Contents

- Crop Cultivation

- Agricultural Communities

- Festivals & Rituals Related to Farming

- Dhawara

- Yel Amavasya Puja

- Types of Farming

- Jowar Farming

- Use of Technology

- Institutional Infrastructure

- Market Structure: APMCs

- List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

- Farmers Issues

- Environmental Challenges and Vulnerability

- Migration: A Consequence of Unpredictable Weather

- Economic Fallout: Debt, Suicide, and Instability

- Graphs

- Irrigation

- A. No. of Projects

- B. No. of Ponds/Vilage Lakes and Storage Dams

- C. Irrigation Beneficiary Area vs Irrigated Area

- D. Share of Beneficiary Area Irrigated

- E. Tubewells and Pumps Installed In The Year

- F. Irrigation and Water Pumping Facilities

- Cropping Metrics

- A. Share in Total Holdings

- B. Cultivated Area (With Components)

- C. Gross Cropped Area (Irrigated + Unirrigated)

- D. Share of Cropped Area Irrigated

- E. Distribution of Chemical Fertilizers

- Land Use and Credit

- A. Area of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- B. Size Groups' Share in Total Agricultural Land Holdings Area

- C. No. of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- D. Size Groups' Share in Total No. of Agricultural Land Holdings

- E. Agricultural Lending

- F. Agricultural Credit as a share of Total Credit

- Sources

BEED

Agriculture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

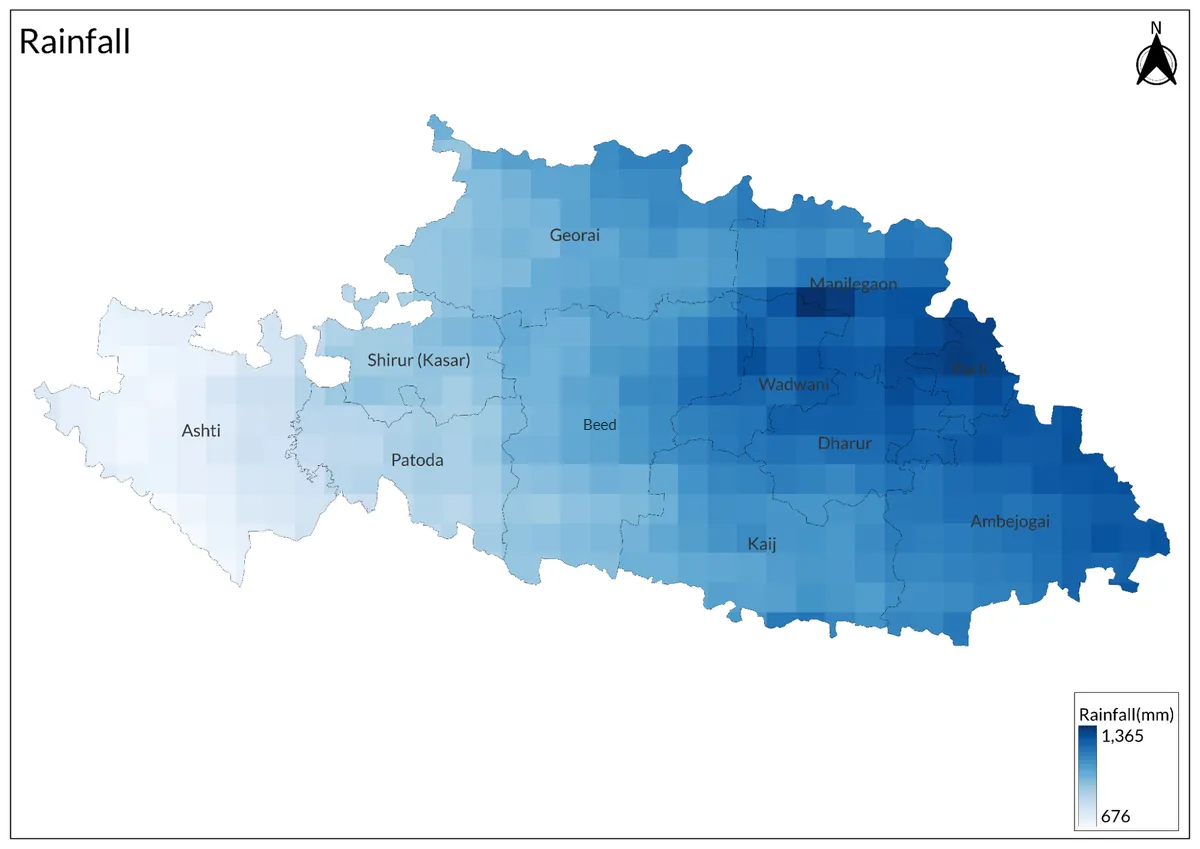

The Beed district is an agricultural region that is distinguished by its varied climate and terrain. According to the KVK website, the district covers a geographical area of 1,068,600 hectares, with 81.97% of it being cultivable land. The district lies mainly in the Godavari Basin, with the Godavari River, the Sindphana River in the north, and the Manjra River in the south draining the region. While the southern part of Beed benefits from ample rainfall, supporting a variety of crops, the northern part is dry and faces significant challenges for farming.

Agriculture continues to be the primary source of livelihood for many in Beed; however, the district is grappling with a serious crisis of farmer suicides, with Beed, according to news reports, recording the highest number of such deaths in Maharashtra in 2024. Furthermore, the district is classified as drought-prone, a factor that significantly aggravates the challenges faced by farmers.

Crop Cultivation

The district has long been known for cultivating staple crops such as Jowar (sorghum), Bajra (pearl millet), and Wheat. Groundnut (peanut) is another key non-food crop grown extensively in the region, along with notable Kharif (monsoon-cropping season) crops including Maize, Tur (pigeon pea), Udid (black gram), Chillies, and Bhendi (okra).

