Contents

- Physical Features

- Climate

- Geology

- Soil

- Rivers

- Botany

- Wild Animals

- Birds

- Forest Reserves

- AnerDam Wildlife Sanctuary

- Land Use

- Environmental Concerns

- Land Degradation

- Air Pollution

- Climate Change Vulnerability

- Water Scarcity

- Conservation Efforts

- Community restores grasslands

- Malachipada Protests

- Graphs

- Water

- A. Rainfall (Yearly)

- B. Rainfall (Monthly)

- C. No. of Rainy Days in the Year (Taluka-wise)

- D. Evapotranspiration Potential vs Actual Numbers (Yearly)

- E. Annual Runoff

- F. Runoff (Monthly)

- G. Water Deficit (Yearly)

- H. Water Deficit (Monthly)

- I. Soil Moisture (Yearly)

- J. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Bore Wells

- K. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Dug Wells

- Climate & Atmosphere

- A. Maximum Temperature (Yearly)

- B. Maximum Temperature (Monthly)

- C. Minimum Temperature (Yearly)

- D. Minimum Temperature (Monthly)

- E. Wind Speed (Yearly)

- F. Wind Speed (Monthly)

- G. Relative Humidity

- Forests & Ecology

- A. Forest Area

- B. Forest Area (Filter by Density)

- C. Wildlife Projects (Area and Expenses)

- Human Footprint

- A. Nighttime Lights

- Sources

DHULE

Environment

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Dhule district, located in northern Maharashtra, is characterized by its diverse landscapes, ranging from the rugged Satpuda hills to the fertile plains along the Tapi River. Despite its natural richness, the region faces significant environmental challenges, including deforestation, soil degradation, and seasonal water scarcity. These issues, coupled with a semi-arid climate and complex geological formations, shape the district’s ecological balance and influence its agricultural and developmental prospects.

