Contents

- Crop Cultivation

- Agricultural Communities

- Empowering Women in Agriculture

- Festivals/Rituals Related to Farming

- Gudi Padwa

- Types of Farming

- Slash-and-Burn Cultivation (JHUM/ JHOO)

- Sustainable Farming

- Traditional Agricultural Practices

- Use of Technology

- Institutional Infrastructure

- Market Structure: APMCs

- Farmers Issues

- Graphs

- Irrigation

- A. No. of Projects

- B. No. of Ponds/Vilage Lakes and Storage Dams

- C. Irrigation Beneficiary Area vs Irrigated Area

- D. Share of Beneficiary Area Irrigated

- E. Tubewells and Pumps Installed In The Year

- F. Irrigation and Water Pumping Facilities

- Cropping Metrics

- A. Share in Total Holdings

- B. Cultivated Area (With Components)

- C. Gross Cropped Area (Irrigated + Unirrigated)

- D. Share of Cropped Area Irrigated

- E. Distribution of Chemical Fertilizers

- Land Use and Credit

- A. Area of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- B. Size Groups' Share in Total Agricultural Land Holdings Area

- C. No. of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- D. Size Groups' Share in Total No. of Agricultural Land Holdings

- E. Agricultural Lending

- F. Agricultural Credit as a share of Total Credit

- Sources

PUNE

Agriculture

Last updated on 7 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Pune is experiencing a complex interplay of urban growth and agricultural persistence. On one hand, agricultural lands are being sold for real estate, causing farms to recede from the city. On the other hand, regions like Shirur, Ambegaon tehsil, and Kamshet continue to uphold agriculture as a vital source of livelihood, reflecting the resilience of traditional farming practices amid rapid urbanization.

