Contents

- Physical Features

- Climate

- Geology

- Soil

- Minerals

- Rivers

- Krishna

- Tributaries

- Snakes

- Crustaceans (Crabs)

- Gubernatoriana alcocki

- Land Use

- Environmental Concerns

- Deforestation/Urban development

- Water Pollution

- Water Scarcity

- Conservation Efforts/Protests

- Chikhli Village Protest

- Karad Airport Expansion Protest

- Forest Agitation

- Environmental NGOs

- Eco-Pro Satara

- Kaas Conservation Group

- Nisarg Mitra Mandal

- Paryavaran Sanvardhan Samiti, Satara

- Sahyadri Nisarga Mitra (SNM)

- Satara Nature Club

- Watershed Organization Trust (WOTR)

- Graphs

- Water

- A. Rainfall (Yearly)

- B. Rainfall (Monthly)

- C. Evapotranspiration Potential vs Actual Numbers (Yearly)

- D. Annual Runoff

- E. Runoff (Monthly)

- F. Water Deficit (Yearly)

- G. Water Deficit (Monthly)

- H. Soil Moisture (Yearly)

- I. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Bore Wells

- J. Seasonal Groundwater Levels: Dug Wells

- Climate & Atmosphere

- A. Maximum Temperature (Yearly)

- B. Maximum Temperature (Monthly)

- C. Minimum Temperature (Yearly)

- D. Minimum Temperature (Monthly)

- E. Wind Speed (Yearly)

- F. Wind Speed (Monthly)

- G. Relative Humidity

- Human Footprint

- A. Nighttime Lights

- Sources

SATARA

Environment

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Satara, situated in the Western Ghats, recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is renowned for its rich biodiversity and stunning landscapes, including the Kaas Plateau, often referred to as the "Valley of Flowers." The region is traversed by significant rivers like the Krishna and Koyna, which nourish its fertile plains and dense forests.