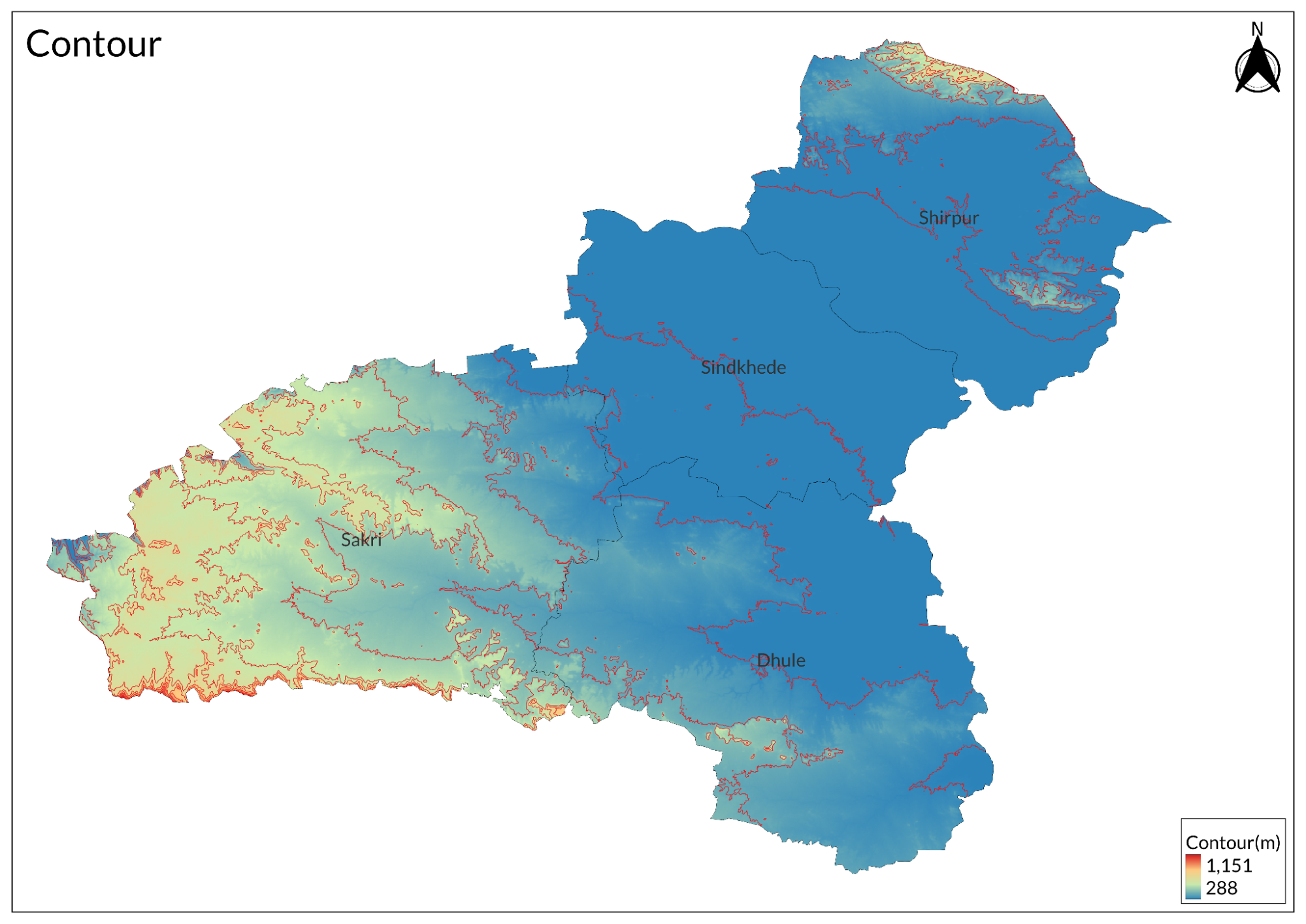

Physical Features

The district has four main natural regions. The Satpuda Region features the Satpura Range, a key part of central India. The Tapi Valley Proper includes fertile land along the Tapi River, rich in wildlife. The Region of Dykes and Residual Hills of the Sahyadri Spur has hills and dykes with eastward streams in the southern Nandurbar taluka. Lastly, the Navapur and Western Nandurbar Region, located below the Sahyadri hills, faces west and has steep, forest-covered hills.

