Contents

- Physical Features

- Climate

- Geology

- Soil

- Minerals

- Rivers

- Botany

- Wild Animals

- Birds

- Forest Reserves

- Chaprala Wildlife Sanctuary

- Bhamragarh Wildlife Sanctuary

- Land Use

- Environmental Concerns

- Deforestation

- Water Scarcity

- Climate Change Vulnerability

- Environmental Efforts/Protests

- Amte’s Animal Ark

- The Impact of Mining on Gadchiroli's Indigenous Communities and Forests

- Maharashtra's First Elephant Reserve in Gondia and Gadchiroli Awaits Central Approval

- Mendha Lekha Village

- Struggles of a tiny village to get ownership of forest resources

- Environmental NGOs

- Arogya Sathi

- Graphs

- Water

- A. Rainfall (Yearly)

- B. Rainfall (Monthly)

- C. No. of Rainy Days in the Year (Taluka-wise)

- D. Evapotranspiration Potential vs Actual Numbers (Yearly)

- E. Annual Runoff

- F. Runoff (Monthly)

- G. Water Deficit (Yearly)

- H. Water Deficit (Monthly)

- I. Soil Moisture (Yearly)

- J. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Bore Wells

- K. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Dug Wells

- Climate & Atmosphere

- A. Maximum Temperature (Yearly)

- B. Maximum Temperature (Monthly)

- C. Minimum Temperature (Yearly)

- D. Minimum Temperature (Monthly)

- E. Wind Speed (Yearly)

- F. Wind Speed (Monthly)

- G. Relative Humidity

- Forests & Ecology

- A. Forest Area

- B. Forest Area (Filter by Density)

- C. Wildlife Projects (Area and Expenses)

