Contents

- Healthcare Infrastructure

- Medical Education & Research

- Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences

- Age-Old Practices & Remedies

- NGOS & Initiatives

- History of Major Disease Epidemics & Outbreaks in Wardha

- Graphs

- Healthcare Facilities and Services

- A. Public and Govt-Aided Medical Facilities

- B. Private Healthcare Facilities

- C. Approved vs Working Anganwadi

- D. Anganwadi Building Types

- E. Anganwadi Workers

- F. Patients in In-Patients Department

- G. Patients in Outpatients Department

- H. Outpatient-to-Inpatient Ratio

- I. Patients Treated in Public Facilities

- J. Operations Conducted

- K. Hysterectomies Performed

- L. Share of Households with Access to Health Amenities

- Morbidity and Mortality

- A. Reported Deaths

- B. Cause of Death

- C. Reported Child and Infant Deaths

- D. Reported Infant Deaths

- E. Select Causes of Infant Death

- F. Number of Children Diseased

- G. Population with High Blood Sugar

- H. Population with Very High Blood Sugar

- I. Population with Mildly Elevated Blood Pressure

- J. Population with Moderately or Severely High Hypertension

- K. Women Examined for Cancer

- L. Alcohol and Tobacco Consumption

- Maternal and Newborn Health

- A. Reported Deliveries

- B. Institutional Births: Public vs Private

- C. Home Births: Skilled vs Non-Skilled Attendants

- D. Live Birth Rate

- E. Still Birth Rate

- F. Maternal Deaths

- G. Registered Births

- H. C-section Deliveries: Public vs Private

- I. Institutional Deliveries through C-Section

- J. Deliveries through C-Section: Public vs Private Facilities

- K. Reported Abortions

- L. Medical Terminations of Pregnancy: Public vs Private

- M. MTPs in Public Institutions before and after 12 Weeks

- N. Average Out of Pocket Expenditure per Delivery in Public Health Facilities

- O. Registrations for Antenatal Care

- P. Antenatal Care Registrations Done in First Trimester

- Q. Iron Folic Acid Consumption Among Pregnant Women

- R. Access to Postnatal Care from Health Personnel Within 2 Days of Delivery

- S. Children Breastfed within One Hour of Birth

- T. Children (6-23 months) Receiving an Adequate Diet

- U. Sex Ratio at Birth

- V. Births Registered with Civil Authority

- W. Institutional Deliveries through C-section

- X. C-section Deliveries: Public vs Private

- Family Planning

- A. Population Using Family Planning Methods

- B. Usage Rate of Select Family Planning Methods

- C. Sterilizations Conducted (Public vs Private Facilities)

- D. Vasectomies

- E. Tubectomies

- F. Contraceptives Distributed

- G. IUD Insertions: Public vs Private

- H. Female Sterilization Rate

- I. Women’s Unmet Need for Family Planning

- J. Fertile Couples in Family Welfare Programs

- K. Family Welfare Centers

- L. Progress of Family Welfare Programs

- Immunization

- A. Vaccinations under the Maternal and Childcare Program

- B. Infants Given the Oral Polio Vaccine

- C. Infants Given the Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG) Vaccine

- D. Infants Given Hepatitis Vaccine (Birth Dose)

- E. Infants Given the Pentavalent Vaccines

- F. Infants Given the Measles or Measles Rubella Vaccines

- G. Infants Given the Rotavirus Vaccines

- H. Fully Immunized Children

- I. Adverse Effects of Immunization

- J. Percentage of Children Fully Immunized

- K. Vaccination Rate (Children Aged 12 to 23 months)

- L. Children Primarily Vaccinated in (Public vs Private Health Facilities)

- Nutrition

- A. Children with Nutritional Deficits or Excess

- B. Population Overweight or Obese

- C. Population with Low BMI

- D. Prevalence of Anaemia

- E. Moderately Anaemic Women

- F. Women with Severe Anaemia being Treated at an Institution

- G. Malnourishment Among Infants in Anganwadis

- Sources

WARDHA

Health

Last updated on 26 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Wardha’s healthcare landscape, like many other regions across India, is shaped by a mix of indigenous and Western medical practices. For centuries, indigenous knowledge and treatments provided by practitioners such as hakims and vaidyas have formed the foundation of healthcare in the region. This long-standing relationship between communities and their natural environment played a key role in shaping the district’s early medical traditions. Over time, its landscape has gradually evolved with the introduction and expansion of more specialized medical services.

