Contents

- Physical Features

- Climate

- Geology

- Soil

- Minerals

- Rivers

- Botany

- Wild Animals

- Birds

- Snakes

- Land Use

- Forest Reserves

- Bhimashankar Wildlife Sanctuary

- Bhigwan Bird Sanctuary

- Environmental Concerns

- Air Pollution

- Water Pollution

- Deforestation and Loss of Biodiversity

- Waste Management

- Conservation Efforts/Protests

- Taljai Bachao Andolan

- Protests at Vetal Tekdi

- Climate Change Protests

- Riverfront Development Project Opposition

- Resistance Against Dow Chemical Facility

- Budgetary Allocation Protest

- Environmental NGOs

- Applied Environment Research Foundation (AERF)

- Bird Conservation and Citizen Science

- Forrest India

- Grasslands Trust

- Jeevitnadi: Living River Foundation

- Kirloskar Vasundhara Film Festival

- Parisar

- RESQ Charitable Trust

- Sarpa Mitras (Snake Friends)

- Shashwat Eco Solution Foundation

- TERRE Policy Center

- Vasundhara Abhiyan

- Cultural Connections with Nature

- Graphs

- Water

- A. Rainfall (Yearly)

- B. Rainfall (Monthly)

- C. Evapotranspiration Potential vs Actual Numbers (Yearly)

- D. Annual Runoff

- E. Runoff (Monthly)

- F. Water Deficit (Yearly)

- G. Water Deficit (Monthly)

- H. Soil Moisture (Yearly)

- I. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Bore Wells

- J. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Dug Wells

- Climate & Atmosphere

- A. Maximum Temperature (Yearly)

- B. Maximum Temperature (Monthly)

- C. Minimum Temperature (Yearly)

- D. Minimum Temperature (Monthly)

- E. Wind Speed (Yearly)

- F. Wind Speed (Monthly)

- G. Relative Humidity

- Human Footprint

- A. Nighttime Lights

- Sources

PUNE

Environment

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Pune district, in the Maaval region of Maharashtra, lies between the Western Ghats (Sahyadri Hills) and the Deccan Plateau. Over the centuries, various dynasties ruled Pune, but it saw major growth during the Peshwa era, which brought urban planning and improved water systems.

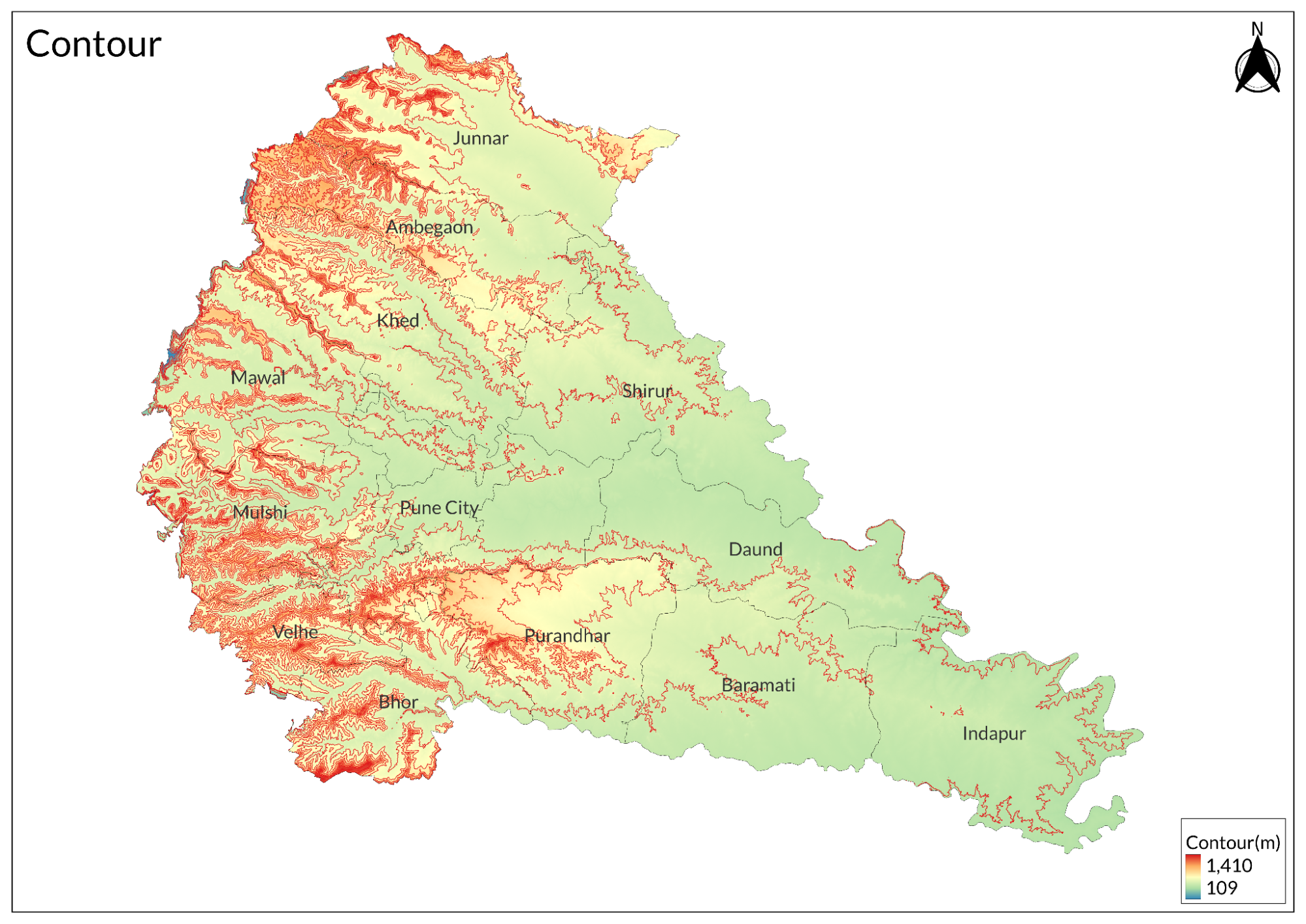

Physical Features

Pune district is located in the western part of Maharashtra. Situated at an elevation of 560 m above mean sea level, it spans an area of 15,643 sq km. The district is bordered by Ahmednagar district to the northeast, Solapur district to the southeast, Satara district to the south, Raigad district to the west, and Thane district to the northwest. It is divided into 14 tehsils.

