Contents

- Crop Cultivation

- Agricultural Communities

- Festivals or Rituals Related to Farming

- Rituals during Perni

- Rituals during Mrug Nakshatra

- Types of Farming

- Step Farming | Farming in Hilly Regions

- Mango Picking

- Traditional Agricultural Practices

- Sheti in Ratnagiri: A Seasonal Journey

- Use of Technology

- Institutional Infrastructure

- Market Structure: APMCs

- List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

- Farmers Issues

- Climate Change and Its Impact on Agriculture in Ratnagiri

- Ratnagiri’s Monkey Menace

- Graphs

- Irrigation

- A. No. of Projects

- B. No. of Ponds/Vilage Lakes and Storage Dams

- C. Irrigation Beneficiary Area vs Irrigated Area

- D. Share of Beneficiary Area Irrigated

- E. Tubewells and Pumps Installed In The Year

- F. Irrigation and Water Pumping Facilities

- Cropping Metrics

- A. Share in Total Holdings

- B. Cultivated Area (With Components)

- C. Gross Cropped Area (Irrigated + Unirrigated)

- D. Share of Cropped Area Irrigated

- E. Distribution of Chemical Fertilizers

- Land Use and Credit

- A. Area of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- B. Size Groups' Share in Total Agricultural Land Holdings Area

- C. No. of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- D. Size Groups' Share in Total No. of Agricultural Land Holdings

- E. Agricultural Lending

- F. Agricultural Credit as a share of Total Credit

- Sources

RATNAGIRI

Agriculture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Ratnagiri, situated in the picturesque Konkan region of India, is defined by its vast open fields and predominantly agrarian population. Here, farming transcends mere livelihood; it embodies a rich ancestral tradition preserved through generations. Women play a vital role in this cultural legacy, working alongside men and taking the lead during the lavni of the paddy. The methods of cultivation in Ratnagiri are significantly influenced by the region's geography, which can be divided into hilly regions, foothills, and coastal plains. In the hilly areas, step farming is commonly practiced, while the foothills feature a combination of flat and step farming. The coastal plains, on the other hand, primarily utilize flat farming techniques.

