Contents

- Climate

- Geology

- Soil

- Rivers

- Flora and Fauna

- Cultural Connections With Nature

- Aghera

- Waghoba

- Land Use

- Environmental Concerns

- Loss of Mangroves

- Air Pollution

- Water Pollution

- Effects of Climate Change

- Conservation Efforts/Protests

- Aarey Forests

- Environmental NGOS

- Bombay Environmental Action Group

- NAGAR

- NAGAR, established in 2000, addresses various urban environmental challenges such as solid waste management and air pollution. They advocate for improved governance policies and engage in public awareness campaigns to foster community involvement in...

- The Navi Mumbai Environment Preservation Society (NMEPS)

- Vanashakti

- Vanashakti, established in 2006, focuses on the conservation of forests, mangroves, and wetlands. The organization emphasizes environmental education, legal advocacy, and sustainable livelihood programs for communities dependent on these ecosystems....

- Waghoba Habitat Foundation

- Graphs

- Water

- A. Rainfall (Yearly)

- B. Rainfall (Monthly)

- C. No. of Rainy Days in the Year (Taluka-wise)

- D. Evapotranspiration Potential vs Actual Numbers (Yearly)

- E. Annual Runoff

- F. Runoff (Monthly)

- G. Water Deficit (Yearly)

- H. Water Deficit (Monthly)

- I. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Dug Wells

- Climate & Atmosphere

- A. Maximum Temperature (Yearly)

- B. Maximum Temperature (Monthly)

- C. Minimum Temperature (Yearly)

- D. Minimum Temperature (Monthly)

- E. Wind Speed (Yearly)

- F. Wind Speed (Monthly)

- Forests & Ecology

- A. Forest Area

- B. Forest Area (Filter by Density)

- C. Wildlife Projects (Area and Expenses)

- Human Footprint

- A. Nighttime Lights

- Sources

MUMBAI SUBURBAN

Environment

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Mumbai Suburban's physical geography is rooted in its historical identity as part of Salsette Island, known traditionally as Shahashasti. This region originally encompassed 66 villages, stretching across what are now the modern areas of Khar, Dahisar, Mulund, Borivali, and extending to Thane. Over time, this unified geographical entity has been fragmented into various administrative divisions, though its underlying physical characteristics remain evident.

