Contents

- Crop Cultivation

- Agricultural Communities

- Festivals or Rituals Related to Farming

- Types of Farming

- Orange Cultivation

- Climate Change’s Effects on Oranges

- Traditional Agricultural Practices

- Use of Technology

- Changes in Cropping Pattern

- Institutional Infrastructure

- ICAR-Central Citrus Research Institute, Nagpur

- Market Structure: APMCs

- List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

- Farmers Issues

- Climate Change and Its Impact on Agriculture in Nagpur

- Awareness about Schemes

- Graphs

- Irrigation

- A. No. of Projects

- B. No. of Ponds/Vilage Lakes and Storage Dams

- C. Irrigation Beneficiary Area vs Irrigated Area

- D. Share of Beneficiary Area Irrigated

- E. Tubewells and Pumps Installed In The Year

- F. Irrigation and Water Pumping Facilities

- Cropping Metrics

- A. Share in Total Holdings

- B. Cultivated Area (With Components)

- C. Gross Cropped Area (Irrigated + Unirrigated)

- D. Share of Cropped Area Irrigated

- E. Distribution of Chemical Fertilizers

- Land Use and Credit

- A. Area of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- B. Size Groups' Share in Total Agricultural Land Holdings Area

- C. No. of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- D. Size Groups' Share in Total No. of Agricultural Land Holdings

