Contents

- Crop Cultivation

- Soil Types

- Colonial Experiments & Sindhudurg’s Crop Varieties

- Agricultural Communities

- Festivals/Rituals Related to Farming

- Types of Farming

- Rice Farming

- Nagli Cultivation

- Traditional Agricultural Practices

- Use of Technology

- Market Structure: APMC

- List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

- Farmers Issues

- Graphs

- Irrigation

- A. No. of Projects

- B. No. of Ponds/Vilage Lakes and Storage Dams

- C. Irrigation Beneficiary Area vs Irrigated Area

- D. Share of Beneficiary Area Irrigated

- E. Tubewells and Pumps Installed In The Year

- F. Irrigation and Water Pumping Facilities

- Cropping Metrics

- A. Share in Total Holdings

- B. Cultivated Area (With Components)

- C. Gross Cropped Area (Irrigated + Unirrigated)

- D. Share of Cropped Area Irrigated

- E. Distribution of Chemical Fertilizers

- Land Use and Credit

- A. Area of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- B. Size Groups' Share in Total Agricultural Land Holdings Area

- C. No. of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- D. Size Groups' Share in Total No. of Agricultural Land Holdings

- E. Agricultural Lending

- F. Agricultural Credit as a share of Total Credit

- Sources

SINDHUDURG

Agriculture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Sindhudurg, located along the picturesque Konkan coast, has a long-standing agricultural heritage that forms the backbone of its rural economy. The region is especially famous alongside Ratnagiri for its Alphonso mango, which has earned a Geographical Indication (GI) tag, highlighting its unique taste and quality that have garnered both national and international recognition. The region is known for its diverse cropping patterns, supported by its favorable tropical climate and rich soil. Agriculture has historically been a family-oriented practice, deeply rooted in the local culture, with farming passed down through generations.

Despite the region’s ideal agricultural conditions, significant shifts have occurred over the years. Migration to urban centers has become a growing trend, as many young adults move to cities in search of better economic opportunities. This shift, combined with environmental pressures, has contributed to the abandonment of some farmlands, signaling the broader changes brewing within Sindhudurg’s agricultural landscape.

Crop Cultivation

Sindhudurg district boasts a diverse and rich agricultural landscape shaped by its unique geographical features, climatic conditions, and deep-rooted farming traditions. The region’s topography plays a pivotal role in determining which crops thrive there, and as such, it influences the agricultural choices made by local farmers. The district’s geographical diversity, with its hilly terrain and narrow riverine plains, means that crop cultivation varies significantly across the region.