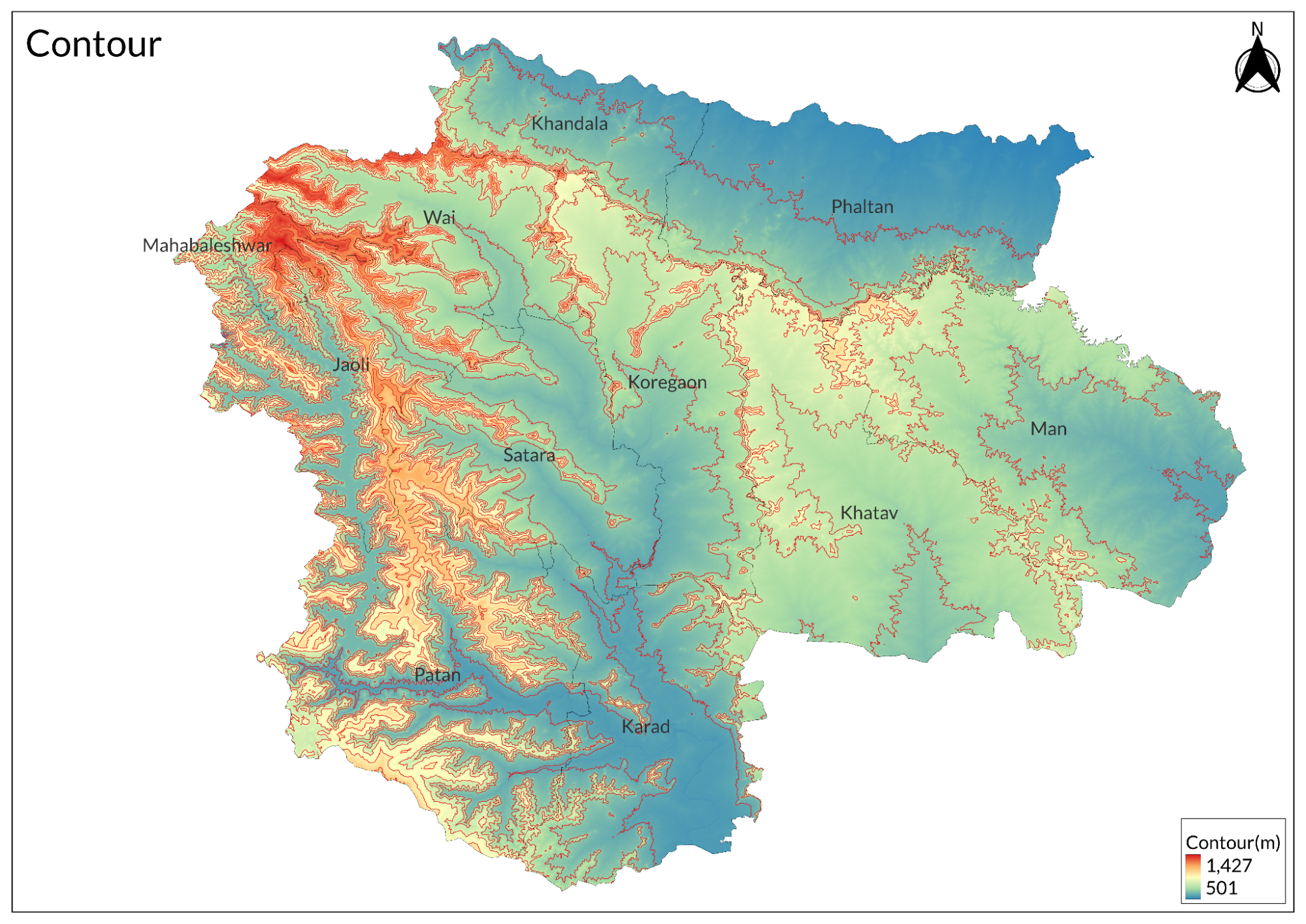

Physical Features

The district of Satara is located in the western part of Maharashtra, India. It spans an area of 10,480 square kilometers and is situated at an average elevation of approximately 677 meters above mean sea level. The name "Satara" derives from the seventeen towers and walls of the fort Ajinkyatara, which encircle the district's headquarters in the city of Satara.

Satara is bordered by several districts: the Bhima River lies to the north, separating it from Pune district; Solapur district is to the east; Sangli district to the south; and Ratnagiri district to the west, with Raigad district located to its northwest. The district is divided into 11 tehsils, which include notable towns such as Mahabaleshwar, Panchgani, and Karad.

The district features two primary hill systems: the Sahyadri Range and the Mahadev Range. The Sahyadri system runs along the western boundary of Satara for about 96 kilometers, characterized by dense forests and high hills, which historically provided strategic advantages for fortifications during the reign of Shivaji Maharaj, who constructed around 25 forts in this region. The landscape includes 56 notable hills and numerous forts distributed across its subdivisions. The Mahadev Range begins north of Mahabaleshwar and extends southeast across Satara, featuring significant forts such as Gherakelanja, Tathvada, and Varugad. This range has three major spurs: Chandan-Vandan, Vardhangad-Machindragad, and Mahimangad-Panhala.

Mahabaleshwar, at an elevation of 1,438 meters, is the highest point in the Mahadev Hill system and is renowned as a hill station known for its scenic beauty and historical significance. Other notable hill stations in Satara include Panchgani (1,293 m) and Khandala (622 m).