Crop Cultivation

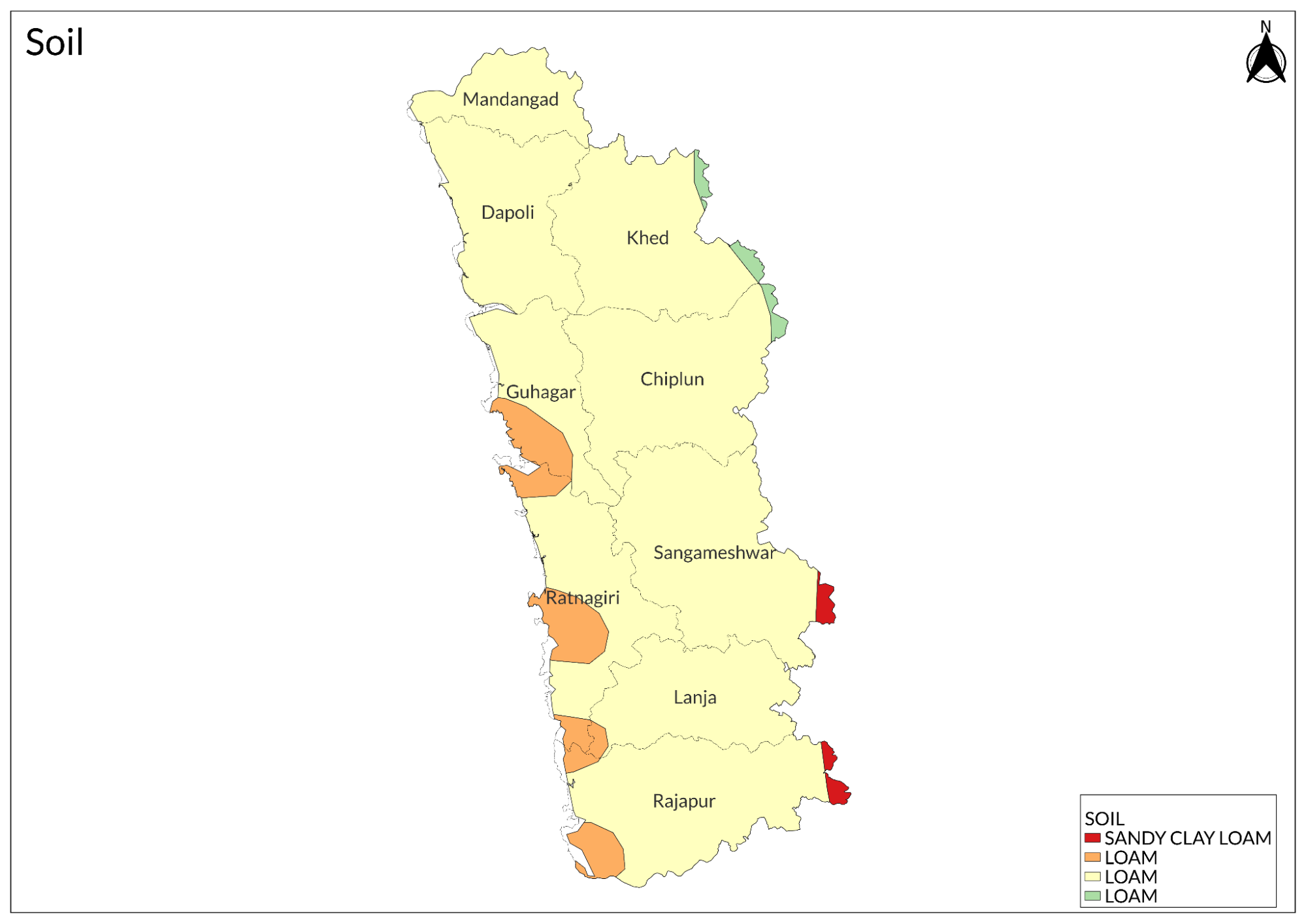

Ratnagiri’s landscape features a mix of hilly terrains, foothills, and coastal plains, each influencing the type of farming practiced in the region. The district's soil is classified into four distinct categories: rice, garden, alluvial rabi, and upland warkas. While the upland warkas soil is of lower quality, it still yields cereals like nachni (ragi millet), vari (barnyard millet), and harik (kodo millet), though in smaller amounts. The area's varied topography and soil characteristics also support a range of pulses, including wal (field beans), chawali (black eyed peas), tur (pigeon pea), gram (chickpea), moong (legume), and udid (black gram), particularly during the rabi season.

Ratnagiri's agricultural landscape has remained consistent over the years, with the British gazetteer of 1880 describing the main crops during the 19th century to be nachni (ragi millet), harik (kodo millet), vari (barnyard millet), and rice. Today, these staples, along with ragi, continue to be cultivated in the district. In addition to this, Ratnagiri is a district that also produces pulses, oilseeds, spices, fruits, vegetables, and fodder crops.

Ratnagiri's horticulture is rich and diverse, featuring main crops such as mangoes, cashew nuts, coconuts, kokum (garcinia indica), jackfruit, ladyfingers, eggplants, and jambhul (jamun). Recently, farmers have started planting new varieties of Alphonso mangoes, including Sindhu and Ratna. The fertile soil has also facilitated the growth of fruits like peru, chikoo, and pineapples, which are primarily enjoyed at home.

In addition to these horticultural offerings, black gram (udid) is widely cultivated across the district. The region also engages in sugarcane and salt farming, further contributing to its agricultural diversity.

According to the district Gazetteer (1962), the district is predominantly characterized by Konkan laterite rock formations, derived from the original trap geology. This results in a variety of soils, primarily lateritic, which vary in color from bright red to brownish-red. In Ratnagiri, the cropping pattern remains largely traditional.

Most farmers primarily cultivate a single crop (paddy) during the Kharif season. However, some farmers with access to additional water may choose to grow two crops, typically one paddy and another vegetable, or they may opt to cultivate paddy twice.