Climate

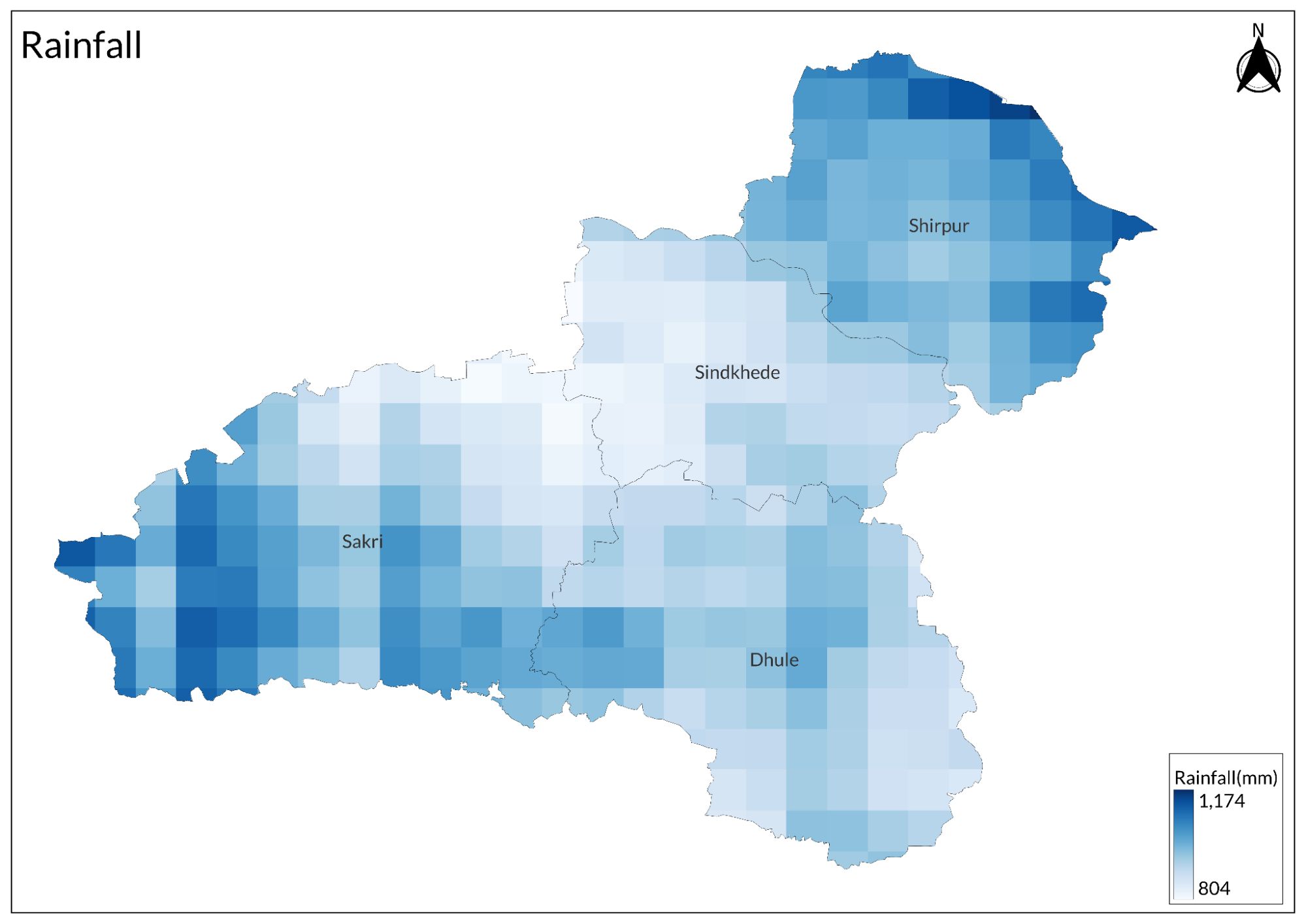

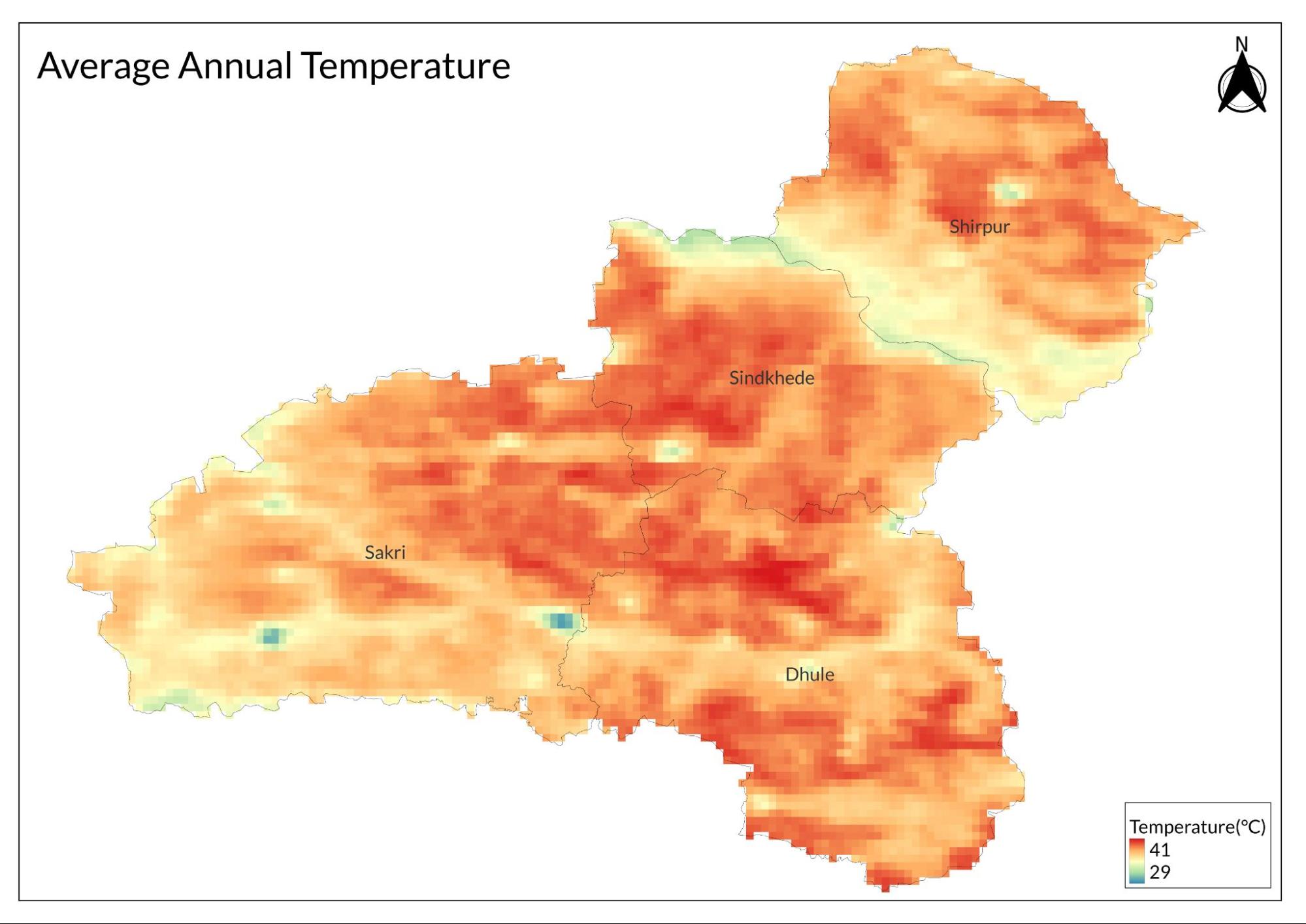

The year is divided into four seasons: a cold season from December to February, a hot season from March to May, the southwest monsoon from June to September, and a post-monsoon period in October and November. Rainfall is heaviest in the hilly regions of the Western Ghats and Satpuda ranges, with July typically being the rainiest month, contributing to about 42 rainy days annually. Temperature-wise, data from the meteorological observatory in Nandurbar shows a steady rise from late February to May, which is the hottest month characterized by hot, dry winds. The arrival of the southwest monsoon in mid-June brings cooler temperatures and pleasant weather until early October, when temperatures start to rise again.