Pune district lies within the Western Ghats, also known as the Sahyadri mountain range, extending to the Deccan Plateau in the east. The hills of the district belong to two distinct systems: one generally running north-south, forming the main range of the Sahyadris. The prominent peaks include Harishchandragad in the extreme north (located in Ahmednagar district), which has mighty scarps nearly 1,219 m high. The next significant hill is Dhak in Raigad district. Southwest of Dhak lies the notable ghat of Ahupe. A few kilometers south of Ahupe stands Bhimashankar, a sacred source of the river Bhima. South of Bhimashankar rises the famous double-peaked fort of Rajmachi.

To the south, a steep slope ends westward in a sheer cliff known locally as Cobra's Hood or Nag-phani and referred to by Europeans as Duke's Nose. Further south rises Tamhini Ghat and Jambuni Hills. The four belts form the main line of the Sahyadris and run eastward. Among these, five chief spurs are notable: Tasobai Ridge, which passes east within a few miles of Talegaon-Dabhade; Shridepathar, dividing the valleys of the Andhra and Kundali rivers; Vehergaon spur; Sakhupathar plateau; and an offshoot with four peaks—Lohgad, Visapur, Batrasi, and Kudva—separating the valleys of the Indrayani and Pawana rivers, stretching east to the boundary of Haveli sub-division.

Further south, within Bhor limits in the Pawana valley, rises a spur from which two peaks, Tung and Tikona, emerge. Other prominent hills surrounding Pune city include Vetal Hill, Parvati Hill, Baner Hill, Chaturshringi Hill, Dighi Hills, Durga Hill, Taljai Hills, Katraj Hill, Gultekdi Range Hills, Dive Ghat, and Fergusson Hill.