Agricultural Communities

Locals in Ratnagiri emphasized that the tradition of farming was deeply rooted in their heritage, with life revolving around agricultural practices passed down through generations. The British Gazetteer of 1880 indicated that almost all communities in the district (Brahmins, Marathas, Kunbis, Muslims, Bhandaris, and Mhars) were engaged in agriculture.

The type of farming practiced often correlated with the communities. For instance, Marathas predominantly inhabited the upland villages under the Sahyadri hills, while Bhandaris and Muslims tended to reside in the lowland coastal areas. Brahmins were generally found in coastal villages and central parts of the district, but were seldom seen near the Sahyadri hills.

Earlier in the 19th century, most of the land was owned by Khots (landowners) who were usually Chitpavan Brahmins. They also had many peasants as workers who tilled the land and carried out other activities. Nonetheless, this system was extremely oppressive and affected peasants' economic and social status. Forcing them to migrate to cities such as Mumbai and Pune (predominantly Mumbai) to work in the Cotton Mills.

In contemporary times, agricultural labor constitutes locals belonging to the Katkari community, who usually migrate from one village to another to find work.

Festivals or Rituals Related to Farming

Rituals during Perni

The Perni phase is a vital period in the agricultural calendar of Ratnagiri, signifying the time when farmers scatter paddy seeds in their freshly plowed fields. A notable tradition during this phase involves placing an onion in the container or bag with the paddy seeds. This ritual is rooted in the belief that including an onion will ensure a bountiful crop, reflecting the community's deep connection to agricultural practices and traditional wisdom.

Rituals during Mrug Nakshatra

During Mrug Nakshatra, a week-long ritual is performed to ensure a bountiful crop. The ceremony begins with an offering of five “vidas” (pan for consumption) in the devghar. This involves placing four vidas at the corners of a cloth and one in the center.

On the following Sunday, participants observe an upwas (fast). Next Tuesday, five or seven unmarried young girls from the village, known as savasani, are invited to the home. The savasnis are honored with a poojan and served vegetarian food, having fasted for half a day beforehand.

The rituals culminate the next day at the Gavdevi mandir, where a Bali (sacrifice) is offered to the devi. This act, known as “Rakhan”, is performed to seek the devi’s protection over the crops and the farmers, ensuring a successful harvest.

Types of Farming

Step Farming | Farming in Hilly Regions

In the hilly regions, step farming is practiced to make efficient use of the abundant water that flows downhill. As conventional farming techniques are unsuitable in hilly regions, this method proves to be effective. Flat areas are carved into the hillside to create steps or terraces, enabling better land use and enhanced water retention.

In the hills of Ratnagiri, each field on a farm is separated by a ‘bandh,’ which includes an opening that allows excess water to flow into the next field, ensuring that all fields receive adequate irrigation.

In areas where step farming isn't possible, the bandh system is still utilized. Here, the natural flow of water is managed by creating openings in each bandh, allowing excess water to overflow into adjacent fields. This method has proven effective due to the heavy rainfall the district receives. Horticultural crops are also periodically irrigated through pipes to maintain optimal growth conditions. Horticulture crops are watered through pipes from time to time.

Mango Picking

Out of all the regions in India, Ratnagiri is particularly famed for its hapus, where the unique climate and fertile soil create the ideal conditions for this exquisite fruit. Historically, the Alphonso mango was first cultivated in the lush Konkan region of Maharashtra, along India’s western coast, where it has thrived for centuries. Legend has it that the first Alphonso tree was planted by the Portuguese in Vengurla in the early 1500s. The variety is named after Alfonso de Albuquerque, the 1st Duke of Goa (1453-1515). The now world-famous mango variety received a Geographical Indication (GI) tag on October 5, 2018. This tag was granted to Alphonso mangoes from five districts of Maharashtra, which include Ratnagiri.

The region is home to two varieties of mango trees: Kalami and Raivali. Kalami mangoes come from grafted trees (the word Kalam means "to graft" in Marathi) and are typically eaten fresh or sold in markets. In contrast, Raivali mangoes grow wild and are commonly used in traditional preparations such as Aambyache Sath/Aam Poli (a sun-dried sweet delicacy) and Aamsal (sun-dried raw mango skin), among other mango-based food items.

