Contents

- Crop Cultivation

- Agricultural Communities

- Types of Farming

- Cotton Cultivation

- Cultivation Practices and Techniques

- The Shift in Cotton Varieties: From Traditional to High-Yielding Seeds

- Moving to Genetically Modified Cotton: The Case of Bt Cotton

- Jowar Cultivation

- Institutional Infrastructure

- Market Structure: APMCs

- List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

- Farmers Issues

- Graphs

- Irrigation

- A. No. of Projects

- B. No. of Ponds/Vilage Lakes and Storage Dams

- C. Irrigation Beneficiary Area vs Irrigated Area

- D. Share of Beneficiary Area Irrigated

- E. Tubewells and Pumps Installed In The Year

- F. Irrigation and Water Pumping Facilities

- Cropping Metrics

- A. Share in Total Holdings

- B. Cultivated Area (With Components)

- C. Gross Cropped Area (Irrigated + Unirrigated)

- D. Share of Cropped Area Irrigated

- E. Distribution of Chemical Fertilizers

- Land Use and Credit

- A. Area of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- B. Size Groups' Share in Total Agricultural Land Holdings Area

- C. No. of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- D. Size Groups' Share in Total No. of Agricultural Land Holdings

- E. Agricultural Lending

- F. Agricultural Credit as a share of Total Credit

- Sources

AMRAVATI

Agriculture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

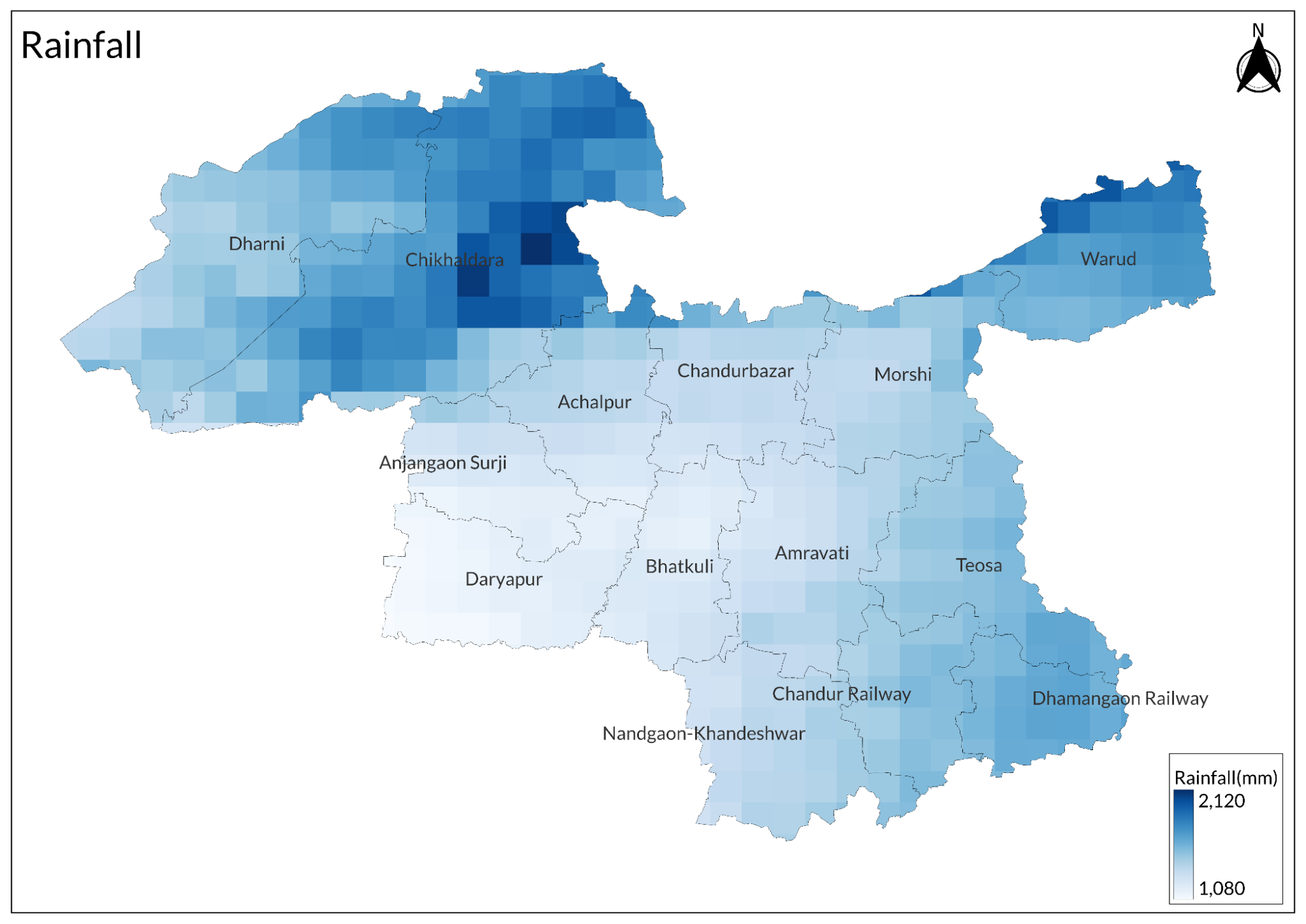

Agriculture in Amravati, located in Maharashtra’s Vidarbha region, plays a crucial role in the local economy. As per the NABARD Potential Linked Credit Plan (2023-24), out of the district’s total 12.21 lakh hectares, 7.81 lakh hectares are cultivable. The region is served by three major rivers, Tapi, Purna, and Wardha, according to the Central Ground Water Board report.

Despite these natural resources, Amravati has been grappling with severe agrarian distress. A recent report by The Times of India underscores the alarming toll of farmer suicides in the district. The newspaper reported that 76% of the over 1,000 farmer suicides in Amravati from 2021 to 2023 were attributed to agrarian distress (figures that are said to be significantly higher than those in Yavatmal, which is often referred to as the “suicide capital of Maharashtra.”) Debt, coupled with other pressures, has led to an escalating crisis, underlining the urgent need for intervention in the region.