- Human Footprint

- A. Nighttime Lights

- Sources

GADCHIROLI

Environment

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

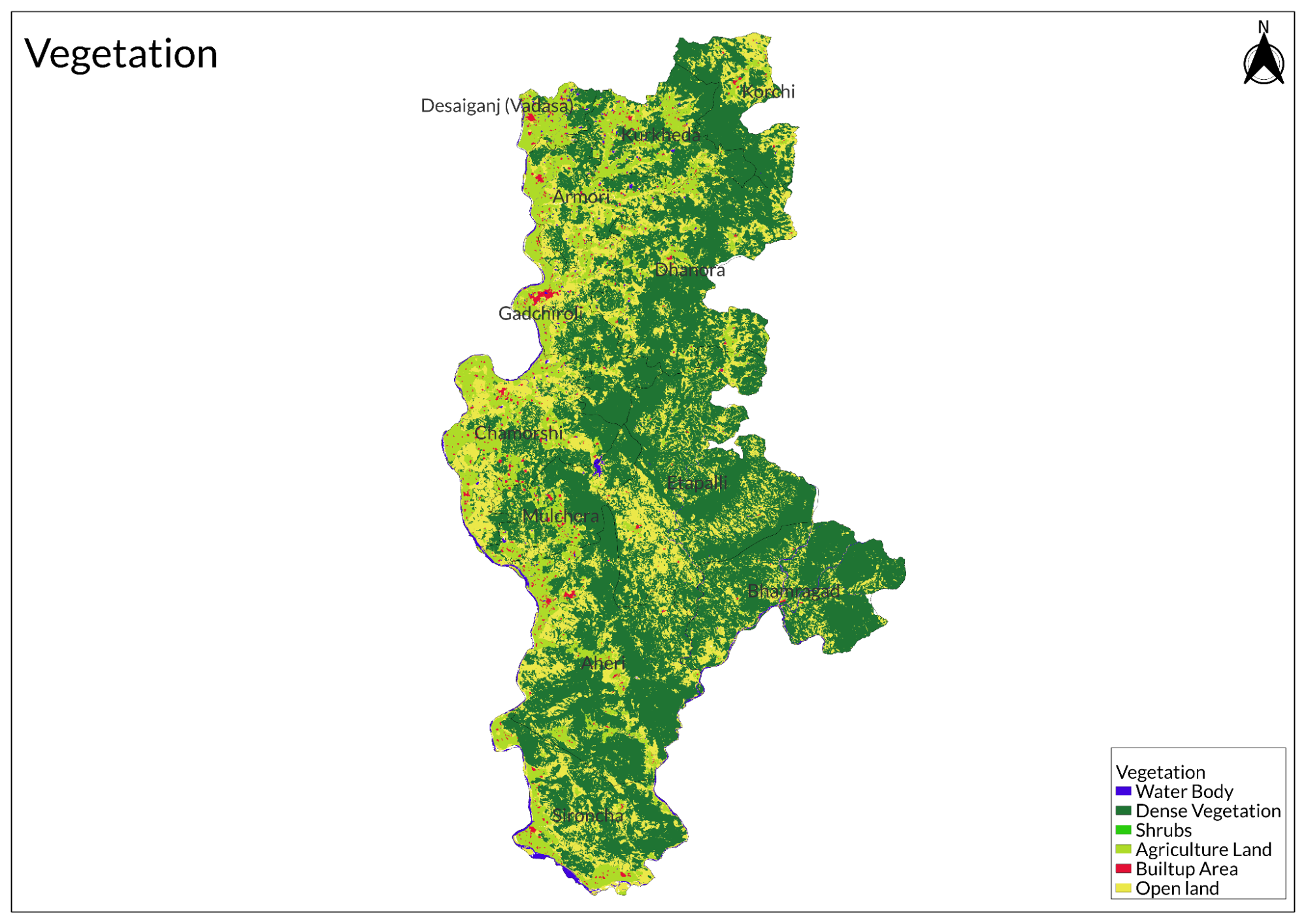

Gadchiroli district, situated in the northeastern region of Maharashtra, is a land of rich natural diversity and cultural significance. Spanning 14,412 square kilometers, it is often referred to as the "lungs of Maharashtra" due to its extensive forest cover, which accounts for nearly 69% of its total area. The district is characterized by its rugged terrain, highland plateaus, and dense forests, which support a vibrant ecosystem of flora and fauna. With major rivers like the Godavari, Indravati, and Wainganga shaping its landscape, Gadchiroli is home to diverse wildlife, including tigers, deer, and various bird species. Its unique geology, mineral resources, and tribal heritage contribute to its distinct identity.

Physical Features

Established on August 26, 1982, following its formation from Chandrapur district within Nagpur division, the district is is bordered by Chandrapur district to the south, Yavatmal district to the west, Adilabad district of Telangana to the north, and Bastar district of Chhattisgarh to the east. The district comprises 12 tehsils: Gadchiroli, Dhanora, Chamorshi, Mulchera, Desaiganj, Armori, Kurkheda, Korchi, Aheri, Sironcha, Etapalli, and Bhamragad.

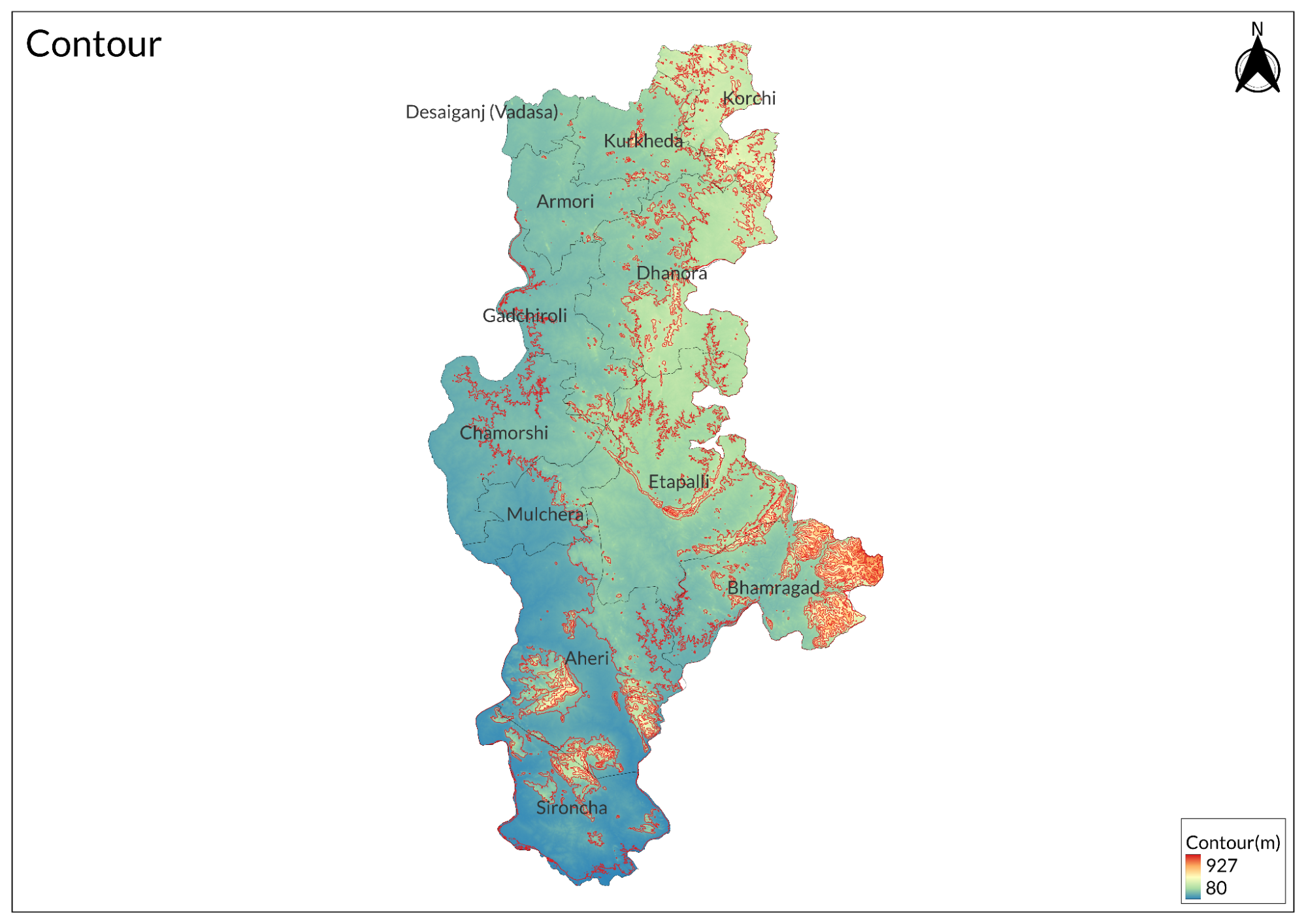

Often referred to as the "lungs of Maharashtra," Gadchiroli stands out for its extensive forest cover, comprising 68.81% of its land area. East of the Wainganga River, the district showcases a complex of highlands forming a plateau in its northern part. Gadchiroli, known for its diverse landscape, extends westward from Sironcha with prominent hill ranges like the Sirikonda range, reaching heights of approximately 1800 feet. Moving southwards from Sironcha, hills interspersed with breaks converge at the confluence of the Godavari and Indravati rivers. The lower taluks of Sironcha boast the district's highest peaks, including the Gadulgutta hills along the Godavari, spanning about 70 miles and rising to 3174 feet. These mountains feature rugged terrain and picturesque bamboo-lined footpaths, serving as primary routes through the area. The plateau is dotted with numerous hills, such as Bhamaragad, Tipagad, Palasgad, and Surjagad lies in the East of the district and soar up to 2000 feet. Moving south towards Aheri village, the terrain becomes more rugged, with hills rising between 2000 to 3000 feet.