The Alphonso mango, celebrated for its sweetness and richness, has a fascinating history that intertwines with the legacy of Alfonso de Albuquerque, a Portuguese explorer who introduced the fruit to India. Albuquerque, known for his conquests in Goa and the establishment of a vast maritime empire, is the namesake behind this beloved variety.

The process of how luscious mangoes make their way from the orchard to the dining table is an intricate one. The journey is a delicate blend of tradition, skill, and precision, all aimed at ensuring the quality and flavor of the fruit are preserved.

Mangoes are typically harvested between March and June, with the peak season occurring in April and May. To gather the ripened fruit, farmers rely on a traditional tool known as the Jhela, which plays a crucial role during the harvesting process.

The Jhela is a bamboo tool specifically designed for efficient mango picking. It consists of a long bamboo pole with smaller bamboo sticks attached to form a scoop. This scoop gently detaches the mango from the branch, allowing the fruit to fall into a gunny bag securely tied to the bamboo pole. This method ensures that mangoes are not bruised or damaged, allowing only the best fruit to be harvested.

The Jhela is an essential tool during harvest season. The bamboo implement has become a trusted companion for farmers, facilitating the delicate task of picking mangoes from high branches without causing harm to the fruit.

During the harvest season, Ratnagiri becomes a bustling hub as families and communities come together to pick mangoes, celebrating the bounty of their orchards. The careful, traditional methods employed not only ensure the quality of the fruit but also reflect the cultural significance of mango cultivation in the region.

Traditional Agricultural Practices

Sheti in Ratnagiri: A Seasonal Journey

Sheti, in Ratnagiri, beautifully reflects the connection between agriculture and the changing seasons. Each season brings unique practices and terminology, unfolding through eight distinct phases: Bhajavni, First Nangarni, Perni, Phodni, Kadhni, Second Nangarni, Lavni, and Bhat Kapni. These phases are essential for nurturing the land and optimizing crop growth, demonstrating the deep-rooted wisdom of the local farmers who have honed their craft over generations.

The journey begins with Bhajavni in April-May, where controlled fires are lit to eliminate weeds and pathogens, preparing the soil for planting.

Just before the monsoon arrives in early June, farmers engage in the First Nangarni, where a small quadrant of the field is plowed by hand, bulls, or a small tractor, setting the stage for the upcoming planting season.

By mid-June, the process of Perni takes place, involving the scattering of paddy seeds across the plowed area, ideally timed with the Rohini Nakshatra or shortly after the first rains. Following this, Phodni involves the gentle breaking down of mud mounds in the soil, ensuring the seeds find their cozy home. The word "phodni" itself echoes this act; in Marathi, phoda means "to break down," capturing the essence of this nurturing phase.

As the paddy plants rise to about a foot in height, the farmers tenderly uproot them during Kadhni, setting them aside for the next chapter. The term Kadhni resonates with care: kadha means "to take out" in Marathi, reflecting the intimate relationship farmers have with their crops.

This is followed by the Second Nangarni, where the muddy fields, now enriched by the rains, are plowed again in preparation for the next sowing.

As mid to late July approaches, Lavni occurs, where immature paddy plants are grouped in clusters of 2-3 and transplanted into the soil, spaced 15-30 cm apart. Finally, in October, the Bhat Kapni stage arrives, when mature paddy plants, about 4 feet tall, are harvested and arranged into hut-like structures called Pendhe, just before Dussehra and Diwali.

After this threshing, which is locally known as "Jodhni", literally means "to beat", is done. The process involves the use of a quadrant structure called "Machli", which is made up of big red stones called Chira and long sticks. The harvested paddy is threshed on the sticks and is later gathered for further processes such as shelling (done with the help of large Rice shelling machines) and polishing.

The threshed plant, on the other hand, is known as Pendha and is stacked in a semi-conical hut-like structure called Udvi on the Machli that was used for threshing (to avoid contact with the ground). This threshed plant is later on used as fodder for cattle.

Use of Technology

Farmers in Ratnagiri have begun adopting modern technologies such as small tractors and, in some areas, greenhouses. They also utilize contemporary inputs like pesticides and insecticides to enhance productivity. However, since rice, the primary food crop, is often grown for reasons such as subsistence or continuity of generational practices, many still prefer using traditional tools and methods.