Crop Cultivation

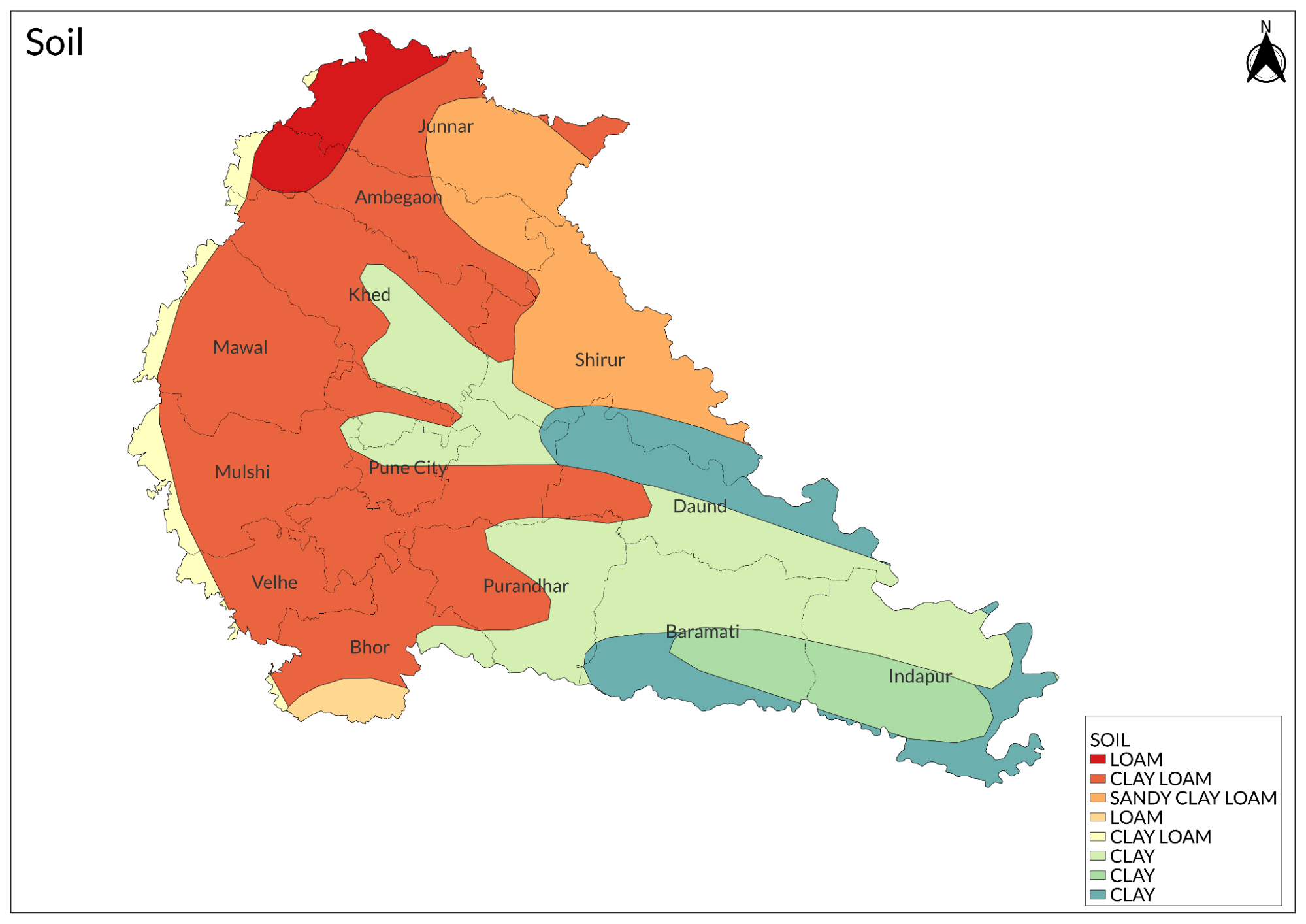

Pune district, nestled in western Maharashtra, was blessed with an abundance of rivers flowing from the Western Ghats, including the Mula, Mutha, Pawana, Ram, and Dev, which nurtured its rich agricultural landscape. Historically, the region was deeply rooted in agrarian practices, with a substantial portion of land dedicated to cultivation, as highlighted in the Pune Gazetteer. Grain crops formed the backbone of local agriculture, with jvari (Indian millet) and bajri (spiked millet) being particularly prominent. Other grains like gahu (wheat), nachni (ragi), and Bhat (rice) were also widely grown, alongside pulses such as harbhara (gram) and tur (pigeon pea), as well as oilseeds like til (gingelly seed), which collectively shaped the region's agricultural identity.