The agricultural landscape here is shaped by seasons, as outlined in a recent NABARD report (2023-24). During the Kharif (monsoon) season, crops such as Cotton, Soybean, Bajra (pearl millet), and various Pulses are grown, supported by the rainfall from the Southwest Monsoon. In the Rabi (winter) season, crops like Chickpea, Jowar (sorghum), Wheat, and maize (corn) are cultivated, with the lighter rainfall from the Northeast Monsoon aiding their growth.

The climate of Beed is considered suitable for horticulture, with crops such as Mango, Lemon, Pomegranate, Custard Apple, and Sweet Lime commonly grown in the region. Notably, among these fruits, Beed’s Custard Apple has earned a Geographical Indication (GI) tag from the Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority (APEDA), underscoring its unique regional significance.

Agricultural Communities

Farming in Beed sustains the vast majority of its rural population and forms the backbone of the district's economy. At the time of the 2011 Census, it was recorded that Beed had a population of 25.85 lakh, with around 80% (20.71 lakh) of them living in rural areas. Small-scale farming appears to have formed the core of the district’s agrarian structure, with most cultivators managing modest landholdings, for, as per the NABARD report (2023-24), 83.04% of landholders in Beed own less than 2 hectares of land.

The district is home to a variety of communities, each of which has deep historical ties to farming. Key agricultural communities in the district include the Kunbis, Mahars, and Mangs, all of whom have traditionally played significant roles in sustaining the area’s farming economy.

Festivals & Rituals Related to Farming

Dhawara

According to Shahu Patole (2024), Dhawara is a cherished tradition in the local farming culture, marking the celebration of a successful harvest with a sacred meal. The preparations for Dhawara begin on the new moon of Diwali, a day dedicated to worshipping the Pandavas, the five legendary brothers from the Mahabharat. In the fields, five small stones are selected and painted with Chuna (limewash), symbolizing the Pandavas.

As part of the ritual, wheat flour dough is shaped into various forms, such as plain balls, fruits, and lamps, before being steamed. These, along with dried dates, dry coconut, Ambil (a tangy buttermilk preparation infused with chillies and coriander), Kadhi (a tempered chickpea-buttermilk curry), and Wadya (steamed gram flour cakes), are offered as Naivedya (a devotional offering). A Morva (medium-sized earthen pot) and Shendur (a sacred red powder) are also placed near the symbolic Pandavas.

In keeping with tradition, five stacks of Jowar Pachundas (bundles of harvested sorghum) are arranged upright before the stones. A lamp is then placed inside the Morva and lit as a mark of reverence. At dusk, the Morva is carefully buried near the painted stones, symbolizing the completion of the Dhawara ritual and expressing gratitude for the harvest.