In most villages, now small tractors play a crucial role. Farmers who own tractors often lend them to neighbors, with payment typically made in cash or through labor exchanges, as not every farmer has access to this equipment. In the absence of tractors, farmers continue to work their fields manually, preserving their connection to traditional agricultural practices.

Institutional Infrastructure

The establishment of industrial zones, such as the Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporations (MIDCs), has led many residents to shift away from traditional farming. This industrialization has also introduced pollution that affects local fisheries and has driven wildlife, such as monkeys, into agricultural areas.

In Talukas like Chiplun and Ratnagiri, many farmers are increasingly neglecting their agricultural land in favor of jobs in industry. Additionally, mango farmers face significant challenges, including pest attacks from monkeys and rats. The mohar (flower) of the mango tree is particularly sensitive, with even slight disturbances causing it to fall. Unseasonal rains further exacerbate issues related to farming.

Mango farmers also contend with market challenges, particularly regarding the authenticity of their produce. There is growing competition from similar varieties of Alphonso mangoes from Karnataka, which are often sold as Ratnagiri-Sindhudurg Alphonso in major markets such as Navi Mumbai, Mumbai, and Pune.

Another hurdle is the difficulty in securing labor at critical times, which poses a challenge for farmers looking to expand their cultivation.

Market Structure: APMCs

In Ratnagiri, farmers primarily sell their horticultural crops locally or in larger markets located in Mumbai, Navi Mumbai, and Pune. To support these agricultural activities, there are three government warehouses situated in Dhanawadewadi, Lote-Parshuram, and Mirjole, providing essential storage and distribution services.

List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

|

Sr. No |

Name |

Est. Year |

Chairman |

No. of Godowns |

|

1 |

Nachane (Ratnagiri) |

1985 |

NA |

1 |

The concept of Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMC) does not have a strong presence in the district, with only one APMC market available in Nachane, Ratnagiri, which was established in the 1980s. This market serves as a centralized hub for products like Eggs, Chicken, Cashew nuts, Betel nuts, Fish, Bamboo, and Firewood.

Farmers Issues

Awareness of government schemes varies significantly from village to village in Ratnagiri, largely influenced by the involvement of local Gram Panchayats. While some villages actively embrace and implement a wide range of schemes, others may choose not to participate.

Producers of cashew nuts and other crops often operate on a small scale and lack organization, indicating a limited awareness of available government schemes and subsidies. This knowledge gap restricts their access to opportunities that could enhance their productivity and income.