Climate

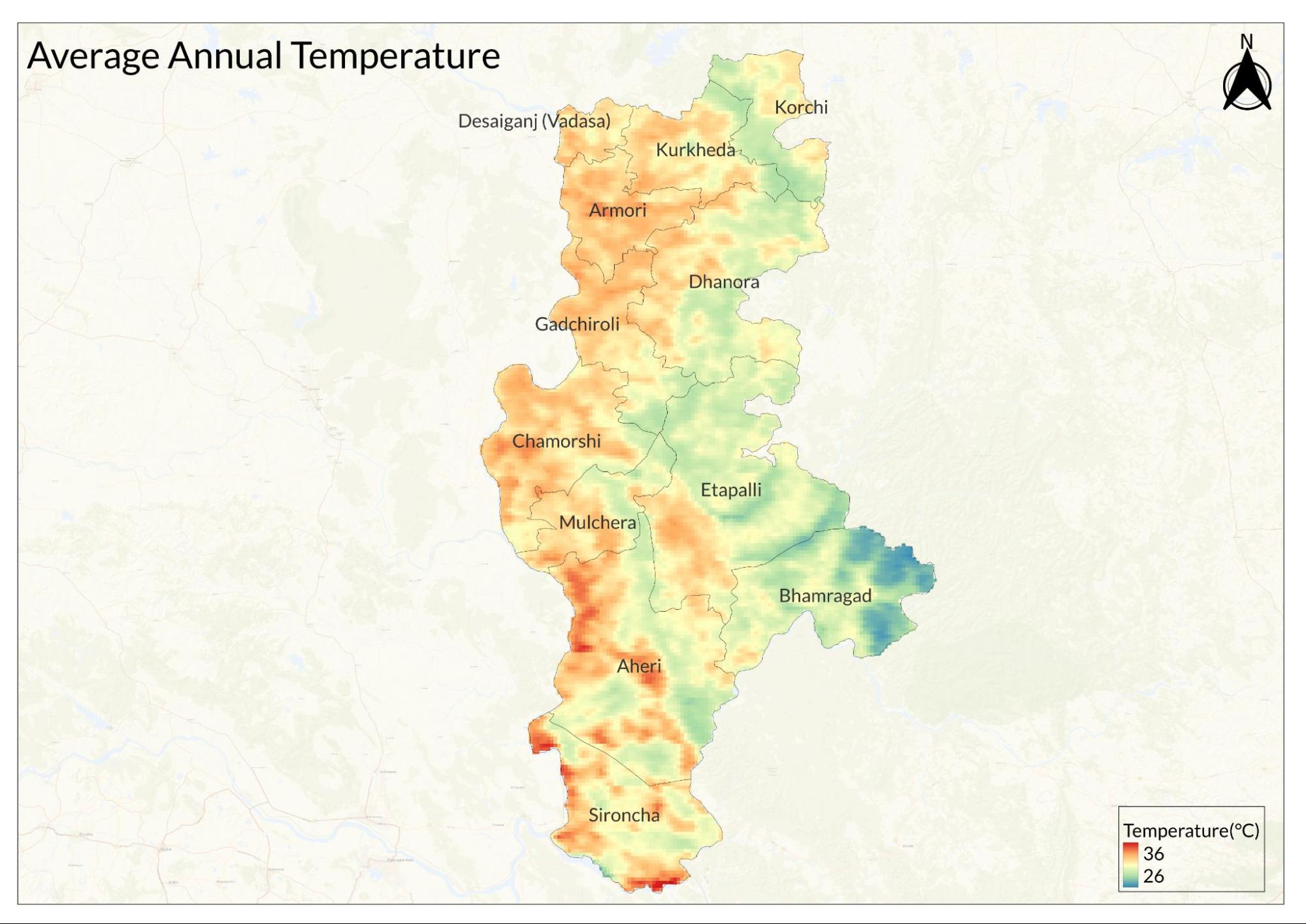

Gadchiroli District has a tropical wet-and-dry climate, with dry conditions prevailing for most of the year. The average temperature varies between 27°C and 33°C. The district experiences hot summers from March to May, with May being the hottest month, when temperatures range from 28.5°C to 44.9°C. Winter lasts from December to February, with temperatures gradually declining from October onwards, making December the coldest month of the year, with temperatures ranging from 11.5°C to 29.1°C.