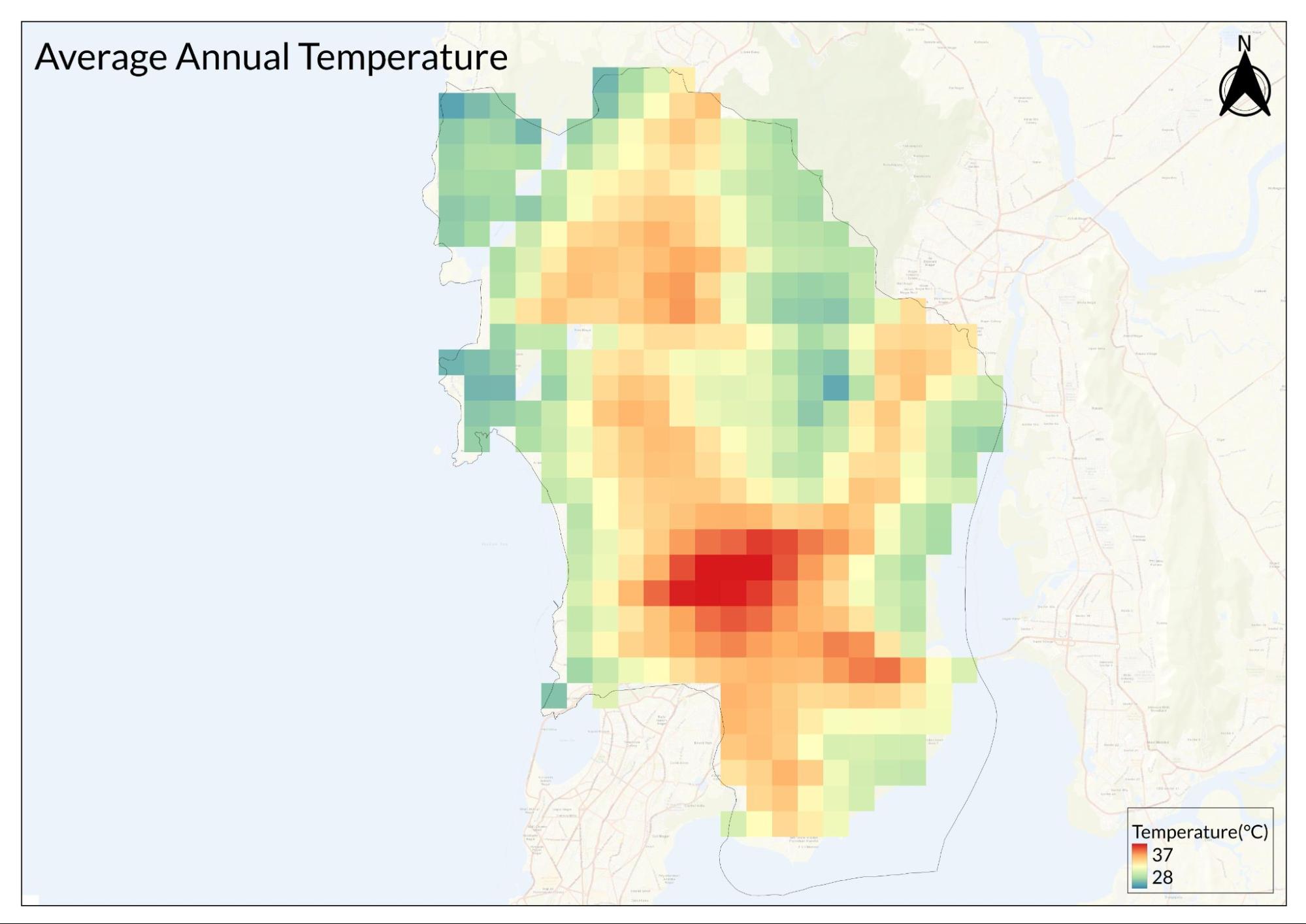

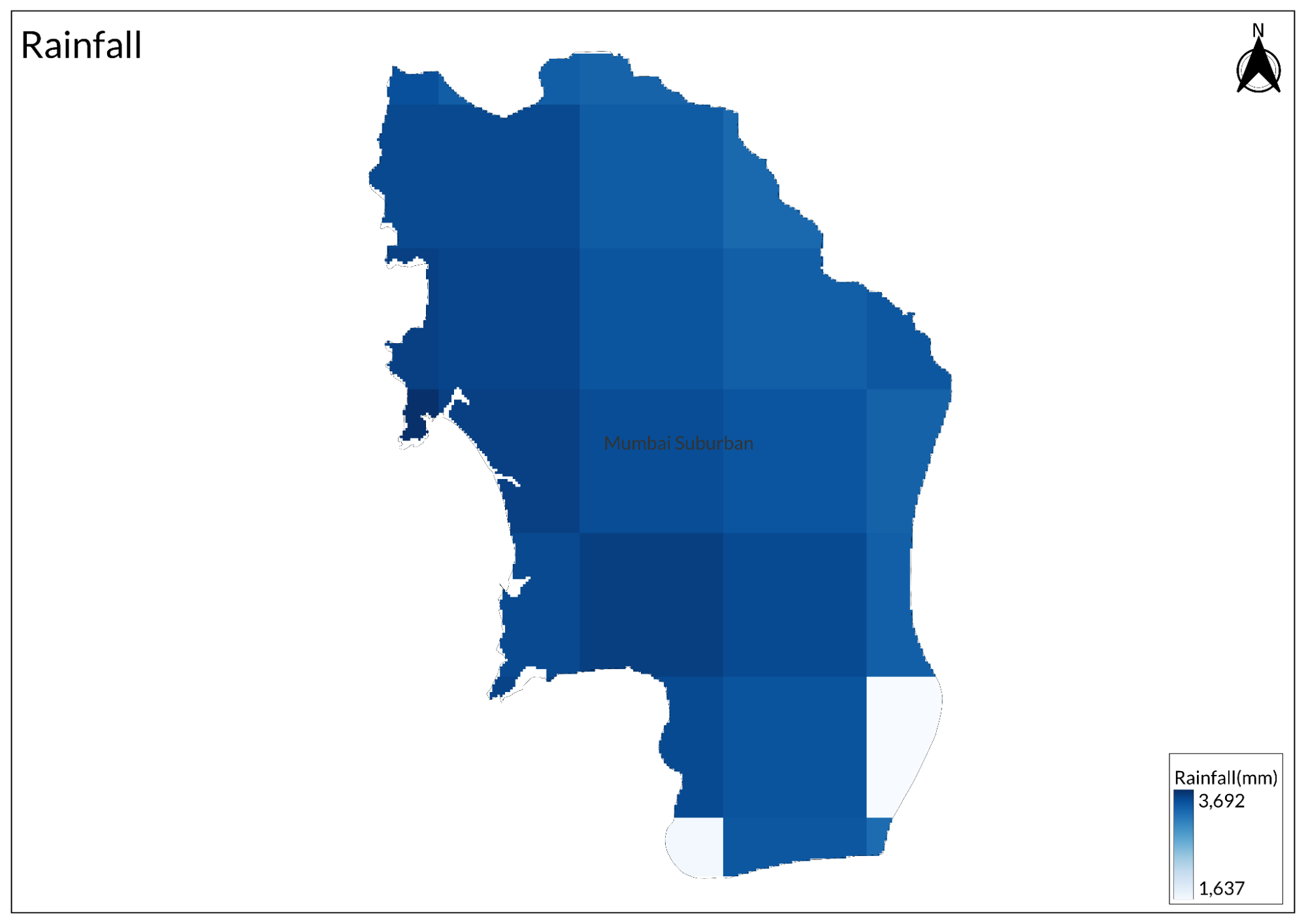

Climate

Mumbai Suburban's climate patterns have shown significant changes over recent years, particularly in terms of rainfall distribution and intensity. According to data from the India Meteorological Department (IMD), the district has experienced a notable shift in its precipitation patterns over the past decade. The area typically experiences multiple categories of rainfall events throughout the year, including heavy rainfall (64.5 - 115.5 mm), very heavy rainfall (115.6 - 204.4 mm), and extremely heavy rainfall events (exceeding 204.5 mm). On average, the district sees about six heavy rainfall events, five very heavy rainfall events, and four extremely heavy rainfall events annually.

A significant trend has emerged in recent years where the overall monsoon rainfall volume has decreased, yet the frequency of extreme rainfall events has increased. This has created a climate pattern characterized by longer dry periods punctuated by intense, short-duration downpours. This shift in rainfall distribution has important implications for the district's infrastructure and daily life.

The district's climate is particularly complex due to its coastal location, where rainfall patterns interact with tidal movements. Flooding in Mumbai Suburban occurs through a combination of two primary factors: heavy rainfall and high tides along the coastal shores. These high tides are especially pronounced during Amavasya and Gurupoornima, and when they coincide with heavy rainfall, they can lead to significant flooding events.

The impact of these climate patterns varies significantly across different areas of the district. Low-lying regions, particularly areas like Kurla, experience frequent waterlogging during heavy rainfall events. The situation is often exacerbated in these areas when heavy rainfall coincides with high tides, leading to severe flooding and disruption of daily activities. In contrast, areas at higher elevations tend to be less affected by waterlogging, though they may face other climate-related challenges.

The changing climate patterns have put considerable strain on the district's infrastructure, which wasn't originally designed to handle such extreme weather events. This is particularly evident in how the district's drainage systems cope with intense rainfall. The issue is compounded in areas where urban development has altered natural drainage patterns or where infrastructure hasn't kept pace with climate changes.