Soil Types

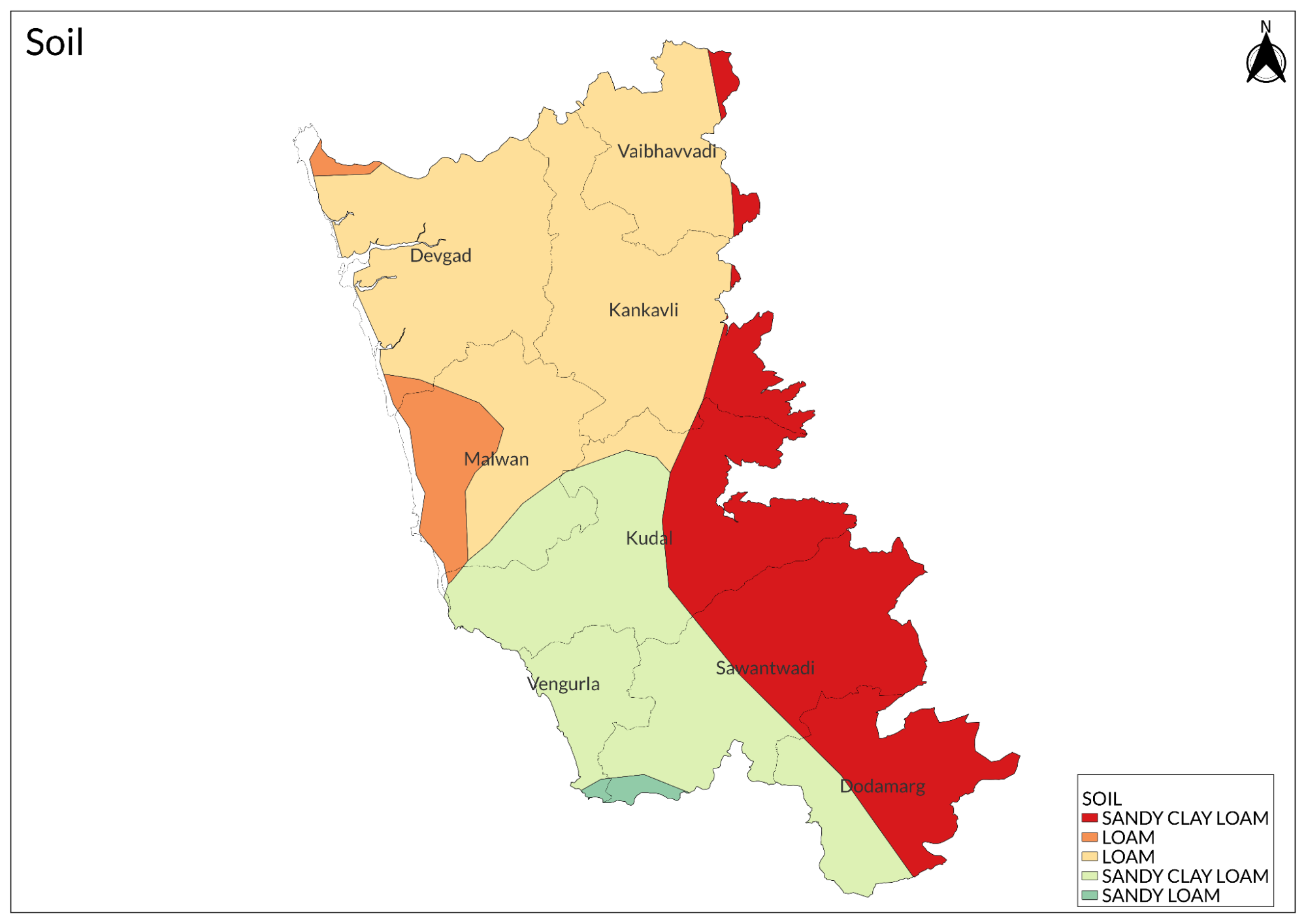

The geographical characteristics of Sindhudurg play a central role in shaping its agricultural practices. The district is predominantly hilly, with about 40-50% of the land classified as hilly terrain, as reported by the Ministry of Water Resources’ Central Ground Water Board.

The region’s varied physiography includes deep valleys in the eastern part, flat-topped hills in the middle, and coastal plains in the west. These diverse topographical features impact the types of crops that can be cultivated in different areas of the district.

The soils in Sindhudurg, mainly derived from lateritic rock, are classified into four broad types: rice soils, garden soils, varkas soils (hill slopes), and alluvial soils. The rice soils are found in the lowlands, making them ideal for paddy cultivation, while the varkas soils, located on hill slopes, are suited for coarser grains and hardy crops. These rice soils are further categorized into Mali, Kuryat, and Panthar, depending on their elevation and proximity to water sources. Mali soils are found in higher elevations, Kuryat soils in the lowlands, and Panthar soils along watercourses, with each type supporting varying degrees of rice cultivation.

Colonial Experiments & Sindhudurg’s Crop Varieties

Rice has historically been the cornerstone of agriculture in Sindhudurg, with past farming practices centered around its cultivation. It appears that the British attempted to diversify the region’s crops, mostly by introducing cash crops, but were unable to do so due to the region’s soil conditions.

The colonial Gazetteer (1880) paints a picture of Sindhudurg's agricultural system as largely subsistence-based, with little potential for commercial farming. It seems the self-sustaining agricultural system of the district could not be easily shaped or commodified by colonial forces. The report mentions that the soil was "chiefly light, and mixed with stone and gravel," making it unsuitable for cultivating a "better class of crops" such as cotton and tobacco. The phrase "better class of crops" appears to refer to cash crops. It’s clear that, at least in the early years of British rule, the region’s agricultural landscape was not conducive to commercial farming.

