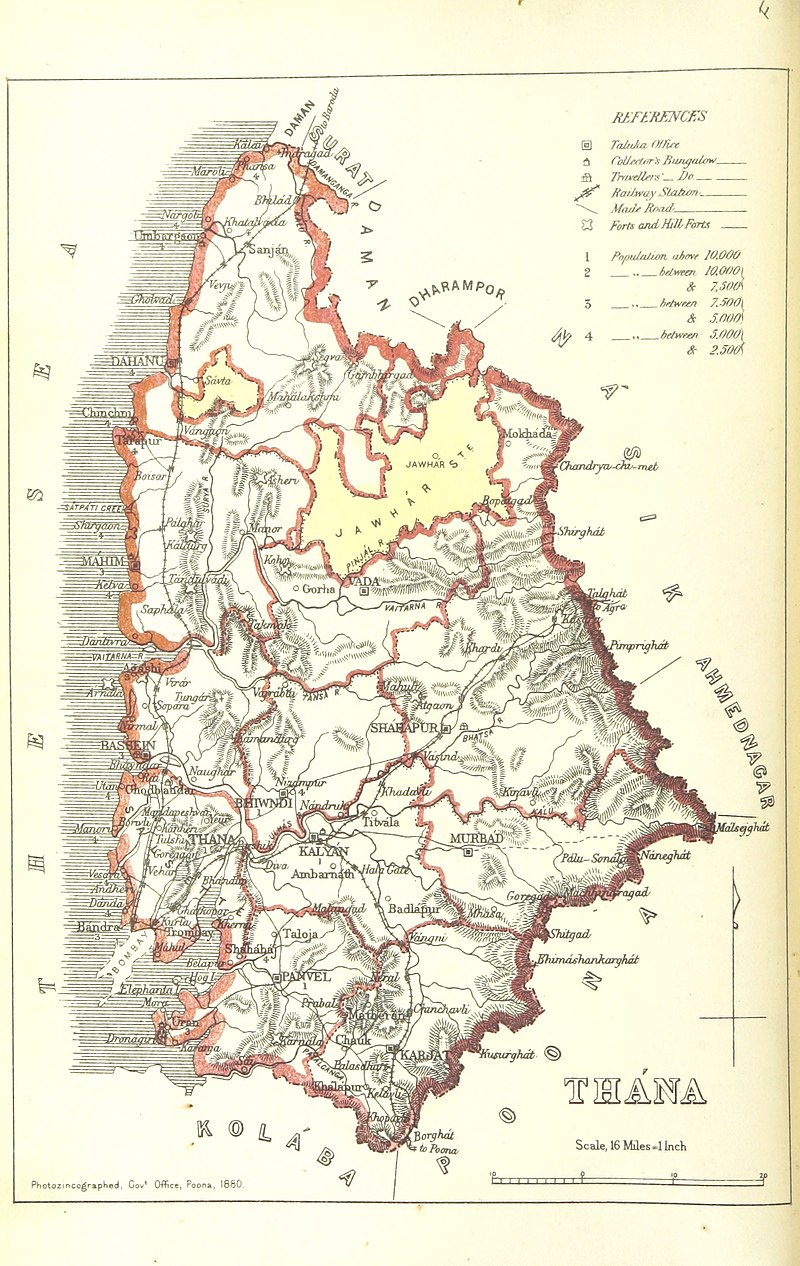

After coming under control of the British, a series of administrative changes and reorganizations took place in the region. These changes altered the boundaries, names, and functions of many subdivisions, which often came in response to growing urban influence from “Bombay” and the need for control over the rural lands of the present-day Thane district.

Between 1830 and 1833, Thane’s jurisdiction expanded to absorb areas from South Konkan, and by 1833, the region was officially named Thana District. In 1853, localities such as Pen, Roha, Mahad, Underi, and Revadanda (now in Raigad) were moved under the newly formed Kolaba Sub-Collectorate, although they technically remained under Thane’s administration for some years.

Between 1861 and 1866, Uran Mahal (Uran region, Raigad district) was separated from Salsette and placed under Panvel. Around the same period, several subdivisions were renamed:

- Kolvan was renamed Shahapur (Thane district),

- Nasrapur became Karjat (now in Raigad district).