- E. Agricultural Lending

- F. Agricultural Credit as a share of Total Credit

- Sources

NAGPUR

Agriculture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

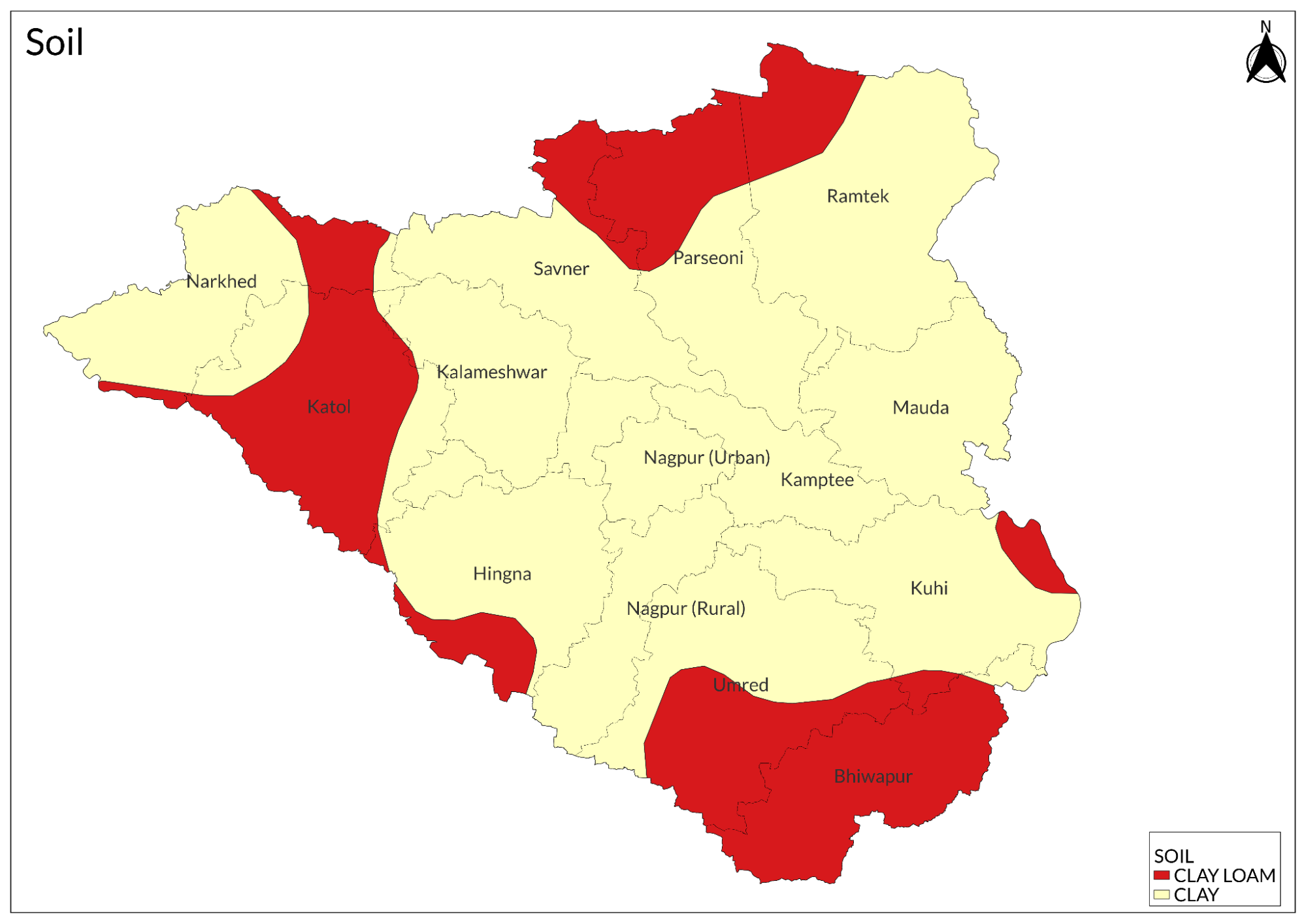

The district of Nagpur is situated in the drought-prone Vidarbha region of Maharashtra, in the Central Highlands, and has a Hot, sub-humid climate. Known for its shallow to deep Black soil. The district heavily relies on agriculture, with Cotton and Soybean as the major crops. Notably, Nagpur city has a famous sobriquet associated with it, the Orange City of India, due to the enormous Orange cultivation in the district. The district is drained by rivers such as Kolar, Nag, Wainganga, Maru, Pora, Pench, Wardha, Kanhan, etc.

Crop Cultivation

Nagpur's topography consists of plateau regions, moderate hills, and fertile plains, which considerably impact the area's agriculture operations. The district's soil is divided into three categories: black soil, alluvial soil, and laterite soil. Soybeans, cotton, and wheat are the most common crops cultivated in deep black soil. These soils are highly fertile, allowing for large yields.

Nagpur’s agricultural landscape has remained consistent over the years, with the Imperial gazetteer describing the main crops during the 19th century to be santri (orange), kagadi nimbu (lime), and Italian lemon. Today, these staples, along with hat or dhan (rice), continue to be cultivated in the district. In addition to this, Nagpur is a district that also produces pulses, oilseeds, spices, fruits, vegetables, and fodder crops.

Nagpur's horticulture produces a wide range of fruits and vegetables, contributing significantly to the region's agricultural landscape. It is best known for its orange production, which has earned it the nickname "Orange City." Other fruits and vegetables include Kele (banana), Amba (mango), Peru (guava), papaya, Kalingad (watermelon), Ratale (sweet potato), Kanda (onion), etc. Crops such as Bhiwapur Chilli and Nagpur Oranges have also received GI tags from the government.

Agricultural Communities

According to the Central Provinces District Gazetteers of 1908, various communities in the district are linked to agriculture. The Deshasth Brahmins are noted as scientific agriculturists, while the Marathas, a community historically connected to Shivaji Maharaj's guerrilla warfare against Aurangzeb and other local rulers, are also involved in farming. Many Marathas transitioned from being warriors to landholders (zamindars) and farmers after the decline of the Maratha Empire. They controlled large swaths of land and became prominent agriculturists. Over time, their focus shifted from military activities to the agrarian economy, and many have continued to be influential in rural agriculture and politics.

The Kunbis are described as the most prominent agricultural community. Additionally, the Kiraris, Lodhis, and Raghvis are immigrant cultivator communities that migrated from Madhya Pradesh to the region. Lodhis are a well-known agrarian community, not only in Maharashtra but also in parts of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. They are traditionally farmers, and their migration to Maharashtra allowed them to apply their agricultural knowledge to new lands.

The Mahars, who traditionally provided agricultural labor, now play a significant role in the rural economy. Over time, and especially with the influence of social reform movements led by leaders like Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, many Mahars were able to acquire land. This marked a significant shift in their socio-economic status, as they transitioned from laborers to landowners and cultivators. They are now involved in farming their land, often cultivating small to medium-sized plots.

Lastly, the Gonds stand out as one of the region's most historically and ethnologically significant indigenous communities. Once the dominant group in the district and its surroundings, the Gonds' presence has shaped the cultural and social landscape for centuries. Today, they are divided into four distinct endogamous groups: the Raj-Gonds, Madia, Dhurve, and Khatulwar Gonds. The mahua tree, in particular, holds great value for these communities. Its flowers are picked up each year, not just for food but as a key economic resource.