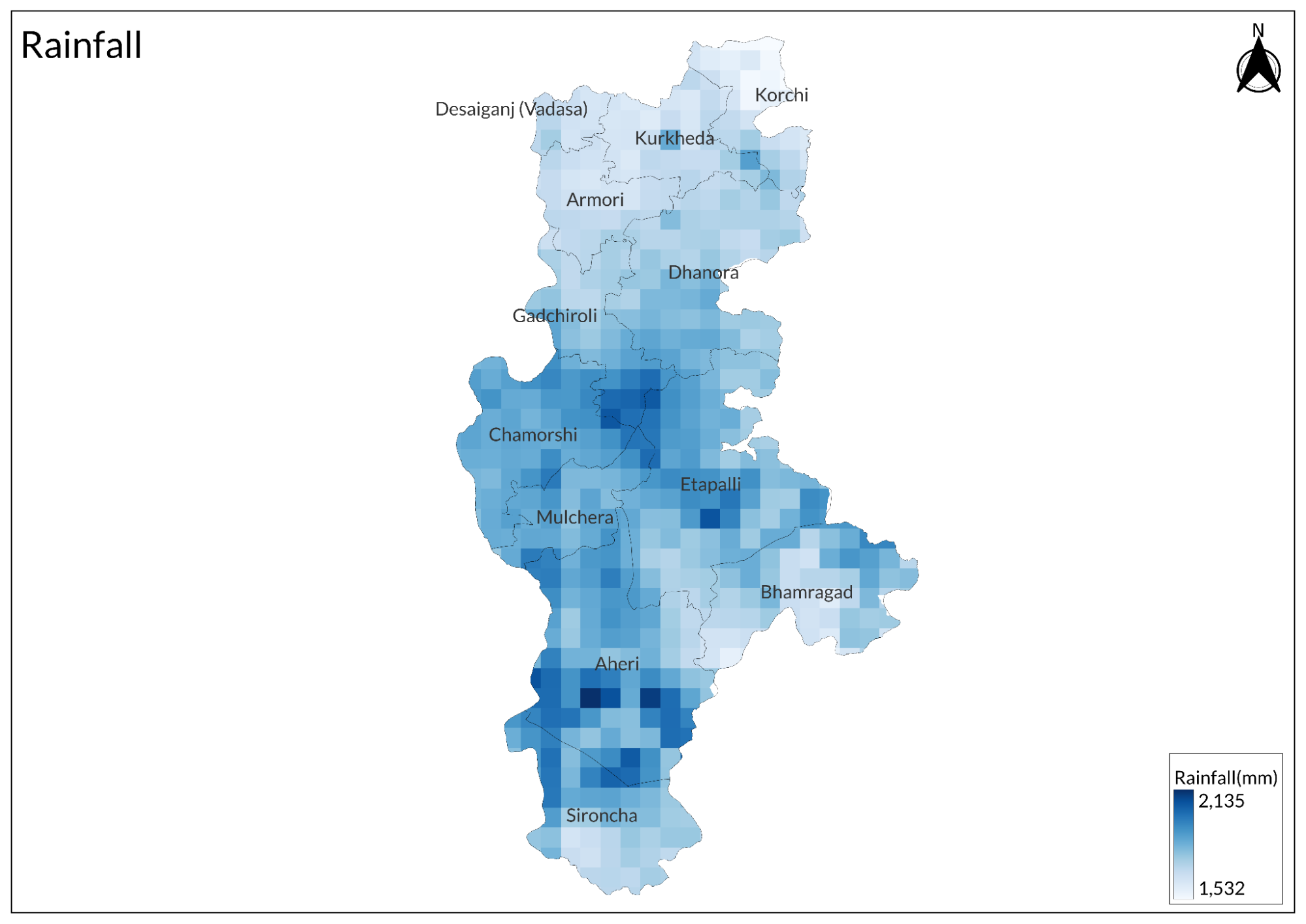

From June to October, the monsoon season begins, and the climate becomes warm and humid, characterized by heavy and consistent rainfall totaling an average of 1,314 mm annually, with 80 percent of this occurring during this period.

Geology

The district is unique in Maharashtra in that the entire area is primarily occupied by metamorphic and igneous rocks, along with sedimentary rocks in the southern part. The northern part of the tehsil is predominantly composed of crystalline rocks. The rock types encountered belong to the Bengpal Group of Archean age, which is 4 to 2.5 billion years old, and the Bailadila Group of Paleo-Proterozoic age, which is 2.5 to 1.6 billion years old.