Another major administrative shift came in the year 1871, when a taluka named South Salsette (much of which makes up the present-day Mumbai Suburban district) was created after carving out parts of the Bombay Island and Thane.

In the years following:

- Panvel, Uran, and Karanja were transferred to Kolaba (present-day Raigad) in 1883,

- Karjat followed in 1891.

Between 1917 and 1926, several reorganizations followed:

- A new mahal (subdivision) was created in 1917 with Bandra as its headquarters,

- In 1920, Salsette was split into North and South Salsette talukas,

- South Salsette was merged into the newly created Bombay Suburban District (present-day Mumbai Suburban),

- By 1923, North Salsette became a mahal under Kalyan taluka (Thane district), and in 1926, it was officially renamed Thane,

- Around the same time, Kelve-Mahim was renamed Palghar.

Famines in the Early 19th Century

During the early years of British governance, two major famines took place in the district, the first being in 1803-1804 and later in 1811-1812, with the latter being far more severe. The principal cause of both crises was the failure of the seasonal monsoon, which resulted in widespread crop failure and acute food shortages. The monsoon failure of 1812, in particular, is said to have led to severe distress among the local population. References to its extensive geographical impact is noted in the colonial district Gazetteer (1882), where it is described to have “wasted Marwar, Gujarat, Cutch, and [then] extended to Thana.”

During this period, large numbers of famine-affected people from neighboring regions, especially Marwar and Gujarat, arrived in the Thane district in search of food and shelter. Their arrival added to the existing pressures on local communities, who were already struggling to cope with the effects of crop failure and food scarcity.

The famine led to widespread distress across the district and forced many to flee towards Bombay (present-day Mumbai), which had a grain reserve expected to last fifteen months and became a major relief center. Reports from the time (cited in the 1882 Gazetteer) describe of how “the country was covered with bands of famine-stricken strangers from Marwar and Gujarat”, many of whom passed through or temporarily settled in Thane’s villages and towns. The British authorities debated whether “strangers should be prevented from landing and grain prevented from leaving the island.”

Some relief was provided by the colonial government, but it remained limited in reach. Much of the aid was directed towards Bombay, where administrative control was stronger. In Thane and its surrounding villages, food shortages continued. The district, already affected by failed crops, soon faced the added spread of disease. A brief description of the time is offered in the Gazetteer (1882), where it is written that “the wharfs and roads were lined with crowds of wretched half-starved objects; the eastern or land side of Bombay was strewn with the dead and dying.”

The mortality rate also rose drastically, with reports stating, “In spite of these efforts to save the famished strangers, the death rate rose from about fifteen to thirty or forty a day and sometimes to over a hundred.” This crisis, in many ways, left a deep impact on Thane district; it set in motion a movement, which altered the population of the district. New settlements appeared along roads and markets. Some villages saw sharp declines, while others grew with the arrival of displaced families.

Uprisings by the Kolis and Bhils

In the decades that followed, Thane district continued to experience social and administrative shifts under British control. In the Sahyadri hills, where Koli communities had long held roles in policing, land management, and village leadership, these changes led to growing discontent. Forts were dismantled, wages for local service were reduced, and existing authority structures were replaced by new forms of oversight.

In 1828, this discontent turned into open resistance. Ramji Bhangare, also known as Ramji Patil, was Patil of Devgaon and had served as a Jemadar in the British Indian Army. That year, during the Ramoshi revolt in Satara, he left his post and began organising raids across parts of Thane and the Konkan region. Working with Govind Rao Khare, he targeted revenue stations and supply routes, using the forests and hill paths to move between settlements. (It is important to note here that this was not Ramji’s first act of resistance. Years earlier, he and his uncle Valoji Bhangare had carried out raids over local land disputes to defy the Peshwas and their policies. In both cases, his actions reflected the concerns of village communities facing changes in control over land and authority.)

By 1830, the Bhil community had also become part of the movement. The raids, carried out through forest routes and hill passes, became more frequent and organised. In response, British forces were deployed across the region. Raids continued for several months before Ramji and several of his followers were captured and imprisoned in Ahmednagar (present-day Ahilyanagar).