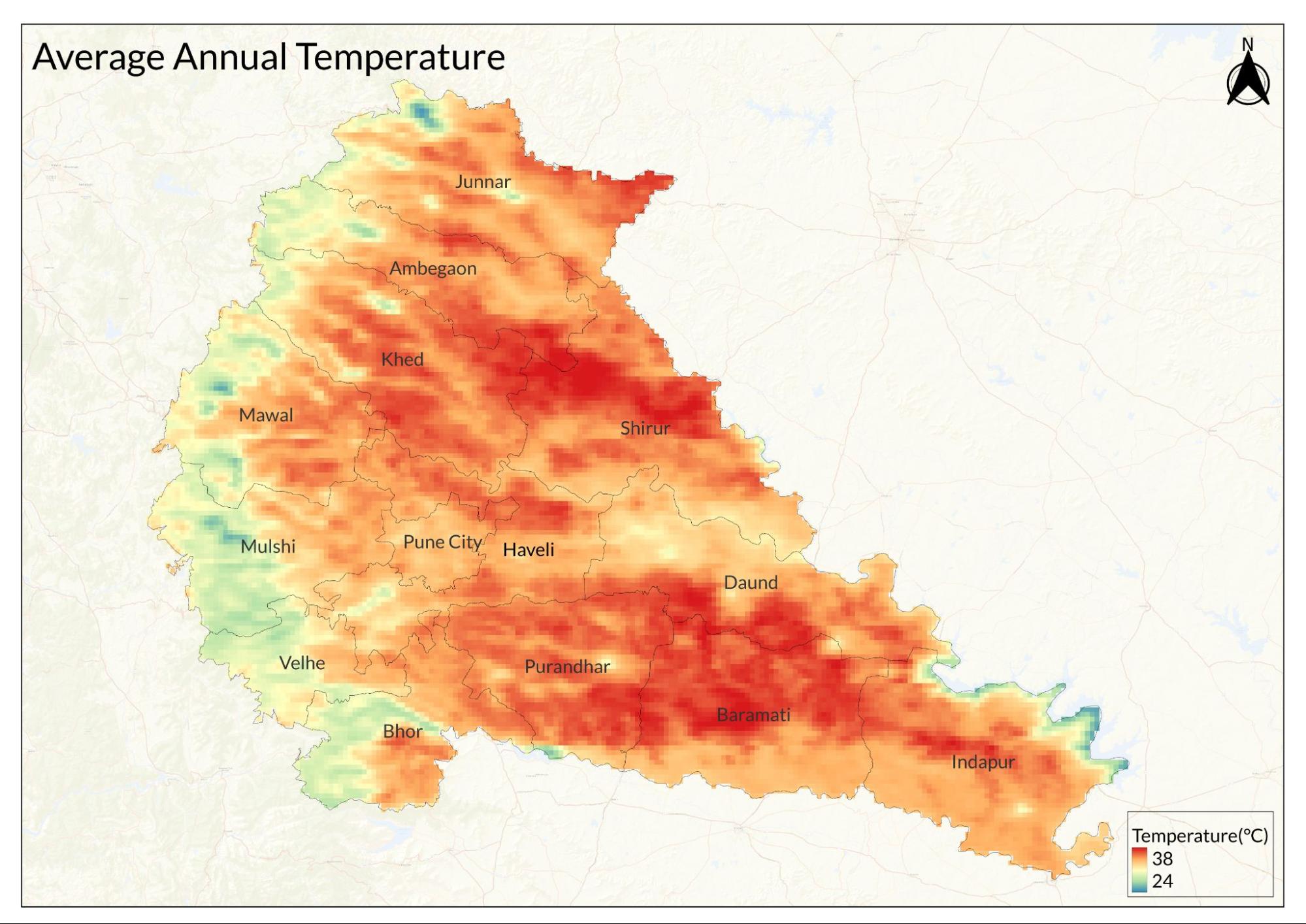

Climate

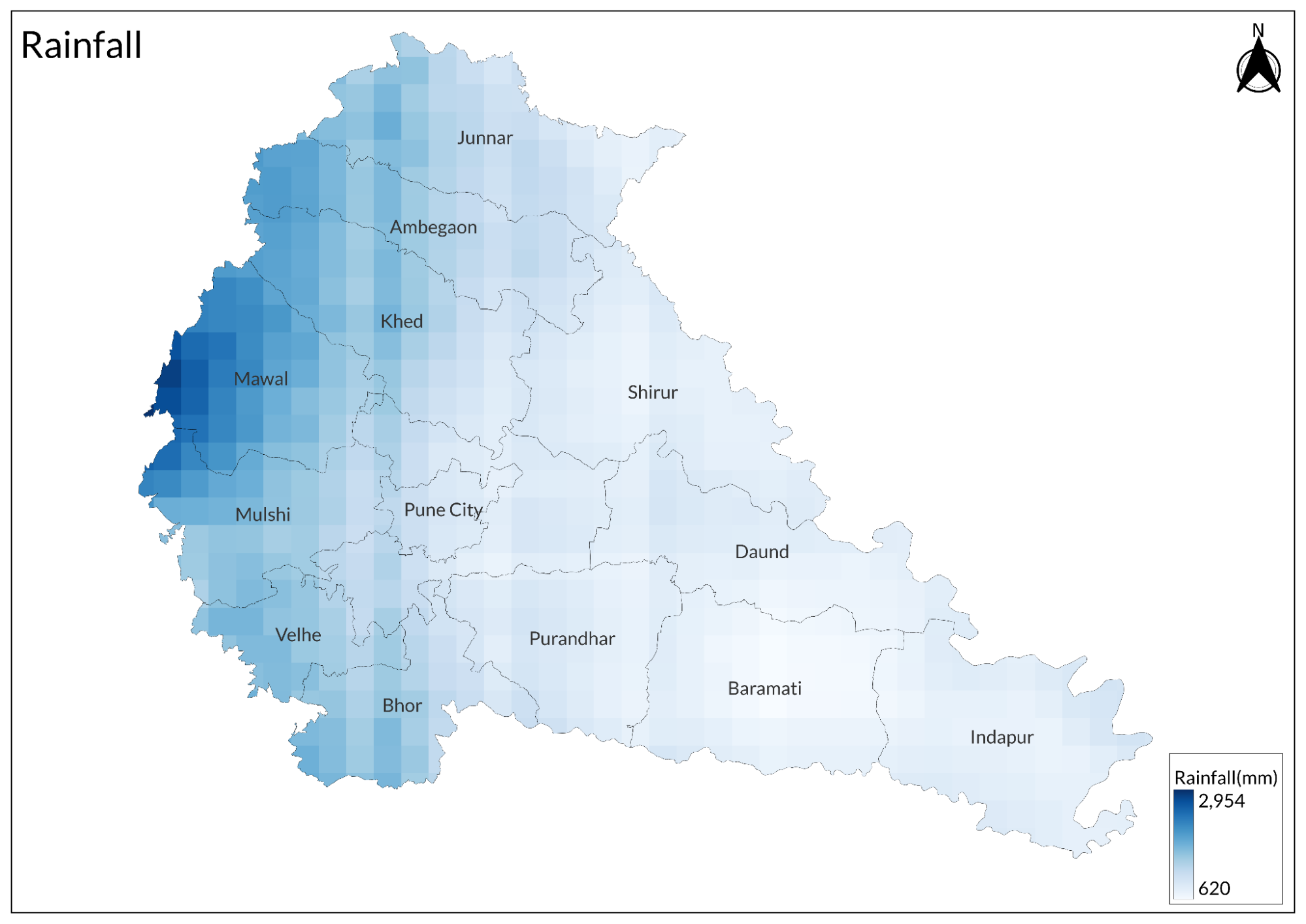

The district is known for its excellent weather. Pune has a tropical wet and dry climate, with average temperatures ranging between 20°C and 28°C. The summer season starts from March until May, with the average temperature lying between 30°C and 38°C. April is the warmest month. During the summer season, the nights are usually cool due to the high altitude. The monsoon starts from June until October, and the average rainfall received is 650 to 700 mm. July is the wettest month of the year. Winter begins in November and lasts until February, with daytime temperatures hovering around 28°C while night temperatures are below 10°C for most of December and January, often dropping to 5 or 6°C.

The maximum rainfall recorded in Pune district is 2,691 mm in Velhe tehsil, and the lowest rainfall recorded is 394 mm in Baramati Tahsil.

Geology

The entire district consists of a Basaltic rock formation called the ‘Deccan trap’.