Yel Amavasya Puja

A puja similar to Dhawara is performed during Yel Amavasya (the new moon night that falls in January). The Yel Amavasya puja is still a common and notable festival related to farming in the Ashmak region, which comprises areas of present-day Maharashtra and Karnataka.

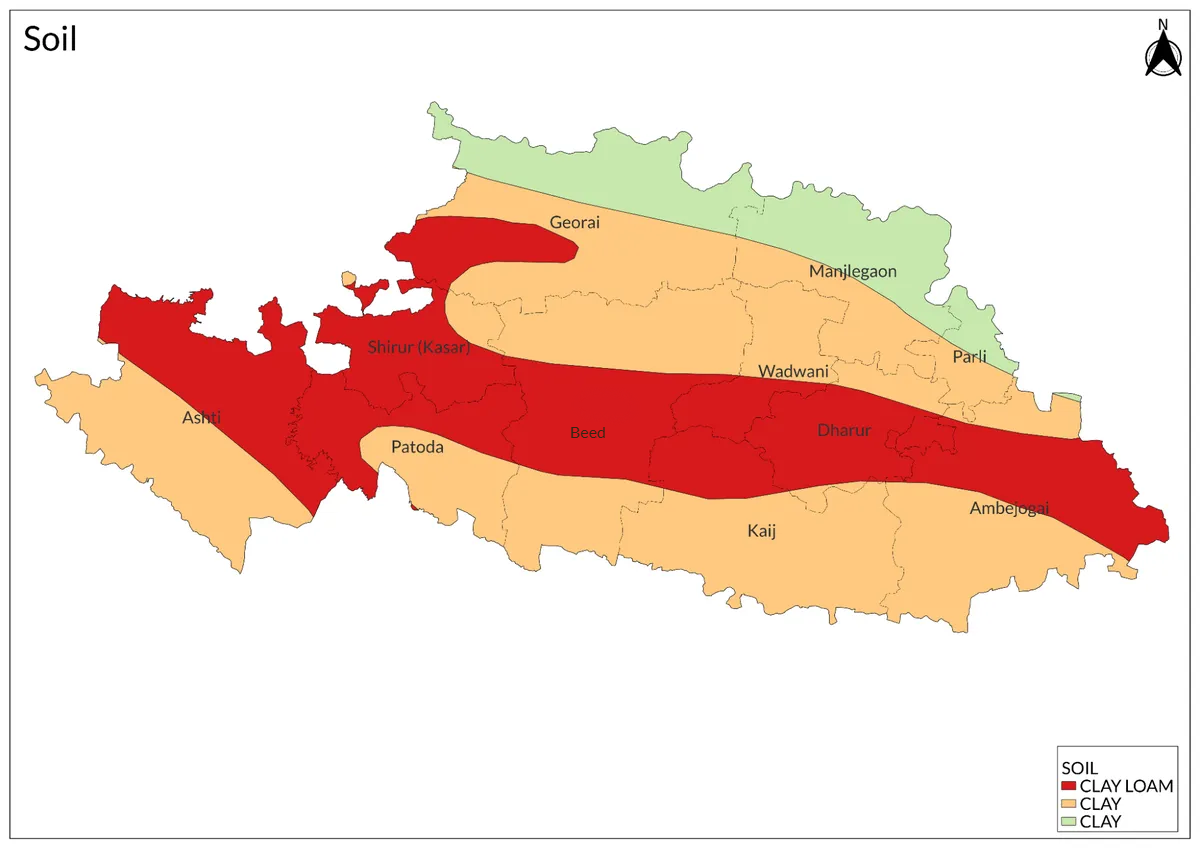

Types of Farming

Agriculture in Beed is shaped by the region's soil types, topography, and climate. As with any other region, these factors play a vital role in determining the crops that thrive in the area. The KVK profile of the district highlights that the soil in Beed is categorized into light, medium, and heavy types, each supporting distinct farming practices.

Beed is known for cultivating a wide range of crops, especially during the Kharif (monsoon) season. Crops such as cotton, sorghum (jowar), soybean, red gram, sugarcane, and pearl millet dominate the landscape. Light soils, in particular, are ideal for the cultivation of crops like bajra (pearl millet), red gram, and sorghum, which require specific soil and climatic conditions to flourish.