Soil

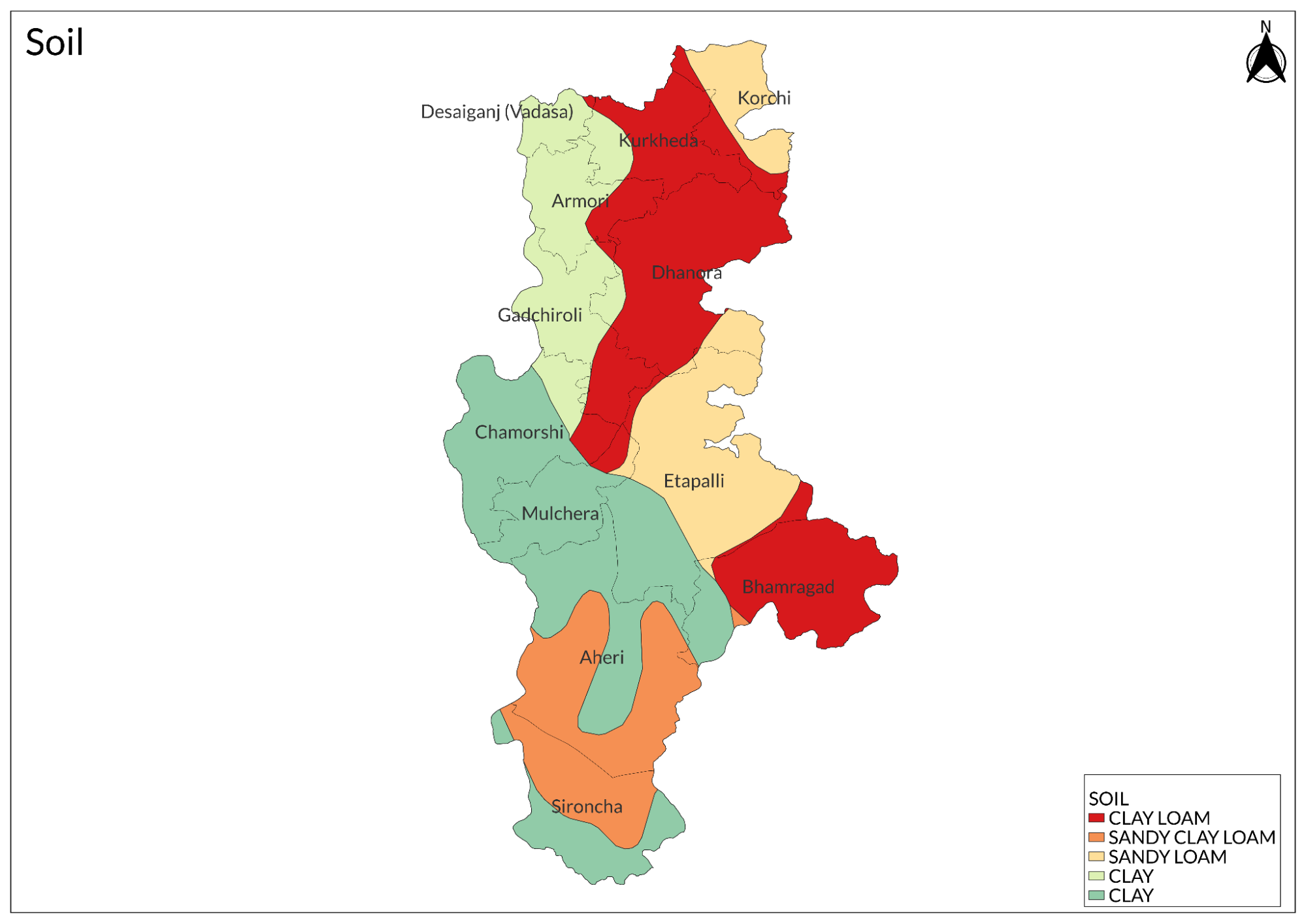

The major portion of the soil is derived from red lateritic soil and yellowish-brown soil. Medium black soil is prevalent in most parts of Dhanora, Kurkheda, Etapalli, Aheri, and some areas of the remaining block, followed by deep black soil.

Minerals

Baryte, dolomite, quartz, and colored granite, along with iron ore deposits, are found in the Surjagad and Bhamragad areas of the district. Limestone deposits are located in the Devalmali and Katepalli areas, while diamonds are observed in Vairagad.