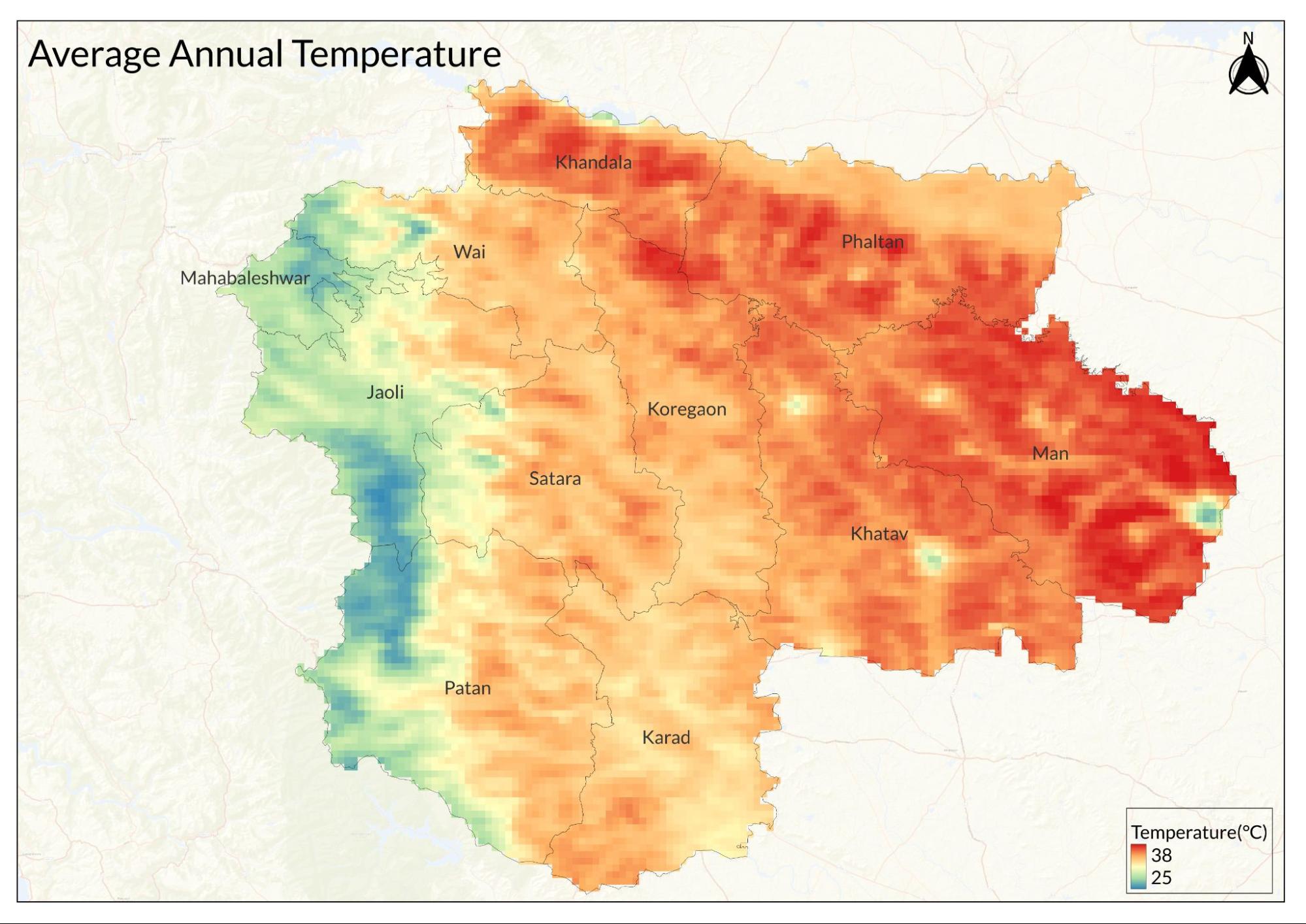

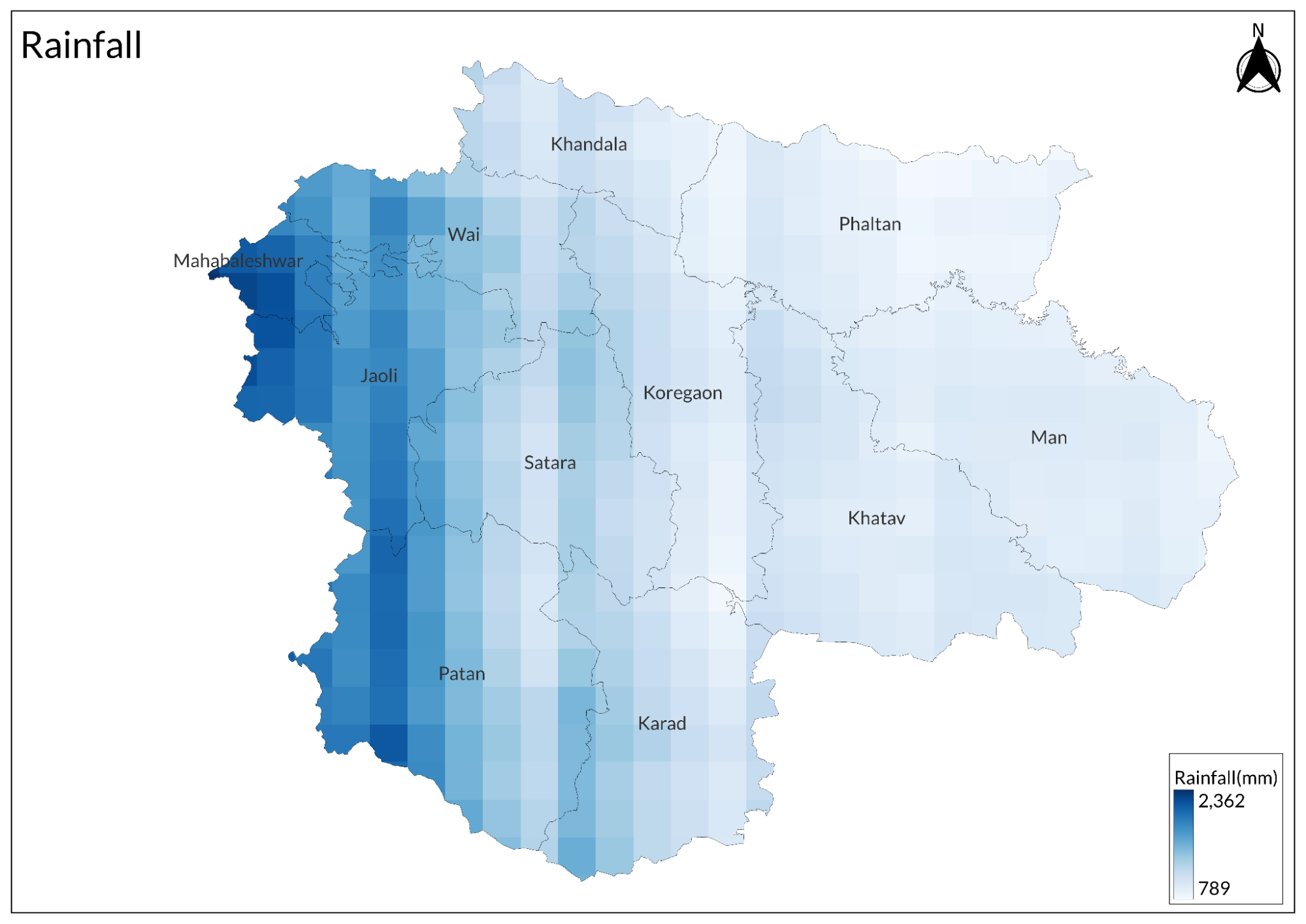

Climate

Satara city has a tropical wet and dry climate, shaped by its high altitude and the surrounding mountains. Summers are quite hot, with temperatures reaching up to 42.1 °C (107.8 °F) in April and May, while the average maximum temperature throughout the year is around 31.2 °C (88.2 °F). In contrast, winter temperatures can drop to a minimum of 12.8 °C (55.0 °F) in January, with record lows falling to 4.8 °C (40.6 °F).

The city receives between 900 mm and 1,500 mm of rainfall annually, with June and July being the wettest months, averaging about 199.7 mm (7.86 inches) and 224.9 mm (8.85 inches), respectively. Humidity is generally high, averaging around 70.3%, and can reach up to 79% during the monsoon season, while January and February tend to be drier.

Geology

The district is characterized by horizontally layered basaltic lava flows from the Deccan Trap, which were formed by fissure-type volcanic eruptions that occurred between the Upper Cretaceous and Lower Eocene periods, approximately 65 million years ago. The lower sections of these basaltic flows are fine-grained, compact, and grayish-black in color, while the upper sections are vesicular. The thickness of the individual lava flows varies significantly, ranging from a few meters to as much as 40 meters. Additionally, laterite capping is found on nearly all the plateaus of the Western Ghats, as well as in the northern and central regions of the district.

Soil

The soils of the district can be categorized into three main types: (i) medium black to deep black soils found on the plains, (ii) lighter soils located on slopes and in the eastern part of the district, and (iii) laterite soils present in the hilly regions on the western side and on small hillocks in the east. Crop cultivation is carried out based on the specific type of soil.

Minerals

Bauxite ore is the only mineral found in the district.