By November, both day and night temperatures drop significantly, with January being the coldest month. Cold waves associated with western disturbances can lead to chilly nights, resulting in a wide range of temperatures throughout the year. The hottest month is typically May, with average maximum temperatures reaching around 40.7°C (105.3°F), while January is usually the coldest month, with average minimum temperatures around 12°C (54°F).

Geology

The geological formations found in the Dhule district include:

|

Name of the Formation |

Age |

|

Alluvium |

Recent |

|

Deccan Basalt |

Eocene |

|

Bagh Beds |

Upper Cretaceous |

The oldest geological formation in the northwestern portion of the district is the Bagh Beds, which date to the Upper Cretaceous period. These beds are prominently exposed along the banks of the Devaganga River and its tributaries, where sections of considerable thickness can be observed. The hills to the east of the river, particularly towards Attior Arithi, are primarily composed of sandstone, with shale beds visible near the summits. Here, the thickness exceeds 300 meters, and the beds exhibit a quaquaversal dip, sloping away in all directions. The sandstones are well-hardened and frequently intersected by dykes and large irregular intrusions of trap rock.

To the east of Devaganga, near Surpan, a small area is occupied by Cretaceous beds, with the summit of the high range known as 'Bawagupnyo' being composed of trap rock. Near Warwee (or Vami), shale interspersed with limestone and oyster beds can be found. In the calcareous shale located just below the trap on the western spur of Bawagupnyo Hill, shark's teeth are abundant within black calcareous rock that contains irregular siliceous masses.

To the west, Cretaceous rocks lie beneath the traps, while both the northern and southern boundaries are faulted. The eastern boundary exhibits an abruptly denuded termination, suggesting that lower lava flows were consolidated against a preexisting sandstone cliff. This is particularly evident north of Babasiraj Hill, where trap rock suddenly overlaps. From the summit of Babasiraj hill, one can infer a general anticlinal structure of the rocks with an east-west axis, with trap formations on the hills dipping to both the north and south. East of Babasiraj hill, the rocks dip to the south and southeast, which accounts for the absence of Cretaceous rocks in Akrani. Notably, there is a slight but distinct unconformity between the overlying traps and the Bagh Beds.