These conclusions, it seems, were drawn after a series of failed attempts where the British tried to cultivate commercial crops like coffee and hemp. The British, being ever the experimenters and commercial contenders, introduced crops like coffee and hemp in the late 19th century, with mixed results. The Tamboli estate, located near Sawantwadi, was the site of an ambitious coffee plantation experiment in 1878-79.

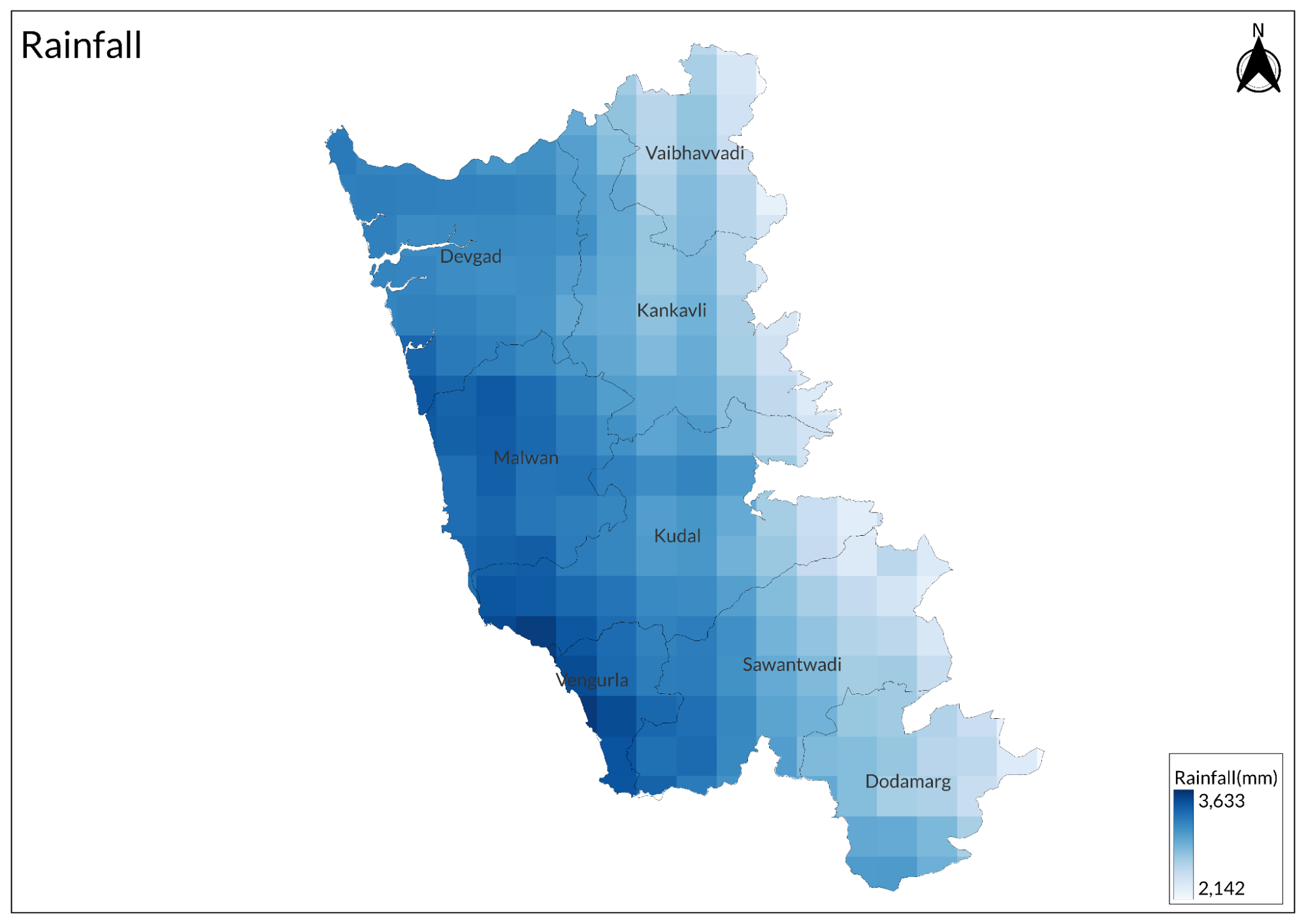

The British attempts to introduce coffee cultivation in Sindhudurg, by importing plants from Kodagu (Coorg), encountered significant challenges due to the region’s climatic conditions. According to the gazetteer, the climate and erratic rainfall patterns proved unsuitable for the successful growth of coffee. Despite the initial efforts, the expenditure on the plantation far exceeded the returns, underlining the difficulties of establishing a viable coffee industry in a region with inconsistent rainfall and a non-ideal agro-climatic environment.