Transportation systems are particularly vulnerable to these climate patterns. Heavy rainfall events often lead to disruptions in suburban train services, flooding of roads, and general mobility challenges across the district. These disruptions have significant implications for the daily lives of residents and the overall functioning of the district.

The climate's impact on urban life has led to various adaptation measures and infrastructure modifications throughout the district. However, the increasing unpredictability of rainfall patterns and the growing frequency of extreme weather events continue to pose challenges for urban planning and disaster management in Mumbai Suburban.

Understanding these climate patterns is crucial for future urban planning and development in the district. The challenge lies in adapting infrastructure and urban systems to handle both extended dry periods and intense rainfall events, while also accounting for the coastal influence on local weather patterns.

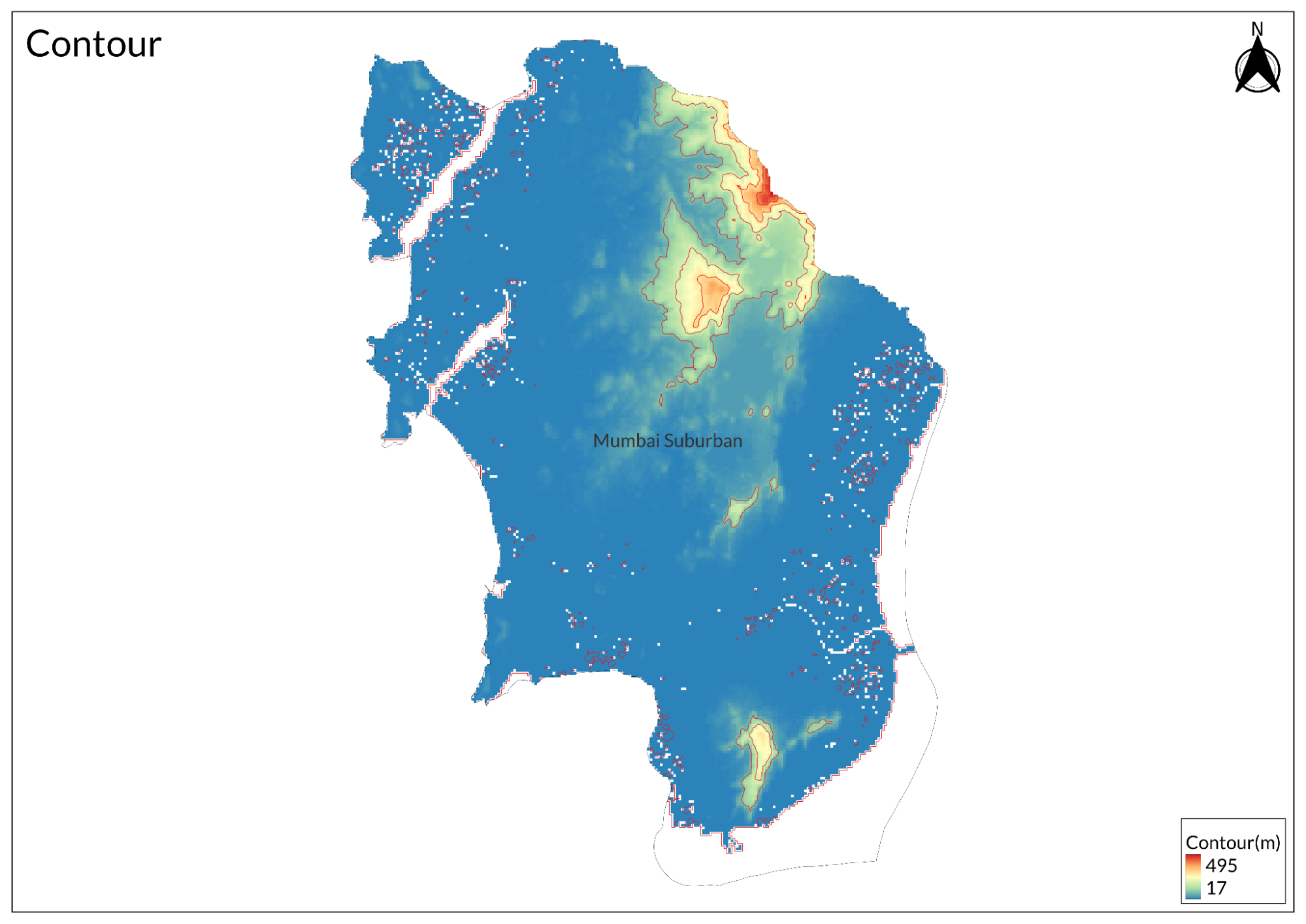

Geology

The geological foundation of Mumbai Suburban district is deeply rooted in its classification as part of the 'Deccan Trap', a significant geological formation that defines much of the region's physical characteristics. This formation, dating back approximately 65 million years, is characterized by extensive basaltic lava flows that have shaped the landscape we see today. The term 'Deccan Trap' itself signifies the step-like terrain created by multiple layers of volcanic material, a testament to the region's volcanic history.

Within this geological framework, certain areas stand out for their unique features and scientific significance. The Tulsi Lake area and the Kanheri caves region are particularly notable for their prominent deposits of volcanic agglomerate. These locations likely served as volcanic centers during the formation period, as evidenced by the distinctive rock formations found there. The presence of these formations provides valuable insights into the region's volcanic past and the processes that shaped its current landscape.

The volcanic history of the area is particularly evident in the rock formations that can be observed throughout the district. These formations show clear signs of rapid cooling patterns, especially where molten lava came into contact with water. This interaction created distinctive rock structures that remain visible today, offering a glimpse into the dramatic geological processes that occurred millions of years ago. The distribution of pyroclastic rocks throughout the region further supports the evidence of significant volcanic activity in the area's distant past.

The district's geological heritage extends beyond just its rock formations. The landscape showcases a complex interplay of various geological features, including basaltic flows that form the primary bedrock, pyroclastic rocks that originated from volcanic activity, and volcanic agglomerate deposits that tell the story of ancient volcanic eruptions.