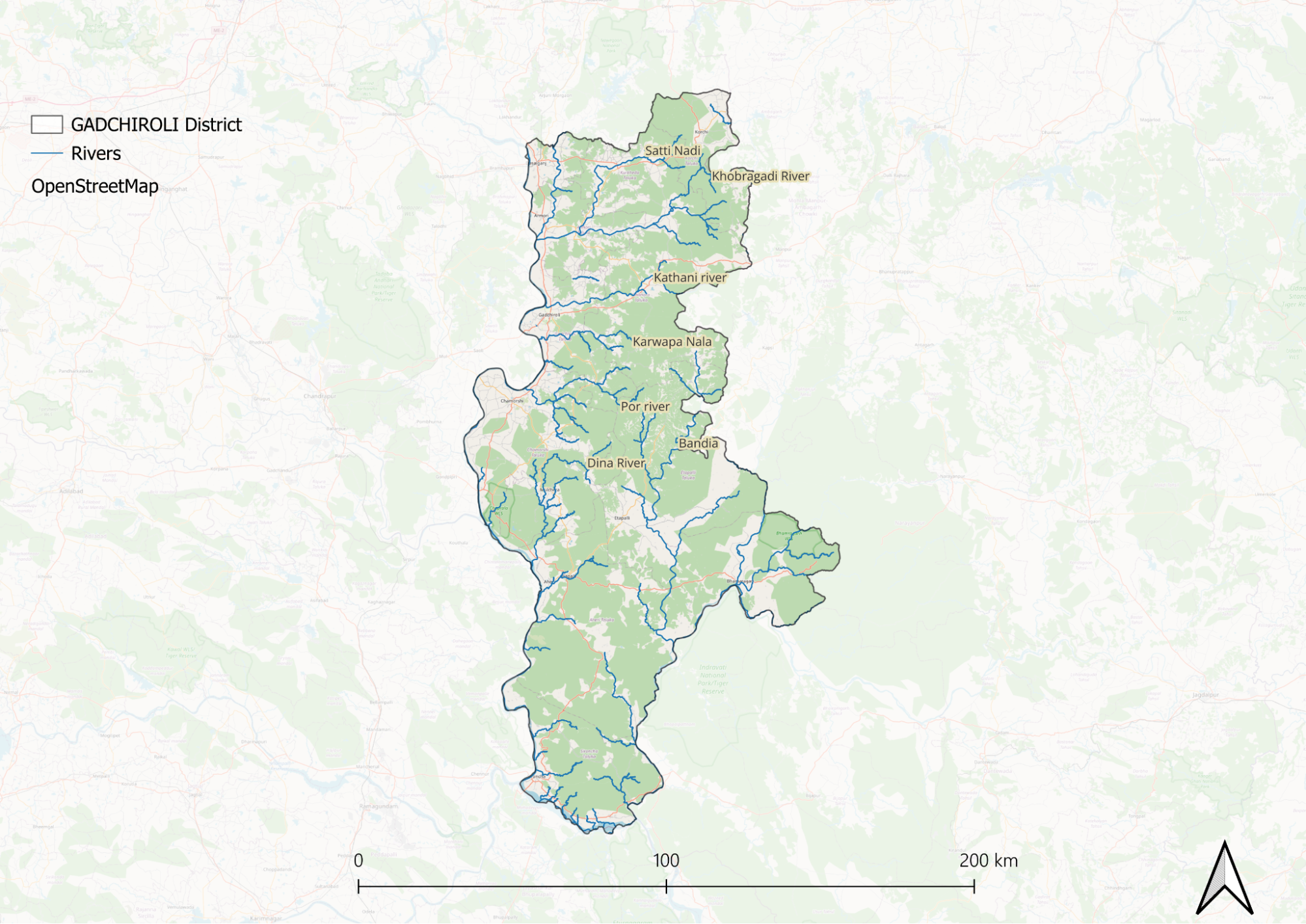

Rivers

The district is bordered by three principal rivers: the Pranitha River to the west, the southwest-to-south flowing Godavari, and the southeast-bound Indravati River. The western boundary, extending for 225 km, is formed by the flow of the Wainganga River, which divides the Chandrapur and Gadchiroli districts. Further downstream, the Wainganga joins the Wardha River in Chandrapur district, and together they form the Pranitha River, which marks a southwestern boundary of 190 km for Gadchiroli district.

The Dina River, originating from Dina Dam near Regadi village, is the main tributary of the Pranitha River, joining it near Rampur Chak village. Near Sironcha, the Pranitha merges with the Godavari and takes on its name. The volume of these combined rivers is further increased by the influx of the Indravati. The Indravati rises in the highlands of Tohamal in the Eastern Ghats and enters this district east of Aheri village; it initially flows due west but later turns south before merging with the Godavari after a total course of about 275 miles.

Before the Indravati confluences with its tributaries—the Parlkota River (Nimbra) and Pamulgautam River (Kotari)—these join near Bhamragad at a confluence point known as Triveni Sangam. This area is scenic and popular for sunset views, where wildlife such as Aswal and Harin can also be observed. The entire Gadchiroli district lies within the drainage basin of the Godavari River.

At the southwestern boundary of the district, near Sironcha, the Godavari enters and flows eastwards for about 50 km along the southern boundary. After its confluence with the Indravati at the southeastern corner, the Godavari turns south into Andhra Pradesh.

Botany

Timber trees are primarily found in the forested areas of the district. Teak trees are located in the Aheri and Allapalli forest regions and are renowned for their high-quality timber. Saj trees grow in Aheri, Alapalli, and Moharli forests. Additionally, Sagwan (teak) and bamboo trees are commonly cultivated by farmers.

Wild Animals

The district is home to a rich variety of wildlife, including two species of monkeys: the Bandar and the langur. Bandars are found primarily along the southern and eastern borders of Sironcha tahsil, near the Godavari and Indravati rivers. In contrast, langurs are widely distributed across open areas and forests throughout the district, where they are notorious for damaging crops and fruit trees.

In Aheri village, small herds of Barasingha can be observed, raising questions about their local presence. The mouse deer is sighted in parts of Aheri and Ghot villages, while the barking deer can be found near the Bhamragad Sangam area. The Chapala Wildlife Sanctuary serves as a haven for various wild animals, including tigers, Harin (chital), Chitta (leopard), Jungali Manjar (wild boar), Aswal (wild dog), deer, and Sambar. This diverse range of species contributes to the rich biodiversity of the region, making it an important wildlife habitat within the district.

Birds

The district is home to a rich variety of wildlife, including two species of monkeys: the Bandar and the langur. Bandars are restricted to the southern and eastern borders of Sironcha tahsil along the Godavari and Indravati rivers. In contrast, langurs are widely distributed across open areas and forests throughout the district, where they are notorious for damaging crops and fruit trees.

In Aheri village, small herds of Barasingha can be found, raising questions about their local presence. The mouse deer is sighted in parts of Aheri and Ghot villages, while the barking deer can be found near the Bhamragad Sangam area. The Chapala Wildlife Sanctuary serves as a haven for a variety of wild animals, including tigers, Harin (chital), Chitta (leopard), Jungali Manjar (wild boar), Aswal (wild dog), deer, and Sambar. This diverse range of species contributes to the rich biodiversity of the region, making it an important wildlife habitat within the district.

Forest Reserves

Chaprala Wildlife Sanctuary

Chaprala Wildlife Sanctuary is situated in the Chamorshi Taluka of Gadchiroli district. Spanning approximately 140 km², it features thick forest growth interspersed with occasional stretches of grasslands. The sanctuary is flanked by the Markhanda and Pedigundam hills to the northeast and south, while the Pranhita River flows along its western boundary. It is located at the confluence of the Wardha and Wainganga rivers. During the monsoon season, river water swells and enters the sanctuary primarily through numerous nallahs. Along with backwater, a variety of fish, prawns, and turtles also enter the sanctuary.