Similarly, the introduction of Manila hemp (a banana species from the Philippines) was another colonial experiment aimed at diversifying the region's agricultural output. While the cultivation of hemp appeared successful, the gazetteer notes that its processing presented significant challenges. A machine imported from New Zealand to clean the hemp fibers caused health issues among the workers, ultimately leading to the abandonment of the experiment. Despite its failures, these colonial experiments serve as a fascinating footnote in the district’s agricultural history, offering a glimpse into the evolution of farming in Sindhudurg’s unique environment.

Today, agriculture in the region revolves around a mix of staple food crops, cash crops, and specialty crops, each suited to the local environment and cultural preferences. According to the 2022 NABARD report, the major crops cultivated during the Kharif (monsoon) season include paddy, Nagli (finger millet), cereals, pulses, and oilseeds. During the Rabi (winter) season, pulses, groundnut, sugarcane, and various vegetables are commonly grown.

Rice remains the cornerstone of Sindhudurg's agricultural identity, though many say that the rise of cash crops like mango, cashew, kokum, and coconut has reshaped the district’s economic landscape. The Hapus mango from the Devgad region has earned a Geographical Indication (GI) tag, marking it as a distinct regional product with rising demand both domestically and internationally. Cashew and coconut, as many say, have also become significant contributors to the district’s economy.

In the past, locals note that crops like Ragi (Nachani) were an integral part of Sindhudurg's local diet and farming practices, primarily cultivated for home consumption and consumed especially during festivals. However, over time, the cultivation of Ragi has dwindled, with rice and wheat now taking precedence in agricultural practices. This shift in crop preference reflects not only changes in local farming practices but also in dietary habits, as many say rice and wheat have increasingly become the staples of everyday meals.

While crops like Betel Nut were once more widely grown, they are now less prevalent compared to the past. Nevertheless, some farmers continue to cultivate wild vegetables like Takla (Cassia Tora), Firangi, Ambada (red sorrel leaves), and Alu (Colocasia), keeping alive traditional food sources in the face of modern agricultural shifts.

Agricultural Communities

Farming has long been the foundation of Sindhudurg district’s economy, with a wide array of communities contributing to its agricultural landscape. Historically, farming was a family-centered affair in the region, with both men and women participating in cultivation. Many locals say that the district’s farming practices have primarily been oriented towards subsistence agriculture, where families grew what they needed to feed themselves, with only a portion of the produce sold or traded.

According to the Gazetteer (1880), the key farming communities in the district included the Gaud Brahmins, Marathas, Bhandaris, native Christians, Muslims, and various other local communities, each playing a distinct role in the cultivation and economy of the region.

The Gaud Brahmins, generally considered to be the “wealthier cultivators”, have traditionally held significant land, with many residing in agricultural areas characterized by orchards of mangoes, jackfruits, and cocoa. Marathas, the largest farming group in Sindhudurg, were said to be spread across various regions, playing a central role in the cultivation of crops like rice, pulses, and vegetables.

The farming lifestyle in Sindhudurg, as outlined in the gazetteer, has long been characterized by a strong sense of community. Wealthier landowners typically employed seasonal laborers during peak farming times, such as sowing and harvesting, while poorer farmers often relied on mutual assistance to manage their land. A well-known tradition, varangula, which involves lending bullocks to neighbors for plowing, demonstrates the spirit of resource-sharing and collective effort.

Even today, many locals emphasize the self-sufficient nature of farming in the region. People work in their fields themselves and seek help from neighbors when needed. Farming, after all, is primarily done to meet basic food needs. The period from March to May, when farming activity slows, marks the off-season in Sindhudurg.