Conservation of these geological features presents both challenges and opportunities. While some sites are well-protected within designated conservation areas, others face pressure from urban development. The document emphasizes that geo-sites are ubiquitous, much like cultural sites, and add significant value to the region's history and locality. However, many of these sites go unnoticed in the daily hustle and bustle of urban life, highlighting the need for greater awareness and preservation efforts.

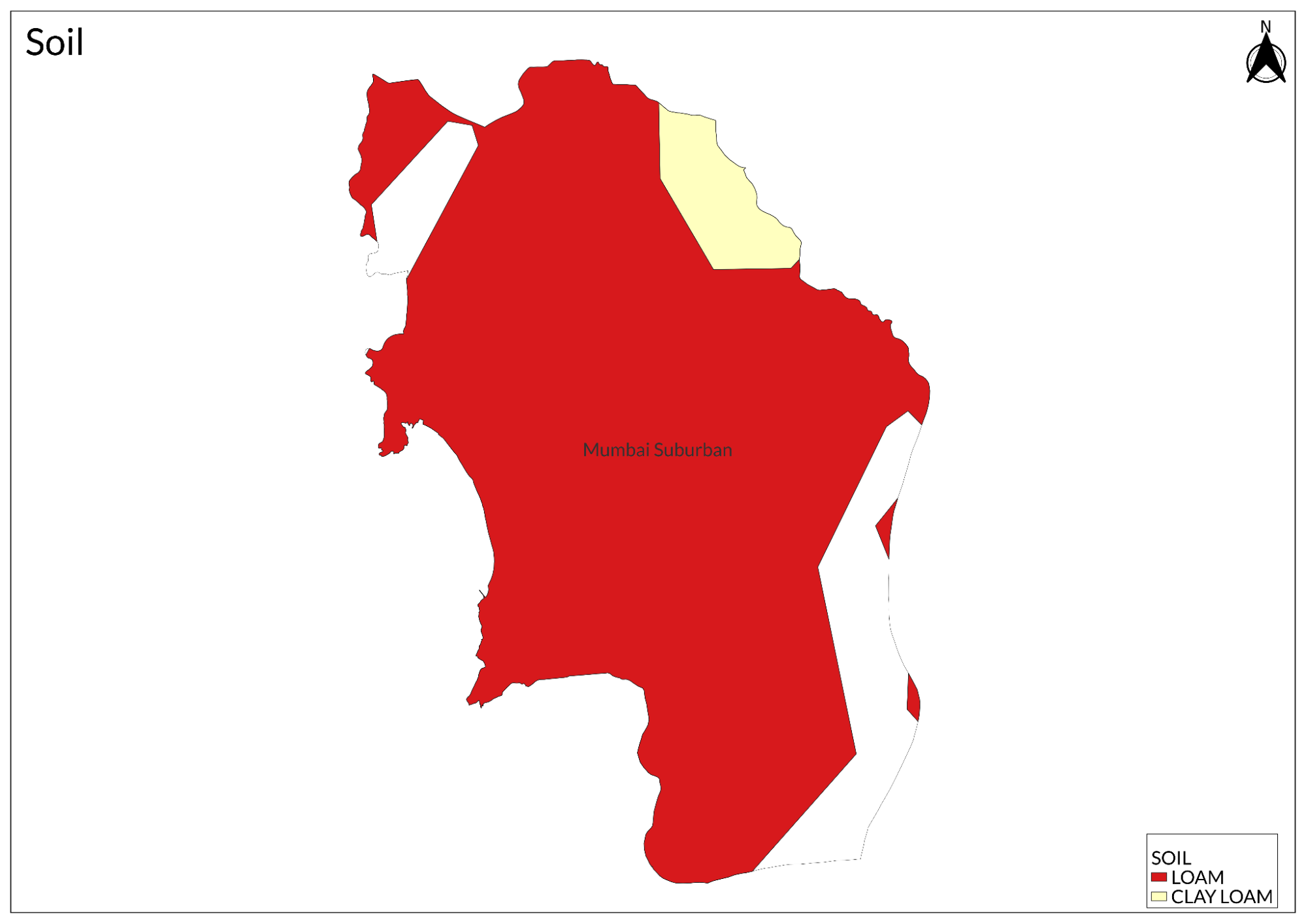

Soil

Mumbai Suburban's soils stem from the Deccan Trap formation. These soils come from basaltic lava flows that date back 65 million years, giving them mineral properties that influence the region's vegetation and land use.