Bhamragarh Wildlife Sanctuary

Bhamragarh Wildlife Sanctuary spans approximately 104 square kilometers within the Sahyadri mountain range. Known for its stunning landscapes and rich biodiversity, the sanctuary features dense forests of deciduous trees, bamboo groves, and grasslands that provide habitat for a variety of wildlife. Visitors can spot tigers, leopards, sloth bears, gaurs, and various species of deer. Birdwatchers can delight in observing peafowls, eagles, hornbills, and more.

The sanctuary offers well-marked trekking trails and strategically placed watchtowers for wildlife viewing and photography. It provides a peaceful atmosphere ideal for nature walks and picnics as well as cultural explorations of nearby Gond and Madiya tribal villages. The winter months from November to February are recommended for visits due to pleasant weather and optimal wildlife sightings. Basic amenities and knowledgeable guides are available to enhance the experience.

Land Use

Environmental Concerns

Deforestation

Deforestation in Gadchiroli district has become a pressing concern, as highlighted by the India State of Forest Report 2021, which revealed a loss of over 4 sq km of forest area despite Maharashtra's overall increase of 30 sq km in forest cover. Encroachments under the Forest Rights Act of 2006 are cited as a major factor behind this decline, posing a threat to the region’s significant tiger population and fragile ecosystems. Additionally, Gadchiroli and Chandrapur are classified as extremely fire-prone areas, further exacerbating conservation challenges. While officials acknowledge encroachments as a critical issue, environmental advocates question claims of high plantation survival rates amid ongoing deforestation driven by infrastructure projects, raising concerns about the effectiveness of current conservation efforts.

Water Scarcity

Gadchiroli district in Maharashtra faces severe water scarcity due to climate change, inadequate water management, and excessive groundwater extraction. Irregular rainfall patterns and delayed monsoons have dried up reservoirs and hindered aquifer recharge, while poor infrastructure and government oversight have exacerbated the crisis. The overuse of groundwater, driven by high agricultural demand and the cultivation of water-intensive crops like sugarcane, has further strained the region’s water resources. In remote areas like Kaorchi Taluk, villagers must walk through dense jungles to access wells, risking snake and scorpion bites, while local women rely on hand-powered pumps or pulley systems to secure water, underscoring the daily hardships faced by the community.

Climate Change Vulnerability

Environmental Efforts/Protests

Amte’s Animal Ark

The Animal Ark Rescue Centre in Hemalkasa, Gadchiroli, founded by Prakash Amte over 40 years ago, has gained recognition for its unconventional approach to wildlife conservation. Unlike traditional zoos, it serves as a shelter for orphaned animals, earning accolades, including a seat on the National Tiger Conservation Authority. However, its methods have often led to conflicts with regulatory authorities. Recently, the Central Zoo Authority (CZA) questioned its legitimacy after a film showed Amte’s granddaughter handling venomous snakes, citing violations of the Wildlife Protection Act. In response, Amte clarified that the center provides essential care for orphaned animals, agreeing to cease public handling and expand facilities while emphasizing its role in wildlife education.

Regulatory challenges are not new for Amte, which previously faced similar scrutiny in 2003 when the Maharashtra forest department attempted to confiscate animals. His commitment to animal welfare was evident when he threatened to return his Padma Shri if his work was obstructed. The center has also faced criticism for acquiring animals without prior approval, but Amte argues that immediate care is necessary for their survival. Despite these challenges, the Animal Ark remains a crucial institution, blending conservation with community education while navigating the complexities of wildlife regulations in India.

The Impact of Mining on Gadchiroli's Indigenous Communities and Forests

Mining in Gadchiroli, Maharashtra, has sparked intense opposition from the indigenous Madia Gond communities, who depend on the region’s dense forests for their livelihoods and cultural identity. Government-approved mining projects, such as those granted to Gopani Iron and Power (India) Ltd. (153 hectares) and Lloyd Metals (384.04 hectares), are part of a broader push that threatens nearly 15,000 hectares of dense forest and indirectly affects another 16,000 hectares. The Surjagad Hills, where these projects are concentrated, hold deep spiritual significance for the Madia Gonds, who conduct annual pilgrimages there. However, legal protections under the Forest Conservation Act and the Forest Rights Act have been ignored, as mining leases were renewed without obtaining prior informed consent from local gram sabhas. Protests against mining have persisted since 1993, yet operations commenced in 2016, fueling concerns about ecological degradation and loss of traditional land rights.

The justification for these projects often includes promises of employment, but the Madia Gonds, who have sustained themselves through agriculture, reject exploitative labor in hazardous conditions. Furthermore, opposition to mining is frequently dismissed as "Maoist extremism," leading to repression and legal action against activists. Despite these challenges, the community remains resolute in its resistance, utilizing democratic avenues such as elections to gain representation and advocate for their rights. Many local leaders have won seats on councils, prioritizing indigenous interests over corporate expansion, highlighting an ongoing struggle to balance economic development with environmental and cultural preservation.

Maharashtra's First Elephant Reserve in Gondia and Gadchiroli Awaits Central Approval

Maharashtra is awaiting central approval for its first elephant reserve, proposed in August 2023 to cover over 1,400 square kilometers in Gondia and Gadchiroli districts. The initiative stems from the observation of elephants migrating from Chhattisgarh and Odisha since 2021, with a small population now residing in the region. While some experts argue that the current population of around 20–30 elephants is too small for a viable reserve, others believe it would aid conservation efforts, as elephants are gradually reclaiming parts of their historic range. Aritra Kshettry from World Wildlife Fund, India, highlights the increasing elephant presence in Central India, with migration patterns suggesting further expansion into Maharashtra. Given the state's suitable forest habitats and connectivity with Chhattisgarh’s elephant population, experts advocate for a landscape-based conservation approach that integrates protected areas and agricultural landscapes to support long-term population growth.