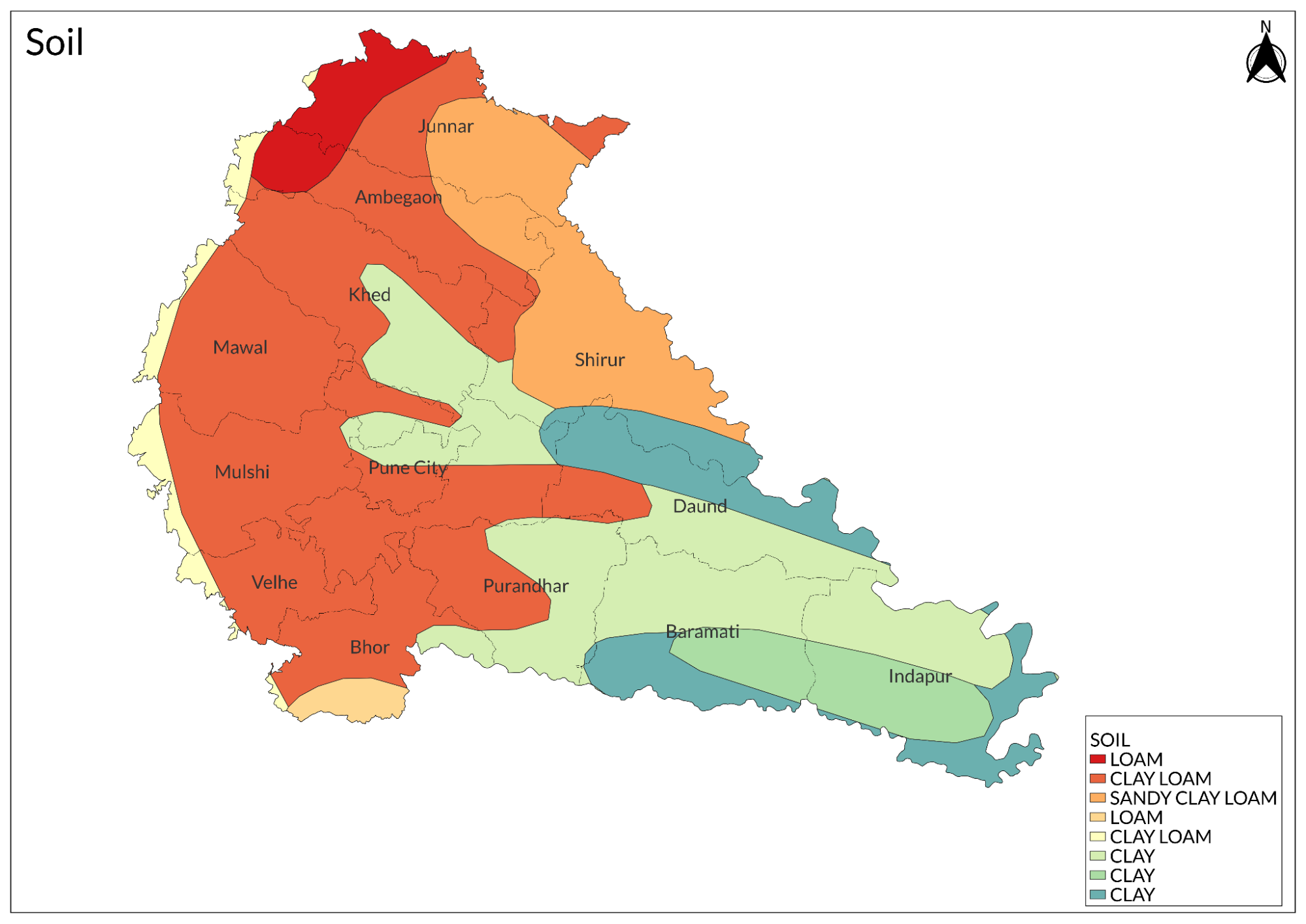

Soil

Five different types of soil found throughout the district are as follows: deep, moderately well-drained, strongly calcareous soil; slightly deep, well-drained, fine calcareous soil; very deep, well-drained loamy soil; and shallow drained clayey soil.

Minerals

Building stones and basalts were primarily found in the western regions of the district. Quartz occurs throughout the trap in various forms, either crystalline or amorphous. Quartz was very common near the banks of the Mula and Mutha rivers, as documented in the revised gazetteer of 1954. Common salt is found in the bed of a rivulet at Kund Mavli, near the falls on the Kukdi River, between Sirur and Kavtha. Carbonate of soda occurs in a few places, occasionally forming an efflorescence on the surface. Washermen use earth impregnated with this salt for washing clothes. Soda is also found mixed with earth near Sirur, where it is dug out and sold for washing. Limestone yielding useful lime occurs in several places. There are good quarries near the villages of Phursungi and Vadki at the foot of the Diva Pass, about ten miles southeast of Poona, as well as near Uruli, Yevat, Kedgaon, and Dhond in the Bhimthadi sub-division.

Rivers

Bhima, Nira, Indrayani, Mula, Mutha, Ghod, Meena, Kukdi, Pushpavati, Pavna, and Ramnadi are the major rivers of the district. The Bhima River is the principal river in the district, originating from Bhimashankar in the northwest and flowing southeast. Ghod, Mutha, and Nira are tributaries of Bhima. The delta formed by the Nira and Bhima rivers is located near Narsimhapur. The Nira River flows from the southern part of the district, generally moving from west to east. Karha is a tributary of the Nira. The Ghod River traverses the northern part of the district, with Kukdi and Meena as its tributaries. Other notable rivers include Mandvi, Pushpavati, Indrayani, Bhama, and Pavana. The Pavana River crosses the city of Pune; it originates south of Lonavala in the Western Ghats and flows approximately 60 km before merging with the Mula River. Among these rivers, the Mula and Mutha flow through the center of Pune city. Additionally, other significant rivers in the district, including Ramnadi and Bhima, are highly polluted due to urbanization and the dumping of industrial and domestic sewage.