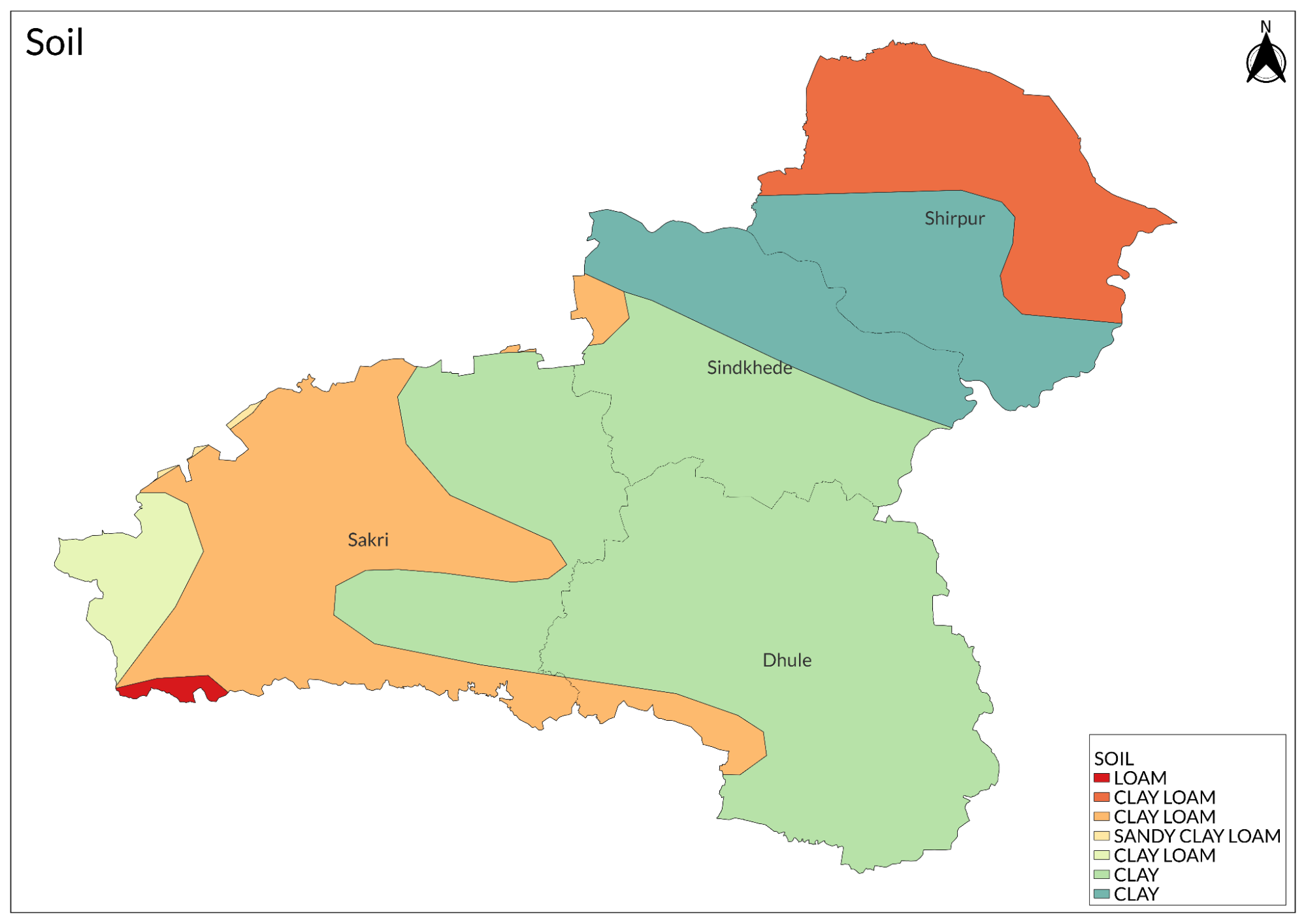

Soil

The Tapi valley has rich, deep black soil that is highly fertile, with some exceptions. Near the main river and its tributaries, erosion has severely damaged the land, stripping away the topsoil.

The soil quality gradually changes as you move away from the river, heading north toward the Satpudas or south toward the hills and dykes. The fertile soil transitions into coarser, shallower, and stonier soil.

Rivers

The Narmada River forms the district's western and northern border for about 70 km. Its course notably mirrors the changing strike of the northern Satpuda high range. Due to the steep rise of its banks through the Satpuda slopes, the river offers limited value to the district.

Several tributary streams flow into the Narmada within the district, draining the northern Satpuda slopes through steep, narrow, winding valleys. These streams, fed by springs on the northern slopes of the main ranges, have plentiful water. However, the extremely rugged terrain makes it difficult to fully utilize this water for agricultural development. The main tributaries of the Narmada, from east to west, are the Jharkal, Udai, Khai, Sambar, and Devganga. Two recurring trend lines appear in the streams' flow direction: one parallel and another nearly perpendicular to the Narmada's direction. These trends become increasingly pronounced from west to east, becoming particularly distinct east of the Jharkal beyond the district's boundaries.

The Jharkal, originating outside the district, flows along its boundary in a deeply trenched valley before joining the Narmada. It receives drainage from streams running down the Toranmal plateau on its left bank. The Udai River begins near Valamba village in the springs just north of the southern Satpuda high range. It flows eastward for about 35 km between this range and the one north of it, then makes a sharp turn northward, following its Chandseli tributary stream's trend. After passing Dhadgaon, it follows a winding course generally northeast before joining the Narmada.

The Devnand (also known as Khai) starts very close to the Udai's source, north of Valamba village. It follows a similar but shorter easterly course beyond another Satpuda range, then turns north and northeast. After merging with the Katri, which flows by Kathi, it continues northeast as the Khai until it meets the Narmada. The Sambar, a shorter river, flows generally westward to join the Narmada. The Devganga, the district's westernmost Narmada tributary, originates on the Rahuvala Dongar's southern slopes. It initially flows south until joining the Dahel river, then flows west and forms the district boundary with a northwestern course before meeting the Narmada. Its tributary, the Dahel, begins near Valamba village and flows northwest until joining the Devganga. Notably, three streams: the Udai, Devnand, and Dahel, all originate on the slopes of a 1,000-meter peak west of Valamba village, and despite following different paths, they all eventually flow into the Narmada.

Botany

The forests of Dhule have many different types of trees and plants. Most of these plants lose their leaves in the dry season. The amount of rain (between 889 to 1270 mm) and the soil type determine what grows where. Teak is the most common and important tree, growing best in areas like Taloda and Devmogra. Other important trees include ain, dhavda, shisam, and khair. The Satpuda hills show interesting changes in plant types every 30-45 km. The eastern parts have mostly anjan and salai trees, while the Shahada area has mainly khair trees. The district also has several types of grasses, including rosha grass, which is used to make medicines and perfumes. Along the roads, one can commonly find neem, tamarind, and babhul trees. The moha tree is especially important for the locals as its flowers are used to make alcohol and are a vital food source for tribal communities during the hot months.