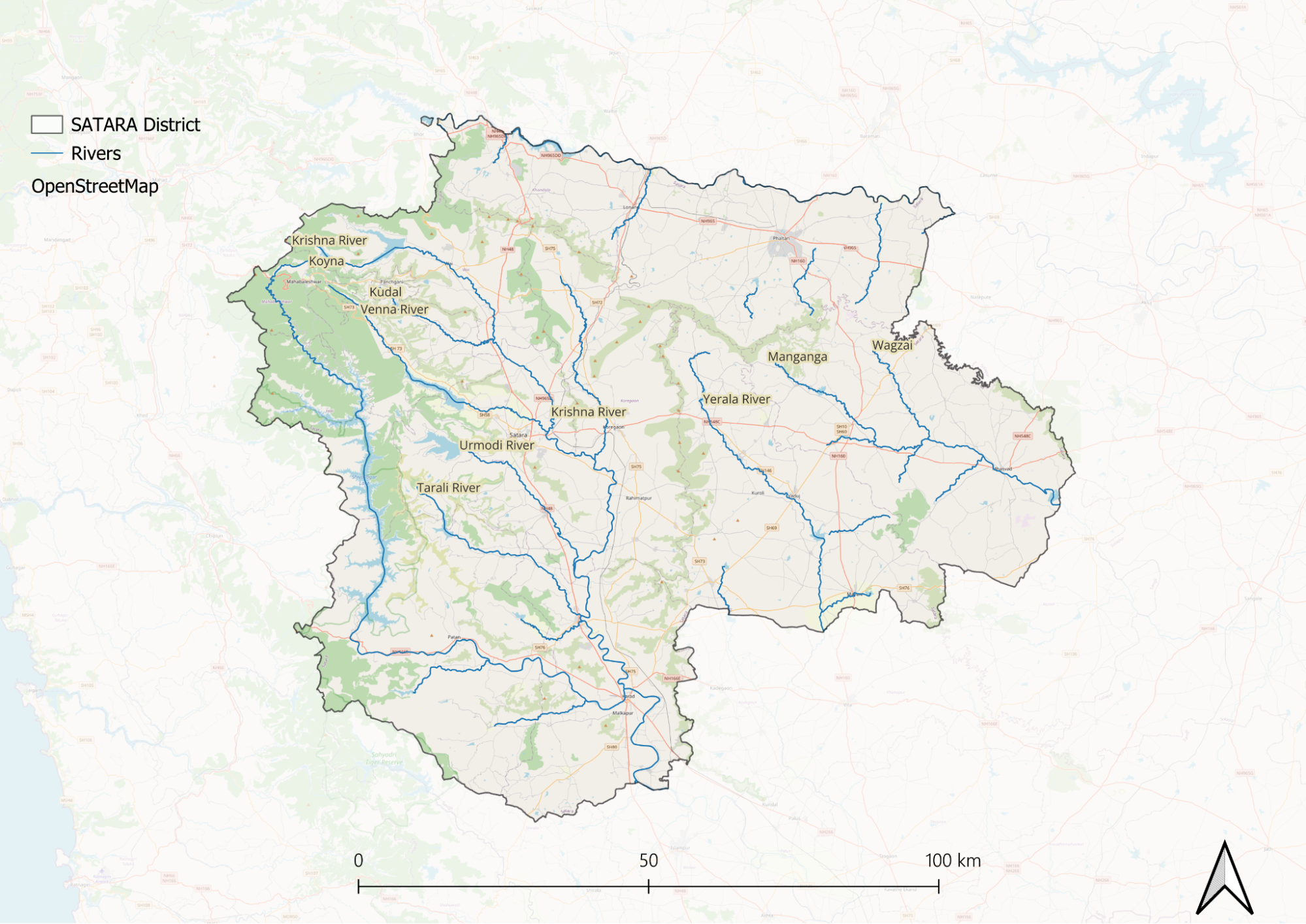

Rivers

There are two major river systems in the district: the Bhima system, which covers a small part in the north and northeast, and the Krishna system, which spans the rest of the district.

The Bhima river and its tributaries include the Nira and the Man. A narrow belt beyond the Mahadev hills drains north into the Nira, which flows east into the Bhima. In the northeast corner of the district, beyond the Mahimangad-Panhala spur, drainage flows southeast along the Man, which later flows east and northeast to join the Bhima. The total area of the Bhima system, including part of Wai and the entire Phaltan and Man, is estimated to be about 177 km. The Krishna drainage system includes, besides the central stream, the drainage of six feeders from the right side: Kudali, Yenna, Urmodi, Tarli, Koyna, and Varna, and two from the left side: Vasna and Yerla.

Krishna

The Krishna is one of the three major rivers of Southern India. Like the Godavari and Kaveri, it flows across almost the entire breadth of the Country from west to east and empties into the Bay of Bengal. It is shorter in length compared to the Godavari, but its drainage area includes that of its two major tributaries, the Bhima and Tungbhadra. The river spans approximately 1287 km in length, with about 241 km within Satara limits.

Krishna originates on the eastern edge of the Mahabaleshwar plateau, four miles west of the village of Jor in the extreme west of Wai. The source of the river lies at approximately 1,371 m above sea level on the Mahabaleshwar hill plateau, and stands an ancient temple of Mahadev. Inside the temple is a small reservoir into which a stream flows out of a stone cow-mouth.

From its source, the Krishna flows east for about 24 km until it reaches the town of Wai. From Wai, the river's course turns south. Approximately 16 km from Wai, it receives the Kudali from the right, about two miles south of Panchvad in South Wai. After meeting the Kudali, the river continues south through the Satara subdivision, passing Nimb and Varuth. After 24 km, it receives the Venna on the right, near Mahuli.

After meeting the Yenna, the Krishna curves southeast, marking the boundary between Satara and Koregaon for about 16 km until it reaches the outskirts of Karad. In Koregaon, after a 64 km course, the Krishna receives the Vasna from the left, and in the extreme south of the Satara subdivision, about two miles southwest of Vanegaon, it receives the Urmodi from the right.

In Karad, the river flows almost due south. It receives two tributaries from the right: the Tarli near Umbraj after a journey of about 104 km, and the Koyna near Karad. From Karad, the Krishna flows southeast through Valva and Bhilavdi in Tasgaon. In the south of Bhilavdi, it receives the Yerla from the left, after a journey of 193 km, and about a few km south of Sangli, in the extreme south of the district, it receives the Varna from the right. After joining with the Varna, the Krishna continues its southeastward course toward Belgaum within Satara limits.

In the northwest, particularly in Wai and Satara, and in the south, in Karad, Valva, and Tasgaon, crops such as sugarcane, groundnuts, chilies, and wheat are grown through irrigation.