Climate Change and Its Impact on Agriculture in Ratnagiri

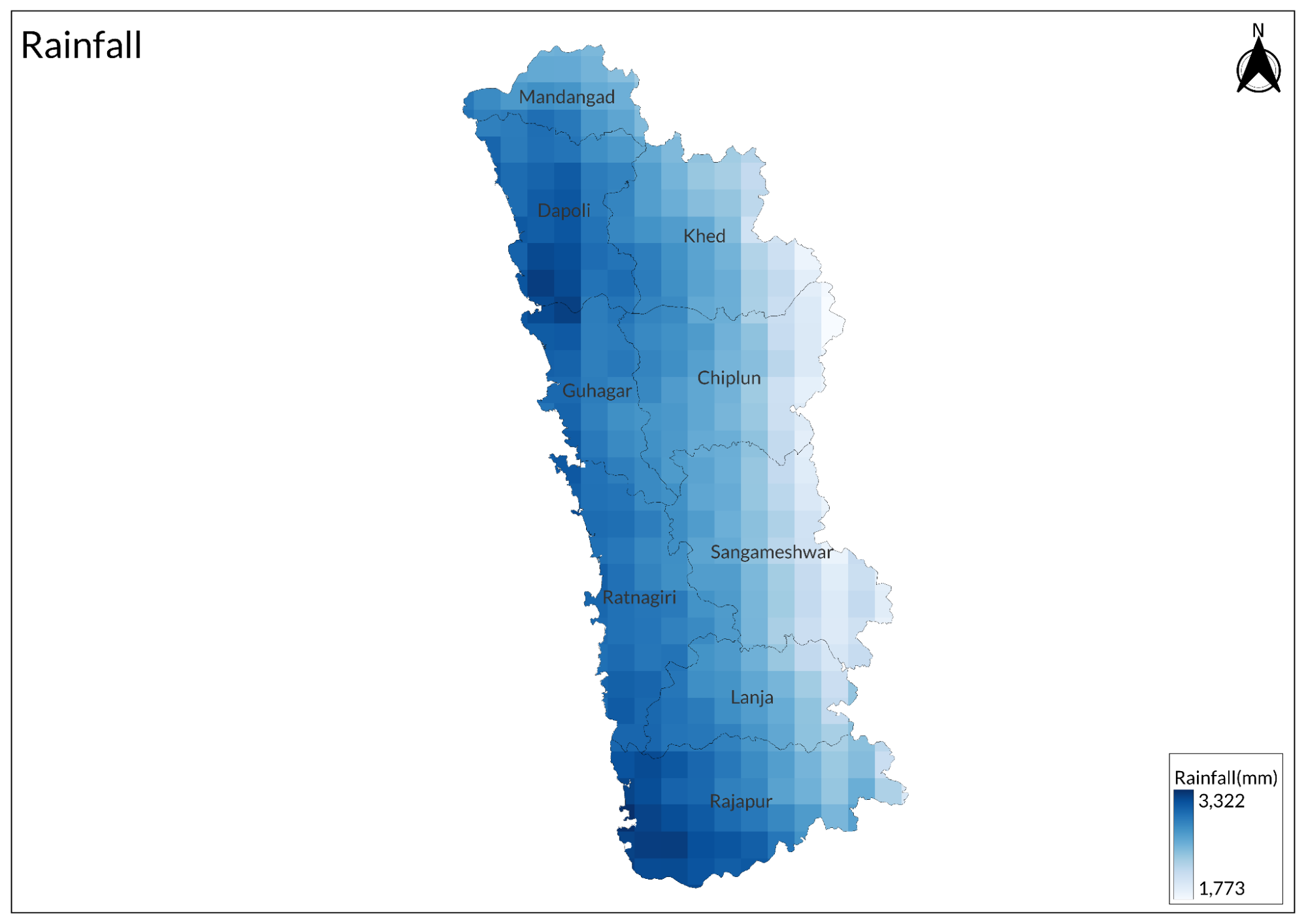

Climate change is reshaping agricultural landscapes globally, and Ratnagiri, nestled in the Konkan region of Maharashtra, is also particularly vulnerable to these shifts. Known for its diverse agricultural produce, Ratnagiri also faces mounting challenges from altered climate patterns that affect rainfall, temperature, and water availability.

A study by Pawar Bhagwan (2024) on the impact of climate change on farming in Dapoli highlights that, in recent years, both minimum and maximum temperatures in Ratnagiri have shown a significant upward trend. Minimum temperatures have been increasing by about 0.05°C per year. This warming can stress crops and change their growing conditions. The minimum relative humidity has been rising, which can affect plant transpiration and the overall water balance in the soil. This means crops may require different water management practices.

Ratnagiri typically benefits from substantial monsoon rainfall. However, data indicate a slight decline in both total rainfall and the number of rainy days from 1980 to 2009, a trend that has continued in recent years. Although overall rainfall levels have remained stable, changes in temperature and humidity impact the timing and distribution of rainfall. For instance, a 1°C increase in minimum temperature can lead to a decrease in rainfall by about 12.3 mm. This variability complicates farmers’ efforts to plan planting and harvesting schedules.

This variability can make it difficult for farmers to plan planting and harvesting. The study also indicates how reductions in potential evapotranspiration (ETm), a measure of how much water is lost through evaporation and plant transpiration, can dramatically reduce crop yields. Banana is a perennial crop in the region, and its yield is also affected by changes in ETm.

In addition to these challenges, Ratnagiri is grappling with coastal erosion and rising salinity levels. Over the past few decades, the coastline has eroded significantly due to rising sea levels, which have increased by 5-6 cm since 1978. This erosion transforms the landscape, pushing the sea further inland and threatening once-fertile agricultural lands.