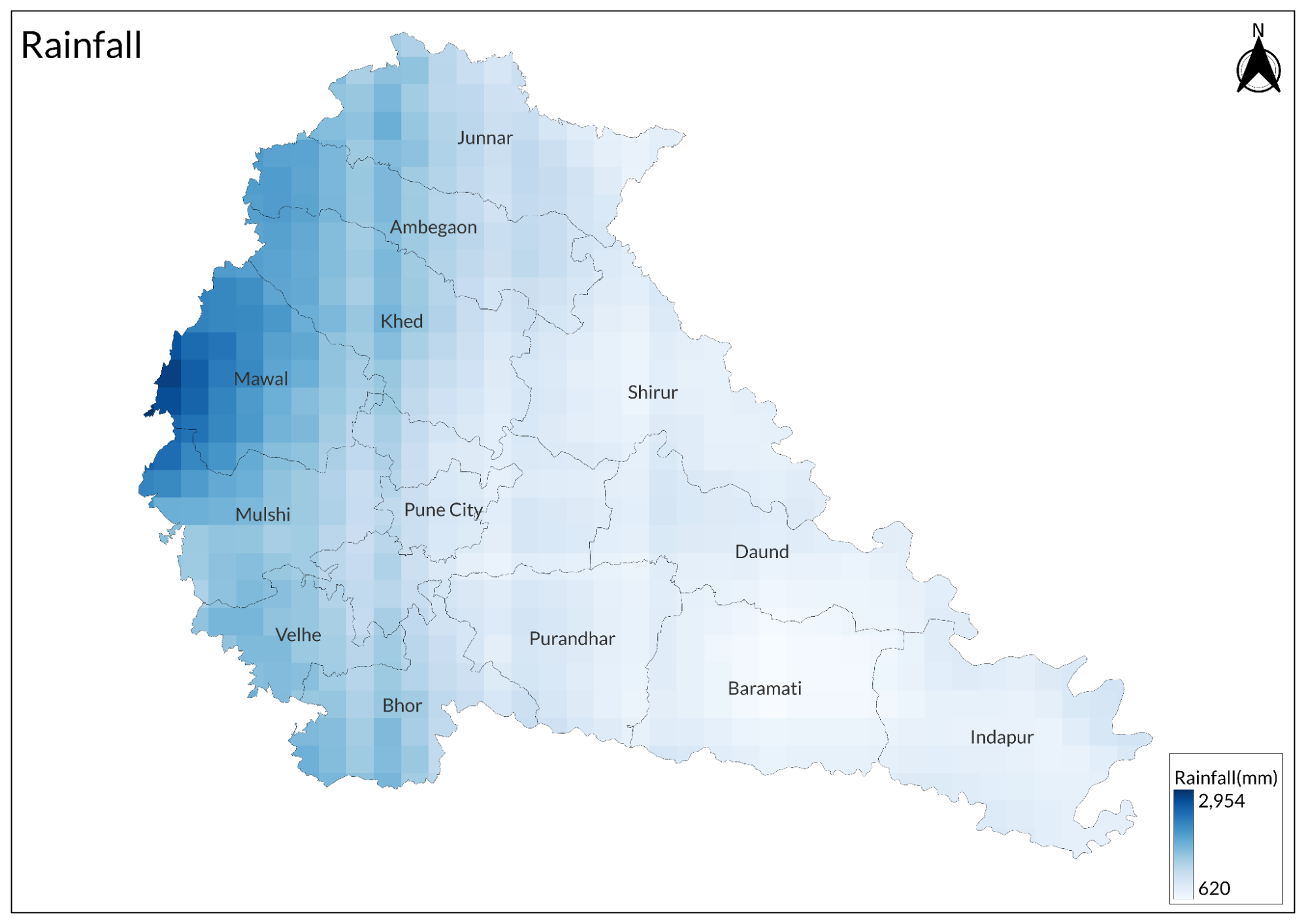

Today, this agricultural heritage remains vital, especially in the western talukas such as Mulshi, Bhor, and Velhe, which receive substantial rainfall and continue to support the cultivation of important crops like Sugarcane, bhat (rice), and jowar (sorghum). This ongoing reliance on diverse crop cultivation not only sustains local livelihoods but also contributes to the region’s food security and economic stability.

Moreover, the district is renowned for its fruit production, with kela (bananas) thriving in Junnar, and Baramati and Haveli being celebrated for their angoor (grapes). Purandar is particularly significant for its anar (pomegranates), anjeer (figs), and sitafal (custard apples), along with a unique variety of mirchi (chilies).

Among the local specialties, the Purandar variety of anjeer is especially significant. It gained a Geographical Indication (GI) tag in 2016, a recognition that underscores its unique qualities, traditional production methods, and the cultural heritage of the region. These figs are sought after in high-value export markets, including Hong Kong, Germany, the Netherlands, and the Middle East, thanks to the efforts of the Purandar Highlands Farmers Producers Company (PHFPC) and its Chairman, Rohan Ursal.

Interestingly, Pune also had a moment in the spotlight with coffee cultivation! The once-thriving coffee plantations in Mundhwa and Hadapsar, nestled in Haveli taluka, have sadly fallen victim to ownership disputes. It’s a missed opportunity, especially since the coffee produced there earned rave reviews from the Europeans in the Cantonment area. Two enterprising Anglo-Indians, William Sundt and William Webbe, transformed the landscapes of Mudhwa and Hadapsar into flourishing gardens.

Their coffee adventure kicked off in 1839, and the Bombay Chamber of Commerce praised it for its outstanding quality and cleanliness, noting it could fetch prices akin to the finest Mocha coffee. To encourage their ambitious project, the government even gifted them ten acres of land adjacent to their gardens. According to Sundt, the red gravelly soil was a perfect match for coffee cultivation, making it a fascinating chapter in Pune's agricultural history.

Agricultural Communities

Pune district's agricultural landscape has historically been shaped by its farming communities, each contributing uniquely to the region’s farming practices. The primary cultivators include the Kunbis and Malis, but the agricultural scene is far more diverse. Land ownership spans various groups such as Brahmans, Gujar Marwar, Lingayat Vanis, Dhangars, Nhavis, Kolis, Ramoshis, Mhars, Chambhars, and Musalmans.