The water supply for Pune city is primarily sourced from the Khadakwasla Dam. Groundwater serves as a major source of drinking water in other regions of the district, while river water is utilized for irrigation purposes.

Botany

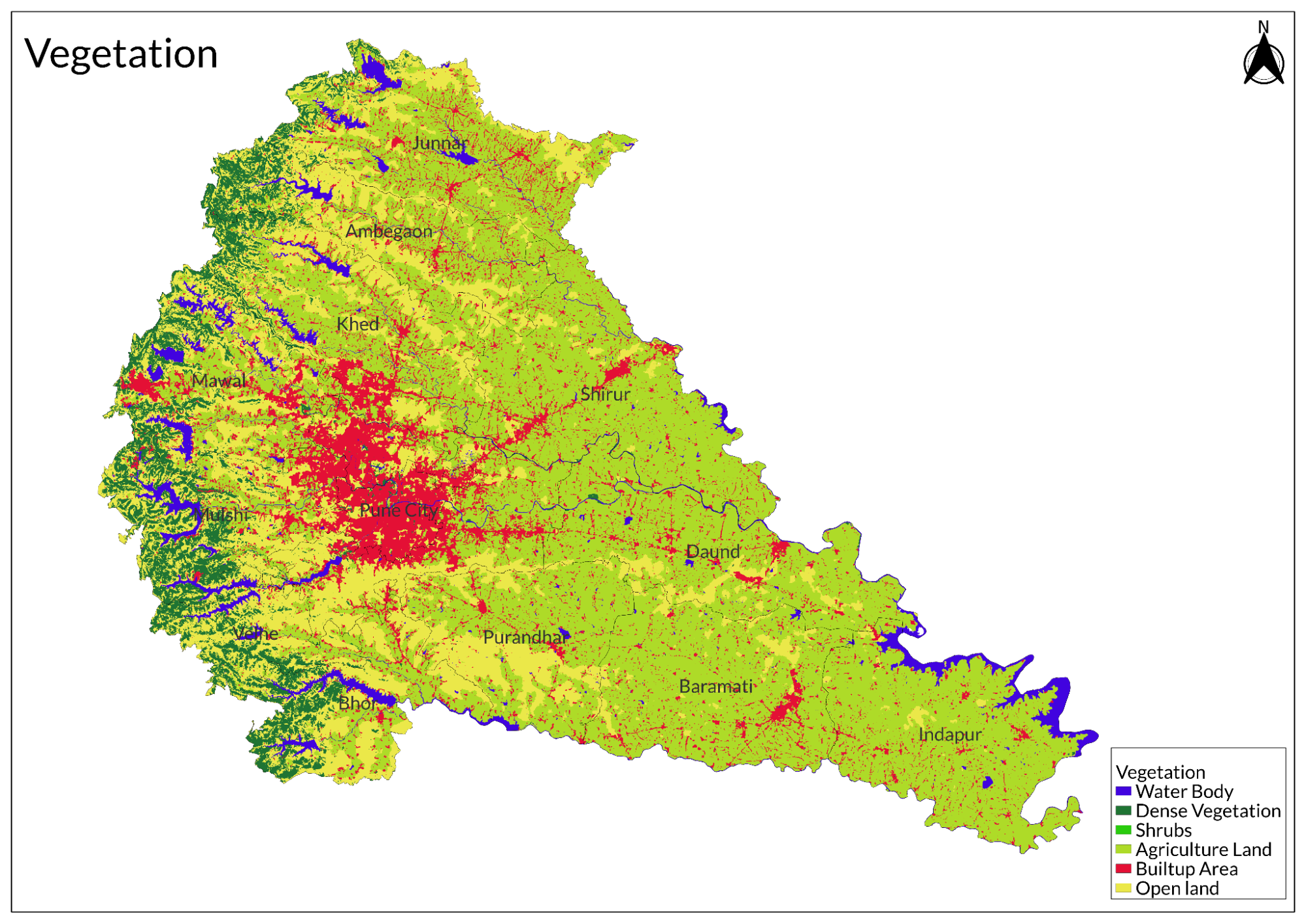

The district encompasses three main types of forests: scrub, mixed deciduous, and evergreen. This diversity can largely be attributed to the rainfall patterns across different altitude zones. Species such as Bor, Polati, and Hinganbet are found in the eastern altitudinal belt, where rainfall does not exceed 20 inches, supporting thorny scrub vegetation.

Closer to the center of the country, deciduous species predominate; however, many native tree populations are severely threatened by over-harvesting, with the exception of teak. In the western part of the district, where rainfall is more abundant, evergreen species such as Ain and Hirda are prevalent. Prosopis juliflora is also valuable for its fruit in the Karwand hills and surrounding areas.

The western extremes are covered by climax evergreen forests at Bhimashankar near the temple and close to Ahupe village in Ambegaon tahsil, which are dominated by species like Anjani and Jambul. The distribution of forest types varies by tahsil: Junnar, Ambegaon, Khed, Mawal, Mulshi, and parts of Haveli have substantial areas under evergreen and mixed deciduous forests. In contrast, the eastern parts of the district, particularly in talukas like Daund, Indapur, and Sirur, have very scant forest land as it is primarily used for pasture.