Mendha Lekha Village

Mendha Lekha, a small Gond tribal village in Maharashtra’s Gadchiroli district, has emerged as a model of self-governance and collective prosperity. Surrounded by dense forests rich in teak and bamboo, the village has long relied on these resources for sustenance. In the early 2000s, it became the first in India to secure community forest rights, allowing villagers to sustainably harvest bamboo, generating an annual income of over Rs 1 crore. This financial success, however, is rooted in a deeper ethos of shared ownership Years ago, villagers pledged their private lands to the community, fostering a system where profits are equally distributed and investments are made in education, healthcare, and infrastructure.

Mendha Lekha's journey toward autonomy was catalyzed by a 1985 victory against a hydroelectric project that threatened their way of life. Inspired by the Gramdan movement, the village pursued official recognition under the Maharashtra Gramdan Act of 1964, requiring 75% of landowners to voluntarily surrender land to the gram sabha. Despite fulfilling this condition in 2013, bureaucratic delays persisted until September 2023, when the Bombay High Court ruled in their favor, leading to their formal recognition as a gram panchayat in February 2024. This milestone marked the restoration of customary rights over their forests, once controlled by the government post-independence.

Beyond economic empowerment, Mendha Lekha prioritizes sustainability and community welfare. Decisions on forest use, farming, and resource management are made collectively, ensuring ecological balance while fostering a strong sense of belonging. The village’s thriving schools, improved infrastructure, and aspirations for bamboo-processing units reflect its vision for self-reliance. Despite external challenges, including Maoist insurgency threats, Mendha Lekha continues to chart an alternative path to prosperity—one where success is measured by communal harmony, sustainable livelihoods, and deep reverence for nature.

Struggles of a tiny village to get ownership of forest resources

In Ghati village, Maharashtra’s Gadchiroli district, residents have been fighting for their community forest rights under the Forest Rights Act (FRA) since 2009, inspired by the success of Mendha Lekha. Their struggle intensified in 2010 when the forest department marked trees for felling without consulting them, prompting villagers to stage a hunger strike. Although they secured a written assurance that no trees would be cut without their consent, their eventual forest rights claim was approved with significant reductions in land area and authority. Feeling betrayed, the villagers took matters into their own hands, confiscating illegally felled timber and blocking multiple attempts by the department to collect it, leading to repeated stand-offs.

At the heart of the conflict is a legal dispute over ownership and rights: the forest department claims villagers only have rights over minor forest produce (MFP), while the community argues that felled trees also constitute valuable MFP and require their consent for removal. As tensions escalate, the police remain caught between conflicting legal interpretations, and the village gram sabha has even decided to levy fines against the department for unauthorized timber felling. The standoff highlights the broader struggle of tribal communities asserting their constitutional rights over ancestral forests against state-controlled conservation policies.

Cultural Connections with Nature

Venkatapur, a village located just 30 kilometers from Aheri taluka, features a remarkable water tank that exhibits an unusual phenomenon: when people clap their hands, the water in the tank bubbles. The villagers themselves are unsure of the exact cause of this occurrence. For the tribal communities in the district, nature holds immense significance, and this water body is also regarded as a sacred site.

Environmental NGOs

Arogya Sathi

Arogya Sathi, a not-for-profit organization founded in 1984 by Dr. Satish Gogulwar and Shubhada Deshmukh, focuses on empowering women, tribal populations, farmers, and marginalized groups through a Gandhian and Vinoba Bhave-inspired approach. Committed to holistic health, livelihood, water access, and self-governance, the organization aligns its efforts with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), contributing to seven of the 17 goals. It promotes environmental conservation, local governance, and sustainable development, with key initiatives including community-based rehabilitation for persons with disabilities and supporting non-timber forest products (NTFPs) as alternative livelihoods. Through grassroots engagement, Arogya Sathi enables communities to manage resources and improve their overall well-being.

Graphs

Water

Climate & Atmosphere

Forests & Ecology

Human Footprint

Sources

Amhi amchya arogyasathi. Amhi Amchya Arogyasathi.http://arogyasathi.org/

Animal Ark Rescue Centre, Gadchiroli: An animal centre that bothers the same authorities that reward it. 2018, January 17. The Indian Express.https://indianexpress.com/article/india/anim…

Bose, M. 2021, August 21..77% of Maharashtra’s cropped area vulnerable to climate change: Study. Deccan Herald.https://www.deccanherald.com//india/77-of-ma…

Broome, N. P., & Raut, M. 2017, July 4.Mining in Gadchiroli – building a castle of injustices. Ecologise.https://ecologise.in/2017/07/04/mining-gadch…

Pallavi, A. 2011, August 19. A tale of two interpretations. Down To Earth.https://www.downtoearth.org.in/environment/a…

Pinjarkar, V. 2022, January 14. Gadchiroli, Chandrapur lost over 18 sq km forest cover in 2 years.The Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/nag…

Tehsils and Circle Offices. 2025, March 6. District Gadchiroli, Government of Maharashtrahttps://gadchiroli.gov.in/tehsil/

‘Doorstep water’ now a reality for remote Indian villages. 2022, October. Grundfos .https://www.grundfos.com/about-us/cases/door…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.