WASHIM

Language

Last updated on 22 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Language has played a central role in shaping India’s social and political landscape, particularly during key moments such as the States Reorganization Act of 1956, which restructured state boundaries based on linguistic identity. That same year, the Washim region was transferred from Madhya Pradesh to Bombay State. Later, in 1960, Bombay State was divided to form the modern states of Maharashtra and Gujarat, each defined by the dominant language spoken within its borders. Eventually, in 1998, Washim was carved out from the larger Akola district and established as an independent administrative district.

The most widely spoken language in Washim today is Marathi, followed by Hindi, Urdu, Varhadi, and Banjari. In addition to these, other varieties such as Wadari and Banjara are also spoken by groups residing within the district.

Linguistic Landscape of the District

The linguistic landscape of Washim reflects not only its geographic location but also its historical ties. Historically, Washim was part of the Berar region, which remained under the Nizam of Hyderabad until 1903, after which it was incorporated into the Central Provinces (present-day Madhya Pradesh) under British colonial rule. These shifts have contributed to the presence of Telugu, Urdu, and Hindi speakers in the area. Varhadi-Nagpuri, a language variety spoken across the Varhad (also known as the Vidarbha) region, is also widely used in Washim.

Remarkably, the 2011 Census of India data reveals that several languages are spoken as mother tongues in Washim district. It is recorded that the district had a total population of approximately 11.97 lakh (11,97,160). Of this population, 75.88% reported Marathi as their first language. This was followed by Banjari (8.40%), Urdu (8.26%), and Hindi (5.16%). Other languages spoken as mother tongues included Marwari (0.82%), Vadari/Wadari (0.45%), Sindhi (0.20%), Paradhi (0.13%), Gujarati (0.12%), and Telugu (0.11%).

Language Varieties in the District

Banjari

Banjari, also known as Lambani, Lambadi, Gormati, or Lamani, is a language spoken by a large community spread across various regions of India. It is spoken by the Banjara or Laman community, originally from the Mewar region of Rajasthan. Over time, this community migrated to various parts of India in search of trade and employment, leading to a wide geographical spread. Today, its speakers can be found in Maharashtra, Karnataka, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, and West Bengal, with smaller populations in other states.

In Washim district, the language holds a significant place. According to the 2011 Census of India, with a total of 1,00,537 speakers, making it the second most widely spoken language in the district after Marathi. The district is also home to Poharadevi, a key yatra site for the community, which adds to its cultural significance for its speakers and community members.

Banjari does not have a native script (original writing system), which has shaped how the language is used and preserved. Instead of writing in their own script, speakers have adapted the writing systems of surrounding regional languages. In Maharashtra, for example, they use the Devanagari script (used for Marathi and Hindi), while in Karnataka, the Kannada script is used.

Sounds in Banjari (Phonology)

Banjari has a simple yet distinct sound system. It uses six vowels—a, e, i, o, u, along with their longer forms like ā and ī. However, long vowels are generally not used at the end of words. The language has about 32 consonants, many of which are similar to those found in Marathi. Notably, some Marathi sounds, such as "थ" (/th/ with a breathy sound), are absent in Banjari. Nasal sounds, like the "ng" in song, are common, but changing them doesn’t usually alter a word’s meaning. Aspirated consonants those pronounced with an extra puff of air tend to appear mostly at the beginning of words. This combination of familiar and unique sounds gives Banjari its distinctive phonological character.

Word Formation in Banjari (Morphology)

Banjari shows a fascinating blend of its own vocabulary and forms borrowed from languages like Marathi and Hindi. This blending is most noticeable in everyday words, terms for family, the body, colours, food, and numbers. Many of these look and sound quite similar across all three languages, showing how close contact and migration have shaped the language.