A notable aspect, which the Gazetteer highlights (1885), is that about four-fifths of landholders cultivate their fields, reflecting a deep connection to the land. The Kunbis, in particular, rely almost entirely on their agricultural produce for their livelihoods. Meanwhile, many Dhangars engage in both farming and livestock rearing, along with weaving blankets, showcasing a blend of agricultural and artisanal skills.

However, farming in the Pune district is not without its challenges. The erratic rainfall, the variability in soil quality, and limited crop diversity have historically contributed to the economic struggles of these communities. Many farmers have faced the burdens of debt, often exacerbated by unwise dealings with moneylenders. During British rule, revised land assessment rates between 1863 and 1868 further impacted their financial stability, leaving many in precarious situations.

Today, it is said that the Kunbis and Malis remain closely connected to their agricultural roots, while other communities have been increasingly moving away from traditional farming practices. This shift reflects broader changes in lifestyle and economy.

Empowering Women in Agriculture

Innovative projects are emerging to empower women in farming. In Narayangaon, Junnar taluka, the social startup BeePositive, led by Kanupriya, has trained women farmers in beekeeping, creating profitable ventures through the MadhuShakti project. The honey produced has achieved impressive sales via Self Help Groups (SHGs), granting financial independence to many participants.

Another inspiring story of a successful woman agripreneur is Anjali Waman from Junnar taluka in the Pune district. While most farmers in her area primarily practice monoculture and rely heavily on market fluctuations for their annual harvests, Mrs. Waman took a bold step in a different direction. With support from the local Krishi Vigyan Kendra (KVK) in Narayangaon, she established a nutrition garden right in her backyard, cultivating a vibrant mix of 25 different vegetables and 4 varieties of fruit seedlings.

Her hard work quickly paid off, and she began selling her organic produce at local markets. The success of her nutrition garden inspired her to expand further, and soon her village of Kalwadi took notice. Over 100 women began to follow her innovative approach, turning the concept of the nutrition garden into a community-wide movement. This initiative, dubbed the Waman Model or Poshan Vatika, has not only enriched local diets but also empowered women in the area to pursue sustainable farming practices and achieve financial independence.

Pune is actively fostering a diverse range of agricultural practices that are having a ripple effect across various districts in Maharashtra. The region's agricultural landscape is evolving through innovative approaches, sustainable methods, and community-driven initiatives that not only enhance productivity but also promote environmental stewardship.

One notable organization leading this charge is Swayam Shikshan Prayog, a Pune-based startup founded by the late Prema Gopalan and Sheela Patel. This organization advocates for water conservation and encourages the cultivation of crops suited to local agro-climatic zones. By assisting women farmers in transitioning from water-intensive crops like sugarcane and cotton to more eco-friendly alternatives, Swayam Shikshan Prayog is not only promoting sustainability but also empowering women to take charge of their agricultural practices. Their work includes designing water-efficient models that avoid harmful chemicals and fertilizers, as well as fostering crop diversification and increasing crop cycles.

The impact of these practices extends beyond Pune to drought-prone areas such as Marathwada, encompassing talukas like Beed, Osmanabad, Latur, and Nanded. Here, the organization deploys Krishi Samvad Sahayaks (KSSs) to guide sustainable farming techniques. As a result, Swayam Shikshan Prayog has supported over 41,000 women farmers in managing approximately 30,000 acres of land, leading to a remarkable 25% increase in crop yields. Their efforts have earned them accolades, including NITI Aayog’s Women Transforming India Award and the Local Adaptations Award at COP-27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt.

Overall, Pune’s encouragement of diverse agricultural methods is creating a positive ripple effect throughout Maharashtra, leading to more sustainable farming, improved livelihoods, and greater resilience in the face of climate challenges. The collaborative efforts of local communities, NGOs, and government bodies are shaping a promising future for agriculture in the region.

Festivals/Rituals Related to Farming

Gudi Padwa

Gudi Padwa is the harvest festival that marks the end of the Rabi crop for the season. This is the time when fruits, especially mangoes, are reaped. One would witness the arrival of mangoes during this festival in the markets. This festival is considered an auspicious day for the Hindus as it also marks the beginning of a new year. During this festival, people hoist a special Gudi, a flag-like structure, in their houses. A bamboo stick is adorned with an upturned copper or silver pot and is garlanded with mango or neem leaves, flowers (frangipani or Champa in Hindi), and a beautiful cloth or saree. People draw rangolis beside the gudi and outside the door. As prasad, neem chutney is prepared, which also contains coriander seeds and jaggery. On this auspicious occasion, people buy gold and other things.