Wild Animals

Due to hunting in the last century, the number of wild animals has significantly decreased. As documented in the British Gazetteer of 1814, the most prominent wild animals—such as tigers, panthers, leopards, sloth bears, wild pigs, sambar deer, spotted deer, barking deer, jungle cats, common palm civets, and kolhas—were once fairly plentiful in the Sahyadari forest area, particularly in the forests of Lonavala and Khandala. Currently, these wild animals are found only in the forest reserves of the district.

Giant squirrels inhabit the Ghat forests. The black-napped hare resides in scrublands, while the Indian mole rat and Indian field mouse are commonly seen around cultivated areas. Common mongooses are present throughout the district. According to the British Gazetteer of 1814, antelopes like nilgai and blackbuck inhabited open grassy plains and were known for damaging crops, while Indian gazelles are now only found in forest reserves.

The pangolin or scaly anteater is a unique nocturnal mammal characterized by its hard, overlapping scales. Rarely encountered animals include striped hyenas, common palm civets, four-horned antelopes, mouse deer, wolves, and wild dogs—the latter being destructive to game and historically found in the Sahyadri forests but now restricted to forest reserves.

Birds

Around 300 different bird species are found throughout the district, of which approximately 90 are migratory species, mostly spotted during the winter season. Migratory birds include the Common Teal, Garganey (or Blue-winged Teal), Shoveler, harriers, and Tufted Pochard, which are primarily found near water bodies. Snipes are typically found in paddy fields and include species such as fantails, pintails, and wood snipes. Comb ducks and common cranes are also present.

Weaver birds in the district include the house sparrow, grey partridge, painted partridge, titar, green pigeons (particularly the yellow-legged green pigeon), sandgrouse, and small numbers of painted sandgrouse. Pigeons, especially blue rock pigeons, commonly inhabit all hill forts. Rain quail and rock bush quails are also found in the area. Peafowl thrive in the forested or hilly regions of the district.

The Great Indian Bustard is found in plains and open grassy regions and is now on the verge of extinction.

Land birds in the district include grey and painted partridges as well as rain and jungle quails. Green parakeets, which are largely destructive to fruit and field crops, are also present. The three parakeet species found in the district are the Large Indian Parakeet, Rose-winged Parakeet, and Blossom-headed Parakeet.

Four species of sunbirds are commonly found in the district: the Purple Sunbird, Purple-rumped Sunbird, Small Sunbird (confined to evergreen hill forests), and Yellow-backed Sunbird. The two flowerpecker species occurring in the district are the Thick-billed Flowerpecker and Pink-billed Flowerpecker (also known as Tickell's Flowerpecker).

Commonly observed birds include the Black-headed Oriole, Myna, green parakeets (largely grass-green), kingfishers, Khandya, Ganya, Dicca (white-breasted myna), small-sized sparrows, and bee-eaters (including small green varieties and roller or blue jay pigeons).

Sunbirds found in the district also include the Spotted Babbler and Black-capped Blackbird (chiefly in hill forests such as those at Khandala, Bhimashankar, and elsewhere), as well as the Dhayal. The song of the Dhayal, delivered from a roof or treetop, is one of the most familiar sounds in the countryside between February and May and is often heard near human habitations.

Snakes

Snakes are numerous throughout the district, especially in the western hilly tahsils of Junnar, Khed, Vadgaon, Maval, Mulshi, and Bhor. The mild temperature, thick forests, and hilly surroundings create ideal conditions for snake populations; therefore, a greater variety of snakes is found on the western side of the district compared to the central and eastern regions. In addition to a large number of non-poisonous snakes, all four common poisonous snakes of India—the cobra, Russell's viper, krait, and Echis (saw-scaled viper)—are present in this district.

In Pune city alone, the first three snakes are often encountered in the Chattushringi, Vetal Hills, and Yeravda regions, respectively.

Land Use

Forest Reserves

Bhimashankar Wildlife Sanctuary

It is renowned for its rich biodiversity and is considered one of the world's biodiversity hotspots. The sanctuary is home to various mammals, including barking deer, wild boars, and langurs, as well as a wide range of reptiles, insects, amphibians, and butterflies. The best time to visit is from October to February. Located in the Khed Tahsil of Pune District, the sanctuary offers safaris from dawn until 7 PM.

Bhigwan Bird Sanctuary

This renowned destination for bird enthusiasts is especially famous for its flamingos, making it a paradise for wildlife photographers and bird watchers. In addition to flamingos, visitors can spot numerous ducks, raptors, herons, and migratory birds such as painted storks, wild geese, and cranes. The best time to visit the sanctuary is from December to February.

Environmental Concerns

Air Pollution

Air pollution in Pune is a serious health concern. Studies show that 2018 was one of the most polluted years since 2013. The level of harmful air particles (PM2.5) increased by 60% over five years, going from 29 to 47 (above the safe limit of 40). The number of high-pollution days also rose from 73 in 2017 to 94 in 2018.

Experts say Pune’s air quality is consistently poor. Pollution levels are four times higher than what the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends. Harmful gases like sulfur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide also exceed safe limits, increasing breathing problems and other health risks.

Water Pollution

Water pollution in Pune is a major issue due to unequal water distribution and untreated sewage. Some areas receive 600 liters per person daily, while others get only 100 lpcd, leading to excessive wastewater and severe pollution in the Mula-Mutha rivers. Despite a 599 MLD sewage treatment capacity, much sewage remains untreated, worsening river pollution.

Pune’s water supply system is inefficient, with leakages reducing actual distribution. Some areas get water for less than two hours a day, while others enjoy 24-hour access. Low-lying areas receive more water than higher regions due to Pune’s hilly terrain. The city also relies on Khadakwasla Lake and 4,500 private tubewells, but groundwater quality is declining due to poor sanitation.