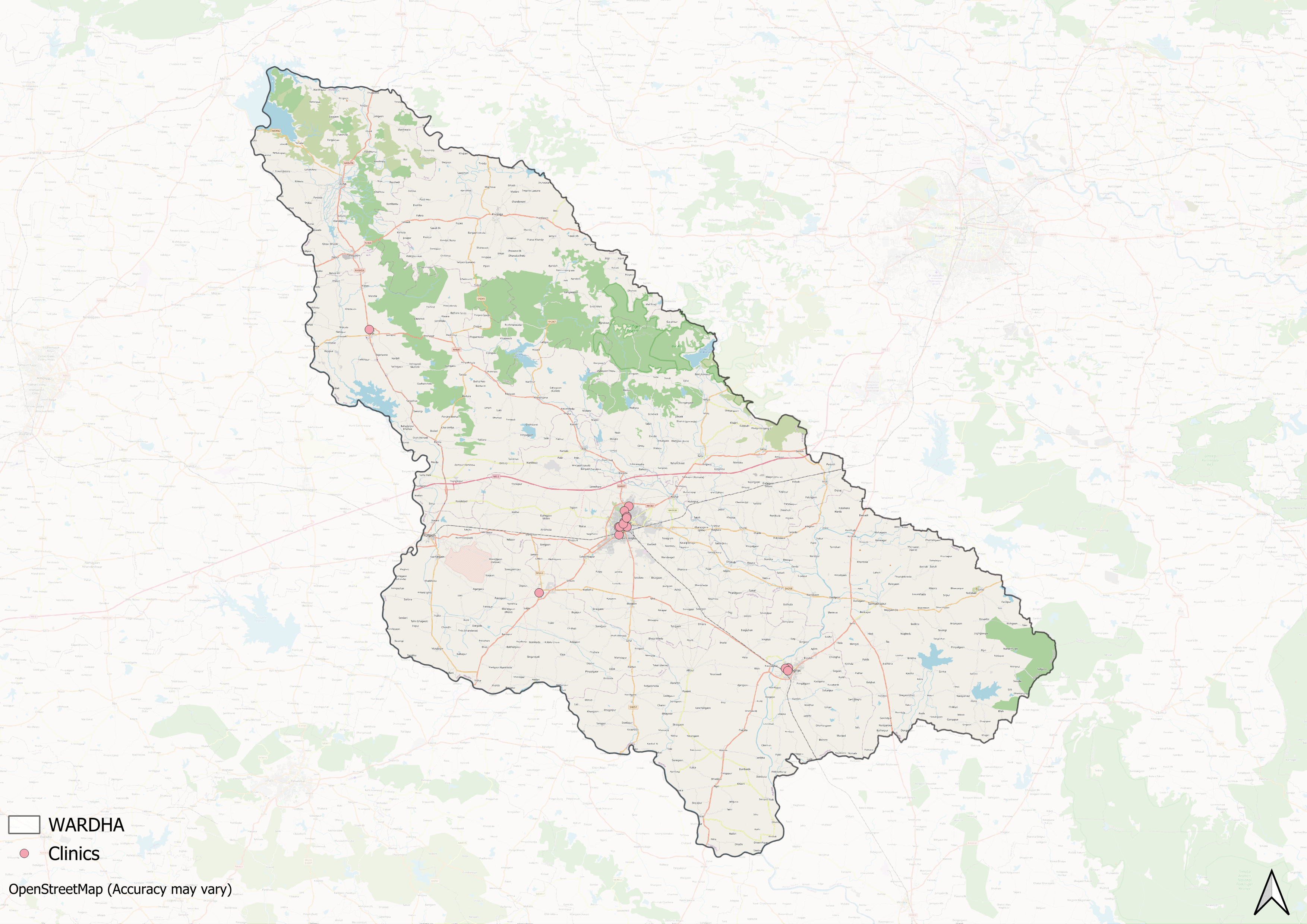

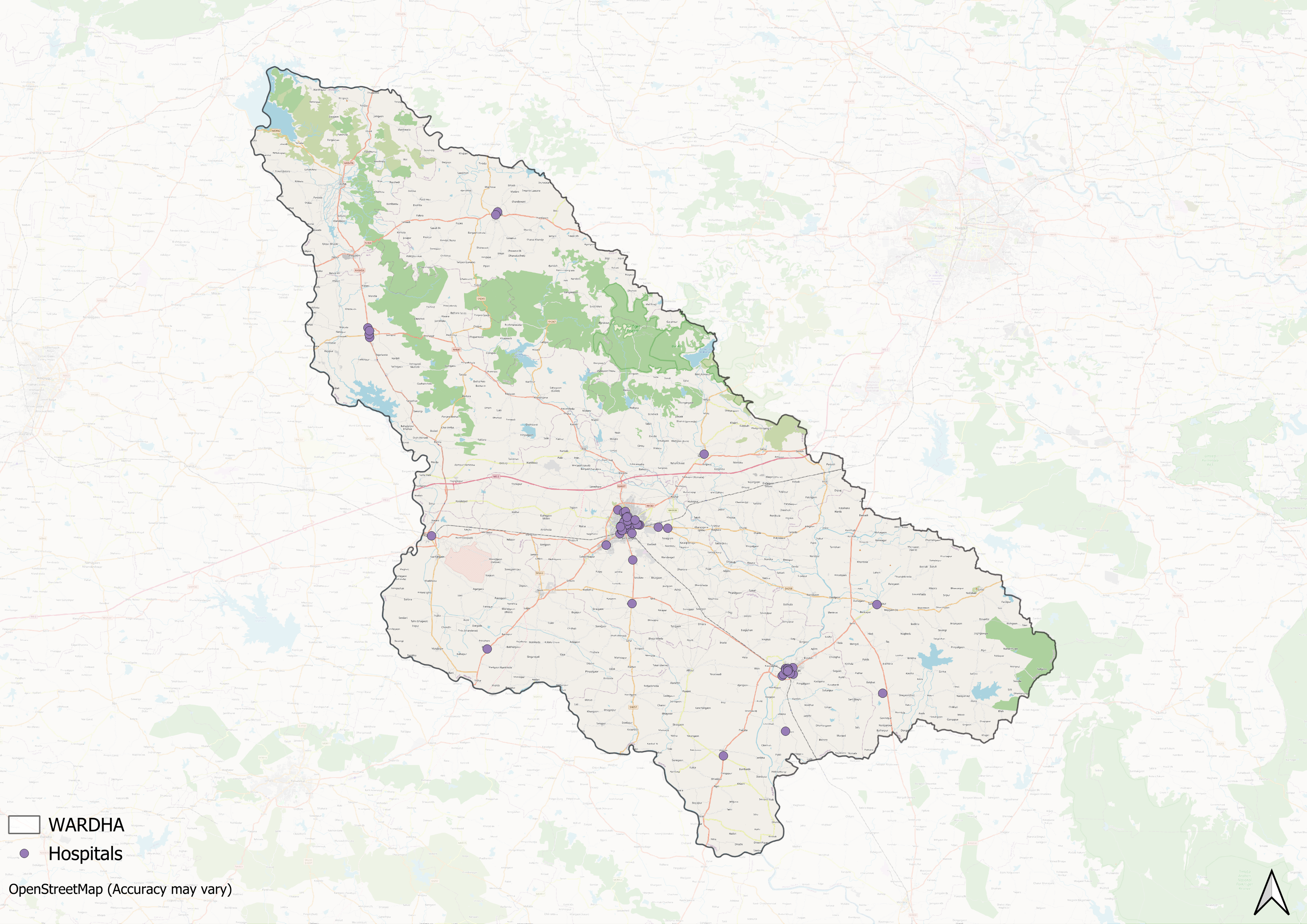

Healthcare Infrastructure

Much like other regions in India, Wardha’s healthcare infrastructure follows a multi-tiered system that involves both public and private sectors. Currently, the public healthcare system is tiered into primary, secondary, and tertiary levels. Primary care is provided through Sub Centres and Primary Health Centres (PHCs), while secondary care is managed by Community Health Centres (CHCs) and Sub-District hospitals. Tertiary care, the highest level, includes Medical Colleges and District Hospitals. This system has been shaped and refined over time, influenced by national healthcare reforms.

Supporting this structure is a network of Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) who, as described by the National Health Mission, serve as “an interface between the community and the public health system.” Over time, this multi-layered healthcare model has been continuously shaped and refined by national healthcare policies and reforms, to provide universal health coverage across regions.

Wardha’s formal healthcare infrastructure, like much of India, has its origins in the colonial era, which laid the groundwork for the system in place today. According to the district Gazetteer (1974), in 1906, the Wardha district had ten dispensaries, including Police and Mission hospitals. According to the district Gazetteer (1974), by 1906, the district had around ten dispensaries, which included facilities set up by the police administration and by Christian missionaries. Among these, the Scotch Free Church Hospital stood out with a capacity of 44 beds, providing care at a time when larger hospitals were uncommon in the region. A leper asylum in the district was also managed by a missionary who provided accommodation for about 20 people affected by leprosy