During this time, the weather conditions are perfect for growing certain fruits. Sindhudurg is famously the origin of the Alphonso mango, believed to have been first cultivated in the town of Vengurla in the early 1500s. Additionally, cash crops like cashews and betel nuts, which are important exports, many say, are tended year-round by farmers.

In the non-agricultural seasons, farmers focus on maintaining their cash crops and preparing goods for the year ahead. Many engage in activities like carpentry and broom-making, ensuring that they have the necessary items for their homes and farms throughout the year.

When speaking about communities actively engaged in agricultural labor, many locals point to the Katkari community. As agricultural workers or tenants, they participate in a range of farming activities, adapting their methods according to the land they cultivate. Due to their frequent movement from one place to another, many say that they adjust their farming practices to suit the changing environments they settle in. This mobility perhaps allows them to cultivate different crops based on the specific conditions of the land they occupy at any given time.

Although the lifestyle in Sindhudurg may seem quaint, the life of farmers is not without its challenges. Historically, as noted in the gazetteer, many farmers faced economic uncertainty, often trapped in cycles of debt due to high rents and fluctuating crop yields. While some of these issues persist, today, farmers also face new struggles, including a declining interest among younger generations in taking up agriculture.

Festivals/Rituals Related to Farming

In Sindhudurg, farming is intertwined with various local festivals and rituals that honor agricultural cycles and the natural forces that ensure a fruitful harvest. One such festival is Mirag, celebrated after the harvest season, marking a period of rest before the monsoon arrives. During this time, a special pooja (worship ceremony) is performed where all the farmlands are honored and blessed, seeking good fortune for the upcoming season.

Another important festival is Bailpola, during which bulls (vital for plowing and other farming tasks) are honored. Farmers prepare a special poojan for the bulls, offering them nourishing food as a gesture of gratitude and preparing them for the demanding work ahead in the fields.

However, many locals note that with the rise of urbanization and the shift to a more modern lifestyle, these agricultural customs and festivals are becoming less common. The move towards urban living is gradually diminishing the traditional farming practices that have been an integral part of the region's culture.

Types of Farming

The diverse landscape of Sindhudurg comprises coastal plains, fertile valleys, and hilly terrains, which support a variety of crops, each cultivated using traditional and region-specific methods. Among the most prominent farming practices in Sindhudurg, rice cultivation holds a central place. The district’s rich agricultural history is reflected in the cultivation of rice, millets, and other crops, with farmers adapting their practices to the unique characteristics of the region’s land and climate.

Rice Farming

Rice has long been the dominant crop in Sindhudurg, occupying a significant portion of the district's tillable land. The region’s rice farming is known for its diversity, with unique techniques and varieties that reflect the traditional agricultural practices passed down through generations.

The traditional rice farming process, as outlined in the gazetteer, begins with the arrival of the monsoon in June. Fields with high moisture retention are plowed after the first few showers, preparing the soil for sowing. As the rain intensifies, the rice plants begin to grow rapidly. After about a month, when the soil softens, the plants are uprooted in bunches and transplanted into pre-prepared fields, spaced about 8-10 inches apart. In some villages, however, rice is first grown in nurseries, and once the seedlings are strong enough, they are transported to fields, which may be located several kilometers away. This practice is believed to help control the growth of young plants more effectively while also protecting them from weeds and pests early in the season.

Throughout the growing season, fields are regularly weeded to ensure healthy growth. By October or November, the rice reaches maturity and is ready for harvest. After harvesting, the rice is spread out to dry under the sun. The grain goes through various stages during its growth, each marked by a local name: bi (seed), rov (early green shoots), tarva (ready for transplanting), posavle (seed pods forming), dudhgile (milky seed consistency), and bhat (mature, ready for harvesting).

Once harvested, the rice is tied into sheaves and left for about a month before being thrashed by beating the sheaves against a well-cleaned threshing floor. The grain is then winnowed to remove the husks. In fields where the soil can support a second crop, land is prepared again in November. Interestingly, this second crop, according to the gazetteer, does not require additional manuring or soil-breaking after plowing, which probably helps farmers maximize land use without incurring additional costs.