In terms of kinship and pronouns, Banjari uses words that are nearly identical to Marathi and Hindi. For instance, ‘sāsu’ means ‘mother-in-law’ in all three. The word for ‘father’ in Banjari, ‘bā’, is closely related to ‘bābā’ or ‘vadil’ in Marathi and ‘pitāji’ in Hindi. Even the second-person singular pronoun ‘tu’ is the same across the three languages.

|

Banjari |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

sāsu |

sāsu |

sās |

mother-in-law |

|

bā |

bābā / vadil |

pitāji |

father |

|

dhani |

dhani / navarā |

pati |

husband |

|

tu |

tu |

tum |

you |

Words for body parts follow a similar pattern. In many cases, there is almost no difference in form, for example, dāt for ‘tooth’, hāt for ‘hand’, and gāl for ‘cheek’ are the same in Banjari and Marathi, and very close in Hindi too. This suggests a strong set of shared roots or long-term borrowing between the languages.

|

Banjari |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

hot |

oth |

hoth |

lips |

|

dāt |

dāt |

dānt |

tooth |

|

hāt |

hāt |

hānth |

hand |

|

gāl |

gāl |

gāl |

cheek |

|

anguthā |

angathā |

anguthā |

thumb |

|

pet |

Pot |

pet |

stomach |

|

kapāɭo |

kapāɭ |

sir |

forehead |

|

ṭāng |

Pāy |

ṭāng |

leg |

The same goes for colours. Banjari’s ‘haro’ (green) and ‘niɭo’ (blue) are very close to ‘hirwā’ and ‘niɭā’ in Marathi and ‘harā’, ‘nilā’ in Hindi. The small vowel differences at the end don’t change the meaning, but they do reflect local phonological patterns.

|

Banjari |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

haro |

hirwā |

harā |

green |

|

niɭo |

niɭā |

nilā |

blue |

Food vocabulary is especially rich in borrowed or shared forms. Words like kāndo (onion), seb (apple), and santra (orange) are consistent across the three languages. A few items, like angur (grapes), also show influence from Marathi, which uses draksha, reflecting regional variety even within a shared root.

|

Banjari |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

kāndo |

kāndā |

pyāj |

onion |

|

muɭo |

muɭā |

muɭi |

radish |

|

angur |

drakshā |

angur |

grapes |

|

santra |

santra |

santra |

orange |

|

seb |

sapharchandǝ |

seb |

apple |

|

āṭo |

pith |

āṭā |

flour |

|

nimbu |

limbu |

nimbu |

lemon |

|

ālu |

baṭāṭā |

ālu |

potato |

|

bhindā |

bhendi |

bhindi |

lady finger |

In numbers too, Banjari keeps very close to both Marathi and Hindi, particularly for the basic counting numbers. Words like ‘ek’ (one), ‘ʧār’ (four), and ‘sāt’ (seven) are essentially the same. For numbers above twenty, Banjari uses a compounding system - ‘wisan ek’ for twenty-one, ‘wisan di’ for twenty-two, and so on.

|

Banjari |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

ek |

ek |

ek |

one |

|

ʧār |

ʧār |

ʧār |

four |

|

nav |

nau |

nau |

nine |

|

sāt |

sāt |

sāt |

seven |

|

das |

dahā |

das |

ten |

|

sǝu |

shambhar |

sǝu |

hundred |

|

vis |

vis |

bis |

twenty |

Ordinal numbers are also easy to form. In Banjari, adding -ne to a cardinal number makes it ordinal. For instance, ‘ekne’ is ‘first’, ‘dine’ is second, and ‘tinne’ is ‘third’. General vocabulary also reflects a strong Marathi and Hindi influence, with many everyday nouns being identical or nearly so.