The arrival of Mahatma Gandhi at Sevagram in 1936 brought new impetus to the district’s social and medical endeavours. It was here, in 1938, that Dr. Sushila Nayar came to visit her brother, then serving as Gandhi’s secretary. Her brief sojourn lengthened as she remained to assist during a cholera outbreak, an experience that deepened her interest in community medicine and shaped her future role as a public health leader.

Dr. Nayar stayed at Sevagram for a year and after earning her medical degree, she returned back here in 1942 and took part in the Quit India Movement, for which she was imprisoned. In 1944, she founded a modest dispensary within the ashram precincts. This facility gradually developed into Kasturba Hospital, formally inaugurated in 1945, initially with a focus on maternity and child care. The hospital flourished under the stewardship of the ashram until 1954, when its management was entrusted to Gandhi Smarak Nidhi.

![Kasturba Hospital[1]](/media/statistic/images/maharashtra/wardha/health/kasturba-hospital1-ee6c1200.png)

Following Gandhi’s death, Dr. Nayar proceeded to the United States for higher studies in public health. On her return, she established a tuberculosis sanatorium in Faridabad (Haryana) and subsequently served as Health Minister for Delhi. Her work strengthened her conviction that rural India must have access to well-trained medical practitioners.

Over the years, Wardha’s healthcare system has expanded through both public and private initiatives. While the public health infrastructure has grown steadily, the late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen the rise of private hospitals across the district. Many of these facilities have been established by local trusts, non-governmental organisations, and community groups, aiming to improve access to medical care in rural and semi-urban areas.

Among the prominent private facilities is the Acharya Vinoba Bhave Rural Hospital, which provides a range of specialised services, including departments for neurology, dermatology, and psychiatry.

Medical Education & Research

Medical education and research play a crucial role in strengthening a district’s overall healthcare system. Well-functioning medical institutions not only train the next generation of doctors, nurses, and health workers but also directly contribute to providing medical services to the local community. As Mathew Gerge (2023) points out, this ‘dual purpose’ means that a medical college or research centre can help meet both the need for skilled professionals and the immediate healthcare needs of the population it serves. In Wardha district, this approach is reflected in the presence of both private institutions and government-aided colleges, which together form the backbone of the region’s medical education network.

Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences

The Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences (MGIMS) was established in Sevagram in 1969 as part of the Gandhi Centenary Programme. The institute was created to bridge the gap in rural healthcare by producing medical graduates who would serve in non-urban areas. Today, MGIMS provides a range of medical services, including departments in neurology, dermatology, and psychiatry. The institute remains known for its focus on affordable treatment. In 2020, The Times of India (2020) reported that the hospital charged only ₹1,000 per day for an ICU bed, with other costs for tests, medicines, and consumables kept significantly lower than in most private hospitals.