Crop Cultivation

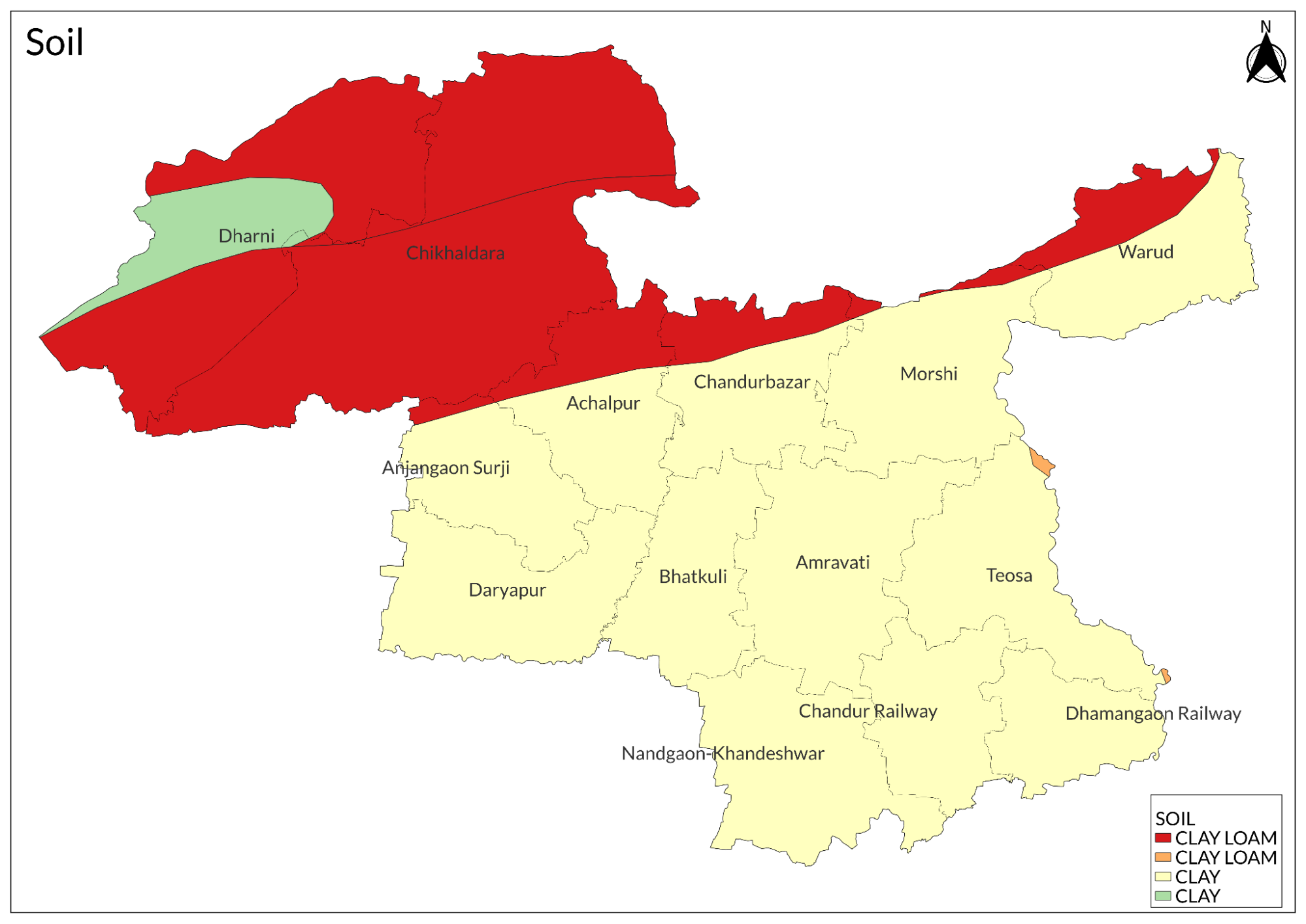

Amravati has a diverse agricultural landscape shaped by its unique soil profiles and climate. The district’s soils range from shallow to deep, with shallow to medium-depth soils typically found in the hilly areas and deeper soils prevailing in the low-lying regions and river valleys. This diverse soil profile contributes to the cultivation of a wide range of crops, making Amravati an important agricultural hub in Maharashtra.

Historically, Amravati’s farmers have cultivated staple crops like tur (pigeon pea) and moong (green gram). These crops have been a cornerstone of the district’s agriculture, and many of them continue to be widely grown today. Alongside these, minor crops such as math (horse gram) and chavali (field beans) were traditionally cultivated, forming an important part of the region’s agricultural history, as noted in the gazetteer. Today, these traditional crops still feature prominently in the district's crop calendar.

According to a report by NABARD (2023-24), the major crops grown in Amravati include soybean, cotton, and tur. Soyabean, the leading crop in terms of area, is grown across 2,69,659 hectares, while cotton is cultivated on 244,002 hectares, and tur occupies 1,06,134 hectares. These crops are primarily sown during the Kharif (monsoon) season, which takes advantage of the district's rainfall patterns. On the other hand, the Rabi (winter) season sees the cultivation of crops such as wheat and gram (chana).

In addition to these core crops, like udad (urad dal) have also become important in recent years, with their cultivation expanding across the district.

Amravati's climate and soil also support the cultivation of a wide variety of fruit crops, particularly in the blocks of Morshi, Warud, Chandur Bazar, and Achalpur. The most famous of these is the Nagpur orange, which dominates the region’s horticultural sector. In fact, according to the NABARD report, the Nagpur orange accounts for over 76% of the horticultural area in the district, as it is well-suited to the local soil and climate conditions. Other notable fruits grown in the district include sweet oranges, bananas, guavas, pomegranates, custard apples, jamuns, and papayas.