Types of Farming

The Sahyadri mountain range runs north-south in the western part of the Pune district. Here, farmers cultivate a variety of crops, including rice, wheat, jowar, bajra, sunflower, sugarcane, groundnut, gram, safflower, and a wide array of vegetables. Rice holds particular significance, especially in the talukas of Velha, Purandar, Bhor, Maval, and Mulshi, where the high rainfall creates ideal conditions for its growth. While cultivating paddy can be labor-intensive and costly, it can also yield significant profits if weather conditions remain favorable.

Slash-and-Burn Cultivation (JHUM/ JHOO)

One traditional method practiced in this region is slash-and-burn cultivation, known locally as jhum or jhoo. In this technique, farmers select a small plot on a mountain slope densely covered with trees. They clear the land by cutting down and burning the trees, then prepare it for planting during the monsoon season.

This land, often unclaimed by either the forest department or other farmers, is left fallow after harvesting, allowing the forest to regenerate for future use.

Raab is a specific form of this practice, where biomass is gathered in layers, using leaf litter and pruned branches, burned just before the rains, and then used for planting paddy seeds after the first showers. At the beginning of the full-fledged season, this area around the nursery of saplings is plowed, and the germinated seedlings that grow around 50-60 cm long are transplanted to the prepared land. This method, rooted in tradition, has been passed down through generations, primarily among the Maratha, Mahadev Koli, and Baudha communities.

Sustainable Farming

While traditional farming methods persist, recent trends show a shift toward sustainable practices. Research indicates that since 1990-91, the cropping patterns in areas like Mulshi, Maval, and Velhe have evolved to include combinations of fodder crops with rice and jowar. In drier regions like Purandar, Daund, and Shirur, farmers are increasingly opting for less water-intensive crops like jowar and bajra. Additionally, the northern and eastern talukas, such as Ambegaon and Pune City (Haveli), have seen a move from two-crop to three or even five-crop systems, thanks to improved irrigation and farmer prosperity.

Despite these advances, women in agriculture face significant challenges. The 2011 Census revealed that while 80% of female workers are involved in farming, only 13% own land in their name, despite working 1.4 times more than men. This highlights the disproportionate burden of unpaid work they carry, despite their crucial role in agricultural production.

Traditional Agricultural Practices

In Pune's agricultural landscape, traditional practices remained vital to farming communities. The tools of the trade included the plow (nangar), seed drills (pabhar and moghad), hoes (kulav, kulpe, or joli), beam-harrow (maind), dredge or scoop (petari), and cart (gada). Each tool served a specific purpose, reflecting the ingenuity of local farmers.

As the gazetteer mentions, the sowing of early kharif crops began in May or June, once the soil was adequately moistened by rain. In the plains, seeds were sown using a drill and covered with a long-bladed hoe (pharat). For mixed crops, a technique called moghan was employed, where one drill tube was stopped to allow for alternate sowing methods.

In places like Kulavdi and Shirur, many local farmers recall practicing Nangarni before the rains, utilizing a structure called Kudov, where bels (bulls) were attached to the plow vessel to sow seeds effectively. Here, essential crops like harbara (chana ki daal), chowli, and jowar thrived. The phase of grass removal was referred to as kasha.

As the rainy season progressed, farmers engaged in perni, taking special care of their crops. Pest management was crucial; traditional remedies like virel were used when larger pests invaded. Additionally, gobar (manure) enriched the fields, which were carefully stored in a khat.

When it came to selling their produce, farmers discussed quantities in terms of rupees shekda, where shekda denoted a specific amount.

In areas like Kulavdi and Shirur, farmers recall how before the rain, farmers engage in Nangarni where they use Kudov, a vehicle structure that includes a bel (tilling) to prepare the soil, ensuring that seeds are well-planted in the soil. They cultivate essential crops such as harbara (chana ki daal), chowli, and jowar. The phase where the grass is removed is also colloquially known as kasha here.