|

Banjari |

Marathi |

Hindi |

Meaning in English |

|

phul |

phul |

phul |

flower |

|

pankhā |

pankhā |

pankhā |

fan |

|

pāɳi |

pāɳi |

pāni |

water |

|

ābhaɭ / ābhaɭo |

ābhaɭ |

ākāsh |

sky |

|

mor |

mor |

mor |

peacock |

|

ghodā |

ghodā |

ghodā |

horse |

|

somwār |

somwār |

somwār |

Monday |

|

rāt |

rātrǝ |

rāt |

night |

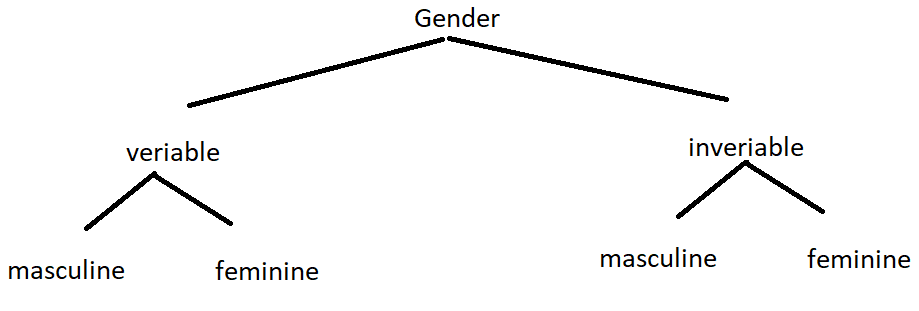

Banjari nouns follow a pattern that shows gender (male or female), number (singular or plural), and case (how the noun functions in the sentence, like subject or object). There is no third gender category (neuter), which is different from many other regional languages.

In Banjari, the general form of a noun is: Noun stem + gender + number + case suffix (case suffix = small ending added to show the noun's role in a sentence).

Some nouns use the same root but change the ending vowel to show gender. For example:

|

Masculine |

Feminine |

Meaning in English |

|

ghodā |

ghodi |

horse |

|

betā |

beti |

boy/girl |

In Banjari, plural forms (more than one) are often shown through the verb or number word in the sentence, rather than changing the noun itself. This is especially true when the noun is the subject. In such cases, the noun form stays the same, and the listener understands it is plural based on context.

In other cases, Banjari uses three ways to show plurals:

- Adding a suffix (a small word-ending)

- Repeating the noun (called reduplication)

- Removing part of the original word

|

Singular |

Plural |

Method Used |

Gloss |

|

betā |

betābetā |

Reduplication |

boy → boys |

|

sāsu |

sāsuo |

Adds suffix ‘-o’ |

aunt → aunts |

|

telǝwālo |

telǝwāl |

Ending removed |

oilman → oilmen |

Banjari also uses common endings from other languages to form agent words (called agentive suffixes). For example, wala (male) and wali (female) are added to describe someone doing a job or activity—like telwala = “oil seller.”

Pronouns (words like I, you, they) in Banjari don’t show gender, but they do show singular/plural. The basic structure is: Pronoun Stem + Case Suffix.

|

Singular |

Plural |

Meaning in English |

|

ma |

ham |

I – we |

|

tu |

tam |

you – you all |

Banjari also uses ekmek for “each other,” just like in Marathi. This shows how closely the two languages are related in structure.

Verbs in Banjari change depending on who is doing the action and when it happens. This process is called conjugation (changing a verb to show tense, number, or gender). For example, jo means “to go,” but its form will change depending on the speaker or time.

|

Base Verb |

Present Tense (3rd person) |

Explanation |

|

jo |

jāwa |

“he/she goes” – adds ‘w’ |

|

baga |

bagawa |

“throws” – adds ‘w’ |

|

lu |

luwa |

“wipes” – adds ‘w’ |

In the past tense, Banjari uses -y after verbs that end in a, u, or o:

|

Verb |

Past Tense |

Meaning |

|

ā |

āy, āyo |

came |

|

so |

soy, soyo |

slept |

|

cu |

cuy, cuyo |

leaked |

There are few compound verbs in Banjari such as:

|

Normal verb |

Compound verb |

Meaning in English |

|

Jo (to go) |

pad jo wad jo so jo dhās jo le jo |

To fall down To fly away To fall asleep To run away To take away |

|

lā (to take/ to accept) |

Ker lā rām lā |

To do To play |

|

dā (to give) |

bhānd da |

To tie |

Wadari

Wadari is a language variety spoken by the Wadar community, which is spread across several parts of Maharashtra, including Satara, Sangli, Karad, Washim, and Solapur (particularly Pandharpur). The community also has a presence in Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Odisha. This wide distribution is noted by Laxman Chavan in the Languages of Maharashtra volume of the People’s Linguistic Survey of India (2017), where he offers insight into the linguistic and social history of the Wadars. In Washim, according to the 2011 Census of India, Wadari was spoken as a mother tongue by 0.45% of the population, which amounts to 5,419 speakers.