Tributaries

Kudali: The Kudali, a minor tributary of the Krishna in the north, rises near Kedamb in Javli. After a southeastward journey of approximately sixteen miles through Javli and Wai, flanked by the Vairatgad range to the left (north) and the Hatgegad-Arle range to the right (south), it joins the Krishna from the right about two miles south of Panchvad in Wai.

Venna: The Venna, one of the Krishna's principal tributaries, originates on the Mahabaleshwar plateau and flows into the Yenna valley below the Lingmalla bungalow and plantation, on the eastern edge of the Mahabaleshwar hills, about three miles east of Malcolmpeth. It traverses the valley between the Hatgegad-Arle range on the left (north) and the Satara range on the right (south). After a southeasterly journey of about forty miles through Javli and Satara, it empties into the Krishna at Mahuli, approximately three miles east of Satara. In the dry season, the flow of the stream diminishes, leaving water in pools. It is crossed by several bridges: a footbridge at Medha in Javli and four road bridges.

Urmodi: The Urmodi, a minor tributary of Krishna, rises near Kas in Javli. It flows southeast through a valley flanked by the Satara range on the left (north) and the Kalvali-Sonapur range on the right (south). After a southeastward journey of about twenty miles, mostly through Satara, it empties into the Krishna about two miles southwest of Vanegaon in the extreme south of the Satara subdivision.

Tarli: The Tarli, a minor tributary of the Krishna, originates in the northwest of Patan, approximately ten miles above the village of Tarli. It flows southeast through a valley flanked by the Kalvali-Sonapur range to the left (northeast) and the Jalu-Vasantgad range to the right (southwest). After a southeastward journey of about twenty-two miles through Patan and Karad, it joins the Krishna from the right at Umbraj in Karad.

Koyna: The Koyna, the largest of Krishna's tributaries in Satara, originates on the western side of the Mahabaleshwar plateau near Elphinstone Point. It drains a course of 129 km within Satara limits.

Snakes

The district is home to a variety of snake species, which are categorized into two main groups. The non-poisonous snakes include the kadu, a small snake resembling an earthworm; Uropeltid species, which are purplish-green with yellow specks and often found under bushes; dhaman, a quick-moving yellowish snake sometimes mistaken for a cobra; harantol or sarptol, typically located in forested areas; and mandol. In contrast, the poisonous snakes consist of nag, manyar, raat, ghonas, phoorsa (a sidewinding snake), and an olive-green pit viper found in hilly bamboo regions.

Crustaceans (Crabs)

Gubernatoriana alcocki

Ghatiana alcocki was first discovered in 2014 in the Satara district of Maharashtra, where it was found beneath small rocks in short-lived, seasonal streams on a mountain plateau. This species is highly specialized, thriving exclusively at high altitudes—at least 1,000 meters above sea level—within the Western Ghats. Its restricted range is largely due to its preference for elevated, isolated habitats, which naturally limit its distribution.

One of the most intriguing aspects of G. alcocki is its unusual ecological relationship with the Bombay swamp eel (Monopterus indicus). This predator–prey interaction is bidirectional: while adult eels feed on the crabs, the crabs prey on juvenile eels, creating a complex dynamic within their shared habitat. The crabs are most commonly observed during the monsoon season (June to September) but are also relatively abundant during the dry months, indicating a high level of adaptability.

In terms of appearance, G. alcocki is olive-brown, with orange-brown, hairy appendages. The pincers exhibit sexual dimorphism: in females, both pincers are nearly equal in size, with the claw fingers bearing 12–14 small, blunt teeth, leaving only a narrow gap when closed. In males, however, the right pincer is significantly larger and smoother, with only two or three large teeth and a wide gap between the fingers, likely aiding in food handling or mate competition.

The species is named in honor of Alfred William Alcock, an Indian-born British naturalist renowned for his work on decapod crustaceans (ten-legged species such as crabs and lobsters). Alcock also played a pivotal role in advocating for the creation of the Zoological Survey of India, making this tribute especially fitting.