Festivals or Rituals Related to Farming

Every year, during August and September, the city of Nagpur in Maharashtra celebrates a 143-year-old event in which enormous effigies representing evil are paraded through the streets to the accompaniment of loud music, dancing, and chanting before being burned.

The Marbat event is held on 'Tanha Pola', the day after Pola, when residents in rural Maharashtra and Chhattisgarh thank their bulls for their contributions to farming efforts. Gigantic female effigies, known as Marbat, roam the narrow streets of Nagpur's ancient city, from their creation locations to Nehru Putla Square.

The Kali (black) Marbat awaits while hundreds of revelers chant, "Ida pida gheun jaa ge Marbat (Take away all evil and go, Marbat)."Rog rai gheun jaa ge Marbat (Remove all diseases and go, Marbat).

Types of Farming

Orange Cultivation

Nagpur is famously known as the "Orange City," with a strong emphasis on orange farming. Other fruits, including bananas and guavas, are also farmed. The origins of Nagpur’s citrus legacy may be found in the 18th century, during the Bhonsle’s control of the city. The Bhonsles promoted orange farming, creating the groundwork for a citrus empire. These kings vigorously encouraged orange farming after realizing Nagpur’s soil had potential for it. As a result, Nagpur started to become known as a center for the production of citrus.

Nagpur orange was successfully tried as a kitchen garden plant for the first time by the Late Shri Raghujiraje Bhonsle in 1896. Since that time, orange production has grown steadily each year, becoming one of the most lucrative prospective foreign exchange-earning crops in this area. After mango and banana, Nagpur oranges are one of the national horticultural crops.

Nagpur oranges blossom throughout the monsoon season and are ready for harvest in December. The orange crop grows twice a year. A medium, 2 1/2-inch orange contains a lot of vitamins, minerals, and fiber.

Nagpur oranges flower during the monsoon season and are ready for harvest. The orange crop increases twice per year. Ambiya, a slightly sour-tasting fruit, is available from September to December. It is succeeded by the sweeter Mrig crop in January. Normally, farmers choose either of the two types. Nagpur Orange also received a GI tag in 2014.

Despite the advantages, orange farmers frequently encounter fluctuating market conditions. For example, a surplus in production can lead to dramatic price declines, with reports estimating prices falling to as low as Rs. 4-5 per kg during oversupply situations. The spread of orange farming to other locations, including Rajasthan, has increased competition for Nagpur oranges. Farmers also face natural calamities, which can have an impact on crop output and quality. While various initiatives have been initiated, such as juice production plans from companies like Patanjali Ayurved, many past attempts to develop a profitable processing industry have failed.

Climate Change’s Effects on Oranges

In recent years, several factors, ranging from environmental changes to financial and logistical difficulties, have adversely impacted the sustainability of orange cultivation in the region. Farmers, who rely heavily on this crop for their income, are grappling with a multitude of issues that put their production and profits at risk.

Heatwaves, especially when they coincide with crucial stages of fruit development, can cause "fruit drop," where the oranges fall prematurely before ripening. In some cases, prolonged exposure to extreme heat can lead to the complete loss of crops, a devastating outcome for farmers whose income depends on a successful harvest.

High temperatures and heat waves, cloudy skies, unexpected rains, and irregular seasons affect the timing of flowering and fruiting. Extreme weather events like sudden heavy rainfall cause soil erosion, waterlogging, and nutrient leaching, weakening orange trees that thrive in warm, tropical climates. The trees become more vulnerable to pests, increasing the farmers’ need for expensive chemical treatments, which add to their financial burden.

Citrus crops are sensitive to both excessive rainfall and drought, making them more susceptible to diseases such as "root rot" and "mildew," which can destroy entire orchards. New pests, such as the Citrus psylla (Diaphorina citri), have become a major threat to orange crops. This pest spreads a bacterial disease called "citrus greening" (Huanglongbing, or HLB), which causes the fruit to become misshapen, bitter, and unmarketable.

Traditional Agricultural Practices

In Nagpur district, all cultivable land falls into one of three categories: jirayat (dry cropland), bagayat (watered or garden land), and bhat lands. Dry crop areas are further separated into kharif (early monsoon) and rabi (late monsoon).