The community is known by different names in these regions such as Odde, Wadde, Wadu, Wadar, Wadr, and Ur. The name Odde in particular, it is said, suggests that this community may have come from Odisha, while the word ‘Wadu' means ‘those who shape stones' in Kannada. On the contrary, a few believe that they originated from Andhra Pradesh because the Wadari language variety has a strong Telugu influence.

Vocabulary

The language contains many words that are distinct and not directly traceable to surrounding regional languages. These terms reflect the community’s independent linguistic identity and longstanding usage.

|

Wadari Word |

Transliteration |

Pronunciation |

English Meaning |

|

मब्बाड |

mabbaad |

məbbaɖ |

Father |

|

व्हसम |

vhasam |

vhəsəm |

Yellow |

Some Wadari words, however, have come from contact with other languages. In Maharashtra, Marathi has had a strong influence on Wadari. Some of these words are used directly, while others have been adapted in form or shortened in daily use. Few examples are as follows:

|

Wadari Word |

Transliteration |

Pronunciation |

Marathi Source |

Marathi Transliteration |

English Meaning |

|

वहिनी |

vahini |

vəhini: |

वहिनी |

vahinī |

Brother’s wife |

|

नारिगी |

naarigi |

narigi: |

नारिंगी रंग |

nāriṅgī raṅg |

Orange colour |

|

आहोटी |

aahoti |

a:hoʈi: |

ओहोटी |

ohaṭī |

Low tide |

One example of this type of change is the word नारिगी (naarigi), which means orange in Wadari. It likely comes from the Marathi phrase नारिंगी रंग (nāriṅgī raṅg), meaning orange colour. This process of word formation, where part of a longer phrase is dropped, and only the beginning is kept—is what linguists call back-clipping. Here’s how the change may have happened: नारिंगी रंग (nāriṅgī raṅg) → नारिगी (naarigi).

Back-clipping is common in everyday speech, especially when longer expressions are shortened for ease or efficiency in conversation.

Varhadi

Varhadi is a language variety that is mainly spoken in the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra, in districts such as Amravati, Akola, Buldhana, Washim, and Yavatmal. This region is sometimes called ‘Varhad Pradesh’, as noted by Deepdhwaja Kosode (2017). The Vidarbha region has a long history, and is even mentioned in ancient texts like the Mahabharata as a legendary kingdom.

Varhadi is well known for a number of phonetic (sound) changes, differences in vocabulary, and grammatical features that make it distinct from other language varieties.

Sound Changes

One of the most noticeable features of Varhadi is that the sound “ल” (la) is often replaced with “ड” (da). For example the word ‘बोल (bol)’ which means ‘to speak’ in English becomes बोड (bod) in Varhadi. This change is quite common and perhaps gives Varhadi speech a smoother and simpler sound in everyday use.

Another interesting feature, noted in the Amravati District Gazetteer (1968), is that long vowels, especially at the ends of words, are often shortened in Varhadi speech. This sound change perhaps makes words comparatively simpler and quicker to say. For example:

|

Varhadi Word |

Transliteration |

English Meaning |

|

जोल |

jol |

Near |

|

उडोला |

udola |

Squandered |

These forms come from longer versions जवळ (javal) and उडविला (udavila), but the final vowels are shortened in daily speech. In many words, the vowel ‘a’ is used instead of ‘e’, especially in future tense verbs and some nouns. This can be seen in examples like:

|

Varhadi Word |

Transliteration |

English Meaning |

|

संगटला |

sangatla |

It was said |

|

असल |

asal |

I shall be |

|

डुकर |

dukra |

Pig |

There is also a pattern where ‘i’ and ‘e’ are replaced by ‘va’ in some words. This results in forms like:

|

Varhadi Word |

Transliteration |

English Meaning |

|

डेल्ला |

della |

Given |

|

वेक |

vek |

One |

In addition, the sound ‘v’ is often weak or missing when it comes before ‘i’ and ‘e’. Because of this, words like vistav, vis, and vel are often heard in shortened forms:

|

Varhadi Word |

Transliteration |

English Meaning |

|

इस्तो |

isto |

Fire |

|

इस |

is |

Twenty |

|

येल |

yel |

Time |

These examples show how Varhadi simplifies pronunciation in everyday speech, making it distinct from other varieties. Such sound changes are a key part of what gives Varhadi its unique character.