Jowar Farming

Over the years, Beed’s agricultural landscape has been increasingly shaped by the rise of crops like cotton and soybeans. However, one crop that has remained a consistent fixture in the region’s farming heritage is Jowar (Sorghum). Even the district Gazetteer (1969) describes it to be the district’s “staple food crop.” According to the NABARD report (2023-24), Jowar currently occupies 13.23% of the total farming area in Beed, ranking behind crops like soybean and cotton in acreage. Jowar is grown across various regions of the district, with Kharif Jowar dominating in areas like Ambejogai, Kaij, and parts of Beed talukas, while Rabi Jowar is cultivated in other parts.

In the past, Jowar occupied a much larger share of Beed’s cultivated land. It is recorded in the district Gazetteer (1969) that in 1961–62, it was grown on 3,45,237 hectares (8,52,438 acres) out of the 6,51,183 hectares under food crops.

Cultivation of Jowar typically begins with ploughing during the hot season, followed by the first harrowing in late May. After the onset of the monsoon, two more harrowings prepare the soil. When plants reach 6 to 8 inches in height, hand weeding and bullock-drawn interculturing are commonly done. Traditionally, farmers used a three-coulter seed drill with 9–10 inch spacing. A few decades ago, the Poona method—planting seeds 18 inches apart—was introduced. According to the Gazetteer (1969), this increased yields by 25–40% under dry conditions.

In terms of varieties, while local strains such as Piwali (Kharif) and Dagadi (Rabi) were traditionally grown, as noted in the gazetteer, there has been a shift towards improved varieties like PJ 4 K and PJ 16 K (for Kharif) and PJ 4R and M 35-1 (Maldandi) (for Rabi). Alongside Jowar, farmers also usually grow pulses, oilseeds, and occasionally fibre crops, supporting a diversified cropping system.

Use of Technology

For as long as farming has existed, specific tools have been integral to optimizing agricultural processes. In Beed, traditional agricultural implements remain a core part of farming practices, with many farmers continuing to rely on these age-old tools rather than modern machinery. Common hand tools include the axe (Kurhad), used for cutting wood, as well as the pharshi, pick-axe, spade, masker, and weeding hook, each serving distinct functions in soil preparation, planting, and crop maintenance. Despite the availability of more advanced farming technologies, these traditional implements continue to be preferred by many due to their accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and suitability to the region's farming needs.

Institutional Infrastructure

According to the NABARD’s Potential Linked Credit Plan (2023-24) report, Beed has an underdeveloped agricultural infrastructure, including 10 Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs), 64 godowns, 1 cold storage facility, 7 soil testing centers, 3 plantation nurseries, 233 farmers' clubs, and approximately 6,800 fertilizer, seed, and pesticide outlets. Additionally, there are two Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs) supporting agricultural extension services in the region.

Since the district also lies in the drought-prone Marathwada region, a special focus has been placed on rainwater harvesting and increasing the level of groundwater through the creation of water catchment ponds and small bandhs (dams). Some of these were made by the state government under its “Jalyukt Shivir Yojna,” while others were built by various NGOs such as the Paani Foundation.

Market Structure: APMCs

Beed district consists of 11 talukas: Beed, Georai, Patoda, Ashti, Shirur (Kasar), Ambajogai, Kaij, Majalgaon, Dharur, Parli (Vaijnath), and Wadwani. According to the Maharashtra State Agricultural Marketing Board (MSAMB) website, there are 10 Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs) spread across the district. These APMCs are longstanding, with some dating back to the 1940s and 1950s, reflecting an early attempt to build agricultural infrastructure, or rather a structured marketplace in the district.

List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

|

Sr. No |

Name |

Est. Year |

Chairman |

Submarkets |

|

1 |

Parli Vaijnath |

1940 |

Panditrao Pandurangrao Munde |

|

|

2 |

Beed |

1949 |

Sarla Kamraj Mule |

2 |

|

3 |

Ambejogai |

1955 |

Madhukar Balasaheb Karchgunde |

|

|

4 |

Majalgaon |

1954 |

Jaydatta Subhashrao Narwade |

|

|

5 |

Gevrai |

1959 |

Mujib Nashib Pathan |

|

|

6 |

Kille Dharur |

1960 |

Mangesh Mahadev Tonde |

4 |

|

7 |

Kada

|

1972 |

Ramjan Noormohmad Tamboli |

|

|

8 |

Patoda |

1984 |

Rupali Kiran Shinde |

2 |

|

9 |

Kaij |

1998 |

Anukshrao Sambhurao Ingle |

1 |

|

10 |

Vadvani |

2009 |

Sambhaji Murlidhar Shinde |

|

The key commodities traded in these markets include cotton, wheat (husked), sorghum (jawar), gram, pigeon pea, and soybean.