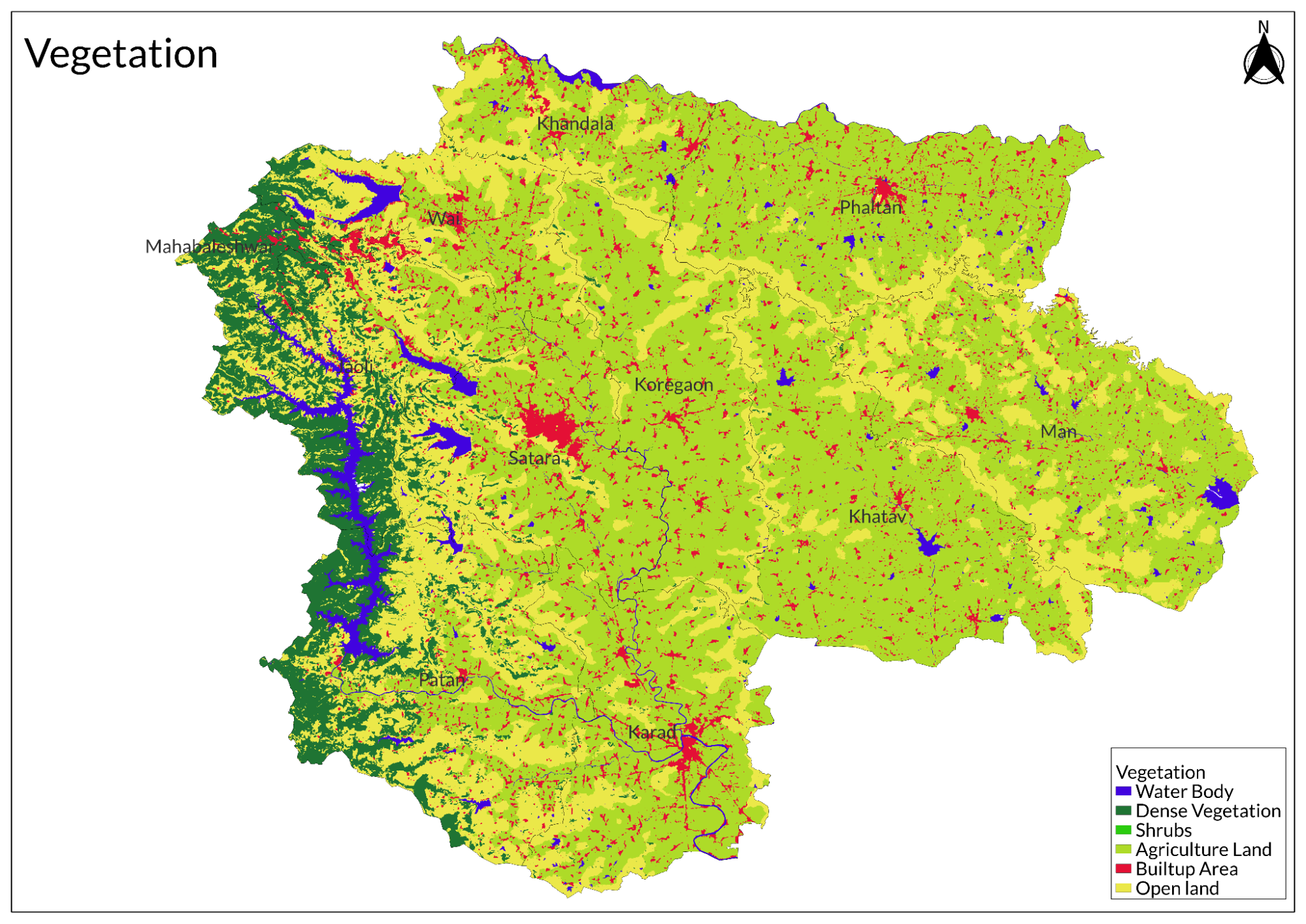

Land Use

Environmental Concerns

Deforestation/Urban development

GSI experts report that deforestation in Satara, Maharashtra has significantly increased landslide frequency, with agricultural expansion and urban development on hill slopes weakening the Western Ghats' stability, particularly evident during heavy rainfall events like those causing recent devastating landslides in Taliye village; the loss of forest cover has disrupted natural slope stability that historically prevented such disasters, as past settlements were limited and didn't encroach upon forests that served as erosion barriers, whereas decades of rapid urbanization and agricultural activities have led to extensive encroachment creating communities unaware of geological risks; to mitigate these issues, experts recommend educational initiatives about human-induced geographical changes and comprehensive studies identifying high-risk zones, with current mapping showing approximately 5% of western Maharashtra as highly landslide-prone and an additional 30% at moderate risk.

Water Pollution

Water pollution in Satara district, Maharashtra, is a pressing concern, particularly affecting the Krishna River and the local drinking water supply. The Krishna River suffers from significant contamination due to industrial effluents, especially from sugar factories, as well as municipal wastewater discharged from towns like Wai, Satara, and Karad. As the river flows towards these urban areas, its water quality deteriorates, marked by increased levels of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), suspended solids, and turbidity. The drinking water supply in Satara city is also at risk, with contamination occurring during distribution. The presence of faecal coliforms and nitrites in the water poses serious health risks, potentially leading to waterborne diseases such as cholera, diarrhea, dysentery, hepatitis A, typhoid, and polio.

Water Scarcity

Water scarcity is a critical issue in Satara district, Maharashtra, aggravated by insufficient rainfall during the latest monsoon season. The situation has deteriorated to the point where Section 144 has been imposed in both Satara and neighboring Sangli districts to combat water theft and regulate the transportation of cattle fodder. This measure reflects the severity of the crisis, as many lakes and ponds have dried up, and groundwater levels have significantly declined.