Wild Animals

In the past, Dhule's forests were home to many wild animals, including elephants, until the 17th century. Tigers were once so numerous that in 1822, they killed 500 people and 20,000 cattle, leading to special hunting efforts. Today, while tigers are no longer found in the plains, they still live in the Satpuda hills and other forested areas, though their numbers have greatly decreased. Panthers come in three types: two large varieties and a smaller one known as the "dog-slayer." The district also has hyenas, wolves, jackals, foxes, and wild dogs that hunt in packs in the Satpuda hills. Black bears can be found in forest-covered hills, and they particularly enjoy eating Moha flowers, which seem to make them drunk and more likely to attack humans. Wild pigs, though fewer now, are considered the most troublesome for farmers as they destroy crops like sugarcane, sweet potatoes, and millets. Other animals include bison in the Satpuda hills, deer (including sambar, spotted deer, and barking deer), blue bulls, antelopes, and hares.

Birds

Game birds include peafowl, which live in woods and shady gardens, grey jungle fowl, and spur fowl found in forests. The district has two types of partridges: the grey partridge found everywhere, and the less common painted partridge. Several kinds of quail live in the area, including bush quails, common grey quail, and rain quail. In water bodies, you can find ducks, including the Brahmani duck, whistling teal, and common teal. Among the birds of prey, there are different types of vultures, eagles, kites, and owls. Other common birds include kingfishers (especially near water bodies), parrots (like the rose-ringed parakeet), woodpeckers (including the striking golden-backed woodpecker), crows, bulbuls, and various kinds of pigeons and doves. Many of these birds can still be found in the district today, especially in forested areas, though their numbers have changed over time.

Forest Reserves

AnerDam Wildlife Sanctuary

The AnerDam Wildlife Sanctuary, situated in the Shirpur taluka of Dhule district, spans across the southwestern side of the Satpura hill ranges around the Aner river's catchment area. The sanctuary shares borders with Yawal Wildlife Sanctuary in Jalgaon district and forest areas of Khargone district in Madhya Pradesh. Located 71 km from Jalgaon railway station, the sanctuary can be accessed through regular buses from Shirpur and Lasur Road Bus Stand. The area features a Southern moist deciduous forest with degraded scrubland and patches of wooded land. Common trees include Khair, Hiwar, Babul, Bel, and various species of Albizzia, while shrubs like Vites negundo and Carissa carandas are abundant. The sanctuary is home to diverse wildlife, including leopards, wild cats, black bucks, jackals, wolves, and various birds such as peacocks, cranes, storks, and Brahmani ducks. While the Aner Dam is a major tourist attraction, the sanctuary faces several challenges, including illicit cutting, forest fires, encroachment, hunting, and the invasive spread of Lantana camara weed, damaging grasslands. The sanctuary, managed as part of the Aurangabad Wildlife Division and overseen by the Range Forest Officer at Shirpur, remains largely inaccessible during the rainy season, though visitors can stay at the PWD rest house in Shirpur or forest rest houses at Rohini and Chopda.