Beyond fruits, Amravati also has a strong presence in the cultivation of vegetables and spices. Common vegetables grown in the district include onions, tomatoes, carrots, brinjal (eggplant), and lady's finger (okra). In addition, a variety of condiments and spices such as chilies, ginger, turmeric, garlic, coriander, and fenugreek are farmed, catering both to local consumption and external markets.

Agricultural Communities

Amravati’s agricultural landscape is deeply shaped by its rural communities, for whom farming is not just an economic activity but an intrinsic part of their identity and way of life. The rural population of Amravati, which constitutes a significant portion of the district, relies heavily on agriculture for sustenance and livelihood. According to the NABARD report (2023-24), a large share of this population is engaged in farming activities, with small and marginal holdings making up the bulk of operational land.

The socio-cultural dynamics of farming in Amravati can be traced back to its historical roots. It is noted in the district Gazetteer (1968), that the Marathas and Malis have been the main cultivators in the region, with a long-standing relationship with the land. But the area also has a rich history of agricultural laborers, particularly the Dhangars, Kolis, Korkus, and Mahars, who have traditionally worked as agricultural laborers. Over time, however, these communities’ connection to farming has changed and adapted.

The Korku community, who primarily reside in the Melghat region, have long relied on forest resources for their survival. However, after gaining land rights in 1973, many families transitioned to farming. They practice subsistence farming on small plots, usually no larger than five acres, growing crops like jowar (sorghum), gram (chickpea), and a variety of vegetables.

Despite shifting towards agriculture, many Korku families still rely on forest products, such as tendu patta (tendu leaves), mahua, and bamboo, to supplement their income. As pointed out in the study Socio-economic Status of Tribal Farmers of Melghat Region in Maharashtra (2020), “There is some proportion of the people who own agricultural land, while most of them are agricultural laborers. The wages for agricultural laborers are not promising. Hence, for many families, the source of income and food comes from forest products.” Unfortunately, these forest products are often sold at low prices, due to limited access to markets and poor infrastructure, with many villages being difficult to reach, highlighting that much more attention is needed to address the socio-economic conditions of many of these communities.

Types of Farming

Cotton Cultivation

Amravati, alongside the wider Vidarbha region, has long been synonymous with cotton farming. For centuries, the region’s agricultural landscape has been shaped by this crop. While cotton's roots in Amravati likely stretch back to ancient times, it was during the British colonial period that cotton cultivation transformed into a major agricultural activity, paving the way for the district’s enduring role in the cotton economy.

The significance of cotton in Amravati can be traced back to the colonial era when British interests transformed it into a crucial cash crop. During the 19th century, as the textile industry in Manchester boomed, the East India Company sought a steady and uninterrupted supply of raw cotton. As noted by Meshram and Fulzule in their study, the British were keen on ensuring a steady supply of raw cotton from India, especially after the disruption of cotton supplies during the American Civil War. By the 19th century, the Vidarbha region, including Amravati, became integral to this supply chain, and cotton farming began to expand rapidly.

The British, driven by their economic interests, sought to strengthen their control over the cotton trade. Their primary goal, as noted by the scholars, was to “ensure uninterrupted supply to their textile mills in Manchester and to strengthen their grip on the international cotton trade.” This historical foundation was key to cotton becoming a staple crop.

Today, Amravati remains one of Maharashtra’s major cotton-producing districts, contributing significantly to the state’s overall output. According to government data, Maharashtra produced more than 70 lakh bales of cotton in the 2020-21 crop year, accounting for about a quarter of India's total cotton production. The favorable climatic conditions of the region, adequate rainfall, abundant sunshine, and fertile black soil, as many say, continue to make Amravati an ideal location for cotton farming.

Cultivation Practices and Techniques

The cultivation of cotton begins with sowing, which typically happens in June. Farmers use a seed drill, spacing the rows 18 to 22 inches apart for healthy plant growth. In some areas, a traditional technique known as “chaufuli” is also practiced, where seeds are manually dibbled in a square pattern, a method still favored by some farmers for its perceived benefits.