The Kharif season, which begins in the middle of June and ends in the middle of October, is mostly characterised by rainfall from the southwest monsoons and occasional antecedent monsoon showers in April-May and the first half of June. Cotton, jowar, paddy, groundnut, fur, kulthi, udid, mug, chavali, til, castor seed, ambadi chillis, brinjals, bhendi, cucurbits, and green vegetables are the district's primary kharif crops. The sowing operations for kharif crops begin in the middle of June and end in the middle of July. The sowing and reaping of these crops roughly coincide with the start and end of the monsoon. These crops are typically harvested between October and December. Except for paddy, the majority of Kharif crops are cultivated in Katol and Saoner tahsils, as well as the western parts of Nagpur and Ramtek tahsils. Paddy is widely grown in the eastern regions of Ramtek and Umrer tahsils.

The rabi season begins in the middle of October and ends in the middle of February. Rabi crops are more essential in the district's centre region, which includes the southern part of Ramtek tahsil, the eastern parts of Nagpur, and Umrer tahsils, where the southwest monsoons are few and unpredictable. It receives the majority of its rainfall from the northeast monsoon. On average, it measures 50.8 mm (2"). These rains, together with the moisture stored by the land during the kharif season, bring the rabi crops to maturity. Rabi crops are sown in October and November and mature between the end of January and March. Wheat, gram, jowar, linseed, lakeshore peas, val, garlic, sweet potato, onion, carrot, brinjals, chilies, and so on are the most common crops grown during the Rabi season.

The hot season is largely ignored by growers, thus it is unimportant. However, preliminary tillage is carried out in the latter stages.

The indigenous communities of Nagpur have a vast range of agricultural activities. The Bhunjias, for example, are well-known for their expertise in farming and animal husbandry. They practice established agriculture, growing crops such as cereals, legumes, and vegetables. They also raise livestock such as cattle, goats, and sheep for milk, meat, and wool.

The Gonds, on the other hand, use shifting cultivation, often known as slash-and-burn agriculture, as an important part of their agricultural techniques. This strategy entails burning forest areas and then producing crops on the cleared ground. And then cultivating crops like maize, millet, and rice. They also harvest forest produce such as fruits, nuts, and medicinal plants.

Use of Technology

Plows, harrows, levelers, clod crushers, seed drills, and hoes are the most popular tools used at different phases of agriculture. Aside from that other hand tools are used for a variety of chores around the farm. Field tools and implements, which have traditionally been old and indigenous, are being supplanted by more contemporary alternatives. Tractor-drawn plows and disc harrows are increasingly being used in large-scale farming. Pumps powered by electric motors and oil engines were recently installed in certain portions of the district.

Changes in Cropping Pattern

Cropping patterns have shifted significantly, with regions previously utilized for orange and cotton cultivation now being turned to non-cereal crops, mainly oilseeds. This transition is related to changing climate conditions that make it less feasible to farm these traditional crops.

Excessive rainfall during important growth stages raises the risk of fungal diseases and pests, compromising crop health. Waterlogged circumstances can cause root rot and nitrogen loss from the soil.

Institutional Infrastructure

According to the NABARD’s Potential Linked Credit Plan (PLP) report 2023-24, the district has a fairly good agricultural infrastructure, including 13 Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs), 80 godowns, 13 cold storage facilities, 74 plantation nurseries, 587 Primary Agriculture Credit Societies, 150 farmers' clubs, and approximately 1300 fertilizer, seed, and pesticide outlets. Additionally, there is one Krishi Vigyan Kendra (KVK) supporting agricultural extension services in the region.

ICAR-Central Citrus Research Institute, Nagpur

Located in Nagpur City, the Central Citrus Research Station under IIHR, Bengaluru, at Nagpur was formally inaugurated on 28th July 1985. To research different applied and fundamental aspects of citriculture, the status of Citrus Research Station was raised to the independent National Research Centre for Citrus (NRCC) in April, 1986. The NRC for Citrus was upgraded to the Institute level and renamed Central Citrus Research Institute (CCRI) in October 2014. Since then, ICAR-CCRI has been functioning, working on different problems of citriculture. The Institute has been working in various fields, especially those of Genetic Resources and Crop Improvement, Crop Resource Management, Disease and Pest Management, Plant Pathology, etc.

Market Structure: APMCs

The main market yard is located at Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru Market Yard in Kalamna, which covers around 110 acres. This facility consolidates several sub-markets that were previously dispersed throughout the city, including marketplaces for grains, fruits, vegetables, and livestock.

Nagpur, the winter capital of Maharashtra, is known as "Orange City" due to its role as a significant commercial center for the region's orange production. The district is the leading exporter of rice, followed by cotton and soybeans.