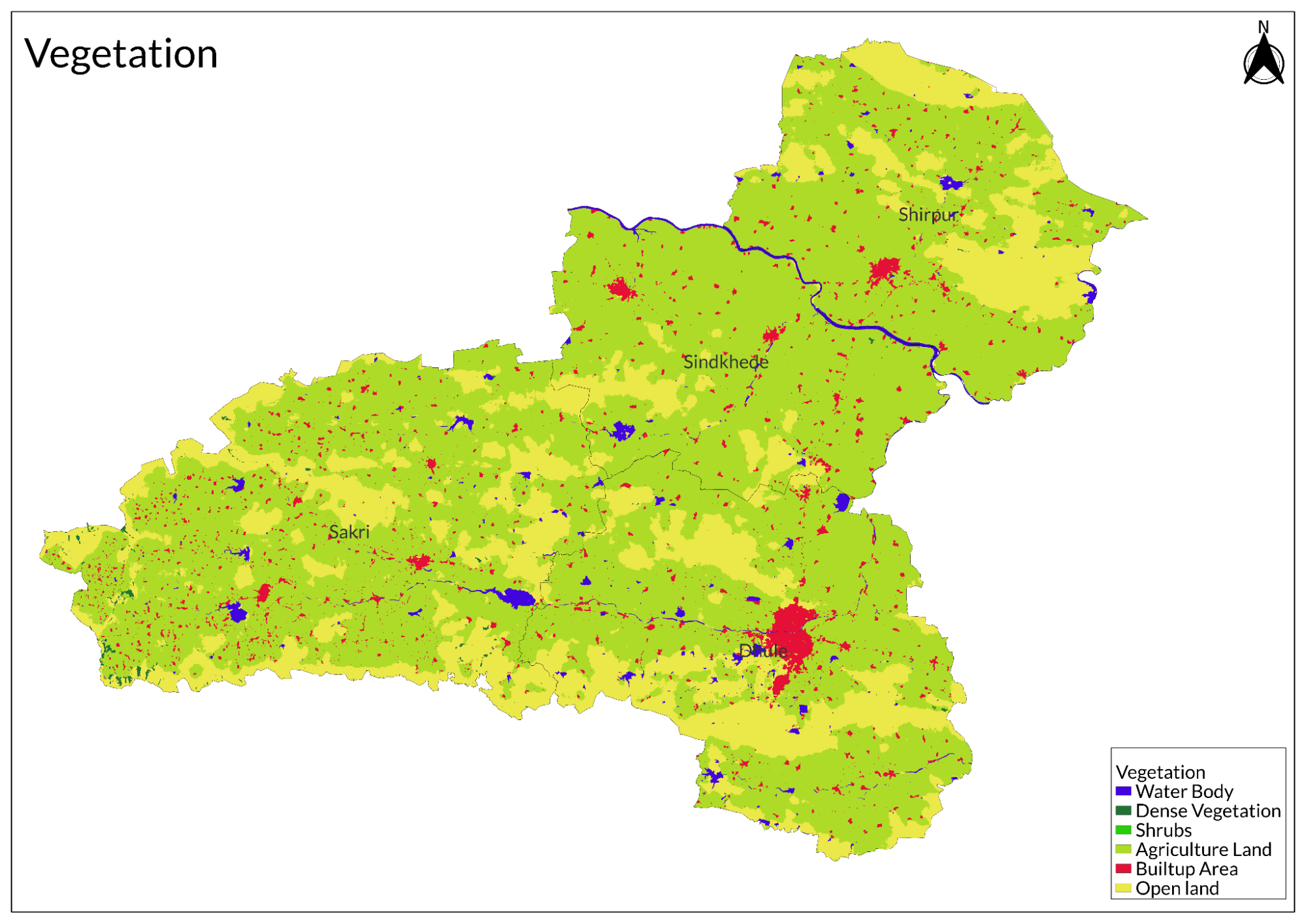

Land Use

Environmental Concerns

Land Degradation

Soil degradation in Dhule district, Maharashtra, poses a severe challenge to agricultural productivity, with farmers like Hemant Waman Chowre struggling against topsoil erosion during monsoon rains. The region's shallow soil, only about six inches deep, combined with gentle slopes, leads to frequent crop losses as even light rainfall washes away young plants. This issue is widespread, with neighboring farmers reporting similar problems, including deep holes forming in their fields after storms. The Indian Space Research Organisation’s Desertification and Land Degradation Atlas ranks Dhule as one of India’s most affected districts, with 64.2% of its land suffering from desertification or degradation. The Deccan Trap’s underlying geology, composed of igneous rock and poor soil permeability, further limits agriculture to a single rainfed crop per year, while 26% of the district is classified as scrub vegetation, of which 94% is severely degraded.

Water erosion, affecting 23.75% of Dhule’s land, is the primary driver of soil loss, occurring predominantly as sheet erosion that gradually strips away the topsoil. Sparse vegetation further exacerbates this issue, leaving the land vulnerable to erosion during heavy rains. Forest cover is minimal, at just 4.2% of the district’s area, and is further threatened by overgrazing, illegal logging, and intentional fires set by local grazers, preventing natural regeneration. These biotic pressures, combined with the district’s fragile soil conditions, contribute to the ongoing cycle of land degradation, severely impacting the region’s agricultural sustainability.

Air Pollution

Dhule district in Maharashtra faces significant air pollution challenges, primarily due to elevated levels of PM2.5, which frequently lead to "moderate" to "poor" air quality, especially during festive periods like Diwali when fireworks usage spikes. The pollution stems from multiple sources, including vehicle emissions from heavy traffic and older vehicles, dust from unpaved roads, and agricultural practices like crop residue burning in surrounding areas. While industrial activities are not as prominent as in larger cities, small-scale industries also contribute to air quality degradation. Recent data indicate that PM2.5 levels in Dhule often exceed safe thresholds, posing serious health risks, particularly for individuals with respiratory conditions, and causing widespread breathing discomfort among residents.

Climate Change Vulnerability

Dhule district in Maharashtra is increasingly vulnerable to climate change, with erratic monsoons, rising temperatures, and water scarcity severely impacting agriculture, livelihoods, and natural resources. The region receives an average annual rainfall of about 512 mm, often insufficient for farming, leading to frequent crop failures, while higher temperatures accelerate soil degradation and increase pest infestations, further threatening yields. Farmers struggle with fluctuating production, making long-term planning difficult. Additionally, limited awareness of climate change exacerbates these challenges, highlighting the need for targeted adaptation strategies. Recent studies categorize Dhule as moderately vulnerable to extreme weather events, placing it alongside 14 other districts in Maharashtra facing similar risks.