During the rainy season, farmers practiced perni to ensure proper care for their crops. In areas like Kulavdi, Hingangaon, and Bhima Koregaon, they relied on traditional methods to manage pests. When large pests appeared, they utilized a medicine known as virel if gobar (manure) wasn't sufficient to drive them away; gobar was commonly used to enrich their fields. They would store this manure in a khat for easy access and use.

In conversations about quantities and selling their yields, farmers reminisced about their trips to the market, where they sold their produce to middlemen and charged based on rupees shekda, with shekda indicating a specific quantity of produce.

Irrigation relied heavily on nearby river bodies, with farmers using traditional vessels like ghagri (matka) to fetch water. Their dependence on structures like the vihir (well) underscored the critical role of rainwater for irrigation; without it, water became a scarce resource. Many farmers recalled living for several months in kopat (house-like structures) to protect their fields, which were vulnerable to animal intrusions. To safeguard their crops, they employed traditional methods such as ghopan (a whip-like device) and mansa sa putla (scarecrow), reflecting their deep-rooted connection to the land and the challenges they faced in agricultural life.

Use of Technology

Baramati taluka in Pune is the turf of the famed Pawar clan who have dominated Maharashtra politics for decades. The Nationalist Congress Party led by Sharad Pawar (NCP Sharad) has won the Baramati Lok Sabha and assembly seats since the 1990s. Pawar was a six-time MP and his daughter Supriya took over from him in 2009 becoming a 4-term MP today. Pawar has always believed in modernizing agriculture and farmers' welfare, piloting many projects in his home constituency.

Under his supervision, Baramati’s Agriculture Development Trust (ADT) introduced a course in Artificial Intelligence (AI) designed by Oxford University for farmers to increase the average crop yield. The ADT was founded by Sharad Pawar and his elder brother, Dr. D.G. “Appasaheb” Pawar (1930-2000) to cater to underprivileged farmers and impart to them the best agricultural practices. They started their work by constructing water percolation tanks in Baramati tehsil in 1967, and the ADT was formed in 1971 to institutionalize these different activities in the region.

Irrigation projects play a crucial role in supporting the agricultural landscape of the Pune district. With 24 major and minor irrigation projects in the area, farmers benefit significantly, not just in Pune but in neighboring districts as well. Out of these, the Khadakwasla, Chaskaman, Nira Deoghar, Pawana, Temghar, and Varasgaon are considered to be the most important projects. Recently, the State Government of Maharashtra approved funds for the Nira Deoghar and Purandar Irrigation Projects, both of which are located in the Pune district.

In recent years, the introduction of mechanization and tech-enabled solutions like drones, coupled with rising agricultural distress, has led to a labor shortage in Pune’s agricultural market. Despite being a vegetable-export hub, there is a noticeable trend of farmers shifting their focus to sugarcane cultivation due to labor scarcity. The costs for hiring labor have escalated from ₹250-300 to ₹350-450, driven by workers moving to urban jobs. Consequently, the short-duration growth cycles of vegetables are increasingly being replaced by the longer-duration requirements of sugarcane.

Institutional Infrastructure

In Pune, the rapid development of infrastructure has raised concerns about the diminishing farmland, as green spaces give way to real estate projects. This urban expansion poses a risk of disconnecting agrarian communities from their ancestral occupations. As the demand for housing and commercial space in Pune surged, many farmers found themselves at risk of losing their land.

At present, Pune's farmers have played a significant role in the city’s real estate sector, supported by their financial and political clout. Actively engaged in local politics, these farmers leverage their substantial landholdings, positioning themselves as key players in a development process often characterized by political complexity. The ongoing conversion of agricultural land into urban developments reflects a broader trend in the region.

Magarpatta City, located on the eastern edge of Pune, is a noteworthy example of this shift. Built on land that has been owned by the Magar farming community for over 300 years, this area now hosts a large industrial estate and numerous IT and biotechnology companies, fueling strong demand for residential and commercial spaces.

Faced with the prospect of losing their homes and livelihoods, the farmers realized they needed to take proactive steps. Many smaller farmers had already begun to sell their land, and the Magar community understood that outside developers would soon approach them to acquire their properties. Instead of selling, they chose to pool their land and develop it collectively.