List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

|

Sr. No |

Name |

Est. Year |

Chairman |

No. of Godowns |

|

1 |

Bhiwapur |

1968 |

Balu Muralidharji Ingole |

6 |

|

2 |

Hingna |

2006 |

Balu Muralidharji Ingole |

2 |

|

3 |

Kalmeshwar |

1962 |

Babarao Kauduji Patil |

3 |

|

4 |

Kamthi |

2006 |

Aniket Purushottam Sahane |

NA |

|

5 |

Katol |

1940 |

Charnshing Babulalji Thakur |

6 |

|

6 |

Mandhal |

1972 |

Manoj Titarmare |

3 |

|

7 |

Mauda |

2014 |

Bapu Madhavji Kokate |

2 |

|

8 |

Nagpur |

1974 |

Ahmedbhai Karimbhai Shaikh |

3 |

|

9 |

Narkhed |

1969 |

Sureshrao Jagannathji Arghode |

3 |

|

10 |

Parshiwani |

1986 |

Ashok Balaji Chikhale |

2 |

|

11 |

Ramtek |

1973 |

NA |

NA |

|

12 |

Savner |

1973 |

Ravindra Manohar Chikhale Rupchand Ramkrushnaji Kadu |

NA |

|

13 |

Umner |

1974 |

Ravindra Manohar Chikhale Rupchand Ramkrushnaji Kadu |

7 |

Farmers Issues

Climate Change and Its Impact on Agriculture in Nagpur

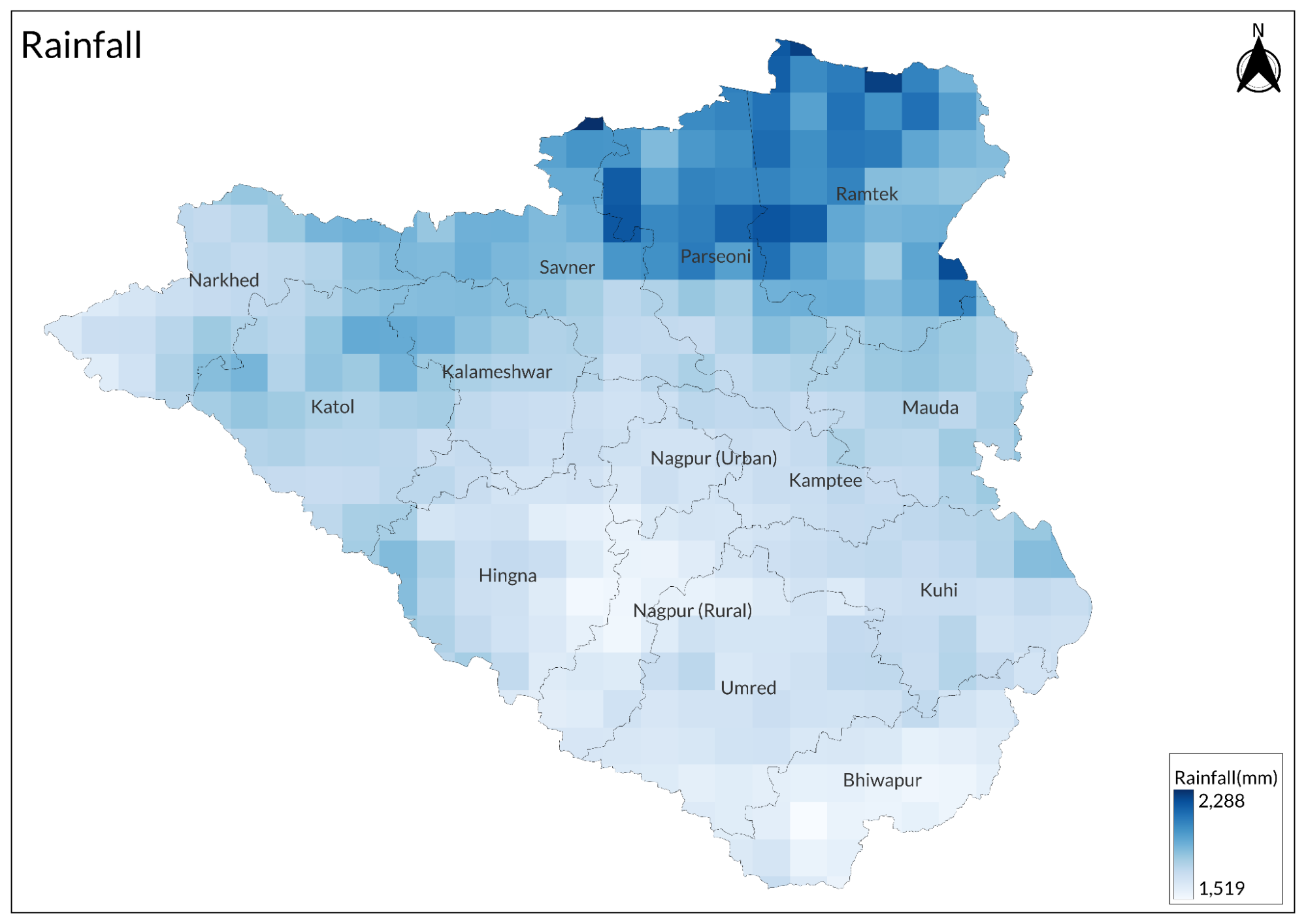

According to a newspaper article, in March 2024, district collector Vipin Itankar declared drought-like conditions in five revenue circles, which received 75% less rainfall than average. An officer from the collectorate stated that these five revenue circles cover around 30 communities. The affected areas were to receive all of the incentives available to tehsils classified as suffering from droughts.

This is believed to have been caused by the erratic rains of 2023. In June 2023, the monsoon was delayed by almost a fortnight. In July, there was a deluge caused by excessive rain, which harmed crops, and in August, there was a prolonged dry spell, which harmed crops. According to the district revenue department's observations, five of Nagpur district's 11 revenue circles received less than 75% of the average or less than 750mm of total rainfall between June and September 2023.

Awareness about Schemes

The Ambuja Foundation, an NGO, works on rural development in Maharashtra, especially agriculture. They work on a variety of activities, including water conservation, sustainable farming methods, and women's empowerment through self-help organizations. Their projects include building check dams, promoting micro-irrigation systems, and assisting farmers in adopting improved agricultural methods to increase productivity and lessen reliance on moneylenders.