Defiance for Holi

Acts of resistance continued into the 1850s. In 1853, an order prohibiting the digging of pits for Holi fires on public roads led to unrest in Thane town. In protest, Hindu merchants closed their shops. In response, colonial authorities posted guards and forcibly reopened them.

The First War for Independence, 1857

In the later years, the broader currents of the 1857 Revolt, also called the First War of Independence, were felt in Thane as well. Although no major uprising seemed to have occurred in Thane during the revolt of 1857, the district did not go unnoticed. As the rebellion spread across parts of North and Central India, colonial authorities in the Bombay Presidency began to monitor regions more closely, especially those with ties, however indirect, to rebel leadership.

Thane, then, was among one of these regions. One of the leaders of the revolt, Nana Saheb II, also known as Dhondu Pant, had been born in Vangaon, near Karjat, which was then part of Thane district. Though he was mostly active in Kanpur, his connection to the region drew attention. As the village came under closer watch, his relative, Ragho Vishvanath, was arrested for inciting unrest and brought to Thane jail.

In the months that followed, new orders were put in place. Newspaper editors were warned not to publish reports of mutinies without approval. Civilians were required to register or surrender their arms. Armed groups travelling through the district were disarmed. Restrictions were imposed on the import of weapons and related materials. Passports were made mandatory for travellers, and the landing of Arabs at ports was temporarily suspended.

Income Tax Resistance

In the years that followed, British efforts to consolidate control in the district increasingly took administrative and fiscal forms. One such measure was the introduction of income tax in 1860. Its establishment prompted immediate unrest in Thane district.

The response was widespread. In towns such as Thane, Kalyan, Bhiwandi, and Shahapur, it is noted that residents refused to accept the new tax forms. In some places, they were discarded in protest. The most organised resistance took place in Bassein (now Vasai, Palghar district), then still part of Thane district. There, members of the mercantile community, led by traders like Seth Govardhan Das, mobilised against the new policy. On 6 December 1860, thousands gathered in public spaces near Vasai Fort and the Collectorate building. The forms were again publicly thrown aside, and objections were voiced over what many saw as an unjust imposition.

The Deputy Collector, Mr. Hunter, was dispatched to manage the situation. On arrival, he was confronted by protestors, including peasants and Kolis, who surrounded him and demanded he hear their concerns. A brief scuffle followed, and Hunter eventually withdrew with assistance from his clerk.

Govardhan Das was arrested, sentenced to a month in prison, and fined Rs 400. Though the tax remained, the protests marked a moment of public and coordinated resistance to new forms of colonial authority in the district.

Local Robberies

One of the methods employed by locals to contest British control and assert local autonomy was through acts of robbery. Although a criminal activity, perhaps it was perceived as a way of challenging colonial administration and its oppressive policies.

In the later decades of the 19th century, several such acts were recorded across the district. In 1874, Honia Bhagoji Kenglia, a Koli from Jambhulpada (Raigad district), emerged as the leader of a group that operated in and around Thane. His movements were quick, his methods difficult to trace. A special police unit was raised to pursue him, and a European officer was assigned to lead the effort. For nearly two years, the pursuit continued across villages, forested tracts, and hilly passes. Each attempt to locate him ended without success.

Eventually, on 15 August 1876, Honia was captured near Nandgaon in Karjat, then part of Thane district, and sentenced to life imprisonment.

A year later, in 1877, the campaign led by Vasudev Balwant Phadke reached the district. Phadke, already active in the Pune region, had begun a series of raids targeting government treasuries and moneylenders. In Thane, his followers carried out several such acts, including the looting of a Brahmin merchant’s residence in Panvel (which now lies in the Raigad district).