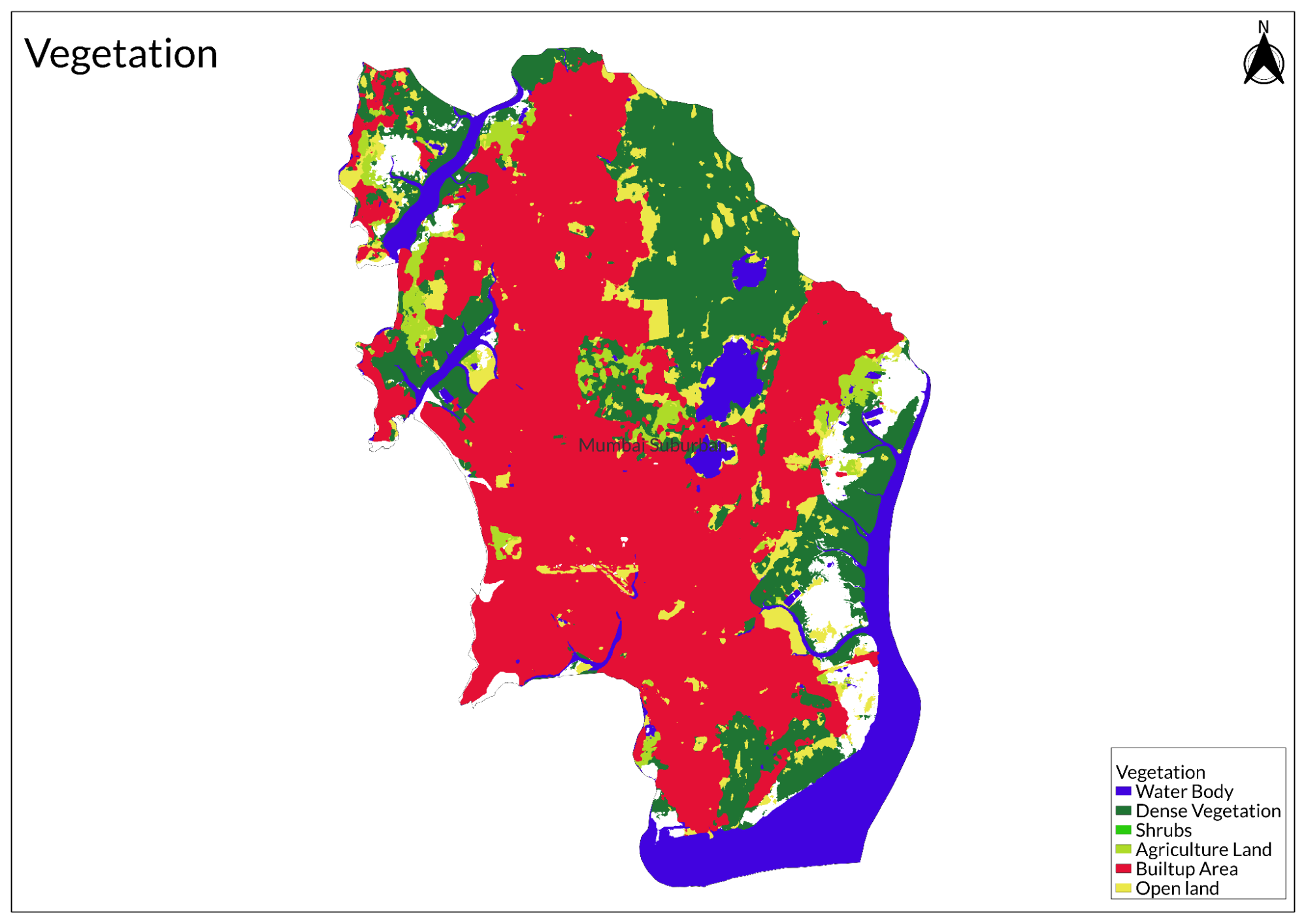

The district shows different soil types across areas. In Sanjay Gandhi National Park and Aarey, the soils support 1,300 plant species, including teak and kakad trees. The coastal areas have saline soils shaped by tides, supporting mangroves. Urban growth has changed soil conditions. Construction and drainage changes have altered soil profiles, as seen in Mulund Colony. Water affects soil formation through monsoons and tides, creating ongoing changes in soil structure. Some areas keep the soil good for farming, mainly in tribal settlements. Farmers grow rice, banana, and jackfruit, showing that fertile soil remains within urban areas.