The primary water sources for Satara are the dams along the Krishna River and its tributaries, such as the Warna River. However, these reservoirs are currently not filled; for instance, Koyna Dam holds only 37% of its total capacity of 105 TMC, while Chandoli Dam has just 33% of its 34 TMC capacity remaining. As a result, approximately 1,060 hamlets in the district have been left without access to drinking water as of 2024.

In response to this dire situation, local administrations have deployed nearly 250 water tankers to ensure that residents receive potable water. The district collector has indicated that Satara is experiencing moderate drought conditions due to the limited availability of water. Prohibitory orders have been enacted until the end of May to manage and conserve the remaining water resources effectively.

These restrictions specifically target areas along canals reliant on various lift irrigation schemes that supply water for domestic use to about 80% of Sangli district residents. The imposition of Section 144 aims to prevent unauthorized gatherings near these critical water sources, highlighting the urgency of addressing water scarcity in Satara district.

Conservation Efforts/Protests

Chikhli Village Protest

In 2008, residents of Chikhli village opposed the land acquisition by the energy company Suzlon, claiming the company employed deceptive practices to acquire land at prices below market value. The villagers successfully forced the shutdown of 41 wind turbines operated by Suzlon, highlighting their determination to protect their rights and resources.

Karad Airport Expansion Protest

In 2019, small-scale farmers organized protests against the expansion of Karad Airport. They staged a sit-in outside the district's planning administration, advocating for the preservation of fertile and irrigated agricultural land that was at risk due to the proposed development.

Forest Agitation

In addition to these protests, farmers in Satara adopted innovative methods of dissent, such as allowing their livestock to graze in reserved forest areas. This form of protest aimed to draw attention to issues regarding land use and conservation.

Environmental NGOs

Eco-Pro Satara

Focused on ecological restoration and sustainable development, Eco-Pro works on restoring degraded ecosystems in Satara, promotes renewable energy use, and conducts community initiatives aimed at fostering sustainable living practices.

Kaas Conservation Group

Dedicated to the conservation of the Kaas Plateau, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, this group works on preserving its unique biodiversity. They educate visitors about the ecological significance of the plateau and collaborate with local authorities to manage over-tourism effectively.

Nisarg Mitra Mandal

Committed to wildlife protection and environmental awareness, this NGO conducts drives to raise awareness about local wildlife and habitats while organizing clean-up initiatives in natural areas.

Paryavaran Sanvardhan Samiti, Satara

Focused on tree plantation, water conservation, and environmental education, this NGO leads afforestation projects in deforested areas, promotes rainwater harvesting and watershed management practices, and conducts workshops to engage the community in conservation efforts.

Sahyadri Nisarga Mitra (SNM)

This organization is dedicated to conserving biodiversity and wildlife in the Western Ghats. Their initiatives include protecting endangered species such as vultures and the Malabar Giant Squirrel, promoting eco-tourism to raise awareness about conservation, and conducting biodiversity studies and educational programs.

Satara Nature Club

This club aims to increase awareness and preserve the natural environment through activities like trekking and nature camps that educate participants about local ecosystems. They also organize bird-watching sessions and wildlife photography workshops while promoting sustainable tourism in the Kaas Plateau.

Watershed Organization Trust (WOTR)

This organization focuses on watershed management and sustainable agriculture by implementing development projects to restore degraded lands. They promote soil conservation techniques and provide training for farmers on climate-resilient agricultural practices.

Graphs

Water

Climate & Atmosphere

Human Footprint

Sources

Dhekale, P., Nikam, P., Dadas, S., & Patil, C. 2019. Water Quality and Sediment Analysis of Selected Rivers at Satara District, Maharashtra.International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD),3(6), 239–243.https://www.ijtsrd.com/papers/ijtsrd28062.pdf

Dighe, S. 2021, August 1. Encroachment on slopes, deforestation to blame for landslides in Maharashtra: Experts. The Times of India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/pun…

Government of Maharashtra, Water Supply and Sanitation Department. (2025, March 6). Groundwater Surveys and Development Agency.https://gsda.maharashtra.gov.in/english/

Nayak, M. (2024, April 22). Maharashtra water crisis: Section 144 imposed in Sangli, Satara districts to stop water theft - check full list of restrictions. India.Com.https://www.india.com/maharashtra/maharashtr…

Richa Malhotra. 2016. Meet the Western Ghats’ Wonderful New Freshwater Crabs.Science The Wire.https://science.thewire.in/science/meet-the-…

Satara (City). (2025). In Wikipedia.https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=S…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.