RCONF, based in Nagpur, supports organic farming practices throughout several states, including Maharashtra. They concentrate on educating farmers about organic methods and facilitating the transition from conventional to organic farming, which can improve soil health and expand market prospects for farmers.

Graphs

Irrigation

Cropping Metrics

Land Use and Credit

Sources

Ambuja Foundation. NGO Maharashtra.https://www.ambujafoundation.org/ngo-maharas…

Ankita Deshkar. 2024. Marbat festival: Nagpur’s tryst with a century-old tradition of banishing ‘evil’. Indian Express.https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/mum…

Britannica Kids Editors. Gond. Britannica Kids.https://kids.britannica.com/students/article…

Directorate of Industries (Export Division), Industries Department, Govt. of Maharashtra. 2022. Maharashtra One District One Product (ODOP) Booklet. Industries Department Government of Maharashtra.https://maitri.mahaonline.gov.in/PDF/MHODOPB…

Jaideep Hardikar. 2024. Gondia's poor still bank on 3Ms: mahua, MNREGA, and migration. People’s Archive of Rural India, Gondiahttps://ruralindiaonline.org/en/articles/gon…

K. U. Deshmukh, G. R. Tidke, and M. K. Rathod. 2018. Impact of Climate Change on Developmental Parameters of Farmers. Special Issue. 07. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences.https://www.ijcmas.com/special/7/K.%20U.%20D…

M. Raghuram. 2024. DTE Ground Report: Human-induced climate change threatens Nagpur Oranges; can this heritage be saved? Down to Earth, Nagpur.

NABARD. 2023-24. Potential Linked Credit Plan: NAGPUR. Maharashtra Regional Office, Pune.

Nconf. Dac.gov.inhttps://nconf.dac.gov.in/regional/nagpur

Proshun Chakraborty. 2024. Drought-like conditions in 30 villages of Nagpur district. Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/nag…

R.V. Russell. 1908. Central Provinces District Gazetteers, Nagpur District. Times Press, Bombay.https://gazetteers.maharashtra.gov.in/cultur…

Shishir Arya. 2016. The Bitter Story of Nagpur Orange. Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/nag…

Universal Tribes Staff. 2023. Bhunjia Tribal community. Universal Tribes.https://universaltribes.com/blogs/news/bhunj…

Yash Lakhan. 2022. Why is Nagpur called Orange City? Slurphttps://www.slurrp.com/article/why-is-nagpur…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.