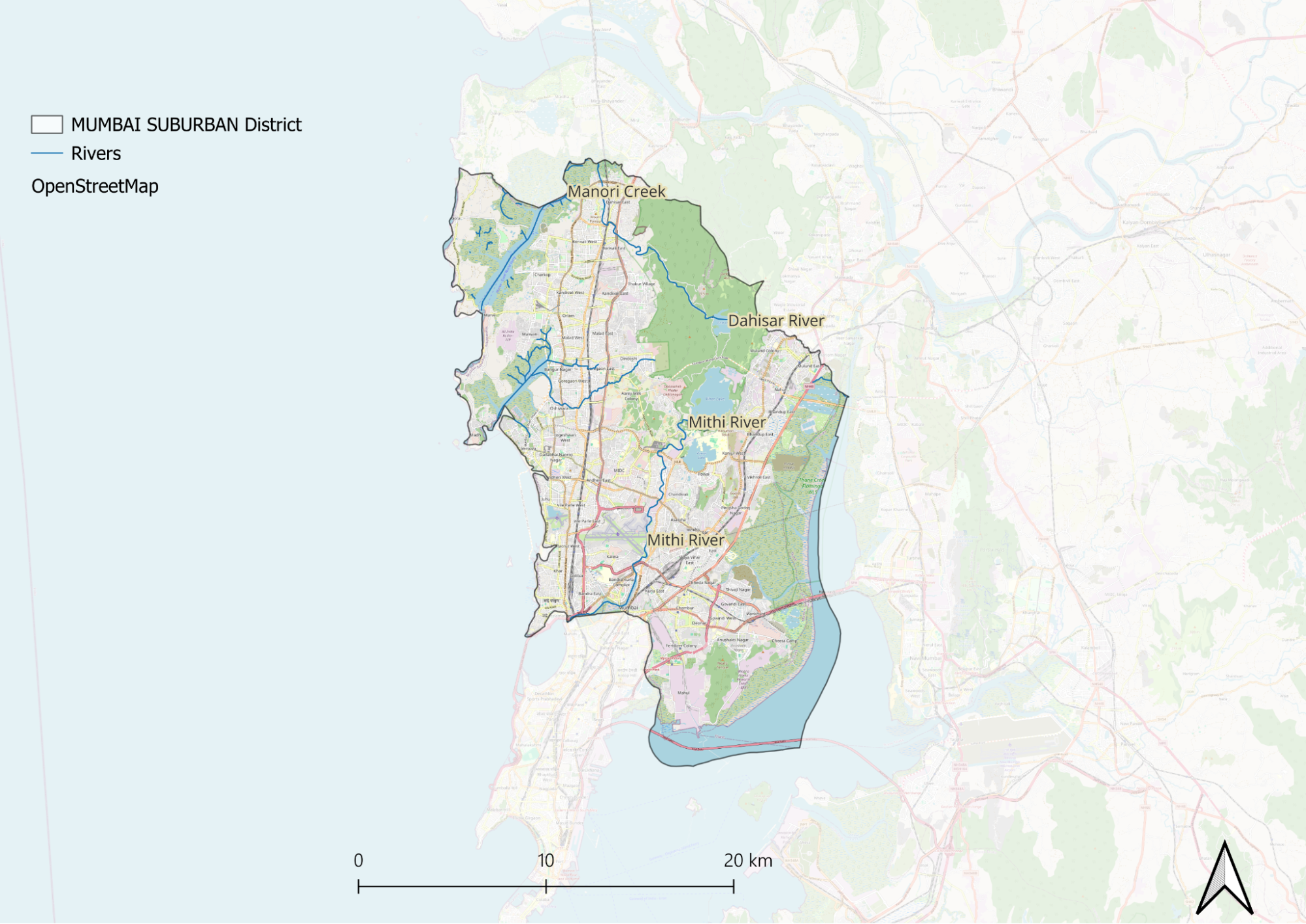

Rivers

The district contains four major rivers: the Mithi, Dahisar, Oshiwara, and Poisar. These rivers flow through the urban landscape before emptying into the Arabian Sea through different creek systems - the Malad, Mahim, Marve, and Thane creeks.

Second-generation partition refugees in the area of Mulund Colony recall that this nallah was once a channel where fresh clean water would flow. With concretization, this stream got turned into a nallah. The morphing of the nallah is estimated to be around the late 1970s or 80s. The source of the water cannot be ascertained as the landscape of the region has significantly changed over the years, but two important water-related sources reside near this stream. The first, being the Vihar Lake, and the second being a fresh-water drinking system that was established by the British, that lies within the nearby mountains.

Mumbai Suburban's four main rivers - Dahisar, Mithi, Oshiwara, and Poisar - flow into the Arabian Sea through the Malad, Mahim, Marve, and Thane creeks. Once vital waterways, these rivers have deteriorated significantly due to urban development and environmental neglect. Their current state, where they're commonly referred to as nullahs (drains), reflects the broader degradation of Mumbai's water ecosystems.

The Mithi River particularly illustrates these challenges. It gained public attention after the devastating floods of 2005, when its overflow inundated low-lying areas. In July 2019, similar flooding occurred when the river exceeded its danger mark, disrupting train services and forcing evacuations in Kurla, Sion, Bandra, and Powai. Despite ongoing protests and advocacy for its cleanup, the river continues to face serious pollution and flooding issues.

Other rivers show similar deterioration. The Oshiwara has shrunk to a narrow stream in many areas due to encroachment and construction along its banks. The Dahisar and Mithi rivers have become shallow from accumulated silt, debris, and plastic. During summer, the Dahisar's water levels drop drastically, concentrating pollutants.

These changes have severely impacted the region's natural drainage capacity. The transformation of these water bodies from rivers to drains has made the surrounding areas more vulnerable to flooding and environmental hazards, affecting thousands of residents who live along these waterways.

Flora and Fauna

The Mumbai Suburban district, rooted in the historical island of Salsette, was originally a collection of 66 villages known as Shahashasti, spanning from Khar, Dahisar, Mulund, Borivali to Thane. Over the years, Salsette has been fragmented into various divisions. Nevertheless, the Sanjay Gandhi National Park (SGNP), which partly lies within Mumbai's suburban district and partly within the outskirts of Thane district, serves as a testament to the island's geographical history and connection. The origins of the National Park are a little obscure. Some of its reserve forests were once part of the Maratha regime's property in the 19th century. The forest departmen,t established in the 19th century, oversaw the extraction of timber, poles, and teak from forest catchments near Vihar and Tulsi lakes under a fee known as ‘Vanmakta.’ [2]

SGNP stands as one of Maharashtra's six national parks, its importance to the region is immense. As their official website states, the park is “home to more than 254 species of birds, 40 species of mammals, 78 species of reptiles and amphibians, 150 species of butterflies, and over a staggering 1,300 species of plants.”

Beyond its primate population, SGNP harbors an impressive variety of wildlife. The park is notable for its large mammalian predators, including the endangered Panthera Tigris, Tiger (the park currently has around seven to eight tigers, the 2005 Flora of SGNP report details that after the shooting of the last tiger in 1925, the species could not be seen anymore within the periphery) and the majestic Panthera Pardus, the leopard, known as the largest predator in the area.

When it comes to the flora, the forest can be categorized into the categories of deciduous forest, teak-bearing forest, and semi-evergreen forests. The popular species that can be found within the forests are Teak, Sagwan, Kakad tree, Bahava, and so many more. The flora of SGNP has been extensively studied by both colonial and Indian botanists. As Mayur Nandikar states, the researchers have documented approximately 1300 flowering plant species across an area of 104 square kilometers. Among these, over 130 species are endemic to India. Saraca ashoka, also known as Sita ashok, is a rare and endemic tree species within the National Park.

Cultural Connections With Nature

Aghera

Aghera, an age-old festival celebrated by the East Indian community, is a significant event marked on the first Sunday of October each year. The festival takes place in 15-17 Gaothans (traditional East Indian villages) across the suburban region such as the Manori village, Gorai, and other such regions. One sheet of paddy, mostly sourced from Gorai, is traditionally distributed after the mass. This distribution holds cultural importance and may symbolize sharing the bounty of the harvest or community unity. This custom of harvest is symbolic of the community's agricultural roots and traditions.

Waghoba

Who would have thought that in a city like Mumbai, interesting tales of human-leopard coexistence would persist? There are plenty of shrines present in the forests of Aarey and SGNP (Borivali) which are revered by the adivasi community as the Tiger God, “Waghoba.” Waghoba is revered by the inhabitants as their divine protector who safeguards the people from the dangers lurking in the forest. Living harmoniously within the forest's embrace, tribal life revolves around a deep reverence for nature.

Leopards have inhabited SGNP for a significant period, adapting to the urbanizing environment as Mumbai expands northward. Despite being large carnivores, they have found ways to navigate this human-dominated landscape. The following article lists the tales of leopards named Adarsh Nagar, Bindu, Chandani and Luna, commonly seen during the period, who have their own interesting stories when it comes to their names and their encounters with the humans around.