The PMC’s riverfront projects aim to improve riverbanks but face criticism for flooding risks and ecological harm. Financial challenges, Rs 306.47 crore in unpaid water dues, and conflicts over urban vs. agricultural water use add to the crisis.

Deforestation and Loss of Biodiversity

Pune district, located between the Western Ghats and the Deccan Plateau, was once rich in forests and biodiversity. However, rapid urbanization, industrialization, and human activities have led to deforestation and habitat loss over the years. Pune's hills were once covered in dense forests with teak trees, but centuries of degradation have turned them into grasslands and scrublands. Farming, grazing, and city expansion have worsened the damage. Reforestation efforts by the Forest Department have introduced non-native species, which disrupt the natural balance. Despite this, hills like Vetal Hill, Parvati Pachgaon Hill, and Baner Hill still provide shelter for birds like owls, eagles, and buzzards.

Urban growth has also broken up wildlife corridors. Baner Hill and Vetal Hill, which were once connected to the National Defence Academy (NDA), are now cut off by a highway, limiting animal movement. Pune’s biodiversity is shrinking fast—a study found that over 200 plant species along the Mutha River have disappeared in 66 years. 30% of Pune’s hill landscapes have been lost, affecting water sources and soil quality.

Some community efforts have helped restore degraded land. Baner Hill has seen the planting of native trees like apta, shisam, bahava, and ficus. While these efforts are helpful, much more is needed to restore Pune’s natural environment.

Waste Management

Pune district is struggling with a growing waste management crisis due to rapid population growth and urban expansion. The city generates 2,100 to 2,200 metric tons of solid waste daily, a number expected to increase. However, waste disposal infrastructure is inadequate, with much of the waste being dumped in landfills like Urali Devachi (Mantarwadi) without proper treatment. Poor waste segregation and recycling have worsened the problem, leading to overflowing and mismanaged landfills. The environmental and health impacts are severe. Open dumping releases harmful gases like sulfur dioxide (SO₂), methane (CH₄), and carbon dioxide (CO₂), contributing to air pollution and respiratory issues for nearby residents. Toxic leachate from decomposing waste contaminates groundwater, making it unsafe for drinking and farming.

Unmanaged waste also affects quality of life, creating foul odors, ugly waste piles, and declining property values near dumping sites. Outdated waste management systems, lack of recycling infrastructure, and limited investment in modern waste processing have made the situation worse.

Conservation Efforts/Protests

Taljai Bachao Andolan

Taljai Hill, designated as a wildlife reserve, is home to diverse plant and animal species. Residents have strongly opposed developmental projects by the Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) that threaten its ecological balance. In March 2022, Sahakar Nagar residents demanded the halt of large-scale concretization under the guise of beautification, forcing officials to cooperate with citizens' concerns. After a major fire in March 2024, the Sahakarnagar Citizens Forum urged the forest department to improve security and surveillance to prevent future incidents.

Protests at Vetal Tekdi

In May 2022, thousands of citizens protested against PMC’s proposed road and tunnel construction on Vetal Tekdi. The plan included surface routes and tunnels as part of traffic management solutions, risking significant green cover. Activists argued that increasing urbanization and vehicle-related pollution already posed severe environmental threats, emphasizing the need to protect this vital green space.

Climate Change Protests

In 2019, inspired by the global "Fridays for Future" movement, Pune citizens staged human chains and protests at locations like Alka Talkies and Camp. They demanded stronger conservation efforts for the Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary and greater accountability from local authorities on climate action.

Riverfront Development Project Opposition

In April 2023, around 2,000 residents joined a tree-hugging rally to oppose the Riverfront Development Project (RFD), which proposed developing a 44.4-km stretch along the Mula and Mutha rivers. The project involved felling many trees, sparking protests led by environmental NGOs. Participants rallied from Sambhaji Park to the Mutha riverbed near Garware Bridge, raising awareness and distributing pamphlets.

Resistance Against Dow Chemical Facility

In 2008, villagers in Khed Taluka protested the allocation of 40 hectares of grazing land to a Dow Chemical facility without their knowledge. The land transfer impacted their livelihoods, causing significant financial losses. Villagers demonstrated by cutting off water and food supplies to the facility. Additionally, concerns were raised about the hazardous chemicals Dow was authorized to use under the Environment Protection Act, 1980.

Budgetary Allocation Protest

In 2015, Pune-based NGO Jividha launched a protest against inadequate budgetary funds allocated to the environment and forest sector. They criticized the reductions in successive years and opposed the Subramanian Committee’s recommendations, which were viewed as anti-environment. As a symbolic gesture, citizens were urged to donate ₹1 to the PM Relief Fund to highlight the need for greater investment in pollution control and environmental protection.

Environmental NGOs

Applied Environment Research Foundation (AERF)

Focuses on biodiversity conservation through community-based efforts, engaging local populations for sustainable outcomes.

Bird Conservation and Citizen Science

Pune hosts an active birdwatching community that contributes to conservation efforts. The Pune Ladies Bird Group, with over 200 members, focuses on bird photography, documentation, and preservation. The Pune Bird Atlas, an initiative under BirdCount India, maps bird distributions using the citizen science platform eBird.

Forrest India

Based in Mulshi, this NGO works on biodiversity preservation, sustainable resource use, and fostering human-nature connections.

Grasslands Trust

Focusing on conserving wildlife in grasslands and scrublands, this Pune-based NGO engages in tracking and documenting wildlife behavior, particularly wolves and hyenas. They also work with local communities, including nomadic shepherds and farmers, to promote conservation. Projects include drone-based wildlife tracking, studies on wolf behavior, and conservation awareness programs.