Ratnagiri’s Monkey Menace

A unique and pressing issue in Ratnagiri is the rising population of monkeys, especially the Tarai gray langur. These primates have become notorious for their destructive feeding habits, damaging fruit and vegetable crops and leading to financial losses that can reach crores. Reports from 2010 highlight the scale of the problem, with farmers bearing the brunt of these losses.

To combat this growing menace, the Ratnagiri Zilla Parishad allocated ₹50 lakh in 2011 to establish over 50 specialized squads aimed at trapping and relocating monkeys to designated forest areas. However, despite these interventions, farmers continue to struggle with the persistent threat posed by these animals.

The underlying problem is linked to rapid infrastructure development. As industrial zones expand, natural habitats are disrupted, driving monkeys into agricultural lands in search of food. This growing conflict leaves farmers in Ratnagiri navigating a complex web of market pressures and wildlife threats, highlighting the urgent need for sustainable solutions to protect both the ecosystem and the farmers’ livelihoods.

A study by Mohan Upadhyay, cited in an IndiaSpend article (2023), reveals that villages like Velas and Bhankot are experiencing severe saltwater intrusion, making traditional farming increasingly difficult. As seawater floods fields, many are turning into mangrove forests that thrive in saline conditions. This change compromises soil quality for traditional crops like paddy and poses a threat to local ecosystems.

The changes in the coastal ecosystem also impact local wildlife. For instance, Olive Ridley turtles, which use the beaches for nesting, are affected by changing shoreline conditions. High tides are now reaching closer to the nesting sites, often washing away eggs or preventing turtles from nesting altogether.

The encroachment of mangroves and saltwater intrusion is making it harder for locals to sustain their livelihoods through farming and grazing. In response, some farmers are considering alternative crops, such as coconuts, which can tolerate saline conditions. However, transitioning to these new crops requires a long-term investment.

Graphs

Irrigation

Cropping Metrics

Land Use and Credit

Sources

Flavia Lopes. 2023. Against The Sea: Rising Sea Levels In Ratnagiri Turn Farm Lands Into Mangrove Forests. India Spend.https://www.indiaspend.com/indias-climate-ch…

Gazetteers Department. 1880. District Gazetteers, Ratnagiri-Savantwadi District. Agriculture, Caste, Rainfall, and Soils. Government of Maharashtra.https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015…

Gazetteers Department. 1962. District Gazetteers, Ratnagiri District. Government of Maharashtra.https://gazetteers.maharashtra.gov.in/cultur…

Kokan Development Staff. The History and Origin of Alphonso Mango: A Fruit with a Royal Pedigree. Kokan Development.https://kokandevelopment.com/the-history-and…

KrishKosh Granth https://krishikosh.egranth.ac.in/items/e6ac1…

Mr. Pawar Sunil Bhagwan. 2024. TO STUDY THE CLIMATE CHANGE AND ITS IMPACT ON PRECIPITATION AND PRODUCTIVITY: A CASE STUDY OF DAPOLI TEHSIL. DIST. RATNAGIRI. COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY DR. BALASAHEB SAWANT KONKAN KRISHI VIDYAPEETH.

Msamb. Comhttps://www.msamb.com/ApmcDetail/Profile

Neha Madhukar Deodhar. 2023. Against The Sea: Rising Sea Levels in Ratnagiri Turn Farm Lands Into Mangrove Forests. India Spend.https://www.indiaspend.com/indias-climate-ch…

Patel Kunj M, Effects of Bombay cotton mill industry on Ratnagiri’s rural population, 1961, University of Mumbai, Department of Sociology.http://hdl.handle.net/10603/532914

Sadaguru Pandit. 2017. After swine flu, monkey fever grips Maharashtra, 11 dead; don’t ignore that fever and headache. Hindustan Times.https://www.hindustantimes.com/mumbai-news/a…

Sonar, R. B. 2014. Observed trends and variations in rainfall events over Ratnagiri (Maharashtra) during the southwest monsoon season. MAUSAM, vol. 65, no. 2. MAUSAM Journal.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289…

Staff Reporter. The Story of Alphonso Mangoes. Peepul Tree.https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindi…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.