Cotton farming in Amravati has seen significant growth over the decades. According to the district Gazetteer (1968), between 1950 and 1961, the area under cotton cultivation surged by over 50%, expanding from 2,25,180 hectares to 3,38,340 hectares. This growth, it seems, was largely driven by the increasing profitability of cotton farming and spurred by rising market prices and the introduction of new, high-yielding American cotton varieties.

The Shift in Cotton Varieties: From Traditional to High-Yielding Seeds

A combination of economic factors and agricultural challenges has shaped the transition from traditional Desi cotton seedlings to American varieties in Amravati. This shift, known as crop variety replacement, has redefined cotton farming in the region. While American varieties have boosted productivity, they have also brought new challenges.

The Amravati Gazetteer (1968) documents that the Desi cotton, once dominant in the region, was particularly vulnerable to downy mildew (or dahiya), a disease that could drastically reduce crop quality, often deforming the plants into broom-like structures. With the rising threat of this disease, many farmers saw the need to move away from Deshi varieties, opting for the more resilient American varieties that showed greater resistance to mildew.

Surendra Kumar Singh (2017), Director of the ICAR-National Bureau of Soil Survey and Land Use Planning, reflected on the change, stating, “Things were fine till farmers were cultivating ‘desi’ cotton.” His remark underscores the sense of loss that many feel as traditional varieties, once well-suited to the region's climate and soil, have been gradually replaced by newer, more commercially viable options. The adoption of American cottonseed varieties wasn’t just a response to disease—it was also driven by the potential for higher yields, which was crucial for farmers aiming to meet rising market demands.

The shift was further accelerated by the need for better resistance to various pests and the growing influence of the global cotton market. As noted in the Amravati Gazetteer (1968), “American varieties yield about 150 to 200 lbs. per acre more than their Deshi counterparts,” making them an attractive choice for farmers looking to maximize their earnings. While the transition has provided short-term gains, it has also led to a decline in the cultivation of Desi cotton, pushing farmers toward varieties that may not be as well-suited to the local environment in the long run.

Moving to Genetically Modified Cotton: The Case of Bt Cotton

Although American varieties are less susceptible to this disease, they are vulnerable to other pests like aphids, jassids, and bollworms, which can affect both the quantity and quality of the yield. To address this, some cotton varieties were even imported from Jalgaon, a neighboring district. As challenges with pests persisted, many farmers in Amravati turned to genetically modified Bt cotton, a variety engineered to resist bollworms. This shift marks another significant phase in cotton cultivation in the region, though Bt cotton has sparked considerable debate.

While Bt cotton has shown success in certain areas of Vidarbha, it comes with its own set of issues. Notably, it requires higher moisture content to thrive, which has been problematic in drier regions. However, in Amravati, where favorable soil moisture levels are supported by the Satpura hills and the Purna River, Bt cotton has performed relatively well. Surendra Kumar Singh (2017) pointed out in his interview, “Amravati is one of the few districts in the region where Bt cotton has performed relatively well,” due to the region’s more favorable climatic conditions.

Even so, the long-term sustainability of Bt cotton is still a matter of debate. Environmental concerns about its impact and the growing dependence on seed companies controlling genetically modified seeds continue to stir discussions on the future of cotton farming in Amravati.

Jowar Cultivation

While cotton has taken center stage in Amravati's agricultural landscape in recent decades, jowar (sorghum) continues to be an important crop with deep historical roots in the region. Once the dominant crop, jowar still plays a key role in the region’s agricultural history, providing food for local farmers and valuable fodder (known locally as kadbi) for livestock.

Surendra Kumar Singh, () points out that “It is a misconception that cotton was the region’s traditional crop. Red gram and sorghum (jowar) were the traditional crops. But these got completely wiped out when, due to market forces, cotton was introduced here.” This highlights the enduring importance of jowar, despite the overwhelming rise of cotton.

Historically, jowar has been the most widely grown crop in Amravati, with cultivation spread across all the district's talukas, as noted in the Amravati Gazetteer. Its adaptability to various soil types throughout the region has made it a reliable staple. Typically sown during the kharif season, the crop is planted in July and harvested between December and January.