Vocabulary

Aside from pronunciation, Varhadi also has vocabulary that is both familiar and region-specific. Speakers of Varhadi use some words that are common across Marathi and Hindi, and some that are specific to the region. For example, आलू (ālu) for potato is used in both Varhadi and Hindi, while सिगल (sigal), meaning cup or container, is more region-specific.

|

Varhadi (Marathi) |

Transliteration |

English Meaning |

|

आलू |

ālu |

Potato |

|

सिगल |

sigal |

Cup, container |

|

गिलास |

gilās |

Glass |

Family terms in Varhadi reflect close relationships and often have local variants. Some of these, such as porgi and porga, are also used in other parts of Maharashtra, but forms like katti and katta show regional variation.

|

Varhadi (Marathi) |

Transliteration |

English Meaning |

|

पोरगी / कट्टी |

porgi / katti |

Daughter |

|

पोरगा / कट्टा |

porga / katta |

Son |

|

माज / मा |

maj / mā |

Mother |

|

बाप / बा |

bāp / bā |

Father |

The terms for body parts in Varhadi, in many ways, reflect its unique phonetic features. For example, टेकुर (head) and केपज (forehead) highlight the differences from standard pronunciations of similar words in other regions.

|

Varhadi (Marathi) |

Transliteration |

English Meaning |

|

टेकूरं / डोस्कं |

tekur / doske |

Head |

|

कपाय |

kepaj |

Forehead |

|

डोये |

doye |

Eyes |

Colour terms in Varhadi also differ slightly from forms that one can usually find in Hindi or Marathi, often showing simplified or altered sounds.

|

Varhadi (Marathi) |

Transliteration |

English Meaning |

|

पिव्वा |

pivva |

Yellow |

|

निया |

niya |

Blue |

|

काया |

kaya |

Black |

Proverbs in Varhadi

Proverbs are an important part of oral tradition. They carry life lessons, humor, and cultural values, passed down through generations. These sayings often reflect practical wisdom and comment on everyday situations that are spoken in Varhadi.

|

Varhadi (Marathi) |

Transliteration |

English Meaning |

|

पळाले ना पोसले आणि फुकट डोळे वसवले |

paḷale na posale āṇi phukṭa ḍole vasayle |

Showing off without doing any real work |

|

घराचं करायचं देवाचं आणि बाहेरचं चोई सिवाय |

gharācā karate devācā āṇi bāherācīle coyī sivā |

Doing useless or irrelevant work |

Sources

Census of India. 2011. Language Atlas of India. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India.https://language.census.gov.in/showAtlas

Deepdhwaja Kosode. 2017. Varhadi. In G.N. Devy and Arun Jakhade (eds.). The Languages of Maharashtra, People’s Linguistic Survey of India Vol. 17, part 2. Orient Blackswan: Hyderabad.

George Yule. 2020. The Study of Language. 7th ed. Cambridge University Press.

Jayashree Patil. 2014. Study of the Phonology of Lamani Language Spoken in Pune (Master's thesis). Deccan College Post-Graduate & Research Institute, Pune.

Laxman Chavan. 2017. Wadari. In G.N. Devy and Arun Jakhade (eds.). The Languages of Maharashtra, People’s Linguistic Survey of India Vol. 17, part 2. Orient Blackswan: Hyderabad.

Luke Koshi. 2016. Explainer: The reorganization of states in India and why it happened. The News Minute.https://www.thenewsminute.com/news/explainer…

Maharashtra State Gazetteers. 1968. Amravati District. Directorate of Government Printing, Stationary & Publications, Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai.

Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. 2011. Census of India 2011: Language Census. Government of India..https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/ca…

R.L. Trail. 1968. Lamani: Phonology, Grammar and Lexicon (Doctoral dissertation). University of Poona.https://www.sil.org/resources/archives/9360

Last updated on 22 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.