What distinguishes Magarpatta City is that it was conceived through a collaboration of landowners, without the involvement of traditional real estate developers. In a sector that often relies heavily on personal connections, particularly within government, this approach was unconventional. The farmers established the Magarpatta Township Development and Construction Company (MTDCC) to manage the development process, ensuring they maintained control over the project.

To prepare for this initiative, some farmers were trained in construction practices across India, while others acquired skills in construction management through local technical institutes. This training not only reduced construction costs but also facilitated a smoother transition for farmers into new occupations, helping them avoid unemployment as their land shifted from agricultural to urban use.

The paper, From Farming to Development: Urban Coalitions in Pune, India by Neha Swami illuminates how the farmers were actively involved in the construction process, using their farming equipment for various tasks, including laying bricks and managing the project. The initial phase of construction included building villas, apartment blocks, commercial spaces, and part of an IT park.

Post-development, many farmer families continued to live on-site, owning apartments or villas purchased with profits from the project. Some have successfully rented out their properties, generating additional income. The land remains registered in their names, providing a sense of ownership and security. Furthermore, many families have ventured into new businesses, leading to the rise of local services such as cable TV providers, catering, and transportation. This transformation in Pune exemplifies how agricultural communities have adapted to urban pressures by leveraging their resources and networks in the region.

Market Structure: APMCs

Pune City is home to the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) market at Gultekdi, a bustling hub where fresh fruits and vegetables from surrounding talukas begin arriving as early as 3 am. This market plays a crucial role in the daily trading of a significant share of the district’s agricultural produce.

Over the years, horticulture in Pune has flourished, driven by its strategic proximity to Mumbai and the support from the Maharashtra government and the Agriculture Produce Export Development Authority (APEDA). The Indian Council of Agricultural Research's Agricultural Technology Application Research Centre (ATARI), established in 2015, spearheads technological advancements in the region.

However, despite initiatives like the Electronic National Agricultural Marketplace (e-NAM) introduced by the Union Agriculture Ministry, many farmers in Pune remain reliant on APMC mandis and informal networks for selling their produce. Currently, only 118 out of the 295 mandis in Maharashtra are integrated into the e-NAM portal, indicating a lack of full adoption of this platform among farmers. Interestingly, Maharashtra boasts the highest number of Farmers' Produce Organizations (FPOs) registered on the portal, yet their effectiveness is often undermined by political interests.

Pune's Farmer Producer Companies (FPCs) have become politicized, often influenced by vested interests. Those in leadership positions at APMCs and FPCs frequently utilize their roles to further personal agendas or launch political careers. Many politicians have established cooperative sugar mills and poultry businesses, leveraging these enterprises to support their political ambitions. Despite this, the political capital held by Pune’s farmers allows them to advocate for local issues throughout the year. Interestingly, Pune’s FPCs were in support of the controversial agricultural laws passed by the central government in 2020. Farmers expressed concerns about the APMC cess, which they argued increases their operational burdens and limits their ability to trade independently.

Farmers Issues

While Pune’s farmers benefit from a robust supply chain network for marketing their produce, many remain unaware of government schemes and institutional credit options. For instance, the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY), which offers subsidies for farmers to build homes, has not been effectively communicated to the community. Despite receiving ₹325 crore in funding, the Pune Metropolitan Region Development Authority (PMRDA) has struggled to raise awareness and process applications, often dismissing them over minor bureaucratic issues.

The relationship between farmers and APMCs is complex and characterized by a mixture of reliance and frustration due to political interference. This tension has been particularly evident in the ongoing disputes over key crops like tomatoes, onions, and potatoes (TOP vegetables). Protests in 2023 by onion farmers from Manchar and Ghodegaon highlighted the need for a National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation (NAFED) procurement center to mitigate transport losses and enhance local procurement. The absence of such a center in Pthe une district has compounded their challenges.

Farmers' frustrations were exacerbated by the abrupt ban on onion exports and the imposition of heavy export duties, leading to significant losses as stored produce began to decay. In response to these challenges, the Onion Farmers’ Association established a center in Pune to facilitate direct sales to consumers, showcasing the farmers' creativity and resilience in navigating their difficulties.