In Sindhudurg, rice farming also involves a distinctive method called Lavan, Lavani, or Roplavani, terms used interchangeably by locals. This method is believed to be particularly practiced in the Konkan region, where rice is grown on small fields that retain water for long periods. The seeds are first sown in these fields and allowed to grow for about 21 days before being transplanted into fields prepared with rainwater.

Locals say that this method is well-suited to the region's soil, which holds water for extended periods but can become sticky and difficult to manage. The Lavan technique is also said to help in reducing the growth of unwanted weeds, ensuring that the main crop flourishes without competition.

The region is home to a wide variety of rice, with thirty different types recorded in the Gazetteer. These include high-quality varieties like Kothambire (fragrant rice), Khirsal (fine-grained rice), and Gajvel (premium quality), as well as more common varieties such as Avchite and Kalinavan. The grain quality varies, with finer varieties like Surai (fine rice) not requiring pre-treatment before threshing, while coarser varieties like Ukde (rougher variety) require boiling and drying before processing. However, many locals note that the cultivation of these traditional varieties is slowly fading, raising concerns about the preservation of this rich agricultural heritage.

Nagli Cultivation

Nagli, also known as ragi, nachni, or finger millet, has historically been an essential crop in Sindhudurg, with locals noting that it once formed a significant part of the diet and provided sustenance for many families. Despite facing challenges in modern farming, Nagli remains an important crop, particularly in the district’s remote areas, where other crops may struggle to thrive. However, there is a growing concern among locals that the practice of cultivating nagli is slowly fading, as younger generations turn to more commercially viable crops.

According to the gazetteer, nagli was once widely cultivated, occupying a significant portion of the tillable land in the region. Although the practice continues in some parts of Sindhudurg, especially on the hilly slopes, many say that it is no longer as widespread as it once was. Yet, the region continues to maintain traditional farming methods unique to nagli cultivation, methods that have been passed down through generations and are still likely practiced today, particularly in the hilly areas where the crop thrives.

The traditional process of cultivating nagli, as described in the gazetteer, begins in April, when farmers clear the land by cutting down trees. These trees are then used as organic manure, enriching the soil. By May, the branches are burned, and the warm ashes provide the necessary nutrients for sowing nagli seeds. Farmers return in June, July, and September for weeding and to manage new shoots from the stumps of the felled trees. The harvest is typically ready in November after the rice crop has been gathered.

This labor-intensive process, known colloquially as dongar todna (hill breaking), is crucial for farmers in the hilly areas of Sindhudurg. It requires significant physical effort, with the burning of tree branches, soil preparation, and ongoing crop management throughout the season. However, it is also a practice that has sustained communities for generations, allowing them to cultivate a hardy crop on the challenging hillsides.

In addition to dongar todna, nagli is sometimes cultivated on the plains during the fair season using the bhava method. While this simpler approach is said to result in smaller yields compared to hill cultivation, it demonstrates Nagli's adaptability to various terrains and seasons.

For years, the crop has remained vital for food security in Sindhudurg. For many farmers in remote areas, nagli continues to be a reliable food source, especially in regions where other crops may struggle to grow. As farming practices evolve, Nagli’s role as a resilient, adaptable crop highlights its enduring value in sustaining local livelihoods and contributing to the district’s agricultural diversity.

Traditional Agricultural Practices

Every region has its distinct practices, passed down through generations, becoming an integral part of daily life. In Sindhudurg, farming is not just an occupation; it's a family tradition, a way of life that shapes the culture. The intimate practices tied to farming reveal the deep connection between the land and its people, turning farms into more than just fields as they become personal spaces, nurtured with care.

Nearly every farm in Sindhudurg is marked by a gate, a simple yet meaningful feature that not only protects the farm but also signifies ownership and pride. One of the unique practices that can be seen within the farmlands of the district is gavatachi tanas. After the paddy harvest, the remaining grass is carefully piled and stored to be used as fodder for cattle during the rainy season. Even with the onset of the monsoon, the grass remains fresh and usable, a testament to the farmers' meticulous care in preserving it.

Fascinatingly, the tradition of gavatachi tanas is deeply rooted in the agricultural cycle of the region. In the Konkan region, the monsoon typically begins in June, signaling the start of rice sowing. According to locals, when the Mrig Nakshatra begins around June 7, farmers begin plowing the land and sowing rice seeds, a process known as perani. Within 15 to 20 days, the seeds sprout into small plants, which are then uprooted and transplanted about 7 to 8 inches apart in plowed fields, a process referred to as lavni.