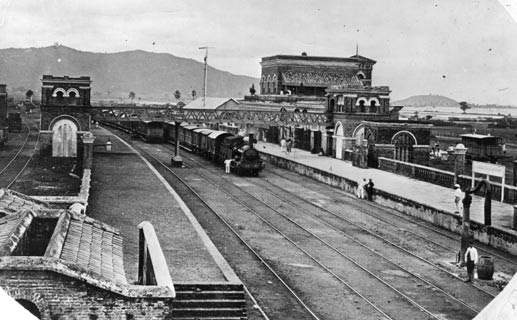

Thane Terminus and the First Railway in India

Even as new pressures and tensions unfolded across the district in the mid-19th century, Thane also became the site of a major development in the subcontinent’s transport history. On 16 April 1853, a passenger train departed from Bori Bunder (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus) in Mumbai City and arrived at the newly inaugurated terminus in Thane, covering a distance of approximately 34 km. The train carried around 400 passengers and marked the beginning of passenger railway service in the region.

Several months earlier, on 18 November 1852, a trial run had been conducted along the same stretch. Using Lord Falkland, the first steam engine brought to Bombay, the Directors and Engineers of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway travelled from near Bori Bunder to Parsik Point in Thane. In the absence of formal carriages, modified goods trucks were used.

The official journey in April 1853 was a grand affair. A decorated platform was prepared at Bori Bunder. In Thane, tents were erected for arriving passengers. Police were deployed along the final mile of track to manage the crowd. A short address was given by Chief Engineer James J. Berkeley, who noted the work done by local labourers and support staff.

In the years that followed, the railways expanded steadily across the Bombay Presidency. Today, Thane remains one of the busiest stations on the Central and Trans-Harbour suburban railway network, connecting the city to Mumbai, Navi Mumbai, and beyond.

Decline of Thane’s Maritime Economy Under British Rule

While the opening of the railways marked a new phase of connectivity, it also coincided with broader economic shifts that altered Thane’s position in the region. As noted earlier, Thane had long maintained a strong maritime trade network and while this role gradually receded in prominence, it did not disappear entirely. Well into the early 1800s, goods such as grain, salt, timber, and stone moved regularly through Thane’s creeks and roads.

Over time, however, this role began to shrink. As the “Bombay” of the British rose under their rule, it increasingly reordered the region’s economic geography. Districts on the city’s periphery, including Thane, were gradually redefined as suppliers to the urban centre. This shift was particularly visible on Salsette Island, which constitutes parts of the present-day Thane and Mumbai Suburban district. In a 1914 report, the Bombay Development Committee described Salsette as integral to the city’s future, where it is written that “Salsette development is so closely connected with the development of Bombay that we should like to call attention to certain matters affecting Salsette, since that island will after all be part of the Bombay of the future.”

While the report was primarily addressed to what is now the Mumbai Suburban district, it reflected a wider trend. Thane’s economy, which was once oriented toward regional exchange, became increasingly tied to the demands of the metropolitan port. According to the Bombay Gazetteer (1882), internal trade in Thane grew substantially during this period: imports rose from ₹411 lakh in 1805 to ₹2,357 lakh in 1881, and exports from ₹830 lakh to ₹2,921 lakh. Yet this growth is noted to have primarily served the Bombay market, particularly its need for raw materials, lime, stone, sand, and agricultural produce, rather than broader trade networks.

As this shift deepened, Thane’s maritime and overland commercial roles diminished. Local shipping declined. Freight movement through creeks and cart-routes was reduced. Porters, cartmen, and small seamen who once worked between the hills and coast saw their livelihoods gradually fade.

India’s Struggle for Independence

In the early decades of the 20th century, Thane district began to more visibly register its presence in the growing movement for Indian self-rule. Local leaders, particularly from Bhiwandi and Kalyan, emerged as key participants in campaigns for political reform and national mobilisation.

One of the notable figures during this period was Prabhakar Bhaskar Kunte, a lawyer from Bhiwandi. He played a significant role in the local organisation of Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s Home Rule campaign, helping raise funds and coordinate public engagement across the district. In early 1918, Kunte was involved in circulating leaflets and correspondence across Bhiwandi and Wada, urging contributions toward the Home Rule League’s efforts to support Tilak’s tour of England. Through these appeals, a total of ₹5,001 was raised.

On 10 March 1918, after concluding his program in Panvel, Lokmanya Tilak arrived in Kalyan and was formally presented with the fund. Later that evening, he travelled to Bhiwandi, where a public gathering had been organised. A reception committee, led by Kunte and Narayanrao Jog and presided over by Mayor Alisaheb Faki, had been formed in anticipation of his arrival.