Jeevitnadi: Living River Foundation

Jeevitnadi is dedicated to the revival of Pune’s rivers, particularly the Mula-Mutha. Operating under the motto “My River, My Responsibility,” the organization emphasizes citizen participation in river restoration. Inspired by ecologist Prakash Gole, they conduct projects like "Adopt a River Stretch," organize river walks, garbage-cleaning drives, and awareness campaigns, and host the Muthai River Festival featuring plays, storytelling, and other cultural activities by the riverbanks. They also run blogs and YouTube series to spread knowledge.

Kirloskar Vasundhara Film Festival

This annual festival showcases internationally acclaimed environmental films and documentaries. Alongside film screenings, the event includes conservation workshops, panel discussions, and nature walks to promote environmental awareness.

Parisar

This NGO advocates for environmental awareness, sustainable urban development, and conservation. Parisar played a key role in the formulation of Pune’s Tree Act by-laws, ensuring citizen involvement in the Pune Tree Authority. Their work includes promoting natural farming practices, improving air quality, and campaigning against single-use plastics.

RESQ Charitable Trust

Founded in 2007, RESQ Charitable Trust offers emergency aid to animals in distress. The organization has rescued and rehabilitated thousands of animals across 200+ species. Authorized by the Maharashtra Forest Department, RESQ operates a Wildlife Transit Treatment Centre in Pune for injured, orphaned, and trafficked wildlife. Their work extends to community animal care and wildlife conflict resolution.

Sarpa Mitras (Snake Friends)

Pune district also benefits from a network of trained Sarpa Mitras who safely handle and relocate snakes found in residential areas. This initiative has significantly reduced snake killings and raised awareness about snake conservation.

These collective efforts demonstrate Pune’s commitment to environmental sustainability and wildlife preservation through community participation and innovative practices.

Shashwat Eco Solution Foundation

Dedicated to sustainable development, this organization promotes rainwater harvesting, eco-friendly alternatives like Patraval (eco-plates), and biodiversity management.

TERRE Policy Center

Promotes afforestation, biodiversity sustainability, and environmental awareness through initiatives like Envirothons (marathons for awareness) and TERRE Olympiads for school children. They also offer fellowships for environmental and agricultural research.

Vasundhara Abhiyan

Established in 2006, Vasundhara Abhiyan focuses on conserving and restoring the Baner-Pashan hill. Their activities include planting and conserving over 40,000 plants, biodiversity restoration, rainwater harvesting, and soil conservation. They have constructed contour trenches, bunds, and water tanks to aid in these efforts. Educational initiatives such as seminars and drawing competitions for children help spread awareness.

They also use innovative planting methods, such as the Miyawaki forest technique, which involves planting native species close together. This method promotes faster growth, denser greenery, and reduced maintenance after three years. Another notable project is ‘Nakshatra Van,’ where plants are arranged to mimic zodiac constellations as described in the Vedas. Vasundhara Abhiyan has received recognition, including awards from the PMC and the Green Champion of Pune title.

Cultural Connections with Nature

Historical records from the Peshwa era reveal fascinating stories about the wild animals kept for training, gifts, or hunting assistance. For instance, Bajirao I sent two falcons and a cheetah to Shahu Maharaj, who had a passion for hunting. Shahu Maharaj was particularly fond of acquiring purebred hounds for training as hunting dogs. He also collected rare animals, such as Alpine deer (Kasturi mriga) and Himalayan pheasants, believing that the presence of a Himalayan pheasant would ensure a long-lasting kingship.

Nanasaheb Peshwa designated an area between Parvati Hills and Sarasbaug as a ‘Shikarkhana,’ which served as a sanctuary for various animals, including tigers, sambar deer, rhinoceroses, blackbucks, and trained falcons for hunting expeditions. A letter addressed to Vitthal Shivdeo mentions an order to procure a bird called “Chakor,” mythically known to feed on moonlight; in reality, this refers to the “Chukar,” a type of rock partridge.

A notable event during Madhavrao's wedding included a dramatic spectacle featuring the combat between a tiger and an elephant, resulting in the tiger's death. The Shikarkhana was not merely a zoo; it functioned as a sanctuary where animals could roam freely rather than being confined in cages. Historical accounts also mention that a lynx and a double-humped Bactrian camel were among the exotic animals housed in Pune’s sanctuary.

Graphs

Water

Climate & Atmosphere

Human Footprint

Sources

Civil Society Online. What is Pune Losing and How Fast?.Environmental Report.https://www.civilsocietyonline.com/cover-sto…

Hindustan Times. 2022.Sutradharas Tales: When Rhinoceroses, Tigers, and Elephants Roamed Pune City's Grounds.Hindustan Times,https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/pune-n…

Hindustan Times. 2022.Sutradharas Tales: When Young Peshwa Enjoyed the Company of Fearsome Animals.Hindustan Times,https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/pune-n…

Hindustan Times. 2023.Mutha River Bank Lost Over 200 Plant Species in Last 66 Years: Study.Hindustan Times,https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/pune-n…

Indian Science Congress Association (ISCA). 2011.Solid Waste Management Issues in Pune: Leachate and Decomposition Problems.Research Journal of Recent Sciences,https://www.isca.me/rjrs/archive/v1/iISC-201…

Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). n.d.Pune Air Pollution Report.NRDC Environmental Study.https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/med…

Pune Mirror. 2024.Mula River Pollution Worsens: Untreated Waste and Garbage Dumping Threaten Environment.Pune Mirror,https://punemirror.com/PCMC/mula-river-pollu…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.