Farmers Issues

Environmental Challenges and Vulnerability

Beed has faced persistent challenges of erratic rainfall and water scarcity for many years. Beed has been classified as a drought-prone district, Beed, along with Hingoli and Parbhani and experiences drought conditions every 10 years, according to the India Meteorological Department (2005). This makes the region highly vulnerable to water shortages, which directly affect its agricultural economy.

According to the IMD’s climate report on Maharashtra, much of Beed is classified as semi-arid, with several areas falling under a dry climate category. This underscores the challenges farmers face, as the majority of agricultural activity in the district is rain-fed and therefore vulnerable to erratic rainfall patterns.

Economist H.M. Desarda (2024) notes that while total annual rainfall has remained relatively stable, its intra-seasonal distribution has become increasingly erratic. Longer dry spells are now punctuated by sudden, intense downpours. These changes not only damage crops but also wash away topsoil, which affects agricultural productivity.

Migration: A Consequence of Unpredictable Weather

Journalist Varsha Torgalkar (2024), writing for IndiaSpend, highlights the lived experiences of farmers in Beed, which have been affected by these unpredictable weather patterns. Erratic rainfall has disrupted agricultural cycles and rendered livelihoods increasingly precarious, compelling many farmworkers to migrate for seasonal labor. With limited non-agricultural employment opportunities in the region, migration has become a necessary coping mechanism.

These climate-induced disruptions make it difficult for farmers to plan sowing and harvesting, compounding their exposure to economic shocks. The absence of support systems further intensifies their vulnerability.

Economic Fallout: Debt, Suicide, and Instability

The economic impact of this volatility is far-reaching. With failed harvests, farmers have little to fall back on and are often forced into a cycle of debt. This financial strain, coupled with the constant uncertainty, has contributed to a disturbing rise in farmer suicides. According to a 2023 Deccan Herald report, 685 farmer suicides were recorded in Marathwada that year, with 294 deaths occurring during the monsoon season. Beed alone accounted for 186 of these cases. Data from the District Commissioner’s Office shows that Beed consistently ranks among the highest in farmer suicide rates, with sharp increases during drought years. This ongoing crisis in Beed and the larger Marathwada region points to a growing need for targeted interventions.

Graphs

Irrigation

Cropping Metrics

Land Use and Credit

Sources

685 farmer suicides in Marathwada so far in 2023, Deccan Heraldhttps://www.deccanherald.com/india/maharasht…

APEDA. gov.inhttps://apeda.gov.in/apedawebsite/about_aped…

Beed.gov.in.https://drikvkbeed.org/district-profile/

Gazetteers Department. 1969. Beed District. Government of Maharashtra.

India Meteorological Department. 2005. "Climate of Maharashtra." IMD Pune.https://imdpune.gov.in/library/public/Climat…

NABARD. 2023-24. Potential Linked Credit Plan: Ahmednagar. Maharashtra Regional Office, Pune.

Patole, Shahu. 2024. Dalit Kitchens of Marathwada.Translated by Bhushan Kargaonkar. Harper Collins: New Delhi.

PTI. 2024. "Marathwada: 430 Farmer Suicides This Year; Highest In Agriculture Minister Dhananjay Munde's Beed. Free Press Journal.https://www.freepressjournal.in/pune/marathw…

Varsha Torgalkar. 2024. "Why Marathwada's Farm Workers Are Migrating Even In Summer." IndiaSpend.https://www.indiaspend.com/agriculture/why-m…

Venkateswarlu, B., Ahire, R., & Kapse, P. (2019). Farmers suicides in Marathwada Region of India: a causative analysis. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences, 8(04), 296–308.https://www.ijcmas.com/8-4-2019/B.%20Venkate…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.