Jowar is often grown as a rotational crop following cotton cultivation. This system takes advantage of the nutrients and organic matter left behind by the previous cotton crop, reducing the need for additional fertilization. However, when necessary, farmers apply 5–10 cartloads of farmyard manure to support growth. The sowing process involves the use of a tifan (a traditional seed drill), with a seeding rate of approximately 6–8 pounds per acre to ensure optimal plant density.

While cotton may be the crop that grabs the headlines, jowar remains a crucial part of Amravati’s agricultural fabric. Its enduring role not only highlights its importance in the region’s farming systems but also reinforces its place in Amravati's agricultural heritage.

Institutional Infrastructure

In recent decades, the role of modern technology in agriculture has grown steadily, contributing to changes in farming practices across Amravati. According to NABARD’s Potential Linked Credit Plan for 2023-24, the district is equipped with 1,600 agricultural tractors, 255 power tillers, and 673 threshers and cutters. These tools have made certain farming tasks more efficient, reducing manual labor and helping farmers tackle large-scale operations. However, technology adoption in agriculture is not without its challenges, as it often requires substantial investment and technical expertise, factors that can limit its accessibility for some farmers.

Amravati has an average developed agricultural infrastructure, which includes 15 Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs), 301 godowns, 3 cold storages, 4 soil testing centers, 242 farmers clubs, 475 plantation nurseries, and approximately 4000 fertilizer, seed, and pesticide outlets. There are two Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs) supporting agricultural extension services in the region. In addition, there are 28 commercial banks, 1 Regional rural bank and District Central Cooperative bank, 10 Vidharbha Konkan Gramin Bank, 93 branches of Amravati DCCB, and 618 Primary Agricultural. Cooperative Societies. There are seven dams in the district as well, namely Chandrabhaga, Lower and Upper Wardha, Chargad, Malkhed, Purn, and Shahnoor Dams.

Market Structure: APMCs

Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs) are statutory bodies set up by state governments under the Agricultural Produce Market Committee Act. Their main purpose is to regulate the marketing of agricultural produce and ensure that farmers receive fair prices for their crops. APMCs provide a structured marketplace where farmers can sell their produce. In Amravati, almost all talukas have an APMC, and many talukas also feature sub-markets that cater to local agricultural trade.

List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

|

Sr. No |

Name |

Est. Year |

Chairman |

|

1 |

Achalpur |

1955 |

Rajendra Ramrao Gorle |

|

2 |

Dhamangaon Gadi |

1955 |

Rajendra Ramrao Gorle |

|

3 |

Pathrot |

1955 |

Rajendra Ramrao Gorle |

|

4 |

Amravati |

1900 |

Harish Eknathrao More |

|

5 |

Badnera |

1977 |

Harish Eknathrao More |

|

6 |

Anajngaon Surji |

1971 |

JAYANTRAO GUNVANTRAO SABLE |

|

7 |

Chandur Bajar |

1974 |

Rajendra Mahadevrao Yaul |

|

8 |

Chandur Railway |

1974 |

Prabhakarrao Hargovindji Wagh |

|

9 |

Daryapur |

1971 |

Sunil madhanrao Gawande |

|

10 |

Dhamngaon-Railway |

1900 |

kavita shrikant gawande |

|

11 |

Dharni |

1970 |

ROHIT RAJKUMAR PATEL |

|

12 |

Morshi |

1976 |

SACHIN ANILRAO THOKE |

|

13 |

Nandgaon Khandeshwar |

1982 |

PRABHAT PRABHAKARAO DHEPE |

|

14 |

Tiwasa |

1981 |

RAVI SHRIKRUSNA RAUT |

|

15 |

Varud |

1973 |

Narendra Alies Bablu Sheshravji Pawade |

As per the Maharashtra State Agricultural Marketing Board (MSAMB) website, products traded at the regional APMC variety of other significant commodities, including wheat (husked), sorghum (jawar), gram, green gram, pigeon pea, black gram, groundnut pods, potatoes, soybeans, and onions. These products contribute to the district’s agricultural diversity, supporting local markets and farmers' livelihoods.