Tilak’s visit left a lasting impression. In the months that followed, branches of the Home Rule League were established across the district in Thane, Bhiwandi, Kalyan, Khardi, and Bhayander, signalling a wave of political consciousness that had begun to take firm root in the region.

Ambernath Ordnance Factory

In the final years of British rule, even as political movements intensified across India, the subcontinent was drawn without choice into the demands of the Second World War. While much of the fighting took place elsewhere, the war brought with it new pressures, resources were diverted, industries restructured, and people conscripted into labour or service.

It was during this period that the Ambernath Ordnance Factory was established in as the name indicates, the Ambernath area of Thane district. Built under the direction of the colonial government’s Ordnance Factory Board, it was intended to support the British war effort by producing ammunition, explosives, and other military equipment.

While its operations served colonial military priorities at the time, the factory would go on to play a role in post-independence industrialisation. In the years that followed, Ambernath remained a centre for defence production, and became part of a growing cluster of state-run industries in the region.

Post-Independence

After India gained independence in 1947, Thane district underwent several important territorial and administrative changes. One of the first was the integration of the princely state of Jawhar in 1949. Like other princely states, Jawhar was given the option to join the country, and its ruler chose to accede to India. The state was merged into Thane district and became a separate taluka (sub-district). Today, this area forms part of the Palghar district.

In 1956, further changes took place when the boundaries of Greater Bombay (now Mumbai) were expanded northward. As part of this reorganisation, 27 villages and 8 towns from the Borivali taluka (now in Mumbai suburban district), along with one town and one village from the Thana taluka, were transferred out of Thane and added to the Bombay Suburban district. More changes followed in 1960, when the bilingual Bombay State was split to form the states of Maharashtra and Gujarat. At that time, the taluka of Umbargaon, located on the northern edge of Thane, was divided: 47 villages and 3 towns were transferred to Surat district in Gujarat. The remaining 27 villages remained in Maharashtra, first under Dahanu taluka and later reorganised into a separate administrative unit called Talasari in 1961.

In 1969, Kalyan taluka was split into two separate talukas, Kalyan and Ulhasnagar, to better manage the growing population in the area. A few years earlier, in 1945, 33 villages had been temporarily transferred from the Mumbai Suburban district to Thane, but 14 of these were returned in 1946 with the creation of the Aarey Milk Colony.

A major reorganisation occurred in 2014, when the northern part of Thane district was carved out to form a new district: Palghar. This new district included the talukas of Palghar, Dahanu, Talasari, Vikramgad, Jawhar, Mokhada, and Wada. Today, Thane district consists of the following talukas: Thane, Kalyan, Ulhasnagar, Ambernath, Bhiwandi, Murbad, and Shahapur.

Siemens Kalwa factory

Alongside administrative restructuring, Thane also witnessed notable industrial growth in the post-independence period. Kalwa, in particular, emerged as a key industrial hub. In 1960, Siemens, a European technology firm specializing in infrastructure and transport solutions, established its first Indian factory in Kalwa. The facility, among the oldest of its kind in the country. The facility became one of the company’s earliest manufacturing units in India and has remained operational since.

Partition Refugees in Ulhasnagar

The years following independence were marked not only by administrative change, but also by the effects of partition and displacement. Like many other districts across western India, Thane became a site of refugee rehabilitation. One of the most significant resettlements took place in Ulhasnagar (a town that would emerge from the upheavals of 1947).

After the partition of India, large numbers of Hindu and Sikh refugees from Sindh (now in Pakistan) arrived in Bombay Presidency. With limited resources and a shortage of housing, many spent their early days sheltering in makeshift arrangements.

It was only when British army barracks in Kalyan were vacated that a more formal solution took shape. Five empty barracks, formerly used by soldiers, were made available to the new arrivals. Families rushed to occupy what space they could, often with twelve or more families sharing a single structure. Curtains fashioned from old saris and gunny sacks separated one living unit from another.

From this beginning, the town of Ulhasnagar was born, its name, meaning “City of Happiness,” offering a quiet irony amid the realities of post-partition displacement. Many of the Sindhi families had arrived as former landowners and traders; in Ulhasnagar, they found themselves starting from scratch.