Land Use

Environmental Concerns

Loss of Mangroves

Once teeming with marine life, the waters near Versova have suffered severe ecological decline due to pollution, habitat destruction, and climate change. Fishermen like Bhagwan Namdev Bhanji, who recall an era of clear waters and abundant fish, now struggle to sustain their livelihoods as untreated sewage and industrial waste choke Malad Creek, depleting oxygen levels essential for marine survival. The destruction of mangroves—key breeding grounds for fish—due to urban expansion has further diminished fish populations while increasing coastal erosion and storm vulnerability. Between 1990 and 2001 alone, Mumbai lost approximately 36.54 square kilometer of mangrove forests, accelerating the decline. Bhagwan laments, "The fish used to come to the coast to lay their eggs in the mangroves, but that cannot happen now." As a result, fishermen are forced to venture deeper into the sea, facing rising operational costs and greater risks, while unpredictable catches make their livelihoods increasingly precarious.

Climate change has exacerbated these challenges, with rising sea temperatures altering fish behavior and reducing mature fish sizes, as noted by Dr. Vinay Deshmukh of the Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute. Fishermen now catch smaller fish, leading to lower profits despite increasing market prices. Additionally, sea levels along the Indian coast have risen by approximately 8.5 cm over the past 50 years, making fishing communities like Versova Koliwada more vulnerable to storms. Frequent heavy rainfall and land reclamation practices have further intensified the impact, as seen in August 2019 when high tides damaged or destroyed several boats. With deep-sea fishing becoming economically unviable and coastal waters continuing to degrade, the future of Versova’s fishing communities remains uncertain.

Air Pollution

Mumbai's suburban areas are experiencing significantly worse air quality than the island city, as highlighted in the BMC's 2022-23 Environment Status Report. Monitoring stations in Andheri and Wadala recorded alarming PM10 levels, averaging 137 µg/m³ and 125 µg/m³, respectively—both exceeding the CPCB's limit of 100 µg/m³, with Andheri peaking at 290 µg/m³ in February 2023. PM2.5 levels also remained high, averaging 52 µg/m³ in Andheri and 50 µg/m³ in Wadala, surpassing safe limits, with Andheri hitting a peak of 123 µg/m³ in March. Experts link this disparity to lower wind speeds in the suburbs, which hinder pollution dispersion, along with local contributors like construction and waste burning. However, air quality improved during monsoon months (June-September), as rain helped wash away pollutants.

Water Pollution

Mumbai’s water bodies, once vital components of the city's ecosystem, have suffered significant degradation due to urbanization and neglect. The transformation of streams into polluted nullahs is evident in places like Mulund Colony, where second-generation partition refugees recall a time when fresh, clean water flowed through what is now a concretized drain. While the source of this water remains uncertain due to drastic landscape changes, two key water sources nearby—Vihar Lake and a British-era freshwater drinking system in the mountains—suggest its historical importance. This pattern is not unique; Mumbai's four rivers—Dahisar, Mithi, Oshiwara, and Poisar—once flowed naturally into the Arabian Sea but are now commonly referred to as nullahs, reflecting society’s casual disregard for their environmental deterioration. The shrinking of these rivers has not only led to pollution but has also exacerbated flood risks in suburban areas.

The Mithi River, in particular, has become synonymous with urban flooding and pollution. It was a major factor in the catastrophic 2005 Mumbai floods when it overflowed and submerged vast areas. In July 2019, after heavy rains, the river once again crossed its danger mark, flooding roads, halting suburban train services, and forcing evacuations in low-lying areas like Kurla, Sion, Bandra, and Powai. Similarly, the Oshiwara River has been reduced to a narrow, encroached stream, losing its natural drainage capacity and increasing the likelihood of urban floods. Dahisar, Mithi, and Oshiwara rivers have also suffered from severe silt accumulation, debris, and plastic waste, making them more shallow and incapable of handling excess rainwater. In the summer, the Dahisar River often dries up entirely, further concentrating pollutants. These deteriorating water bodies highlight the urgent need for conservation efforts to restore Mumbai’s natural drainage systems and reduce environmental vulnerabilities.

Effects of Climate Change

Coastal cities, historically hubs of growth and development, are increasingly vulnerable to climate change, particularly with rising global temperatures. Mumbai faces significant risks from sea level rise and intensified flooding, with projections suggesting that by 2070, over 1 crore 10 lakh residents will be living in high-risk areas—almost four times the current exposure. This growing threat raises serious concerns about housing, livelihoods, and overall well-being. According to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), sea levels have been rising at an alarming rate of 4.5 mm per year from 2013 to 2022, more than three times the rate recorded between 1901 and 1971. This acceleration is primarily driven by thermal expansion due to ocean warming (50%), melting glaciers (22%), ice sheet loss (20%), and land-water storage changes (8%).

Mumbai's geography amplifies its climate vulnerability. Originally a collection of seven islands, the city has been shaped by extensive land reclamation, leaving many areas below high water levels and highly susceptible to flooding, especially during heavy rainfall combined with high tides. Unchecked urban development and deforestation further worsen these challenges. Activists like Pamela Cheema from AGNI warn that projects such as the coastal road development are shortsighted, as rising sea levels may eventually submerge them. She emphasizes the importance of protecting green spaces like Sanjay Gandhi National Park and Aarey Forest, which act as natural barriers by absorbing excess rainfall and reducing flood risks.

Recent policy decisions, such as the approval of the Coastal Zone Management Plan (CZMP), have sparked concerns about further construction along Mumbai’s coastline. The plan allows for a higher Floor Space Index (FSI) near the seafront, raising fears that unchecked development could bring buildings dangerously close to the water's edge despite the increasing frequency of extreme weather events. Climate experts like Roxy Mathew Koll advocate for a more proactive approach, including early warning systems, improved drainage infrastructure, and community-led resilience initiatives. With Mumbai’s population expected to double by 2050, sustainable urban planning must prioritize long-term climate preparedness, such as flood maps based on projections for 2070-2100, to mitigate future disasters.