In addition to this, Pune’s farmers have faced persistent issues over the last two decades. Despite having access to ample water resources and quickly adopting technology, agricultural distress continues to impact yields. Climate change has introduced unpredictability, with unseasonal rains damaging standing crops. These shifts in climate lead to moisture stress and delays in crop cycles, compounding the difficulties faced by farmers in the region.

Graphs

Irrigation

Cropping Metrics

Land Use and Credit

Sources

Agriculture Development Trust. Baramati.https://agridevelopmenttrustbaramati.org/

Ajay Jadhav. No date.Pune: INR325 cr allotted under PMAY fails to reach beneficiaries. Pune Mirror.https://punemirror.com/pune/civic/pune-inr32…

Anjali Sethi. 2019.Prema Gopalan. The Indian Wire.https://www.theindianwire.com/people/prema-g…

Dheeraj Bengurt.2023.Farmers to start centres to sell onion directly to customers, first centre planned in Pune. Hindustan Times.https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/pune-n…

Dr..S.A.Gaikwad. 2022. Traditional Cultivation Practices and Landraces of Rice from Velhe Region of Pune District, Maharashtra State. Vol. 7, no. 8.International Journal for Research Trends and Innovation.

Gazetteers Department. 1885, Reprinted: 1992.District Gazetteers, Poona District. Castes, Rainfall, Husbandmen and Soils.Government of Maharashtra.

https://gazetteers.maharashtra.gov.in/cultural.maharashtra.gov.in/english/gazetteer/Poona%20District/Poona-II/agri_husbandmen.html#.https://gazetteers.maharashtra.gov.in/cultur…

https://www.ijrti.org/papers/IJRTI2208186.pdfhttps://www.ijrti.org/papers/IJRTI2208186.pdf

Kailas Kokare. No date.Sahyadri farmers practice shifting cultivation amid ecological concerns. Village Square.https://www.villagesquare.in/sahyadri-farmer…

Kajale, Jayanti, and Atreyee Sinha Chakraborty. 2022. Role of Women in Agricultural Sector: Case in Maharashtra.Agro-Economic Research Centre, Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics..https://desagri.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/20…

Kumar Bose, Hiren. 2022.“‘Super Figs’: Why figs from Western Ghats hills in Pune are high in demand.”Village Square.https://www.villagesquare.in/purandar-farmer…

Maharashtra. Vol. 38, no. 2.Maharashtra Bhugolshastra Sanshodhan Patrika

Manoj More. 2021.Pune: Farmer producer companies welcome repeal of farm laws. Indian Express.https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/pun…

Memane, Dr. Shashikant R. 2021. A Geographical Analysis of Crop Combination Region in Pune District,

Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare.2021.Successive Stories of Progressive Women Farmers and Agripreneurs.Government of India..https://agriwelfare.gov.in/Documents/Success…

Neha Sami. 2012. From Farming to Development: Urban Coalitions in Pune, India. Vol. 37. No. 1.International Journal of Urban and Regional Research.https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1…

Parthasarathi Biswas. 2023.Year-ender 2023: Late monsoon, agricultural distress prevented Pune farmers from reaping good returns. Indian Express.https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/pun…

Radheshyam Jadhav. 2021.14% of APMC mandis’ farmers have joined e-NAM. The Hindu Business Line.https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/data-st…

Sandip Dighe. 2023.Protesting Manchar farmers halt auction of onion in APMC. Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/pun…

Seema Prasad. 2022.This Pune non-profit led by women bagged an award at COP27 for climate adaptation. Down To Earth.https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/agricult…

Shrikant Paranjpe. 2021.Poona’s coffee connection: An affair that began in 1839...Hindustan Times.https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/pune-n…

Staff Reporter. 2023.Maha govt approves funds for two irrigation projects in Pune dist. Hindustan Times.https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/pune-n…

Staff Reporter. 2023.Use of AI in agriculture course to be introduced in Baramati. Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/pun…

Staff Reporter. 2025.Beekeeping: 100 Women From Rural Maharashtra Launch Their Journey Towards Economic Independence. Punekar News.https://www.punekarnews.in/beekeeping-100-wo…

Staff Reporter. 2025.Why Is Pune Anjali’s Model Of Poshan Vatika A Hit. Kisan of India.https://eng.kisanofindia.com/latest-news/why…

World Economic Forum. Orghttps://www.weforum.org/

Last updated on 7 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.