Farmers Issues

Since 2021, Amravati district has witnessed a troubling rise in farmer suicides, with 370 recorded that year, followed by 349 in 2022, and 323 in 2023. In just the first half of 2024, from January to June, another 170 suicides were reported. The key factors driving this crisis include crop losses, inadequate rainfall, mounting debt, and delays in farm loan disbursements. According to activist Kishore Tiwari, many farmers who shifted to soybean cultivation faced significant setbacks, with yields dropping sharply and prices falling to just ₹4,000 per quintal in 2023.

With limited access to institutional credit, a large number of farmers are forced to rely on small finance firms or moneylenders. This dependency often subjects them to harsh recovery practices, further compounding their financial struggles and deepening the cycle of distress.

Graphs

Irrigation

Cropping Metrics

Land Use and Credit

Sources

2021.Climate Risk and Vulnerability Assessment. India: Maharashtra Agribusiness Network Project (MAGNET). Maharashtra Agribusiness Network Project.https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/link…

Anu V, Abhay Nivasarkar and Sandip Bhowal. Aquifier Mapping and Management of Ground Water Resources: Amravati. Central Ground Water board.https://www.cgwb.gov.in/sites/default/files/…

Cotton Producing States in India. Sathee.prutor.ai.

Govt. Of Maharashtra. 1968. District Gazetteers, Amravati District. Gazetteers Dept. Mumbaihttps://gazetteers.maharashtra.gov.in/cultur…

ICAR. 2017. MAHARASHTRA Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: Amravati. ICAR - CRIDA - NICRA.

K. Tikadar and S. Raj. 2020. Agricultural Extension in Nagpur and Amravati Districts of Maharashtra State. National Institute of Agricultural Extension Management (MANAGE). Hyderabad.https://www.manage.gov.in/publications/discu…

Manka Behl. 2017. In vid cotton can grow well only in Amravati. Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/nag…

Monal Takote, Balakdas Ganvir and Vanita Khobarkar. 2024. Socio-economic status of tribal farmers of Melghat region in Maharashtra. Vol. 7, no. 4. International Journal of Agriculture Extension and Social Development.https://www.extensionjournal.com/article/vie…

NABARD. 2023-24. Potential Linked Credit Plan: Amravati. Maharashtra Regional Office, Pune.

P.M Purkar. 2015. Farmers suicide in Amravati district of Vidarbha: Case Studies. Dr. Panjabrao Deshmukh Krishi Vidyapeeth, Akola.http://krishikosh.egranth.ac.in/handle/1/581…

PTI. 2024. 557 farmers ended lives in 6 months this year in Maha's Amravati: Govt. Business Standard.https://www.business-standard.com/industry/a…

S. Arya & M. Akhef. 2024. 143 in 152 days Amravati is new farm suicide capital of maharashtra. Times of India. Nagpur.http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articlesh…

S. Arya, M. Akhef . 2024. 143 in 152 days Amravati is new farm suicide capital of maha. TOI..https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/nag…

S. M. Joharapurkar, S. S. Thakare, S. N. Ingle. 2024. Economic Assessment of Soybean Production in Amravati District: Costs, Returns, and Farm Size Dynamics. Vol. 42. Issue. 12.https://journalajaees.com/index.php/AJAEES/i…

S. Meshram and A. D. Fulzele. 2020. Cotton Cultivation and trade in Vidharbha up to 1947. Vol. 11, no. 2. Vidyabharati International Interdisciplinary Research Journal.]https://www.viirj.org/vol11issue2/22.pdf

S. N. Suryawanshi, S. A. Gawande , N. Nandeshwar, V. J. Rathod, M. Gaikwad and V Bane. Diversification of Major Crops in Amravati District. 2017. Vol. 35, no. 4. International Journal of Tropical Agriculture.https://serialsjournals.com/abstract/83439_2…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.