Age-Old Practices & Remedies

Historically, before the advent of Western health care systems or the three-tiered healthcare infrastructure that exists today, people in the district relied on and made use of indigenous knowledge and medicine for their well-being. When it comes to healthcare, India, for long, has been characterized by a pluralistic health tradition.

When considering traditional knowledge and systems of medicine, Mahatma Gandhi's influence is undeniable, especially in Wardha, where he spent significant time. Mahatma Gandhi’s time at Sevagram Ashram had a significant impact on how local communities understood and practised health and healing. Deeply influenced by nature-cure principles, Gandhi promoted the use of simple, natural treatments, fasting, and a disciplined diet to prevent and treat disease. He often applied these ideas to care for individuals affected by conditions that carried heavy social stigma, such as leprosy.

One of the most documented instances of Gandhi’s hands-on care in Wardha is his close work with Parchure Shastri, a Sanskrit scholar suffering from leprosy. At a time when leprosy patients were often socially isolated, Gandhi personally nursed Shastri at Sevagram, tending to his wounds and setting an example of compassion-driven care that challenged widespread fear and neglect.

![Gandhi personally tended to Parchure Shastri at Sevagram Ashram, demonstrating care for leprosy patients at a time of widespread stigma.[2]](/media/statistic/images/maharashtra/wardha/health/gandhi-personally-tended-to-parchure-shastri-_sg2QQ9u.png)

In his daily practice, Kant and Bhargav (2019) note that Gandhi relied on a small set of easily available remedies, castor oil, sodium bicarbonate, iodine, and dietary changes, combined with a firm belief in the healing power of nature and personal discipline. This approach left a lasting imprint on how leprosy and other diseases were addressed in the area, blending medical care with community dignity.

Wardha district’s rural areas have also long preserved ethnomedicinal practices through local healers. In forested parts of Karanja (Ghadge) taluka, knowledge of native plants for treating various conditions — including bites and fevers — continues to be passed down orally. Plants like Aghada (Achyranthes aspera Linn.) are still used today, prepared as kadha or pastes for treating bites from scorpions, dogs, or snakes.

![Aghada[3]](/media/statistic/images/maharashtra/wardha/health/aghada3-0e01447b.png)

NGOS & Initiatives

The determinants of health and health outcomes, as the World Health Organization (WHO) elaborates, are not solely shaped by more than just medical factors and healthcare services. The organization uses the term “social determinants of health (SDH)” to refer to the “non-medical factors that influence health outcomes.” These non-medical factors can be sanitation, nutrition, community well-being, or, as the WHO outlines, “income and social protection,” “food security,” access to quality healthcare, and more.

While there have been ongoing efforts to strengthen Wardha district’s healthcare infrastructure, certain areas still face challenges, particularly in addressing these broader health determinants. In response, non-governmental organizations have emerged as vital partners, working alongside public health systems to develop innovative, grassroots-level approaches that bridge these gaps.

National Organisation for Community Welfare

Anemia is a persistent public health concern in several tribal-dominated regions of Maharashtra, including Wardha district. High rates of low hemoglobin (Hb) levels have been documented among women and children, often indicating moderate to severe anemia.

To address this challenge, the National Organisation for Community Welfare, supported by the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India, launched a kitchen garden initiative in 2011. The project was implemented across five villages and aimed to improve household nutrition through small-scale vegetable cultivation.

![Kitchen garden plots cultivated by local families as part of the nutrition project in Wardha district.[4]](/media/statistic/images/maharashtra/wardha/health/kitchen-garden-plots-cultivated-by-local-fami_C0OVwiL.png)

A. Pallavi (2013) in her article reports that baseline study conducted at the start of the project tested 373 women across different age groups. Results showed that 60 to 90 percent of women in each village had Hb counts ranging from 7 to 9 g/dL.