Water Scarcity

Dhule district in Maharashtra faces severe water scarcity due to uneven rainfall distribution, declining groundwater levels, and high agricultural water demand. Despite receiving an average annual rainfall of 660 mm, inconsistent timing and distribution create significant challenges, often leading to moderate drought conditions. Excessive groundwater extraction for agriculture has caused alarming declines, particularly in the southern and southeastern regions, with seasonal fluctuations worsening the situation. Many villages rely on water tankers for basic needs, exacerbated by inefficient irrigation and poor conservation practices. Sindhkheda Taluka is among the most water-stressed areas, struggling with critically shallow groundwater levels.

Conservation Efforts

Community restores grasslands

Lamkani, a village 40 km from Dhule, Maharashtra, has undergone a remarkable transformation through community-led efforts to restore its grasslands and enhance drought resilience. Once known for its abundant fodder, the village faced severe ecological degradation following droughts in the 1970s and 1990s, leading to barren landscapes, water scarcity, and migration. The revival began in 2000 when Dhananjay Newadkar, a local pathologist, launched a watershed development program to restore the 600-hectare ridge that fed Lamkani’s streams. He introduced bans on grazing (charai bandhi) and tree felling (kurhad bandhi) to protect the fragile ecosystem, though enforcement was initially challenging due to the village’s pastoralist Dhangar community.

Through a phased approach, Newadkar gradually protected 50 hectares of grassland each year, encouraged rotational grazing, and used folk artists to spread awareness about conservation. These efforts led to significant improvements in water availability, with the village transitioning from tanker dependence to self-sufficiency, even in droughts. The water table rose, and previously degraded lands began flourishing with nutritious grasses like pavna and dongari, benefiting both livestock and biodiversity. As irrigation became more reliable, farmers diversified crops, growing onions, cotton, wheat, bajri, jowar, and fruits, supported by government schemes and NGOs like Watershed Organisation Trust (WOTR).

Despite its success, Lamkani still faces challenges, including the risk of grassland fires, which the community combats with fire lines and WhatsApp-based rapid response teams. The COVID-19 pandemic also made enforcing grazing bans difficult, leading to some unauthorized grazing. Nevertheless, Lamkani’s restoration efforts stand as a model for grassroots ecological conservation, demonstrating how sustainable practices can revive degraded landscapes and secure local livelihoods.

Malachipada Protests

In Dhule district, Maharashtra, villagers from Malaichapada have been protesting since 2020 against the government's transfer of land to a de-addiction center operated by Vishwa Manav Ruhani Kendra, citing violations of the Panchayat Extension to Scheduled Area (PESA) Act of 2005. Their opposition intensified when a boundary wall was constructed without the gram sabha's consent, leading to road blockades and intervention by the local collector and the State Scheduled Tribe Commission. The villagers accuse the NGO of unauthorized mining, employing children instead of local laborers, and expanding operations beyond its original mandate. The land, initially acquired for the Panzara Dam in 1969, is now being demanded back by the gram sabhas of Pimpalner and Malaichapada, with concerns over procedural violations, land rights, and environmental degradation remaining at the forefront of their struggle.

Graphs

Water

Climate & Atmosphere

Forests & Ecology

Human Footprint

Sources

Aner dam wildlife sanctuary. 2023. InWikipedia.https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=A…

Aquifer Mapping and Management of Ground Water Resources: Dhule District, Maharashtra (Central Region, Nagpur). 2020-21. Central Ground Water Board, Department of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation, Ministry of Jal Shakti Government of India.https://www.cgwb.gov.in/old_website/AQM/NAQU…

Bose, M. 2021, August 6.77% of Maharashtra’s cropped area vulnerable to climate change: Study. Deccan Herald.https://www.deccanherald.com//india/77-of-ma…

Dhulia District, Maharashtra State Gazetteers (Reprint 2006). 1947. Gazetteer Department, Government of Maharashtra.https://gazetteers.maharashtra.gov.in/cultur…

Dutta, A. P (2019, September 10. Desertification in India: Soiled Dhule land is shallow, unfit for plantation. Down To Earth.https://www.downtoearth.org.in/climate-chang…

Kothari, S., Kujur, A., & Gupta, A. 2023, November. Tribals protest government land’s transfer to de-addiction center in Maharashtra’s Dhule | Dhule, Maharashtra. Land Conflict Watch.https://www.landconflictwatch.org/conflicts/…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.