Conservation Efforts/Protests

Aarey Forests

Nestled in Goregaon, Aarey Forests stand as a stark contrast to the ever-expanding urban sprawl of Mumbai. Aptly called the “green lungs of Mumbai,” this lush forest is home to over 10,000 Adivasis across 27 tribal hamlets. Indigenous communities such as the Warli, Kokna, Mallar Koli, and Katkari continue to preserve their traditional way of life, sustaining themselves through poultry farming, goat rearing, and cultivating crops like rice, banana, jackfruit, guava, and paddy.

However, rapid urbanization and government projects have chipped away at Aarey's forested land. Plans for a milk colony, Film City, graveyards, zoos, and residential developments have continuously threatened its existence. The most significant controversy arose in 2014 when the Mumbai Metro Rail Corporation Limited (MMRCL) proposed constructing a metro car shed in Aarey, near a tribal hamlet called Prajapurpada. The project required clearing approximately 75 acres of land and cutting 2,298 trees. This led to a wave of protests, initially spearheaded by Adivasi women, who filed objections with the Tree Authority and even pursued legal action through public interest litigations.

Dubbed the largest forest conservation movement since the Chipko Andolan, the Save Aarey movement emerged as a response to the constant destruction of the forest. As construction projects encroached on wildlife habitats, leopards were forced out of the forest, seeking shelter beneath pipelines and sewers. Meanwhile, Adivasis, who had lived sustainably in Aarey for generations, faced displacement and land disputes under the guise of "development," even as basic amenities like electricity remained inaccessible in their homes.

Several organizations united to protect Aarey’s ecological and cultural heritage. The Aarey Conservation Group, a coalition of multiple environmental NGOs like Vanashakti and AGNI, led protests and awareness campaigns. Vanashakti actively pursued legal battles, filing petitions to declare Aarey a reserved forest and eco-sensitive zone. Youth For Aarey, founded by Aparna Bangia and Sukriti Gupta, engaged young activists through biodiversity walks and protests. The Adivasi Hakk Sanvardhan Samiti, led by Prakash Bhoir, focused on tribal rights, addressing issues related to land, infrastructure, and environmental conservation. Additionally, the Waghoba Habitat Foundation, founded by activist Sanjiv Valsan, promoted conservation, sustainability, and indigenous ecology through afforestation drives, eco-tourism, and community engagement.

Art played a crucial role in the protests, serving as a medium of resistance and cultural assertion. Warli art was reimagined to depict the struggle for Aarey, while rap music became a tool for raising awareness. Even festivals took on new meaning—during Raksha Bandhan, activists and tribals participated in Vrikshabandhan, a symbolic event where they tied rakhis to trees facing destruction from various developmental projects.

Despite years of protests, legal battles, and widespread public support, construction of the metro car shed in Aarey has continued, underscoring the complexities of urban environmental activism.

Environmental NGOS

Bombay Environmental Action Group

The Bombay Environmental Action Group (BEAG), founded in 1979, has been a pioneer in environmental conservation through policy advocacy and litigation. Their work encompasses urban planning, heritage conservation, and the protection of eco-sensitive areas, making them a key player in Mumbai's environmental landscape.

NAGAR

NAGAR, established in 2000, addresses various urban environmental challenges such as solid waste management and air pollution. They advocate for improved governance policies and engage in public awareness campaigns to foster community involvement in...

The Navi Mumbai Environment Preservation Society (NMEPS)

The Navi Mumbai Environment Preservation Society (NMEPS) is dedicated to the conservation of mangroves, lakes, and wetlands in the region. Through environmental advocacy, wildlife protection, and community education, NMEPS collaborates with local communities to promote sustainable practices and habitat preservation. Their efforts include organizing awareness campaigns and engaging residents in conservation activities.

Vanashakti

Vanashakti, established in 2006, focuses on the conservation of forests, mangroves, and wetlands. The organization emphasizes environmental education, legal advocacy, and sustainable livelihood programs for communities dependent on these ecosystems....

Waghoba Habitat Foundation

Waghoba Habitat Foundation is a non-profit organization that promotes habitat conservation by integrating indigenous knowledge with climate action. They focus on fostering a harmonious relationship between humans and nature through community engagement and rewilding projects.

Graphs

Water

Climate & Atmosphere

Forests & Ecology

Human Footprint

Sources

Aarey Conservation Group. https://aareyconservationgroup.org/

Anthony, H. 2023, December 27. Nine years of “Save Aarey”: The unique citizens’ movement lives on in Mumbai. Citizen Matters.https://citizenmatters.in/mumbai-aarey-movem…

Bhadgaonkar, K. B., Jai. 2022, September 5.The ‘forgotten’ water ecosystems of Mumbai. Down To Earth.https://www.downtoearth.org.in/environment/t…

Chandramouli, K. 2018, November 16.The leopards of aarey. Mongabay-India.https://india.mongabay.com/2018/11/the-leopa…

Jiwani, S. The shrinking pomfret of suburban Mumbai. UNDP India; United Nations.https://www.undp.org/india/shrinking-pomfret…

Mumbai’s Mithi river woes: Unkept promises lie buried under poll noise. 2024, May 19. The Economic Times.https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/el…

Nandikar, M. 2018, September. Endemic Flora of Sanjay Gandhi National Park (SGNP), Mumbai.Vanshobha.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327…

Tandon, K. C. & A. 2018, November 19. ‘Who will protect Waghoba?’ Mumbai metro project threatens to drive away leopards from Aarey. Scroll.In.https://scroll.in/article/902390/who-will-pr…

Tying rakhis to trees in Aarey colony. 2020, August 3. [Youtube Video]. Citizens for Justice and Peace.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=08jdkkafzoc

Unique Highlights. Sanjay Gandhi National Park (SGNP); Government of Maharashtra.

Vanashakti.https://vanashakti.org/

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.