A year later, follow-up tests conducted on 115 women showed remarkable improvements, with 113 women recording increases in their Hb counts. The number of women with a healthy Hb count of 11 and above increased dramatically from nine to 100. The kitchen garden programme, in many ways, remains an example of community-led efforts to improve dietary diversity and tackle anemia using locally available resources.

History of Major Disease Epidemics & Outbreaks in Wardha

In the 20th century, Wardha district experienced outbreaks of several infectious diseases, including cholera, smallpox, tuberculosis, and leprosy, as well as widespread cases of malaria, diarrhea, dysentery, pneumonia, and other digestive disorders. According to the district Gazetteer (1974), leprosy alone was found to affect between 2 and 2.5 percent of the population, marking the region as endemic for the disease.

During this period, Mahatma Gandhi’s Sevagram ashram housed a small clinic for leprosy care. The facility provided basic treatment and support for individuals affected by the disease, reflecting an early effort to address both medical needs and the social challenges linked to leprosy in the district.

Graphs

Healthcare Facilities and Services

Morbidity and Mortality

Maternal and Newborn Health

Family Planning

Immunization

Nutrition

Sources

Bhalavi, R. B., & Bhoyar, R. A. 2021. "Ethno-Botanical Survey on Medicinal Plants Used by Tribes of Karanja Ghadge Tahsil, Wardha District, Maharashtra, India." ResearchGate.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350585548_Ethno-botanical_Survey_on_Medicinal_plants_used_by_Tribes_of_Karanja_Ghadge_Tahsil_of_Wardha_District_Maharashtra_Indiahttps://www.researchgate.net/publication/350…

Dr. Anshu’s Blog. 2019. "Gandhi and Leprosy." Dr. Anshu’s Blog.ttps://dranshublog.com/gandhi-and-leprosy/https://dranshublog.com/gandhi-and-leprosy/

E-Gov by Elets. "Wardha’s Effective Measures Against COVID-19: Vivek Bhimanwar Explains." E-Gov, Elets Online.https://egov.eletsonline.com/2020/07/wardhas-effective-measures-against-covid-explains-vivek-bhimanwar/https://egov.eletsonline.com/2020/07/wardhas…

Jaideep Hardikar and Chetana Borkar. 2020. "Vidarbha’s Pastoralists Paying a Pandemic Price." Rural India Online.https://ruralindiaonline.org/en/articles/vidarbhas-pastoralists-paying-a-pandemic-price/https://ruralindiaonline.org/en/articles/vid…

John, T. Jacob. 2023. "The Real Purpose of the Medical College." The Hindu.https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/the-real-purpose-of-the-medical-college/article67232008.ecehttps://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/the-r…

M Choksi, B. Patil et al. 2016.Health systems in India.Vol 36 (Suppl 3).Journal of Perinatology.https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5144115/https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC514…

Maharashtra State Gazetteers. 1977. Wardha District Gazetteer: Medical and Public Hospitals. Gazetteer Department, Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai.

Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences (MGIMS). "History and Heritage." MGIMS, Wardha.https://www.mgims.ac.in/index.php/about-us/history-and-heritagehttps://www.mgims.ac.in/index.php/about-us/h…

Nagarajan, Rema. 2020. "Hospital in Wardha Shows Quality Healthcare Can Be Affordable Too."TheTimes of India, India.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/hospital-in-wardha-shows-quality-healthcare-can-be-affordable-too/articleshow/79661350.cmshttps://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/ho…

National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). "Gandhi’s Influence on Public Health." NCBI.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6515724/#:~:text=Gandhiji%20was%20a%20firm%20believer,mind%20as%20he%20should%20havehttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PM…

Pallavi, Aparna. 2013. "Become an Iron Woman: Eat Veggies." Down to Earth, India.https://www.downtoearth.org.in/environment/become-iron-woman-eat-veggies-41035https://www.downtoearth.org.in/environment/b…

World Health Organization (WHO). "Social Determinants of Health." World Health Organization.https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-det…

Last updated on 26 July 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.