Farmers say that the rice plants grow for about 130 to 150 days before they are ready for harvest. Once harvested, the rice, called pendi, is beaten on the ground to separate the grains in a process known as zodani or malani. After threshing, the grains are left to dry in the sun, and once fully dried, the bundles are stacked in a specific pattern, called tanus, kudi, or ganji. According to locals, this stacking method is crucial to protect the inner layers of grass from the sun and rain, ensuring it remains intact and usable as fodder.

This connection to the land, however, extends beyond just the fields. In Sindhudurg, it is said that nearly every household has a designated space for growing vegetables, known as baugs.

These baugs are not only a means of cultivating a variety of fruits and plants that thrive in the region’s unique climate and soil, but also an important aspect of daily life. The vegetables grown here are primarily for direct consumption and form a key part of the area’s food culture, reflecting a long-standing tradition of using fresh produce in everyday cooking.

Use of Technology

The history of farming technology has evolved alongside agricultural practices, starting from basic tools and moving towards the advanced machinery seen today. Early farming relied heavily on manual labor and simple, hand-operated tools like hoes, sickles, and plows, traditionally made from wood or iron. These implements were essential for early agrarian societies, helping with tasks such as tilling the soil, planting, and harvesting. Over time, technological advancements began replacing these traditional tools, with the promise of greater productivity and efficiency.

Despite the introduction of new ones, when it comes to implements, they have not fully been replaced. In Sindhudurg, a blend of old and new technologies is still evident in agricultural practices. Traditional wooden instruments like kuri (a type of plow) and shevga (a hand-held tool for threshing) continue to be used in some areas of the district.

However, in response to changing times and the increasing demand for higher productivity, modern technology has also increasingly become a part of farming life. Mechanized tools and machinery are now commonly used for various agricultural tasks, ranging from tilling and planting to harvesting. This shift is also a reflection of the labor shortage caused by migration, with fewer people available to work on farms.

Both the use of traditional tools and the adoption of modern machinery highlight the adaptability and creativity of farmers, showcasing how agriculture in Sindhudurg continues to evolve while still maintaining a connection to its historical roots.

Market Structure: APMC

According to the Maharashtra State Agricultural Board website, Sindhudurg district is home to one APMC market, which offers a range of products including unhusked paddy, mangoes, cashew nuts, fish, and bamboo.

List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

|

Name |

Est. Year |

Chairman |

|

Sindhudurg |

1985 |

Tulshidas Tukaram Ravrane |

Locals point out that while Sindhudurg district does have some commercial agricultural activity, particularly with crops like mangoes, coconuts, and cashews being viewed as cash crops, farming is mainly focused on meeting the needs of local households. As a result, the district’s involvement with APMCs is relatively limited compared to other parts of Maharashtra.

Farmers Issues

In Sindhudurg, awareness of government schemes, as many say, is often disseminated through informal, community-based channels. The region's strong sense of community and cooperative spirit facilitates the exchange of information, with residents regularly discussing government initiatives among themselves, whether in urban centers or remote villages. News about available schemes typically spreads via word of mouth, with family members, friends, and neighbors playing a key role in passing along details.

Interestingly, in some rare cases, especially in remote areas, many point out that locals still rely on traditional methods of communication, such as Davandi. This involves a designated person walking through the village, using a tool to make a loud noise, and announcing important information to the public. This method, though less common today, reflects the community's reliance on local networks to stay informed.

Graphs

Irrigation

Cropping Metrics

Land Use and Credit

Sources

Gazetteers Department. 1880. District Gazetteers, Ratnagiri - Savantwadi District. Agriculture, Caste, Rainfall, and Soils. Government of Maharashtra.https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015…

NABARD. 2023-24. Potential Linked Credit Plan: Sindhudurg. Maharashtra Regional Office, Pune.https://www.nabard.org/auth/writereaddata/te…

S.S.P. MISHRA for MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD. 2014. Ground Water Information. Govt. of India.https://www.cgwb.gov.in/old_website/District…

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.